(Tunis) – The referral of a businessman to trial before a military court, and the incommunicado detention of seven other men in undisclosed locations, is a threat to human rights in Tunisia, Human Rights Watch said today.

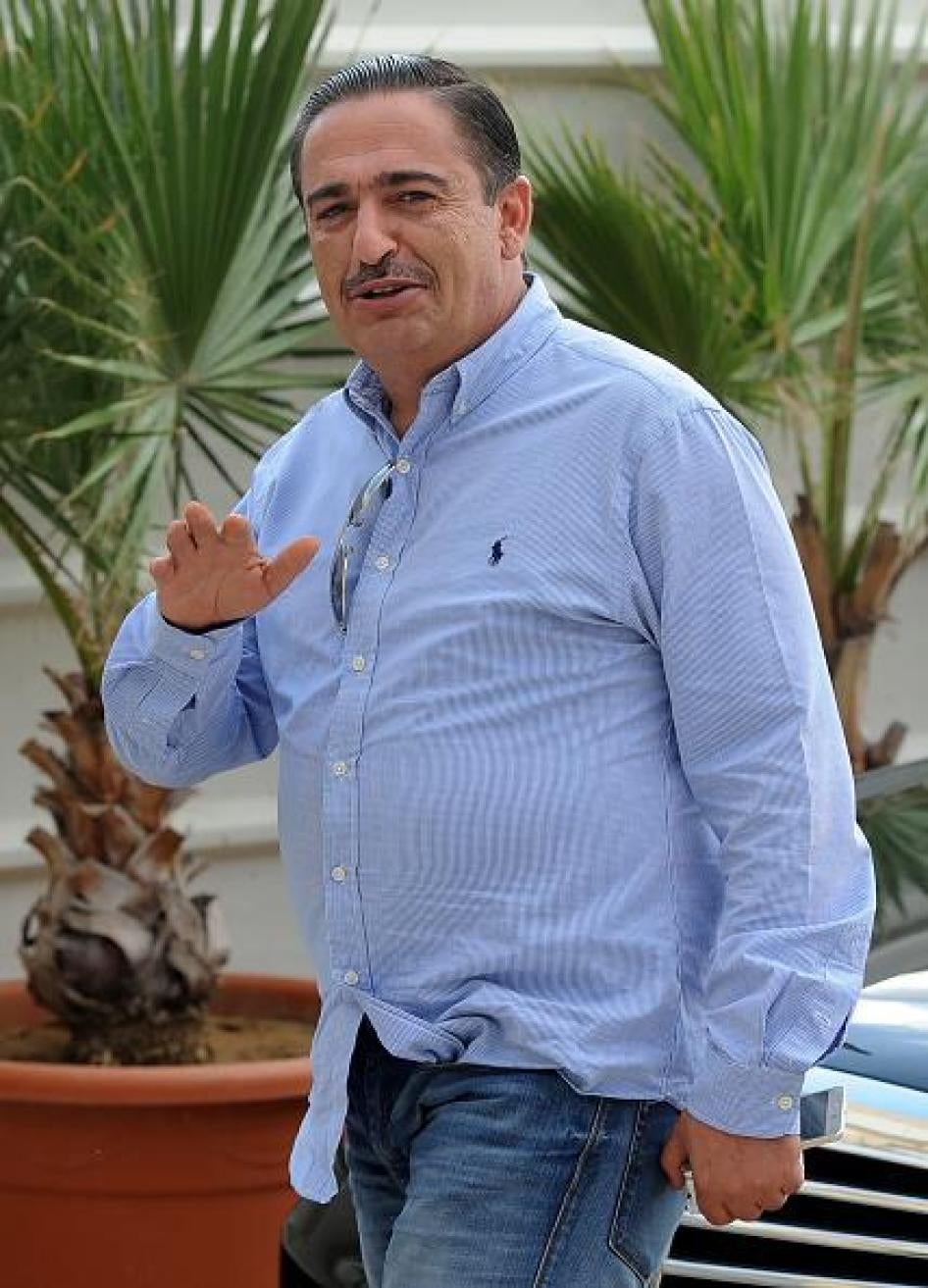

Authorities arrested Chafik Jarraya, a well-connected businessman, and seven other men, between May 23 and 25, 2017. They placed Jarraya and the others under “house arrest” in an unknown location, a procedure allowed under the country’s state of emergency. Authorities said the men were involved in corruption and represented a threat to state security.

“A genuine democratic transition has no place for military trials for civilians or secret detention, no matter how serious the charges,” said Amna Guellali, Tunisia director at Human Rights Watch. “Just as transparency and the rule of law are the best safeguards against corruption, they should also guide the fight against corruption, if that is indeed what these cases are about.”

On May 26, the military prosecutor’s office announced that he had indicted Jarraya on charges of treason and intelligence with a foreign army, punishable by the death penalty. His lawyers were able to visit him at the military barracks in Al Aouina. Authorities have not disclosed the whereabouts of the others or the charges against them.

