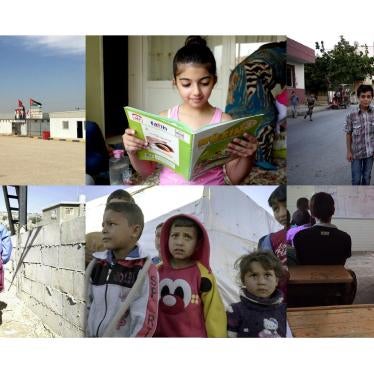

When students sit this week for the baccalaureate exams that mark the end of high school in Lebanon, Amin, 18, won’t be among them. He has been out of school since fleeing to Lebanon as a refugee from Syria. “I’ve been here five years and lost five years of my life,” he said.

Amin’s brother Anas, 16, dropped out after he wasn’t able to enroll in grade nine. School officials told him that he would have to pay for transportation to a school more than an hour away. But there was an even bigger obstacle: “We couldn’t go because there are checkpoints and they might arrest us,” said Anas, who hasn’t been able to maintain legal residency in Lebanon. Now, both brothers work in construction.

Despite the Education Ministry’s efforts to improve enrollment, Syrian families told me that secondary-aged children face particular barriers – documentation requirements, classes taught entirely in unfamiliar English or French, greater distances to schools, and pressure to work to support their families.

One major barrier that Lebanon could easily change is its residency policy, which requires Syrians, the vast majority of whom are impoverished or indebted, to pay $200 per year for every person aged 15 or older. Children turning 15 face particular challenges to renewal, because many do not possess the required passport or individual identification card. Humanitarian organizations estimate that two-thirds of refugees have lost their legal status as a result and are vulnerable to arrest at checkpoints on the way to school.

Lebanese authorities caught both Anas and Amin without residency documents, and their expired papers now bear removal orders stating, “Last chance to get ID or passport or to leave.” Although Lebanon isn’t currently carrying out such orders, both brothers fear deportation to Syria if caught again.

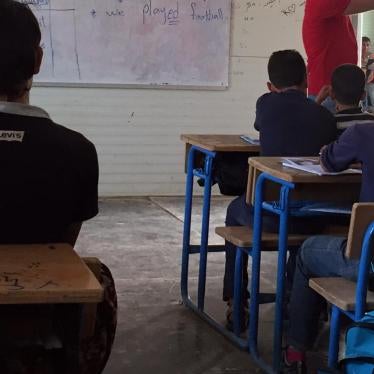

At the beginning of the school year, 82,744 Syrians of secondary school age were registered with the United Nations refugee agency in Lebanon, but only 2,280 non-Lebanese students were enrolled in public secondary schools as of March – less than 3 percent of the total. By comparison, 150,000 non-Lebanese children enrolled in public basic education this year.

Lebanon has taken some steps to ease restrictions on secondary school enrollment for Syrian children. In March, the Education Ministry stopped requiring Syrians to present transcripts to take the Brevet exam, which is required for admission to secondary schools. And a UNESCO program now covers secondary school enrollment fees for non-Lebanese students.

But unless the Lebanese government, international donors, and humanitarian agencies address the broader obstacles preventing children from continuing their education, most Syrian children will never reach secondary school.