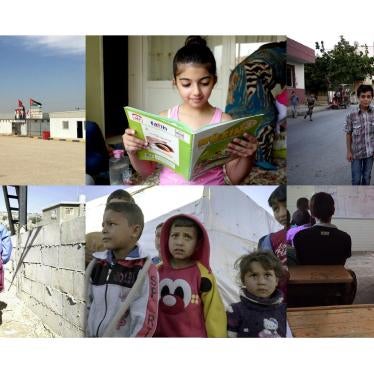

(Beirut) – More than half of the nearly 500,000 school-age Syrian children registered in Lebanon are not enrolled in formal education, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today. Although Lebanon, which is hosting 1.1 million registered Syrian refugees, has allowed Syrian children to enroll for free in public schools, limited resources and Lebanese policies on residency and work for Syrians are keeping children out of the classroom.

The 87-page report, “‘Growing Up Without an Education’: Barriers to Education for Syrian Refugee Children in Lebanon,” documents the important steps Lebanon has taken to allow Syrian children to access public schools. But Human Rights Watch found that some schools have not complied with enrollment policies, and that more donor support is needed for Syrian families and for Lebanon’s over-stretched public school system. Lebanon is also undermining its positive education policy by imposing harsh residency requirements that restrict refugees’ freedom of movement and exacerbate poverty, limiting parents’ ability to send their children to school and contributing to child labor. Secondary school-age children and children with disabilities face particularly difficult obstacles.

Despite Lebanon’s progress in enrolling Syrian children, the huge number of children still out of school is an immediate crisis, requiring bold reforms,” said Bassam Khawaja, Leonard H. Sandler fellow in the children’s rights division at Human Rights Watch. “Children should not have to sacrifice their education to seek safety from the horrors of war in Syria.”

Access to education is crucial to help refugee children cope with the trauma of war and displacement, and gain the skills to play a positive role in host countries like Lebanon and in the eventual reconstruction and future of Syria, Human Rights Watch said.