Tunisian authorities have previously used house arrests under the state of emergency. They have also tried civilians before military tribunals, in most cases for defamation of the army as an institution and of specific officers. However, this appears to be the first time since the ouster of President Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali in 2011 that authorities have held people incommunicado, without access to lawyers, and without informing families of their whereabouts.

Under Tunisian and international law, all detainees have the right to be promptly informed of the charges against them, to contact their family and lawyer, and to have their detention reviewed by a judge. International law views house arrest as a form of detention that warrants basic safeguards that the government must respect even during a state of emergency.

On May 26, the Confiscation Commission, a state body created in 2011 to confiscate and freeze assets of the Ben Ali family and anyone who financially benefited from ill-gotten gains under the Ben Ali government, announced that it has frozen the assets of eight men: Jarraya, Yassine Channoufi, Mongi Ben Rbeh, Nejib Ben Ismaïl, Ali Karoui, Hlel Ben Massaoud Bchiri, Mondher Jnayah, and Kamel Fraj.

In an interview with La Presse newspaper, on June 6, 2017, Youssef Chahed, the head of government, said that the arrest of Jarraya and seven other men was linked to the fight against corruption. He did not name the seven others. Chahed also said that he had “presided over the preliminary investigations that had led to their arrests.” “This is not a one-off operation,” he said. “People should get used to it in the same way as the fight against terrorism.” He justified the use of the emergency law by saying “this is an exceptional situation and it requires exceptional measures. These people represent a threat to state security.”

On May 25, 2017, the Interior Ministry stated on its website that it had “place[d] under house arrest a number of people, based on information proving their involvement in acts threatening public security and order.” The ministry described the measures as preventive, limited in duration, and warranted by the need to protect security and fight corruption. The ministry asserted that it would respect the legal guarantees enshrined in the constitution and in the laws pertaining to people placed under house arrest, and would stop using this measure when the state of emergency was lifted.

Zouhair Chennoufi, the lawyer and brother of Yassine Chennoufi, and Imed Ben Hlima, the lawyer for Nejib Ben Smaïl, both businessmen, confirmed to Human Rights Watch that they have not been able to locate their clients since their arrest.

The authorities should promptly disclose the whereabouts of the detainees, ensure they can freely communicate with their lawyers, and ensure they and their lawyers have access to incriminating evidence against them. All the detainees should be brought promptly before a judge to review the legality and necessity of their detention.

Faiçal Jadlaoui, one of Jarraya’s lawyers, told Human Rights Watch that the military investigative judge overseeing this case has not allowed the lawyers to make photocopies of the case file, authorizing them only to read the documents in his office. He said the lawyers have refused to do so because they consider this refusal a breach of the rights of the defense. Jadlaoui said the lawyers were able to visit Jarraya at the military barracks in Al Aouina. He said authorities had not interrogated his client as of June 7.

President Béji Caid Essebsi declared a state of emergency on November 24, 2015, after a suicide bombing in Tunis. He has renewed it several times, most recently on May 16, 2017, for one month.

Tunisia’s state of emergency is based on a 1978 presidential decree that gives the Interior Ministry the authority to order the house arrest of anyone whose “activities are deemed to endanger security and public order.” The emergency decree does not stipulate that authorities must disclose the location of the house arrest.

Corruption, rife during the Ben Ali presidency, has continued since his ouster. Chawki Tabib, president of the National Anti-Corruption Authority, warned the problem had reached “epidemic” proportions. Chahed has vowed to fight corruption since becoming prime minister in 2016.

These arrests come after Imed Trabelsi, a nephew of Leila Trabelsi, Ben Ali’s wife, said in a live televised hearing on May 19, 2017, before the Truth and Dignity Commission, Tunisia’s independent body investigating past human rights violations, that he benefited from a system of corruption involving a wide network of businessmen, customs officers, and ministers.

Informed listeners inferred that the figures he was speaking about included Jarraya and Channoufi, although he did not name them.

If Tunisian authorities proceed with house arrests under the state of emergency, under international law they should do so only for finite periods of time, disclose the whereabouts of anyone detained this way, and allow them to meaningfully appeal their detention and to have access to judicial review.

Tunisian law grants broad jurisdiction to military courts over a variety of acts committed by civilians as well as military personnel.

Allowing the prosecution of a civilian before a military tribunal is a violation of the right to a fair trial and due process guarantees, Human Rights Watch said. International human rights experts have consistently determined that trials of civilians before military tribunals violate the due process guarantees in article 14 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which affirms that everyone has the right to be tried by a competent, independent, and impartial tribunal.

The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, interpreting the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, has prohibited the trial of civilians in military courts. The Resolution on the Right to a Fair Trial and Legal Aid in Africa, noted that “[t]he purpose of Military Courts is to determining offences of a pure military nature committed by pure military personnel.”