Nearly 20 per cent of the world’s fresh water is in Canada. Most Canadians have nearly unlimited access to pristine drinking water – most, that is, except the country’s indigenous First Nation communities. Nearly one-third of First Nation communities in Ontario, Canada’s most populous province, are subject to so-called water advisories – government notices telling people to boil or avoid drinking the water, which could contain harmful bacteria or even uranium. Human Rights Watch senior researcher Amanda Klasing talks to Amy Braunschweiger about how it’s possible that, with water everywhere, there’s somehow none for so many to drink.

What’s happening in these First Nation communities?

These communities have contaminants such as E. coli, Cryptosporidian, giardia, or uranium in their water. Many people we spoke with reported skin conditions like itchiness, eczema, sores, and even antibiotic-resistant strains of staph infections that they believe were either caused by the water in their community or exacerbated by bathing in the water.

Across 40 of Ontario’s First Nation communities there are 90-something drinking water advisories, as some communities have more than one. As there are 133 First Nation Communities in the province, this a significant number. Water advisories occur much more frequently there than in the rest of Ontario, and they last longer. Some communities like Neskantaga First Nation and Shoal Lake 40 First Nation have been on boil-water advisories for two decades.

Many of these water systems have problems with what’s called “disinfectant byproduct,” which can occur when you have a lot of organic material – dirt, sewage, dead trees –in your water. When these aren’t filtered out, and you add chlorine to kill the bacteria that make you sick, the chlorine interacts with these organic materials to create disinfectant byproducts, which can cause cancer over long periods of exposure.

Twenty percent of First Nation households in Ontario mostly rely on well water, which isn’t covered by these advisories but may also be contaminated. For example, uranium shows up in wells. It occurs naturally in the ground in some of the communities we visited—Batchewana First Nation and Grassy Narrows First Nation. Exposure to Uranium over decades may cause cancer and harm kidneys.

How are people reacting to this?

Whether or not there are immediate health effects, people are anxious, thinking the water is poisoning them. They don’t have enough information about what’s going on, and they don’t know how to fix it. And I get it. People shouldn’t have to drink water with the risk that there may be cancer causing agents in it – that’s a fair thing for them to ask.

Also, they can’t just move away to an area with safe drinking water. Canada’s First Nation communities live on reserves, plots of land designated for them them by the government. There’s nowhere to move to.

How is this possible in Canada?

Providing clean drinking water seems like it should be easy, but it hasn’t been. Canada’s lakes and rivers aren’t pristine anymore. Water needs more processing, either because of industry waste or sewage or other polluting activities.

In Canada, water is under provincial authority, but that ends at reserve borders because the federal government has responsibility for everything on reserves, including the water.

Many reserves had water treatment systems built in the 1990s. For some communities, it was the first time they had running water in their homes. But many of the plants the government built haven’t lasted in some communities. And they wouldn’t have been up to code if they’d been built elsewhere in Ontario.

For example, the plant in the Shoal Lake 40 pumps water from a nearby lake, adds chlorine, and then pumps it into people’s homes. But there’re potential contaminants in this water – amoebas, giardia – that chorine doesn’t kill. You need filtration.

Shouldn’t these plants have been updated by now?

The federal government has pledged to end the long-term boil-water advisory in five years, and it does provide bottled water or a filtration station where people can fill up bottles in communities with ”do not consume” advisories. But it’s not enough to fix the problem.

The government passed a Safe Drinking Water Act for First Nations in 2013. Problematically, it was passed over the objection of many First Nation leaders, who didn’t feel properly consulted. Under the act, if something goes wrong with the water supply, there could be financial or criminal implications for First Nation leaders. The First Nations wouldn’t necessarily object to this – if the water plants and systems were good quality. But they aren’t.

For the First Nations, it looks like the federal government is trying to unload a problem onto them without giving them proper support.

The idea behind this act was that the communities would receive financial support and the water systems would be brought up to code before the transfer. But this hasn’t happened, in part because the money the government spent wasn’t attached to specific outcomes for water quality.

Also, many of these communities are below poverty level. The government does pay 80 percent of the costs associated with running a water or wastewater system, but it’s insurmountable for most communities to come up with the remaining 20 percent.

I also think the government believed they’d be able to engage with the First Nations, but that hasn’t gone well.

Why not?

A history of racism, abuse, and mistrust underlies everything. First Nation reserves are governed by the Indian Act, which is more than 100 years old. It was a pretty nasty piece of legislation when it was written, although it’s been reformed some over time. When the law was first put in place, First Nation people couldn’t leave their reserve without permission. Until 1950s, First Nations couldn’t employ a lawyer.

Aspects of this act enabled the rise of the “residential school system,” where native children were forced into schools away from their families and often subject to terrible physical and sexual abuse. They weren’t allowed to speak their own language. Thousands of children died in these schools. Last year, Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission finished a damning report on the schools.

I was surprised how often residential schools came up in my interviews. Many community leaders and elders had been forced into residential schools. The trauma of this impacts the way they interact with the government.

