Summary

“We want to end impunity in Ivory Coast. No one is above the law. All those that committed blood crimes will be punished ... There will be no exceptions.”

—Ivorian President Alassane Ouattara, Dakar, May 2011

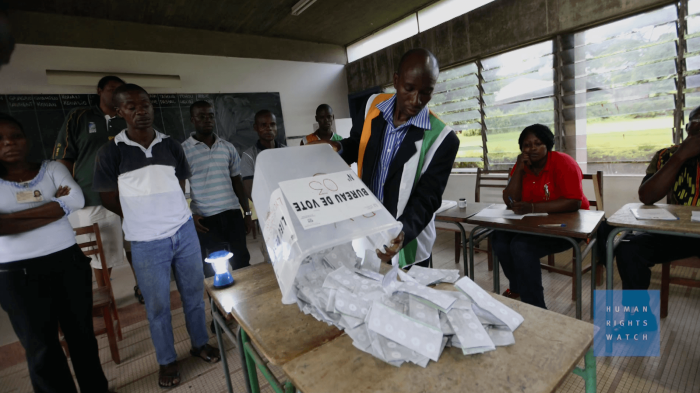

In October 2015, Ivorians gave President Alassane Ouattara another five-year mandate in an electoral process that the African Union and the Economic Community of West African States considered largely free and fair.

The October presidential election was the first since the country’s 2010 polls, when the failure of incumbent President Laurent Gbagbo to cede power to Ouattara triggered a five-month conflict during which forces loyal to both sides committed serious human rights violations. Civilians were summarily executed. Women were brutally gang-raped. Villages were burned to the ground. By the end of the conflict, at least 3,000 civilians were killed and more than 150 women raped during violence that was waged along political, and, at times, ethnic, and religious lines.

The 2010-2011 crisis was the culmination of a decade-long cycle of political violence and impunity, which included election-related abuses in 2000 and a 2002-2003 armed conflict, during which perpetrators of human rights violations escaped prosecution for their crimes. Many of those who were implicated in past abuses went on to commit crimes during the 2010-2011 crisis, a stark reminder of the high cost of impunity.

When President Ouattara finally took office in May 2011, he promised to bring the perpetrators of post-election abuses to justice. To an extent, there has been progress at the international level: Gbagbo and Charles Blé Goudé, a former youth minister and leader of a pro-Gbagbo militia group, are currently on trial before the International Criminal Court (ICC) on charges of crimes against humanity.

The ICC has also charged Gbagbo’s wife, Simone, with crimes against humanity committed during the post-election crisis, but Côte d’Ivoire has still not transferred her to The Hague, despite its obligation to do so as a member of the court. The ICC has yet to take concrete action against any member of the pro-Ouattara forces, although ICC Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda has repeatedly stressed that her office’s investigations, which are ongoing, are impartial.

At the national level, Ouattara established several mechanisms aimed at promoting truth seeking and accountability, including a national commission of inquiry to investigate and document abuses committed during the crisis and, in June 2011, a taskforce of judges and prosecutors, known as the Special Investigative and Examination Cell, to handle prosecutions of crimes related to the post-election violence. The commission of inquiry published a summary of its findings in August 2012, concluding that crimes had been committed during the 2010-2011 crisis by forces loyal to both Gbagbo and Ouattara and stressing the importance of trying all perpetrators, regardless of their affiliation.

President Ouattara’s creation of the special cell to spearhead efforts to pursue perpetrators in national courts offered hope that, finally, the government was taking concrete steps to address Côte d’Ivoire’s deeply entrenched culture of impunity. Investigations of serious international crimes are complex and require specialized expertise; some investigations can take years. Consolidating resources, expertise and support into one unit was a promising step.

Yet it was not until late 2014–more than three years after its creation–that the government started providing consistent support to the special cell to fulfill its mandate. More recently, the cell has been able to make progress, which is encouraging, but victims will only receive justice if perpetrators receive trials that are independent, impartial and fair.

Based on interviews conducted by Human Rights Watch with more than 70 people, including Ivorian government officials, members of the judiciary, representatives of civil society groups, international criminal justice experts, UN officials, diplomats, and donor officials, this report outlines critical areas requiring additional government support so that Côte d’Ivoire can deliver credible justice. Notably, in addition to maintaining support for investigations, the government should take steps to strengthen the independence of the judiciary; protect judges, lawyers, and witnesses involved in sensitive cases; and support legal reforms that would respect the fair trial rights of defendants. President Ouattara should also make clear that presidential pardons are not available for those convicted of serious abuses.

A History of Uneven Support

National accountability efforts inevitably depend heavily on the government’s financial and political support, which initially the Ivorian government was very slow to provide to the special cell.