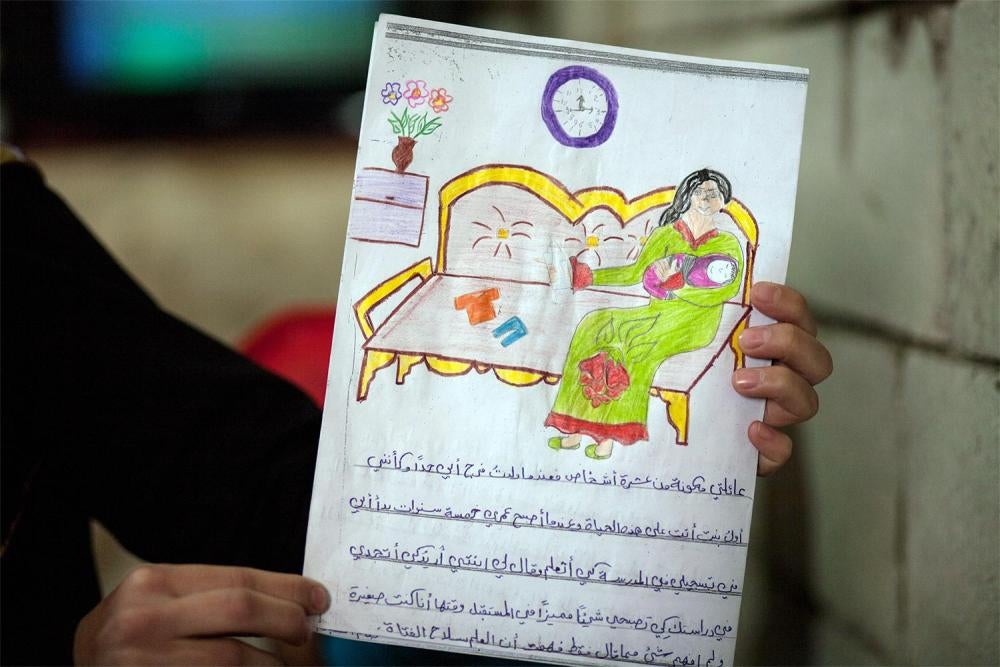

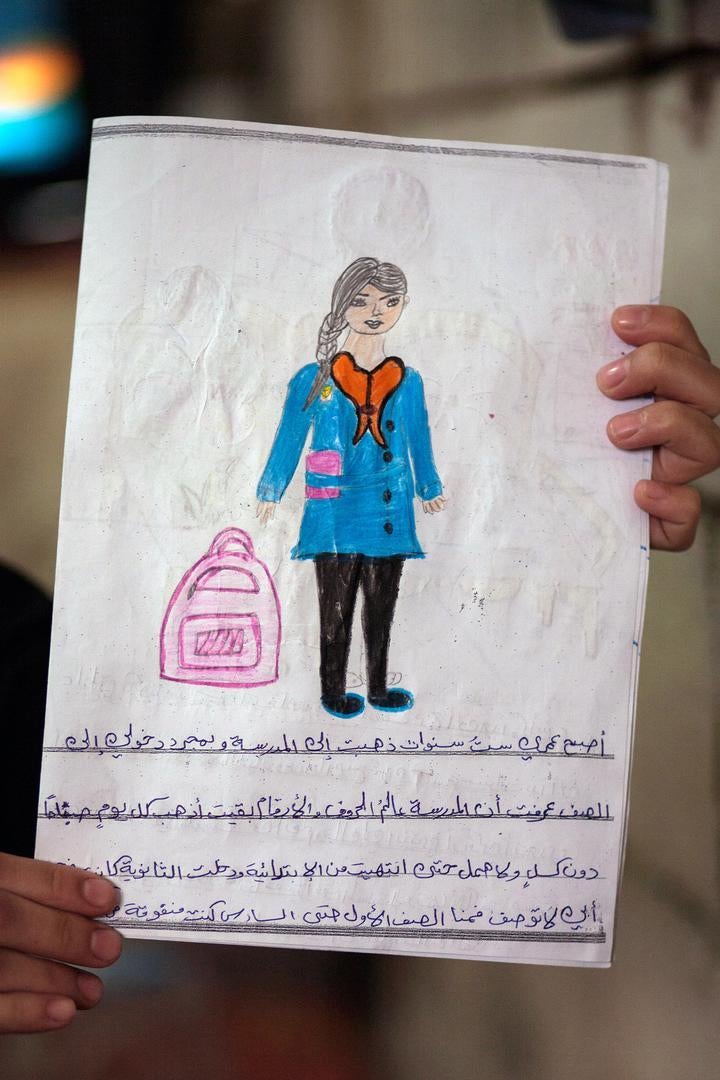

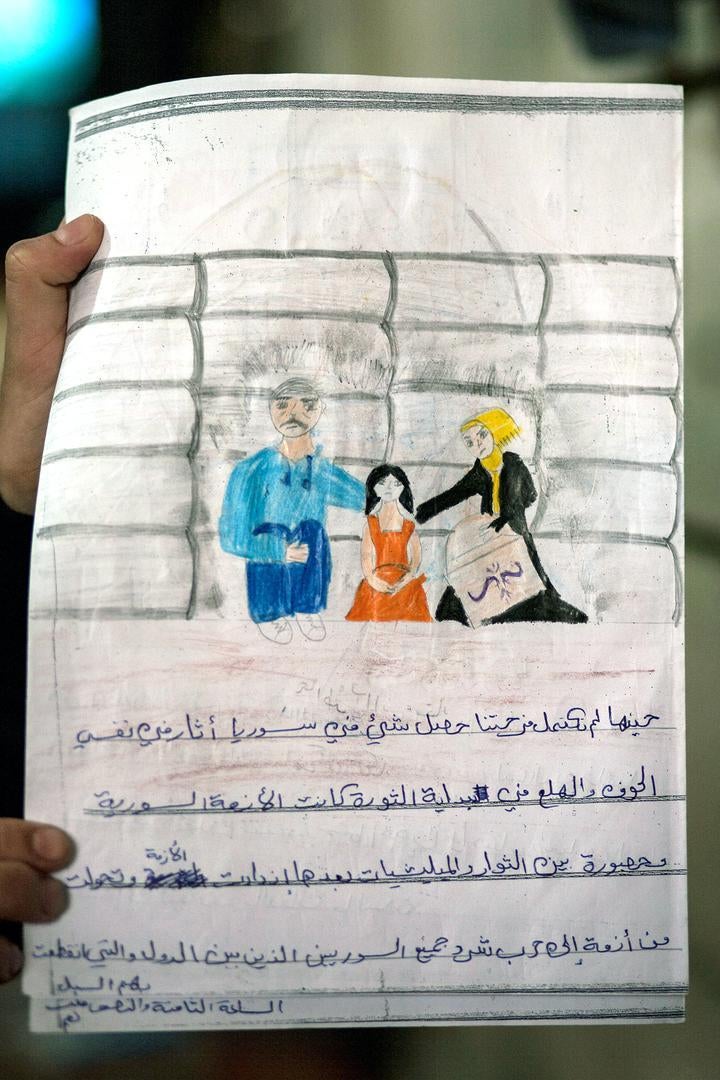

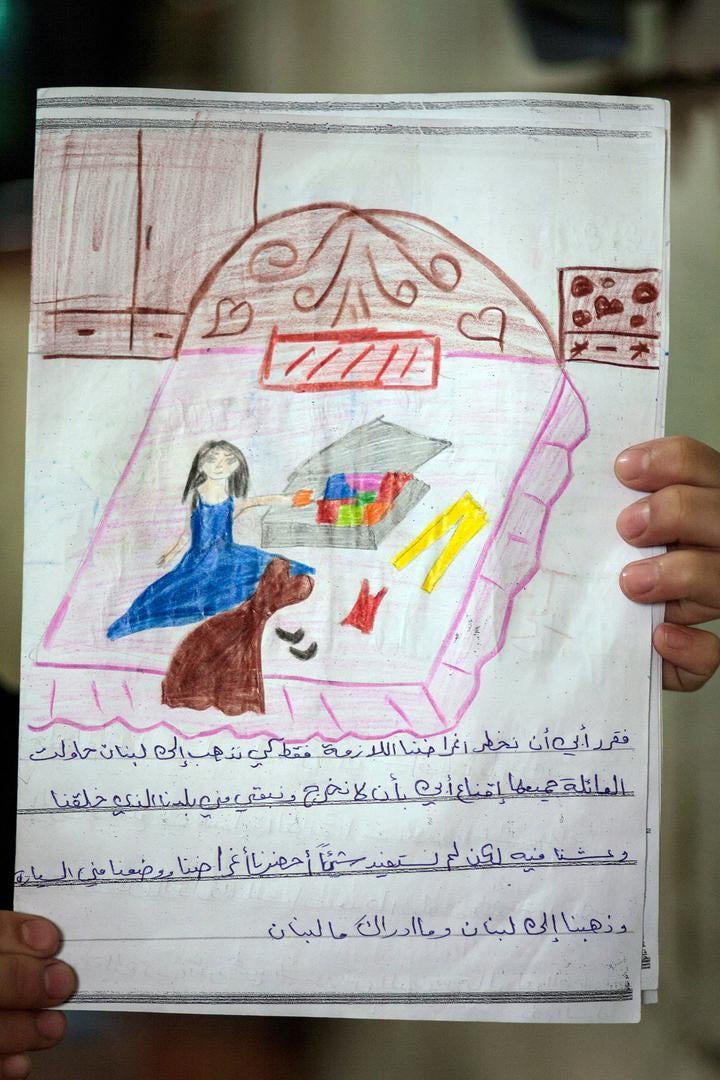

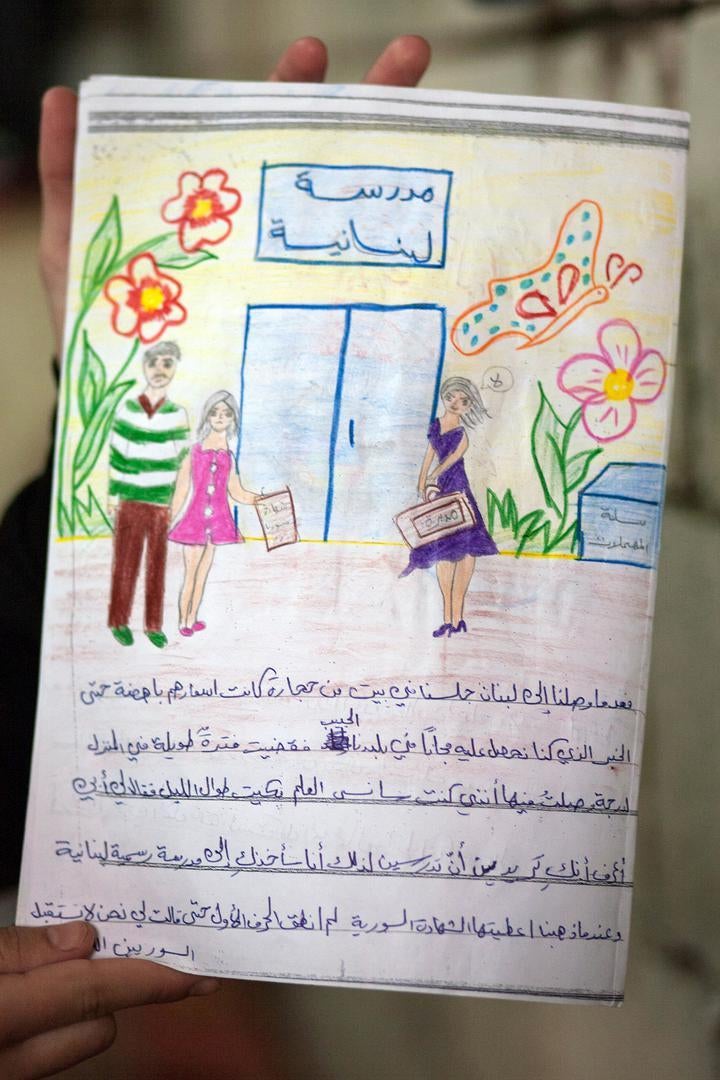

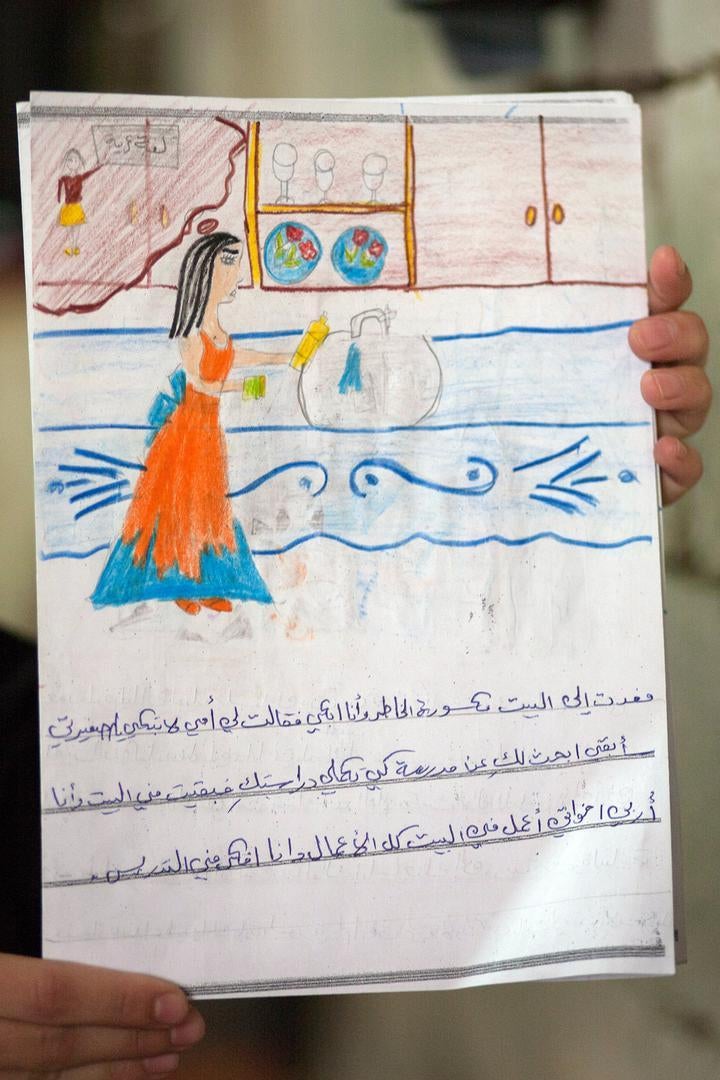

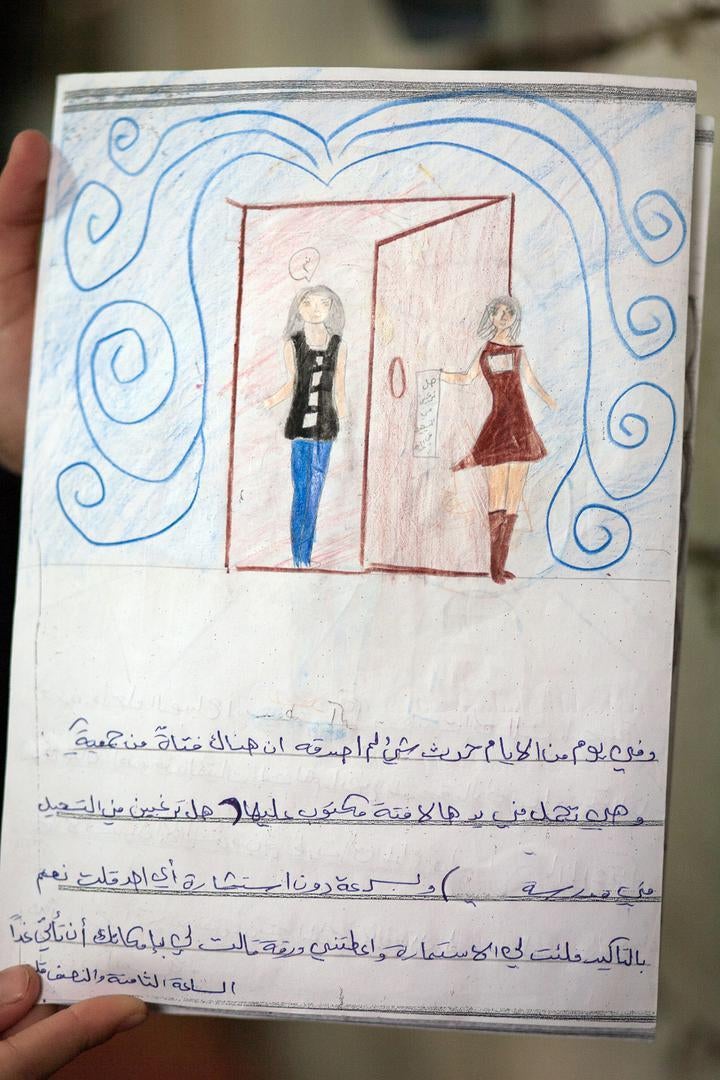

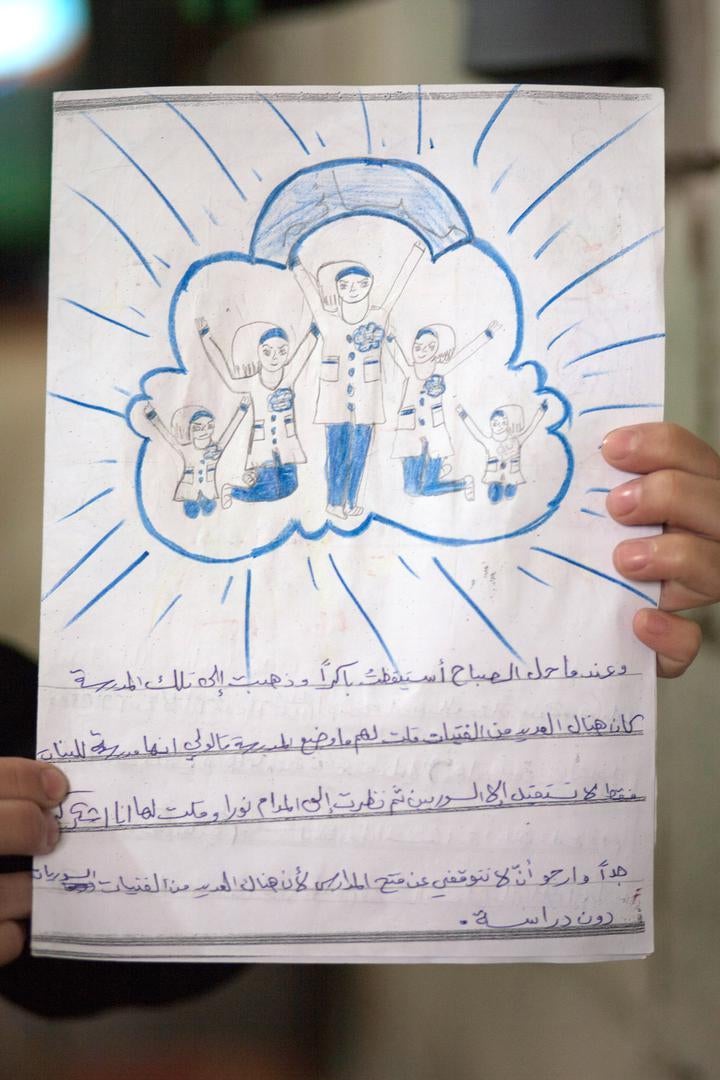

In November and December 2015, and February 2016, Human Rights Watch conducted 156 interviews with Syrian refugees, gathering information about the situation of more than 500 school-aged children. Some had been out of school since arriving in Lebanon five years ago. Others had never stepped inside a classroom.

Of the Syrian refugees registered with the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) in Lebanon, nearly 500,000 are between the ages of 3 and 18, considered school-aged by Lebanon’s Education Ministry. But