His Excellency Sabah Al-Khalid Al-Sabah

First Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs

Ministry of Foreign Affairs

Kuwait City

The State of Kuwait

Your Excellency,

I write to express our appreciation for your government’s engagement with Human Rights Watch and to seek further clarification about recent laws and regulations promoting the rights of domestic workers in Kuwait.

As you may know, Human Rights Watch monitors and advocates for greater protection of migrant domestic workers’ rights in countries around the world, including Kuwait. In 2010, we published a report on migrant domestic workers in Kuwait, “Walls at Every Turn.”[1] We also issued a press release in June 2015 welcoming the adoption of Law No. 68/2015 on Domestic Labor.[2]

We welcome the recent steps taken to promote domestic worker’s rights in Kuwait. However, we are concerned that Kuwait’s laws and regulations on domestic workers, while moving in the right direction, still fall short of what is needed to ensure domestic workers’ rights are protected. Our attached briefing identifies key gaps and offers suggestions for addressing them. If Kuwait brings its laws and practices into full alignment with the ILO Domestic Workers Convention and other key international standards, it would become a leader on migrant domestic worker rights for the Gulf region.

We are grateful to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs for sending us a copy of the implementing regulation on domestic workers, published in the Official Gazette in July 2016. We kindly request a copy of the standard contract for domestic workers as well as the official text of Ministerial Decree No. 2302/2016.

It would be most helpful if you could direct any response to my colleague, [Name Redacted], who can be reached by email at [Redacted] or on [Redacted] by October 14, 2016. Thank you for your consideration.

Yours sincerely,

Janet Walsh

Acting Director

Women’s Rights Division

Human Rights Watch analysis of Kuwait’s laws and regulations on domestic workers

This briefing assesses Kuwait’s laws and regulations on domestic workers and highlights certain aspects that fall short of what is needed to ensure protection of domestic workers’ rights. It outlines gaps in relation to Law No. 68 of 2015 on Domestic Labor Law (hereafter “domestic worker law”), Ministerial Decree No. 2194 of year 2016 regarding the Implementing Regulations of Law No. 68 of 2015 on Domestic Labor (hereafter “implementing regulations”), and Ministerial Decree No. 2302/2016 regarding implementation procedures of Law No. 68/2015 on Domestic Labor. It also discusses the kafala system.

We urge the Kuwaiti authorities to ratify the ILO Domestic Workers Convention; bringing Kuwaiti law into full alignment with the Domestic Workers Convention would remedy all of the key issues identified below. [3] In the meantime, we call on the authorities to reform and, in some cases, clarify laws, regulations, and policies to ensure that Kuwaiti law recognizes and protects domestic workers’ rights, and that domestic workers are treated equally to other workers under the labor law. Kuwait voted in favor of the adoption of the ILO Domestic Workers Convention, which sets the international standard on treatment of domestic workers. The Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, which oversees the Convention of the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women to which Kuwait is a state party, has also called on state parties to ratify the ILO Domestic Workers Convention.

- Domestic worker law and implementing regulations

We welcome the adoption of the 2015 domestic worker law, which provides for domestic workers to have a weekly day off, 30 days of annual paid leave, a 12-hour working day with rest, and an end-of-service benefit of one month of pay per year of service at the end of the contract, among other rights.[4] We also welcome the further protections for domestic workers provided under the implementing regulations published in July 2016.[5] However, several key gaps remain.