From its inception until late 2014, the work of the special cell was marred by staffing shortages and budgetary constraints. In late 2013, a government spokesperson said the cell would imminently close, and, while it continued to operate, its existence seemed precarious. In the face of these obstacles, the cell made very limited progress in its investigations into either side’s role in human rights violations.

Beginning in late 2014, the government finally started providing the cell with the backing it needs to effectively investigate post-election abuses. The staffing in the cell has remained stable, and it has an adequate budget to conduct investigations.

The special cell in 2015 made significant progress in cases involving human rights abuses committed during the post-election crisis. Investigations are targeting high-level members of pro-Gbagbo and, importantly, pro-Ouattara forces, including those currently occupying key positions in the Ivorian army.

But the government’s shift in favor of supporting justice, while welcome, seems fragile. Several international diplomats and other observers interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that this shift could be explained by two factors: the recent presidential election and the need to deliver on past and more recent promises, and the ICC’s work in Côte d’Ivoire, including its heightened focus on abuses committed by pro-Ouattara forces.

That the government’s support for accountability may be linked to these factors raises concerns about its durability over the long term. In mid-2015, amid progress in investigations in human rights abuses committed during the 2010-2011 crisis, Human Rights Watch learned that the executive was pressuring the cell to finish its work prematurely, which threatened to undermine the quality of the special cell’s investigations. While the investigations ultimately moved forward, the process remains susceptible to executive interference.

The risks associated with delivering flawed justice are very real, as illustrated by last year’s trial and conviction of former First Lady Simone Gbagbo for crimes against the state. Gbagbo’s trial and 20-year sentence, which was twice the sentence requested by the prosecution, was marred by a number of fair trial concerns. These concerns have lent weight to efforts by Simone Gbagbo and her supporters to publicly denounce the guilty verdict and question the legitimacy of the proceedings.

Since perpetrators of the 2010-2011 post-election abuses often acted against rival political factions, and, at times, against members of rival ethnic and religious groups, the stakes are especially high for fairly adjudicating the crimes. A justice process that is independent, impartial, based on solid evidence, and respectful of a defendant’s fair trial rights is essential to give victims the redress they deserve. Credible justice is also better equipped to withstand efforts to politicize the outcome and help cement the rule of law in Côte d’Ivoire.

Concrete Steps to Support Credible Justice

President Ouattara said after his reelection that he remains committed to prosecuting those who committed abuses during the 2010-2011 post-election crisis, and that, “justice must be equal for all; we need to avoid impunity.” Ouattara has also stated that Côte d’Ivoire’s justice system is now operational, and there is no need to surrender any more suspects to the ICC.

The conduct of cases related to the crisis, which will be closely scrutinized by the ICC and the international community more broadly, will be a test of how much Côte d’Ivoire’s justice system has improved since President Ouattara came to power. Moving forward, there are a number of steps Côte d’Ivoire’s government—and its new justice minister, Sansan Kambile—can take to more effectively prioritize justice.

First, it remains critical that the government maintains its support for the special cell’s investigations. The government should make clear its intention to support the cell’s work and its operational independence. The government should also maintain the current staffing in the cell and continue to provide the resources needed to do its work. Further, given the complexity of addressing allegations of serious human rights violations, the government should invite or support efforts by the cell’s investigating judges—and by the trial judges who will ultimately hear cases—to seek assistance and training from outside experts as needed.

The judiciary must also be able to act with independence and impartiality to build the rule of law. In Côte d’Ivoire, as in many other countries recovering from conflict, sensitive cases involving grave abuses are highly politicized. Côte d’Ivoire has a long history of executive interference in judicial decision-making, a concern that has persisted during President Ouattara’s time in office. The government should strengthen the legal architecture—which includes revising the constitution and passing a law on the profession of magistrates—to help close the loopholes that would otherwise facilitate political interference.

Judges, prosecutors, and witnesses must also be able to participate without fear. There is still no framework to provide protection to judges, prosecutors, lawyers and witnesses. The lack of any system of formal or informal protection risks exposing these actors to threats or reprisals, compromising their ability to effectively participate in proceedings. The government is currently reviewing legislation to protect witnesses, and should take steps to make passage of the law a priority. The government should also take to steps to more effectively protect judicial officers engaged in sensitive cases.

Due process is a critical component of credible justice. There has been some momentum in bringing Côte d’Ivoire’s criminal law in line with its obligations under the Rome Statute. However, many defendants who were arrested during or shortly after the 2010-2011 crisis remain in pre-trial detention. Judicial authorities should take urgent steps to address these cases including implementing human rights standards that detention before trial should be the exception and not the rule, and that anyone detained is entitled to a speedy trial or release. The Ivorian authorities should also provide defendants with the ability to appeal their conviction on questions of fact and law to ensure compliance with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights.