only 158,000 “non-Lebanese” children, the vast majority Syrian, enrolled in public schools for the 2015-16 school year, and an additional 87,000 non-Lebanese children enrolled in private and “semi-private” schools, according to the ministry. An unknown number of out-of-school children are among the estimated 400,000 Syrians in Lebanon not registered with UNHCR, which ceased registration of Syrian refugees in May 2015 at the instruction of the Lebanese government.

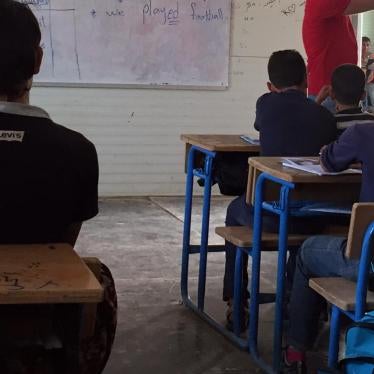

Lebanon has allowed Syrian refugees to enroll in public schools for free and without residency, and increased school capacity by opening a second “afternoon” shift for Syrian children in 238 schools in 2015-16. In September, the Education Ministry announced plans to enroll 200,000 Syrian refugees in formal public education, with international support, as part of the Reaching All Children with Education policy adopted in June 2014.

The number of classroom spaces for Syrian children in Lebanese public schools has increased every year since the Syria conflict began in 2011. In 2015-16, however, schools still turned away Syrian children because available spaces were not necessarily located in areas of need, or children faced other barriers. Of the 200,000 school spaces that donors committed to funding for Syrian children, almost 50,000 ultimately went unused.

Harsh regulations that prevent most refugees from maintaining legal residency or working are undermining Lebanon’s generous school enrollment policies. Many families fear arrest if caught working or trying to find work. With 70 percent of Syrian families living below the poverty line in 2015, many cannot afford school-related costs like transportation and school supplies, or rely on their children to work instead of attending school.

Rana, 31, who fled from the outskirts of Damascus to Lebanon in 2012, said she had to quit her job in a pastry shop because she feared arrest after her residency expired. As a result, she could not afford to send her children to school. Now, her 10-year-old son Hamza is selling chewing gum on the street. “If there were no fees then we would of course enroll our children in school, but we can’t cover the cost of transportation,” she said. “My children should learn to write their names. It’s over for us, should it be over for our children as well?”

“Lebanon should urgently reform a counterproductive residency policy that is forcing Syrians underground and affecting parents’ ability to send their children to school,” Khawaja said.

Other factors that deter Syrians from enrolling and lead to dropouts include arbitrary enrollment requirements imposed by some school directors; violence in schools, including corporal punishment by staff and bullying and harassment by other students; safety concerns, with many children walking home from evening classes that end after dark; and classes taught in unfamiliar languages, such as English and French, with insufficient language support.

Kawthar, 33, said that when she tried to enroll her children in fall 2015, one school demanded several documents that the Education Ministry does not officially require, including vaccination records she left behind when fleeing Syria. She was eventually able to enroll her children, but pulled them out after three months because they never received textbooks and she could not afford to keep paying for their transportation.