- Equal treatment between domestic workers and other workers

Domestic workers and workers should be treated on an equal footing with other workers in relation to normal hours of work, overtime compensation, periods of daily and weekly rest and paid annual leave. [6] Yet Kuwait’s domestic worker law provides for a maximum 12-hour working day with unspecified “hours of rest” and one day off a week. In contrast, Kuwait’s 2010 labor law (Law No. 6 Governing Labor in the Private Sector) provides that workers in other sectors are guaranteed a 48-hour work week, or eight hours a day, and an hour of rest after every five hours of work.[7]

The implementing regulations clarify that employers must pay overtime compensation to domestic workers and that overtime should not exceed more than two hours per day, for which the worker should receive half a day’s salary in return. [8] However, the law does not require the worker’s consent to work overtime. In comparison, the labor law provisions for workers in other sectors provide that employers may only require workers to work overtime in exceptional situations and with a written order. The labor law also limits overtime to two hours a day, but further curbs overtime to a maximum of 180 hours a year, three days a week or 90 days a year. The labor law provisions also clarify that “the worker shall have the right to prove by any means that the employer required him to perform additional works for an additional period of time.”[9]

Additionally, the domestic worker law requires employers to provide medical treatment but not paid sick leave.[10] In contrast, the labor law provides workers in other sectors with sick leave, starting at a minimum of 15 days at full pay.[11]

Domestic workers should also have the right to form a union and to collective bargaining, on an equal footing with other workers. [12] But Kuwait’s domestic worker law does not guarantee this right, while the labor law guarantees workers in other sectors the right to unionize—albeit to a limited extent for non-Kuwaitis.[13]

- Possession of identity documents

Domestic workers should be entitled to retain possession of their travel and identity documents; this is a key safeguard in preventing abuse and coercion by employers.[14]

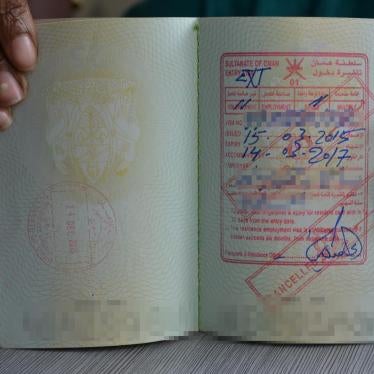

The Kuwait domestic worker law took the positive step of prohibiting employers from confiscating domestic workers’ passports.[15] However, the domestic worker law fails to specify penalties for passport confiscation. Moreover, the law allows employers to retain passports with a domestic worker’s consent, but does not clarify further (e.g., require written proof of consent). As domestic workers’ legal status is tied to their employers, it is unlikely that they will feel free to protest when employers or recruiting agents confiscate their passports. This could potentially be construed as consent by Kuwaiti authorities.

- Rest periods and paid leave

Domestic workers should be free to leave the household during rest and leave periods.

Although the domestic worker law provides for daily rest, a weekly rest day, and paid annual leave, it does not explicitly state that workers may leave the household during this time.[16] Moreover, the provision on a weekly rest day is not defined clearly to mean 24 consecutive hours.[17]

The Domestic Workers Convention also provides, importantly, that “periods during which domestic workers are not free to dispose of their time as they please and remain at the disposal of the household in order to respond to possible calls shall be regarded as hours of work.” Kuwait’s domestic worker law does not address this issue.[18]

- Food and accommodation

While Kuwait’s domestic worker law requires the employer to provide food and decent and adequate housing, it does not clarify what is meant by “decent and adequate.”[19]

The ILO Domestic Workers Recommendation (No. 201), which provides further guidance accompanying the Domestic Workers Convention, recommends that accommodation and food should include “(a) a separate, private room that is suitably furnished, adequately ventilated and equipped with a lock, the key to which should be provided to the domestic worker; (b) access to suitable sanitary facilities, shared or private; (c) adequate lighting and, as appropriate, heating and air conditioning in keeping with prevailing conditions within the household; and (d) meals of good quality and sufficient quantity, adapted to the extent reasonable to the cultural and religious requirements, if any, of the domestic worker concerned.”[20]

- Enforcement of contract rights; protections for workers lacking contracts

In Kuwait, the domestic worker law says that certain rights should be included in “contracts prepared by the Domestic Workers’ Department.” Several of these rights appear only in article 22 concerning contracts, and nowhere else in the law. For example, the right to a maximum of 12 working hours with rest breaks and the rights to a weekly rest day and paid annual leave appear only in the contract article, not elsewhere in the law.[21]