Finally, President Ouattara should make clear that no one convicted of serious human rights abuses will be eligible for a presidential pardon. To do otherwise would only deny victims—who have already waited nearly five years—meaningful justice.

The Role of Côte d’Ivoire’s International Partners

Côte d’Ivoire’s international partners, especially France, the United States, and the European Union, should maintain credible justice for serious crimes as a priority in the political, technical, and financial support they offer the national authorities. There are a number of steps these bilateral partners can take to support justice, including by offering or supporting opportunities to train legal professionals dealing with human rights cases related to the post-election crisis. Such support should include actors at all stages of the judicial process, including prosecutors, police, judges, defense lawyers, and those involved in witness protection.

The ICC remains a critical actor in Côte d’Ivoire. The ICC’s technical expertise behooves the court’s staff—and the ICC’s 124 member states—to find cost-neutral opportunities to share best practices when it comes to handling allegations of crimes that fall under the ICC’s jurisdiction.

The ICC’s investigation into pro-Ouattara forces also remains a vital lever in pushing for justice at a national level. While positive developments in the case against Laurent Gbagbo and Charles Blé Goudé are welcome, it remains critical that the ICC take concrete steps in its investigations of abuses by forces loyal to President Ouattara so that victims of these crimes have a path to justice.

The United Nations also has an important role to play. The UN peacekeeping mission, in operation since 2004, has provided assistance to rule of law and transitional justice efforts, and in monitoring human rights abuses and progress in the country’s courts. In 2014, as part of a long-planned drawdown of the mission from the country, the UN Security Council removed the mission’s rule of law mandate but left in place a role for monitoring human rights. The UN Security Council should maintain the mission’s role in monitoring national judicial proceedings and consolidating Côte d’Ivoire’s fragile progress on accountability.

Over the longer term, the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) should find avenues to fill the gap following the United Nations Operation in Côte d’Ivoire’s (UNOCI) departure. Notably, the Ivorian government and international donors should support the maintenance of an OHCHR mission in Côte d’Ivoire. Both OHCHR and UNDP should look for opportunities to provide technical assistance and to monitor proceedings involving allegations of grave human rights violations.

Recommendations

To the Ivorian Government, Especially the President and the Justice Minister

Strengthen Investigations and Prosecutions

- Maintain the current investigating judges in the cell for the duration of investigations into human rights crimes to avoid further delays in investigating abuses committed during the post-election conflict.

- Explore ways to provide technical support to the special cell as it conducts investigations into human rights abuses.

Bolster Judicial Independence

- Revise the Code of Criminal Procedure to provide investigating judges with direct access to the next judicial phase to determine whether a case should move to trial.

- Amend the constitution to remove the President from the head of the Conseil Superieur de la Magistrature (High Judicial Council).

- Revise the law regulating the magistrate’s profession to remove the executive’s authority over promotion, discipline and overall advancement of judges.

- Invite the UN special rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers to conduct a country visit in accordance with the terms of reference for special procedures mandate holders.

Better Protect Judges, Prosecutors, Lawyers, and Witnesses

- Move forward with a draft law for witness protection, provided the measures are consistent with a defendant’s right to a fair trial.

- Sponsor or seek assistance to train prosecutors, investigating judges, and police investigating serious international crime cases on assessing potential risks to witnesses and using discrete security measures to prevent or minimize risk.

- Provide similar trainings to judges and other courtroom staff working on serious international crimes regarding in-court measures that can be used to protect witnesses and minimize trauma.

- Provide escorts by specially trained and vetted officers for witnesses traveling to and from court, where beneficial or preferred by the witness.

- Approach third countries for the purpose of concluding relocation agreements for witnesses who cannot remain in Côte d’Ivoire because of their participation in the judicial process.

- Bolster security for judges, prosecutors, and lawyers working on serious international crime cases as a matter of priority, including by providing escorts as needed in investigations and bodyguards where there is an elevated risk of threats.

- Approach donors to obtain assistance as needed in implementing the above recommendations.

Improve Fair Trial Rights of Defendants

- Press forward on reform of the cour d’assises system, the first instance court with jurisdiction over serious crimes, to ensure compliance with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights as soon as possible. Ensure full protection for defendants’ rights to a fair trial within a reasonable time, the right to receive reasons for decisions, and a meaningful right of appeal.

- Make mandatory the provision of a lawyer for defendants in criminal cases at an earlier stage of the proceeding, as well as the provision of legal aid for indigent defendants.

Cooperate with the International Criminal Court

- Support efforts by the special cell to submit requests for assistance in investigations to the ICC under article 93(10) of the Rome Statute.