Secondary-school age children face particular barriers, including greater distances to schools, the near impossibility of maintaining legal residency after turning 15, and increased pressure to work. Only 2,280 “non-Lebanese” students enrolled in public secondary schools in 2015-16, just 3 percent of registered secondary school-age Syrian children.

Syrian children with disabilities face particularly daunting challenges. Public schools, which have a poor record including Lebanese children with disabilities, often reject them, saying they lack the resources or skills to educate them. When Syrian children with disabilities are able to enroll, public schools do not ensure they receive a quality education on an equal basis with others.

Some Syrian children have benefited from non-formal education programs run by non-governmental organizations (NGOs), often in informal refugee camps. But some groups told Human Rights Watch that the Education Ministry withdrew support for their programs last year, or that they discontinued programs because it was unclear what they were allowed to provide. The Education Ministry has since adopted a policy framework for non-formal education, and in January launched an accelerated learning program for children who have missed two or more years of school. However, officially approved programs to reach children who cannot attend formal schools remain limited.

Lebanon says that lost revenue due to the war in Syria and the burden of hosting refugees have cost the country an estimated US$13.1 billion. Meanwhile, the Lebanon Crisis Response Plan was only 62.8 percent funded in 2015. Lebanon needs much more international financial support to respond to the educational needs of Syrian refugees. But funding additional classroom spaces alone will not necessarily mitigate the obstacles preventing Syrian children from going to school unless Lebanon changes policies that have limited children’s access.

International support for the country’s public school system will also benefit Lebanese children, many of whom have experienced similar barriers. In 2015-16, international donors covered the school fees for all 197,010 Lebanese students enrolled in basic education.

Lebanon should ensure that its generous enrollment policy is properly implemented and that there is accountability for violence in schools, including corporal punishment, Human Rights Watch said. The Education Ministry should allow NGOs to provide regulated, quality non-formal education, at least until formal education is accessible to all children in the country.

The government should revise its residency requirements and allow those whose status has expired to regularize. It should also operationalize its Statement of Intent presented at a London donor conference in February and review the regulatory frameworks related to work authorization for Syrians.

“Opening places in schools will not resolve the challenges of educating so many Syrian children, unless Lebanon and the international community tackle the underlying barriers keeping children out of the classroom,” Khawaja said. “It’s in everyone’s interest to ensure that all children in Lebanon can get an education, but the longer children are out of school, the less likely they are to return.”

“Growing Up Without an Education” is the second of a three-part series addressing the urgent issue of access to education for Syrian refugee children in Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan.

Quotes from the report

“We can’t afford to put them in school here. All my children were studying in Syria, but if I would put them in school here, how would I live? We would have to buy them clothes and pay for transportation. Even if everything was free, the children couldn’t go to school. They are the only ones that can work.” – “Muna,” 45, Mount Lebanon

“The kids’ education has gone backward. They don’t have a future. We left our country and our homes and now they don’t even have an education or a future.”– Jawaher, 24, North Lebanon

“I tried to register at three schools. The first told me they were only registering third grade and higher. The second school wouldn’t accept him, the director told me ‘No Syrians.’ I tried to tell him about the new rules, and he said: ‘The UN has nothing to do with us, we know what we’re doing. There’s no more space.’” – Afaf, 45, Beirut

“He’s smart but it was too hard. He was a very good student. It was the foreign languages that were too hard for him…. There was no special help for languages, and no special teachers were affordable for us. Now he’s sitting at home.” – Ramad, 35, Bekaa Valley

“I went to a public school for one month, they hit us…. They put a piece of wood on my head and hit it. They hit me 10 times while I was at school. They hit the girls as well.... After one month I told my mother I didn’t want to go to school.” – Khalifeh, 8, Bekaa Valley

“I started working when I arrived, in cement and construction. The work here is really hard. I started when I was 13…. I’ve been here five years and have lost five years of my life.” – Amin, 18, North Lebanon

“I wish he was learning. I don’t want him working. If you don’t know how to read, you’re lost. It’s like me, I don’t know how to read and I’m lost. No mother would ever accept that her son stay in the dark.” – Ilham, 30, North Lebanon .