This raises a concern about enforceability of contractual rights, and what happens to workers who lack contracts or have older contracts that do not reflect these new rights.[22] The domestic worker law prohibits employers from using a different contract to the standard contract issued by the department, and sanctions agencies that use a different contract. But for those workers that lack an up-to-date contract with these protections, it is not clear if a court or other Kuwaiti authorities would consider these rights legally binding and thus obligatory on employers and enforceable absent a contract.[23]

- Wage discrimination

Kuwaiti law should ensure that domestic workers enjoy minimum wage coverage, and that compensation does not discriminate based on sex, race or national origin.[24] Kuwait has ratified human rights treaties, including the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, which obligate it to eliminate discrimination on the basis of national origin and race.[25]

Kuwait’s domestic worker law states that wages for domestic workers must not be less than the minimum wage set by the Ministry of Interior.[26] Human Rights Watch understands that a ministerial decree established a minimum wage for domestic workers of KD60 (US$200) per month.[27] According to media reports, this is the same as the minimum wage set in 2010 for other workers under the labor law.[28]

This is an important step forward. However, there is a remaining issue of wage differentials based on nationality, which contributes to wage differences related to race and ethnicity. Several countries of origin have set monthly minimum salaries for their domestic workers. The salaries vary by country, ranging between KD70 (US$230) to KD120 ($400). Recruitment agencies, in turn, advertise domestic workers’ salaries on the basis of nationality, rather than on experience or skills. We are not aware of government efforts to remedy such nationality-based wage differences. This practice of setting salaries on the basis of nationality amounts to discrimination. It is unjustified, unequal treatment with no legitimate aim.

- Language of standard contract

Kuwaiti law should ensure that domestic workers are informed of their terms and conditions of employment in an appropriate, verifiable, and easily understandable manner, preferably through written contracts.[29] Kuwait’s domestic worker law requires there be a standard contract between the employer and the domestic worker, but only requires that the contract be available in Arabic and English and not in the worker’s language.[30]

- Enforcement mechanisms

Domestic workers should have effective access to courts, tribunals, or other dispute resolution mechanisms, and to complaint mechanisms under conditions that are not less favorable than those available to workers generally.[31]

The Domestic Labor Directorate in the Ministry of Interior has the authority to resolve disputes between domestic workers and employers, but does not appear to require employer participation in dispute resolution processes.[32] The department can sanction a recruitment agency, but not an employer, for failing to contact the department after being summoned.[33]

The law states that failure to reach a settlement means the case can be referred to court, but sets no timeline for conclusion of the department’s grievance procedure.[34] While a court date should be set within a month of the department referring the case, the does not set out a timeline for the court to decide on such disputes.[35] This could deter domestic workers from pursuing a remedy, especially those who have left employment and can no longer legally work.

The law and implementing regulations set out some sanctions for employers, such as for delayed wages and not paying overtime compensation.[36] The Ministry of Interior’s domestic workers directorate can also temporarily suspend visa issuance for more domestic workers when a complaint against an employer is proven.[37] However, the law does not specify sanctions against employers who fail to provide adequate housing, food, and medical expenses, daily breaks, or weekly rest days.

Furthermore, the law provides that upon the settlement of any dispute or grievance between the domestic worker and the employer, the Domestic Workers’ Directorate will issue the domestic worker a document stating that the worker has no “pending claims” against their employer and recruitment agency.[38] Such a document should verify only that the specific claim was resolved, but not preclude future claims, including claims on other issues that may be based on factual circumstances existing at or before the time of settlement.