- Cooperate with the ICC’s ongoing investigations against the Ouattara side and cases currently before the court in compliance with the government’s obligations under the Rome Statute.

- Surrender Simone Gbagbo to the ICC.

To the National Assembly

- Pass legislation aimed at providing protection to witnesses inside and outside of the courtroom.

To Staff in the Special Investigative and Examination Cell, including the Procureur de la République and the Investigating Judges

- Ensure close and regular coordination between investigative judges to minimize duplication in investigations, including when approaching victims, possible witnesses and defendants.

- Seek out opportunities to strengthen working-level relationships with staff in the Office of the Prosecutor of the ICC.

To Côte d’Ivoire’s Judiciary Reviewing the Files of Defendants in Pre-Trial Detention

- Grant provisional release to all defendants in pre-trial detention still awaiting trial in relation to crimes committed during the 2010-2011 post-election crisis, unless there is concrete evidence that an individual is a flight risk, will interfere with witnesses, or poses a clear and serious danger to others.

To Côte d’Ivoire’s Government Partners, including the European Union, France, and the United States

- Support training for staff in the special cell on key issues relating to investigations and witness protection.

- Create opportunities for prosecutors, investigating judges, and judicial police investigating serious international crimes in other countries to share best practices with staff in the special cell.

- Support opportunities to promote strong working-level relationships between Ivorian judicial staff handling serious international crimes cases and the ICC, including through workshops to exchange best practices in investigations.

- Continue to prioritize the fight against impunity in political dialogue with the Ivorian authorities, reinforcing the importance of consistent government support for a special cell that can work independently and impartially.

- Ensure careful and ongoing scrutiny of judicial independence in light of the UN guidelines on judicial independence and the Principles and Guidelines on the Right to a Fair Trial and Legal Assistance in Africa.

- Grant requests from the Ivorian government to conclude relocation agreements for witnesses who need enhanced protection because of their participation in the judicial process for post-election abuses.

- Stress Côte d’Ivoire’s obligation to cooperate with the ICC, including the surrender Simone Gbagbo to The Hague.

To the United Nations Operation in Côte d’Ivoire

- Continue with private and public diplomacy pressing the government to maintain its backing for the special cell, respect the separation between the executive and the judiciary, and support fair and credible justice for post-election abuses.

- Coordinate with the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights and the United Nations Development Programme to provide technical assistance to Ivorian authorities and to monitor proceedings involving allegations of grave human rights violations, especially in light of UNOCI’s impending drawdown.

- In light of ONUCI’s impending drawdown, solicit the support of the Ivorian government and international donors for the maintenance of a United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) mission in Côte d’Ivoire.

To the United Nations Security Council

- When considering the renewal of UNOCI’s mandate, maintain a strong human rights component in the mission to monitor national judicial proceedings and help consolidate progress on accountability to date.

To the United Nations Independent Expert on the Human Rights Situation in Côte d’Ivoire

- Continue to carefully monitor progress in investigations, prosecutions, and any trials related to 2010-2011 post-election abuses to ensure they are conducted in accordance with fair trial standards.

To the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Independence of Judges and Lawyers

- Submit a request to the Ivorian government seeking a country visit in accordance with the terms of reference for special procedures mandate holders.

To the International Criminal Court, Office of the Prosecutor

- Continue to intensify investigations against perpetrators on all sides of the post-election conflict.

- Flag gaps in the capacity of the Ivorian justice system so that donors can effectively direct technical support.

- Seek out opportunities to strengthen working-level relationships with staff in the special cell, including by sharing expertise in key areas relating to investigations.

Methodology

This report is based primarily on information gathered during four research missions in Abidjan conducted by three Human Rights Watch staff between April 2014 and December 2015, this report outlines critical areas requiring additional government support so that Côte d’Ivoire can deliver credible justice for serious abuses committed during the 200-2011 crisis.

During this period, staff interviewed more than 70 people, including Ivorian government officials in the Presidency and in the Ministry of Justice; staff in the Special Investigative and Examination Cell; representatives of international and Ivorian civil society groups; United Nations officials; international experts in the field of criminal justice for serious crimes; diplomats; journalists; and donor officials. Follow-up interviews were conducted in person, by telephone, or over email between August and December 2015. Human Rights Watch did not offer interviewees any incentives for the information provided.

Many of the individuals interviewed wanted to speak candidly, but wished to retain their anonymity given the sensitivity of the issues they discussed. As a result, we have used generic descriptions of interviewees throughout the report to respect the confidentiality of these sources.

