Param-Preet Singh of Human Rights Watch considers that too little has been done to deliver justice for the human rights violations committed during the electoral crisis of 2010-2011.

Five years ago, Côte d'Ivoire’s was embroiled in a five month civil war, where both sides committed crimes that left at least 3,000 civilians dead and more than 150 women raped in a conflict waged along political, and, at times, ethnic and religious lines.

But five years later, no one has been held to account in the country’s civilian courts for the horrific abuses committed during that period.

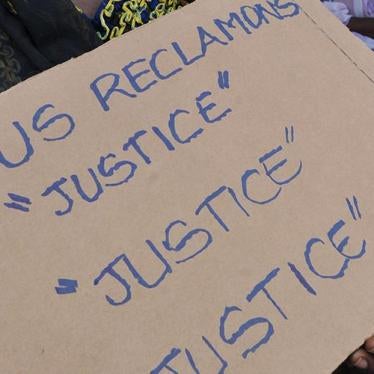

“We have suffered too much”

The demand for justice has not diminished with time. As one victim of sexual violence told Human Rights Watch last year, “The people responsible for abuses must be punished. We have suffered too much.” Another victim told us, “If justice does its job, we can forgive.”

Justice for these crimes has long been a staple of President Alassane Ouattara’s rhetoric. When he took office in mid-2011, he promised to hold to account those responsible for the abuses during the period after the former president, Laurent Gbagbo, refused to cede power to Ouattara, the internationally recognized winner of the November 2010 presidential election. In June, 2011, Ouattara established a task force of judges and prosecutors, the Special Investigative and Examination Cell, to handle prosecutions of crimes during that period.

In late 2011, President Ouattara surrendered Gbagbo to the International Criminal Court and in early 2014 surrendered his close ally, Charles Blé Goudé. Their joint trial on four counts of crimes against humanity allegedly committed during the 2010-2011 crisis began in The Hague earlier this year.

President Ouattara said after his October 2015 reelection that he remains committed to prosecuting those who committed abuses during the 2010-2011 post-election crisis, and that, “justice must be equal for all; we need to avoid impunity.” Ouattara also said that Côte d’Ivoire’s justice system is now operational, and there is no need to surrender any more suspects to the ICC, a sentiment repeated to me last week in Abidjan by a ministry of justice official.

A second trial for Simone Gbagbo?

Yet justice remains elusive for most victims. “We speak about justice, but where is this justice?” a Yopougon resident who voted for Gbagbo in 2010 told Human Rights Watch.

In late 2014, after more than three years of operating in the shadows, the special cell received increased resources from the government, and in 2015 brought charges against more than 20 people—including high-level commanders from both sides. And last week, it was revealed that former First Lady Simone Gbagbo, who is also wanted by the ICC, may soon be tried in an Ivorian court for human rights crimes.

Victims will only get the justice they deserve if the process is independent, impartial and fair. Establishing the truth about criminal responsibility in a credible process is especially important in a polarized landscape like Côte d’Ivoire, where both sides cling to their own version of the 2010-2011 events.

Indeed, the risks associated with delivering flawed justice are very real. The trial and conviction of Simone Gbagbo in March 2015 for crimes against the state—not human rights abuses—was riddled with fair trial concerns. The flaws in the process lent weight to efforts by Simone Gbagbo and her supporters to question the legitimacy of the proceedings and denounce the verdict.

Maintaining support for investigations is critical. Cases must be built on solid evidence to withstand rigorous scrutiny in court. But a number of key areas need more support from the government—and its new justice minister, Sansan Kambile—if Ivorian courts are to deliver fair and credible justice.

Strengthening the independence of judges to decide cases without political interference or fear of retaliation remains a linchpin of a credible process, along with protecting witnesses, judges and lawyers from threats.

The government should also make it a priority to carry out legal reforms to protect fair trial rights. Since many defendants have been sitting in pretrial detention for years awaiting trial, judges should release any defendants who don’t pose a threat to witnesses and aren’t a flight risk.

Finally, in light of his the concerns raised by the president’s remarks about presidential pardons, he should make clear that pardons are not available for those convicted of serious abuses.

Côte d’Ivoire’s international partners, including France, the European Union and the United States should lend political, technical and financial support where needed by the country’s justice system.

And the ICC, whose prosecutor says that investigations on the Ouattara side have “intensified,” though they have not yet yielded arrest warrants, should continue those efforts. The ICC’s investigations remain a vital path to justice for victims of crimes by Ouattara loyalists, and can help the court regain some of its credibility because of its one-sided approach to date.

Justice should remain a core feature of President Ouattara’s second term. As one activist told Human Rights Watch, “fighting against impunity is to guarantee a society more justice, more peace and more serenity.”

-------------

Param-Preet Singh is senior international justice counsel at Human Rights Watch, and main author of the new Human Rights Watch report “Justice Reestablishes Balance: Delivering Credible Accountability for Serious Abuses in Côte d’Ivoire.”.