- Inspections

Kuwait should carry out robust and effective labor inspections for domestic workers.[39]

Kuwait’s domestic worker law provides for inspection of recruitment offices by the Ministry of Interior. [40] However, it is not clear if the Ministry of Interior will coordinate with the Ministry of Social Affairs and Labor—which is responsible for labor inspections—in doing so. Moreover, the law says nothing about labor inspections of working conditions in households, which can be done with due regard to privacy.[41]

- Shelters

Human Rights Watch has called on Kuwait and other countries that host large numbers of migrant domestic workers to establish networks of emergency housing for domestic workers who need them, along with other protection measures.[42]

Kuwait took a positive step in December 2014 when it established a shelter for domestic workers fleeing abuse, with a capacity of 700 beds. But, according to media reports, the shelter does not allow women to freely leave the shelter unaccompanied and does not accept pregnant domestic workers.[43]

- Kafala system

In Kuwait, migrant domestic workers’ legal status is still tied to their employers, who act as their visa sponsors. Workers cannot transfer to another employer without their current employer’s consent. If they do, they are considered to have “absconded,” and can be arbitrarily detained, fined, or sentenced to imprisonment. Human Rights Watch has documented how this policy traps many domestic workers in abusive situations, and can end up punishing victims of employer abuse.[44]

On March 31, 2016, the Public Authority for Manpower published Administrative Decision no. 378/2016, which allows migrant workers (though not domestic workers) in the private sector to transfer their sponsorship to a new employer without their current employer’s consent after three years of work, provided they give 90-day notice to their current employers.[45] While this is a slight improvement, workers are still tied to employers for three years, and it does not apply to domestic workers.

We are concerned that the new 2015 domestic worker law reinforces the kafala system. It requires that the Ministry of Interior deport the “absconding” worker, with their travel expenses paid for by either the employer currently “harboring” the worker or the recruitment agency.[46]

[3] ILO Convention No. 189 concerning Decent Work for Domestic Workers (Domestic Workers Convention), adopted June 16, 2011, entered into force on September 5, 2013, http://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::p12100_instrument_id:2551460 (accessed September 16, 2016).

[4] Law No. 68 of 2015 on Domestic Labor, passed by Parliament on June 24, 2015, and published in the Official Gazette on July 26, 2015, at http://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/docs/ELECTRONIC/101760/122760/F1581984342/k2.pdf (accessed September 16, 2016). See Human Rights Watch news release, “Kuwait: New Law a Breakthrough for Domestic Workers,” June 30, 2015, https://www.hrw.org/news/2015/06/30/kuwait-new-law-breakthrough-domestic-workers.

[5] Ministerial Decree No. 2194 of year 2016 regarding the Implementing Regulations of Law No. 68 of 2015 on Domestic Labor, published in the Official Gazette on July 17, 2016.

[6] The Domestic Workers Convention requires this of all states party. Art. 10, ILO Convention No. 189 concerning Decent Work for Domestic Workers (Domestic Workers Convention), adopted June 16, 2011, entered into force on September 5, 2013.

[7] Art.22, Law No. 68 of 2015 on Domestic Labor; arts. 64-65, Law no.6 of 2010 on Labor in the Private Sector;

[8] Art. 14, Ministerial Decree No. 2194 of year 2016 regarding the Implementing Regulations: “The employer can assign the domestic worker an additional workload equal to maximum two hours per day, and the worker earns the compensation equal to the payment of a half a day.”

[9] Art.66, Law no.6 of 2010 on Labor in the Private Sector.

[10] Art.9, Law No. 68 of 2015 on Domestic Labor.

[11] Art. 69, Law no.6 of 2010 on Labor in the Private Sector.

[12] The Domestic Workers Convention requires this of all states party. Art. 3(3), ILO Domestic Workers Convention.

[13] Arts. 98-110, Law no.6 of 2010 on Labor in the Private Sector.

[14] The Domestic Workers Convention requires that domestic workers be “entitled to keep in their possession their travel and identity documents.” Art. 9(c), ILO Domestic Workers Convention.

[15] Art.12, Law No. 68 of 2015 on Domestic Labor.

[16] Art. 9, ILO Domestic Workers Convention.

[17] Art. 10(2), ILO Domestic Workers Convention.

[18] Art. 10(3), ILO Domestic Workers Convention.