I. Background

The High Cost of Impunity

History has shown that chronic impunity has fed repeated episodes of violence in Côte d’Ivoire, underscoring that justice, in addition to giving victims the redress they deserve, is critical to achieving durable stability.

In December 1999, soldiers, disgruntled about low pay, seized power from former President Henri Konan Bédié and asked his former chief of staff, General Robert Guei, to lead the government. Although Guei’s government organized presidential elections in 2000, a controversial constitutional amendment excluded Ouattara from the election on citizenship grounds.[1]

In October 2000, once it became clear that Gbagbo was leading in the polls, Guei attempted to claim the presidency, unleashing violence that led to scores of deaths. Guei eventually fled and Gbagbo declared himself president. Ouattara immediately demanded fresh presidential elections, claiming he had been unfairly excluded, which Gbagbo refused. The bloody clashes that ensued were characterized by religious and ethnic divisions as security forces and civilians supporting President Gbagbo clashed with the mostly Muslim northerners who formed the core of Ouattara’s support. At least 200 people were killed and hundreds injured in the violence that followed the October presidential elections and, later, the December legislative elections. Those responsible were never brought to justice, beginning more than a decade of impunity.

In September 2002, an attempted coup d’état against Gbagbo’s government by northern rebel groups triggered an armed conflict in which both the Forces Nouvelles[2] rebels and Gbagbo-aligned forces committed serious human rights crimes including summary executions, indiscriminate attacks against civilians, sexual violence, and torture.

Although a May 2003 ceasefire formally ended hostilities, it left the country divided in two, with the Forces Nouvelles controlling the north and the Gbagbo government and security forces controlling the south.

No single alleged perpetrator credibly implicated in human rights violations committed during the 2002-2003 armed conflict has been convicted for their alleged crimes.[3]

Many of those from both sides who escaped prosecution for abuses were again prominent in the 2010-2011 post-election crisis, which left more than 3000 civilians dead and 150 women raped.

Elite security forces closely linked to Gbagbo dragged neighborhood political leaders from Ouattara’s coalition away from restaurants or out of their homes into waiting vehicles. Family members later found the victims’ bodies in morgues, riddled with bullets. Women who were active in mobilizing voters—or who merely wore pro-Ouattara t-shirts—were targeted and often gang-raped by armed forces and pro-Gbagbo militia groups.

Pro-Gbagbo militiamen stopped hundreds of real and perceived Ouattara supporters at checkpoints and then beat them to death with bricks, executed them by gunshot at point-blank range, or burned them alive. In the western part of the country, Gbagbo militiamen and allied Liberian mercenaries killed hundreds of people, choosing many of their victims solely on the basis of their ethnicity.

Brutal crimes were also committed by forces loyal to Ouattara, particularly after they began a military offensive in March 2011 aimed at taking control of the country. In village after village in the far west, members of the Republican Forces loyal to Ouattara killed civilians from ethnic groups associated with Gbagbo, including elderly people who were unable to flee; raped women; and burned villages to the ground. Later, during the military campaign to take over and consolidate control of Abidjan, the Republican Forces again executed scores of men from ethnic groups aligned with Gbagbo—at times in detention sites—and tortured others.

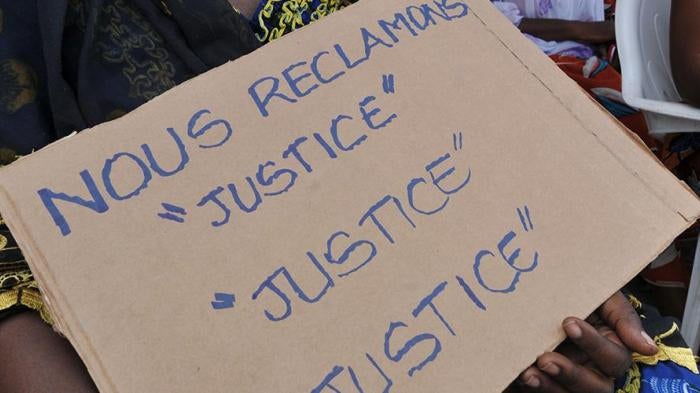

The toll of the 2010-2011 post-election violence is a stark reminder of the high cost of impunity. Victims from all sides have expressed frustration to Human Rights Watch about the lack of accountability to date for crimes committed during the post-election crisis. As one civil society actor put it, “Justice has to proceed [impartially] if there is to be reconciliation. There was the same hatred, the same animosity, in the killing done by both sides. It will reduce tension if we recognize this and see justice on both sides.”[4]

Another civil society actor put it this way, “If we remain on the path we’re currently on, we will return to where we were before. There will be another crisis...The impunity of today leads to the crimes of tomorrow.”[5]

One Ouattara supporter in Abobo who was a victim of sexual violence during the crisis told Human Rights Watch, “The people responsible for abuses must be punished. We have suffered too much.”[6] A civilian from Yopougon who voted for Gbagbo in 2010 said, “We speak about justice, but where is this justice?”[7]

In underscoring the imperative of justice, another civil society activist put it this way:

Justice reestablishes balance. It was two people who fought, not just one side. Does the fact that you won give you the right to kill people? How can reconciliation happen if justice is not impartial? That justice can’t bring peace.[8]

A Promise of Justice?

