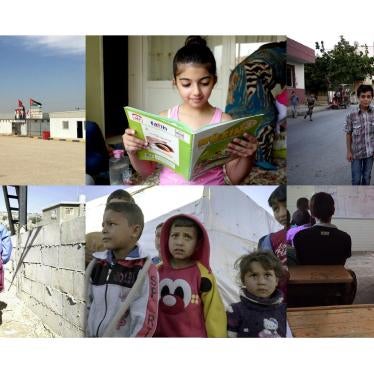

For Racha, a 30-year-old Syrian refugee in Lebanon, €30 per month is the difference between putting her three children in school and watching them grow up without an education. “This year, I was able to register them but couldn’t afford the transportation fee,” she told me. Her 6-year-old daughter, Dana, cries because she’s not going to school, Racha said. “I’m alive, their dad is gone. I don’t want them to lose out.”

Lebanon, a small country of about 4.5 million citizens, has taken on an enormous burden, hosting 1.1 million registered Syrian refugees. The government estimates the total, including unregistered Syrians, is 1.5 million. Racha’s children are among the more than 250,000 school-age Syrians there who are out of school. With international assistance, the Education Ministry has opened public schools to Syrian refugees, and 158,000 enrolled last year. The Education Ministry estimates another 87,000 are in private schools. But five years into the war in Syria, the number of refugee children still out of school is an immediate crisis.

My research for Human Rights Watch found that donor support, and pressure, are needed to eliminate barriers that are still keeping children out of school. As leading donors, the European Commission and European Union member states have a critical role to play for children’s fundamental right to an education, Lebanon’s stability, and Syria’s future.

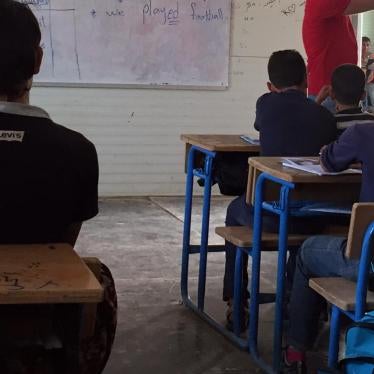

Lebanon needs sustained and targeted support to prevent a generation of Syrian children from growing up without an education. International donors paid €240.9 million for education in 2015 as part of the Lebanon Crisis Response Plan, including €327 for every Syrian student in regular, “morning shift” classes and €541 per child in the “afternoon shift” added to accommodate Syrian students. But even before the refugee crisis, the public school system in Lebanon struggled; the parents of only 30 percent of children chose to send them to public schools. Now, the nearly 500,000 school-age Syrian children in Lebanon are almost double the number of Lebanese children in public schools.

With more than 70 percent of Syrian families in Lebanon living below the poverty line, subsidized transportation is needed to get more children into school. But enrolling children is only the first step—providing a quality education is key to preventing dropouts. Syrian children need trained teachers, mental health support, and accelerated programs to teach English and French, the unfamiliar languages of instruction in Lebanon.

With humanitarian assistance focused on basic education, some children have been left behind. Parents of children with disabilities told me they were turned away from public schools—or marginalized in the classroom. Secondary-school age children face increased pressure to work and support their families, coupled with tightened restrictions on freedom of movement, and greater distances to schools. Just 3 percent of Syrian children ages 15 to 18 are enrolled in Lebanon’s public secondary schools.

But international assistance for education will only go so far. Lebanon also needs to make common-sense policy changes to ensure that refugees’ living conditions allow them to keep their children in school.

European donors should encourage Lebanon to reform a flawed residency policy that sets high and expensive barriers for Syrians to maintain legal status, with serious consequences for children’s education. An estimated two-thirds of Syrians have lost their legal status since the introduction of the new regulations in January 2015.

Without legal residency, refugees are unable to move within the country or find work without fear of arrest. Most families have used up their savings, and few can afford transportation and school supplies. Others rely on their children, who are less likely to get stopped at checkpoints, to work instead of attending school. Unless Lebanon changes this counterproductive policy, increased funding for education will not be enough to get all children into school.

But families and their children are still eager for an education. Some have gone into debt to enroll their children or moved closer to schools that might accept them. One woman I interviewed temporarily moved back to Syria after failing to get her children in school in Lebanon. But no parent should be forced to choose between an education for their children and returning to a war zone.

European donors should encourage Lebanon to revise policies keeping children out of school, increase resettlement of refugees from Lebanon, and step up targeted financial support. Lebanon needs help, and the children who fled the horrors of war in Syria need the tools to build a better future for themselves and their country.