[19] Arts. 9 and 11, ILO Domestic Workers Convention.

[20] Art. 15-18, ILO Domestic Workers Recommendation, 2011 (No. 201), http://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=1000:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:R201 (accessed September 16, 2016).

[21] Art.22, Law No. 68 of 2015 on Domestic Labor.

[22] The ILO Domestic Worker Convention also calls for “equal treatment between domestic workers” in accordance with laws and regulations regarding working hours, daily and weekly rest, and annual leave. Art. 10, Domestic Workers Convention.

[23] Art.18 and 24(e) of the Law No. 68 of 2015 on Domestic Labor.

[24] The ILO Convention requires that states party “ensure that domestic workers enjoy minimum wage coverage, where such coverage exists, and that remuneration is established without discrimination based on sex.” Art. 11, ILO Domestic Workers Convention.

[25] International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD), adopted December 21, 1965, G.A. Res. 2106 (XX), annex, 20 U.N. GAOR Supp. (No. 14) at 4, U.N. Doc. A/6014 (1966), 660 U.N.T.S. 195, entered into force January 4, 1969. Kuwait acceded to CERD on October 15, 1968.

[26] Art. 19, Law No. 68 of 2015 on Domestic Labor.

[27] Ministry of Interior, Ministerial Decree No. 2302/2016 regarding implementation procedures of Law No. 68/2015 on Domestic Labor.

[28] “Kuwait sets minimum wage for first time,” April 14, 2010, http://in.reuters.com/article/idINIndia-47693120100414 (accessed September 16, 2016).

[29] The Domestic Workers Convention requires this of all states party. Art. 7, ILO Domestic Workers Convention.

[30] Art.18, Law No. 68 of 2015 on Domestic Labor.

[31] The Domestic Workers Convention requires this of all states party. Art. 16, ILO Domestic Workers Convention.

[32] Art. 31, ILO Domestic Workers Convention.

[33] Art.24, Law No. 68 of 2015 on Domestic Labor.

[34] Arts. 31 and 35 of the Law No. 68 of 2015 on Domestic Labor.

[35] Art. 35 and 37 of the Law No. 68 of 2015 on Domestic Labor.

[36] Art.27 of the Law No. 68 of 2015 on Domestic Labor (delayed wages), and art. 19 of Ministerial Decree No. 2194 of year 2016 regarding the Implementing Regulations; see art. 28 of the Law No. 68 of 2015 on Domestic Labor, and art. 14 of Ministerial Decree No. 2194 of year 2016 regarding the Implementing Regulations (failure to pay overtime compensation).

[37] Art.20, Ministerial Decree No. 2194 of year 2016 regarding the Implementing Regulations.

[38] Art. 34 of the Law No. 68 of 2015 on Domestic Labor.

[39] Art. 17, Law No. 68 of 2015 on Domestic Labor.

[40] Art. 44 of the Law No. 68 of 2015 on Domestic Labor.

[41] Art. 24, ILO Domestic Workers Recommendation, 2011 (No. 201).

[42] The ILO Domestic Workers Recommendation (no. 201) calls on states party to the Domestic Workers Convention to take these measures as well. See art. 21 (c), ILO Domestic Workers Recommendation, 2011 (No. 201).

[43] “64 Indian female workers transferred to shelter in Kuwait,” Gulf News, January 12, 2015, http://gulfnews.com/news/gulf/kuwait/64-indian-female-workers-transferred-to-shelter-in-kuwait-1.1440104 (accessed September 16, 2016).

[44] For a full account of the kafala system see Human Rights Watch, “Walls at Every Turn,” pp.31-38.

[45] Kuwait News Agency (KUNA), March 31, 2016, “(Manpower): Transfer (work permit) after three years without return to employer,” http://www.kuna.net.kw/ArticleDetails.aspx?id=2495513&language=ar (accessed September 16, 2016).

[46] Art. 51, Law No. 68 of 2015 on Domestic Labor.