In the early days of his first term, President Ouattara vowed to change the status quo on impunity for the worst crimes. At his May 2011 inauguration, he promised that “all those that committed blood crimes will be punished” without exception.[9] Soon after, the president established a national commission of inquiry to investigate and document abuses committed during the crisis. He also created a Commission on Dialogue, Truth and Reconciliation (Commission Dialogue, Vérité et Réconciliation) to “work toward reconciliation and the reinforcement of social cohesion between all communities” by “seeking the truth on the violations committed in Côte d’Ivoire.”[10]

Finally, he created a special investigative cell (since renamed la Cellule Spêciale d’enquête et d’instruction, or the Special Investigative and Examination Cell) through an inter-ministerial order to investigate and prosecute abuses committed during the post-election crisis. Ouattara initially gave it a 12-month mandate, then renewed it to run until the end of 2013.

The creation of the special cell was a welcome development. The intermittent conflict and instability that followed the 1999 coup severely damaged the Ivorian justice system, with one international donor describing the 2000s as a “lost decade” for justice sector reform.[11] Given the challenges of rehabilitating the justice system after cycles of violence and more than a decade of neglect, identifying justice for grave crimes as a priority, and creating an institution to realize it offered hope that the government was finally willing to address Côte d’Ivoire’s deeply entrenched culture of impunity.

Serious international crimes, such as war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide, are often committed on a mass scale according to a plan or policy and are therefore more complex than other crimes.[12] Effectively investigating and prosecuting international crimes requires expertise in linking the people who pull the triggers with orders from others removed from the scene of the crime. The creation of the special cell could also potentially yield practical benefits in investigations: consolidating expertise in a specialized unit means that prosecutors, investigating judges, and judicial police are better placed to make links between crimes that would otherwise be charged separately and potentially across jurisdictions. This centralization increases the likelihood that the crimes will be effectively investigated and prosecuted.[13]

While the creation of the special cell was positive, it can only deliver results with sufficient support from the government. For much of the cell’s existence, the Ivorian government’s inconsistent backing of its work has impacted its ability to make progress.

A History of Uneven Support for the Special Cell

The initial decree creating the special cell called for three investigating judges and 20 judicial police officers to assist with investigations. In September 2012, senior justice officials under the then minister of justice told Human Rights Watch that three more investigating judges would be added to the cell, bringing the total to six, a welcome move given the scale of abuses and large number of potential cases.

Ultimately, however, the government took a different approach. Instead of enhancing the cell’s resources, under the previous justice minister, Gnemena Coulibaly, the government stripped the special cell of its staff, at one point cutting the number of judicial police officers down to four and replacing or removing investigative judges.[14] Given the complex nature of cases involving serious international crimes, the replacement of investigating judges—who then had to familiarize themselves with the underlying allegations—and reduction of investigative capacity inevitably had an impact on the cell’s ability to produce results.

The cuts appeared to reflect the government’s diminishing support for the cell. A government spokesperson announced in late 2013 that the special cell was no longer needed because the country’s justice system had been reinstated.[15] The cell’s vulnerability to executive decisions showed the disadvantage of creating the unit through an inter-ministerial order, instead of through a law promulgated by the National Assembly.

Ultimately, following intense national and international pressure to maintain the cell, on December 30, 2013, President Ouattara extended its mandate (renamed the Special Investigative and Examination Cell, la Cellule Spéciale d’enquête et d’instruction) through a presidential decree.[16] However, it took nearly six months for the government to formally reappoint staff to the cell.