I hoped to speak with one community leader about water quality, but within five minutes he was detailing the impact of the sexual abuse he experienced at the school. He sees this trauma replicated in how difficult it is for his family to drink clean water. He sees a parallel between his situation and that of his children and grandchildren.

How have the problems with unsafe water affected people?

People are changing their personal hygiene. Mothers of small children don’t want to wash their children in unsafe water. So either they boil enough water for a bath, letting it cool down – which can take an extra hour or two – or they try to bathe their kids in bottled water. Kids are getting bathed less frequently.

One mom I spoke with in Neskantaga First Nation had a 4 month-old son with a heart condition. Washing his bottles was an hour-long affair because she had to make sure the water was safe.

Did you speak to anyone who stood out to you?

I spoke with one mother of a 2-year-old daughter in Grassy Narrows First Nation whose well water was contaminated with uranium. So she began getting water trucked in from the community’s water system, but it was under a “do not consume” advisory. Then her daughter broke out in sores that wouldn’t clear up. Her doctor blamed the water. So now this mother takes her daughter to a relative’s home every day to give her a bath.

This was a working mom, and she looked so tired, just exhausted. As a mom of a young kid, I can’t imagine, at the end of a long work day, having to have remove my child from the house in – in the dead of winter when it’s negative 27 degrees outside – and go to a neighbor or family member’s house just to bathe them.

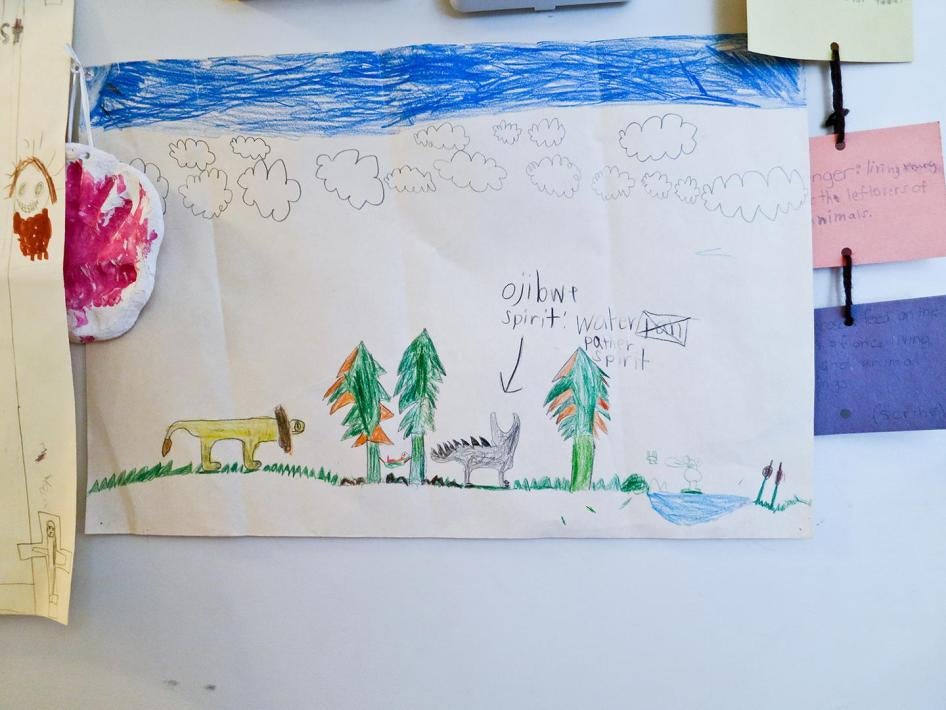

Does water have a traditional significance for First Nations?

Within first nation communities and cultures, women have the role of keeping and protecting water. They believe that there’s a mutual responsibility between people and water, that water keeps us alive, and that we’re responsible for keeping water safe.

Female elders, some known as Water Walkers or Water Grandmothers, conduct water ceremonies. Particularly for the water keepers, there’s this real sense of urgency and loss related to the destruction of water sources. And it’s not just because it’s impacting their health. They really feel that something alive is being harmed and they’re powerless to stop it.

I’ve been to maybe six ceremonies. They’re really moving. It’s a moment of solemnity. Within the process, the water becomes an entity. Water is something you have a relationship with. I feel so honored that I’ve been allowed to participate.

In one ceremony we actually stood in the water. It was freezing but moving to the point that I was teary eyed. Was it because the ceremony was so beautiful? There’s a sadness about this water crisis that goes beyond the fact that this water might make them sick. In the space of these ceremonies, you could just feel the emotional impact of this loss.

What do you want to see happen?

The government has pledged to end the long-term boil water advisory in five years, and now’s the time for it to act. Over the past 20 years the government has invested billions in water for these communities, but it needs to set clear goals and indicators for how the money is to be used, and there needs to be accountability for positive outcomes in this spending. Also, having a First Nation-led water commission that works with the government to monitor implementation is important. These communities need to fully participate on both the local and national level.

This interview has been edited and condensed.