The lack of formal appointment meant that the newly-placed investigating judges could not access funds needed to conduct investigations outside of Abidjan. As a result, investigating judges could not pursue allegations of crimes in western Côte d’Ivoire, the theater of many crimes committed by pro-Ouattara supporters. In the interim, a number of Ivorian and international NGOs, including Human Rights Watch, expressed concern about the government’s ostensible lack of support for the cell.[17]

Even after their formal appointment, until the fall of 2014, investigating judges in the cell had limited financial support to conduct investigations.[18] In late 2014, the UN secretary general, in a late 2014 progress report to the UN Security Council on operations in Côte d’Ivoire, said that these staffing and resource constraints “undermine[d] the government’s fight against impunity.”[19]

The breadth and open-endedness of the cell’s mandate have also been problematic. The initial mandate was to investigate crimes “relative to events in Côte d’Ivoire after December 4, 2010,” the date the crisis began.[20] The cell has divided its work into three categories of cases of crimes related to the crisis: economic crimes, crimes against the state, and human rights crimes. However, there was no clearly determined end date for the period under the cell’s consideration, and the Ministry of Justice tasked the cell with cases not directly related to the 2010-2011 post-election crisis. The resulting caseload stretched the cell’s limited resources and made it difficult for staff to focus on the human rights crimes committed during the post-election crisis.[21]

The December 2013 presidential decree renewing the cell’s mandate replicated the problem. The decree reiterated the cell’s mission to investigate crimes from the 2010 post-election crisis, but also left open the possibility of pursuing “all infractions connected or in relation to these crimes.”[22] So the special cell continued to take on cases not directly related to the human rights crimes committed during the crisis, including the 2004 disappearance of a Canadian journalist from Abidjan.[23]

Late 2014: A Shift in the Right Direction?

After years of offering tepid support for accountability, beginning in late 2014, the government began showing signs that it would give more priority to justice. In late 2014, for the first time since it began operating, and after significant pressure from national and international human rights groups and diplomats, the cell finally had the financial resources needed to conduct investigations.[24]

In July 2015, media reports suggested that the cell is continuing its investigations into alleged abuses by high-level Gbagbo supporters, and is also investigating key military officials who supported President Ouattara during the conflict.[25] Pursuing perpetrators of crimes who supported Ouattara is important to show that the government is interested in more than “victor’s justice”—a persistent criticism in light of the large number of Gbagbo supporters arrested by Ivorian authorities following the crisis, many of whom remain in pretrial detention. The perception has been further reinforced by the March 2015 conviction of Simone Gbagbo and many of ex-President Gbagbo’s former allies for crimes against the state committed during the 2010-2011 crisis.[26]

There are two factors that may help explain this shift in favor of justice: the International Criminal Court’s ongoing investigation into abuses and the recent presidential election.

In October 2011, the International Criminal Court opened an investigation in Côte d’Ivoire.[27] While initially limited to crimes committed after November 28, 2010, ICC judges extended the investigation’s reach back in time to include crimes committed after September 19, 2002, the date Côte d’Ivoire formally accepted the ICC’s jurisdiction.[28] Still, the focus of the ICC’s current investigation is on crimes committed during the 2010-2011 post-election period.

Soon after launching the investigation, the ICC issued warrants for the arrest of former President Laurent Gbagbo; a former government minister under Gbagbo and leader of the Young Patriots, a pro-Gbagbo militia, Charles Blé Goudé; and former first lady Simone Gbagbo.[29] Laurent Gbagbo and Charles Blé Goudé have been transferred to The Hague, and are currently on trial together on charges of crimes against humanity.[30]

However, Simone Gbagbo remains in Ivorian custody. The Ivorian government challenged the admissibility of her case before the ICC, stating that she is being investigated domestically for similar human rights crimes.[31] This is relevant since the ICC is a court of last resort, and only takes action when the national authorities are unable or unwilling to do so.

The ICC was not convinced. ICC judges noted that when they requested more information about the Ivorian investigation of Simone Gbagbo in August 2014, there was little activity on the case. In September and October 2014, Ivorian officials questioned Simone Gbagbo four times.[32] In October 2014, Simone Gbagbo faced a trial, although it was for crimes against the state, not human rights crimes. The trial was quickly adjourned.[33]

In December 2014, the pre-trial chamber of the ICC rejected Côte d’Ivoire’s petition, concluding:

The investigative steps into Simone Gbagbo’s criminal responsibility [for human rights crimes] are not only scarce in quantity and lacking in progression. They also appear disparate in nature and purpose to the extent that the overall factual contours of the alleged domestic investigations (as part of which these individual investigative steps were undertaken) remain indiscernible.[34]

In May 2015, the ICC dismissed the Ivorian government’s appeal of the pre-trial chamber’s decision.[35] The Ivorian government therefore remains legally obliged to surrender Simone Gbagbo to the ICC.

In late March 2015, ICC prosecutor Fatou Bensouda said that her office would push forward in its investigation of crimes committed by loyalists to President Ouattara.[36] In April, President Ouattara stated that Ivorian courts are capable of trying all cases related to the 2010-2011 post-election crisis and that he would not transfer any more suspects to the ICC.[37] Several international observers suggested to Human Rights Watch that, by finally giving the special cell the support it needs to investigate pro-Ouattara suspects domestically, the Ivorian government may be trying to strengthen the position against transferring their cases to the ICC.[38]

The lead up to the October 2015 presidential elections, too, may have contributed to the government’s renewed support for accountability. When he assumed office in 2011, President Ouattara underscored the importance of impartial justice for post-election abuses, and created the special cell, a national commission of inquiry, and a truth commission. Although the national commission of inquiry submitted its report in August 2012, recommending that the justice system hold perpetrators accountable for post-election abuses, the special cell’s effectiveness has been very limited, and victims have viewed the truth commission as largely unsuccessful.[39] Against this backdrop, some observers speculated that the recent presidential election led President Ouattara to better support the special cell to demonstrate his capacity to deliver on his promises.[40]

What Next?

The government’s recent, and long-overdue, backing for the work of the special cell is positive, but must be viewed in the context of its past feeble support for independent and impartial justice. Indeed, in mid-2015, less than a year after the special cell received the financial resources necessary to scale up its investigations, credible reports emerged that the government was pressuring the cell to prematurely finish investigations into key human rights abuses, which threatened to undermine the quality of the special cell’s work.[41]

The International Federation for Human Rights, Human Rights Watch, and 17 Ivorian nongovernmental organizations in June 2015 published an open letter to President Ouattara urging him to maintain support for the cell.[42] In response, President Ouattara reiterated that his government supports the special cell, and the minister of justice at the time echoed his statement.[43] While the investigations ultimately moved forward, these events demonstrate that the special cell’s investigations remain susceptible to executive interference.

Several international observers expressed skepticism that President Ouattara would ultimately support the trial and conviction of high-level perpetrators—some of whom retain key positions in the Ivorian military—from his side of the post-election crisis.[44] The UN’s independent expert on the human rights situation in Côte d’Ivoire, Mohammed Ayat, in May 2015 praised recent progress on justice for post-election abuses, but noted that investigations take time and resources, and cautioned that justice must operate fairly, independent of the “contingencies of the moment.”[45]

Furthermore, although trials of high-level perpetrators of human rights abuses committed during the 2010-2011 post-election crisis, would—if they take place—be a hugely positive step, it is the fairness and credibility of the proceedings that will ultimately determine whether they contribute to strengthening the rule of law and fighting impunity.

Since perpetrators of the 2010-2011 post-election abuses often acted against rival political factions, and, at times, against members of rival ethnic and religious groups, the stakes are especially high for fairly adjudicating the crimes. Supporting a justice process that is independent, impartial, based on solid evidence, and respectful of a defendant’s fair trial rights is essential for these trials to be viewed as legitimate. Indeed, credible trials are the only effective antidote to impunity.

President Ouattara said after his reelection that he remains committed to prosecuting those who committed abuses during the 2010-2011 post-election crisis, and that, “justice must be equal for all; we need to avoid impunity.”[46] Ouattara has also stated that Côte d’Ivoire’s justice system is now operational, and there is no need to surrender any more suspects to the ICC.[47]

The conduct of cases related to the crisis, which will be closely scrutinized by the ICC and the international community more broadly, will be a test of how much Côte d’Ivoire’s justice system has improved since President Ouattara came to power. Moving forward, there are a number of steps Côte d’Ivoire’s government—and its new justice minister, Sansan Kambile—can take to more effectively prioritize justice.

II. Steps to Support Credible Justice

Provide Consistent Support for Investigations

Effectively investigating cases involving multiple accused in a criminal network would be challenging for any legal system, let alone a justice system still being reconstructed. Human rights violations are even more sensitive because of the numerous victims involved, some of whom may provide testimony. The evidence provided by witnesses must be carefully managed during investigations to avoid re-traumatizing them and possible threats to their security. All of these difficulties emphasize the importance of steady support for the special cell to effectively investigate cases involving allegations of serious abuses.

The cell’ts staffing remains modest. The procureur de la république is the head of the cell, and delegates investigations to three investigating judges. The doyen among the investigating judges in the cell—that is, the judge with the most seniority—investigates human rights crimes (crimes de sang) committed during the crisis. He divides his time between the cell and a first instance court in Abidjan (Plateau). Another investigating judge is tasked with investigating crimes revealed by the national commission of inquiry report, which documented many of the grave human rights abuses committed during the crisis. There is an overlap in the scope of the investigations of two of the investigating judges.

The remaining judge is responsible for crimes against the state, economic crimes, and the killings at Nahibly in July 2012, in which members of predominantly pro-Ouattara ethnic groups, with assistance from elements of the Ivorian army, destroyed a camp for internally displaced persons, largely from the pro-Gbagbo side, killing at least eight people and injuring dozens more.[48]

In 2013, the then Minister of Justice Gnemena Coulibaly replaced the previously sitting investigating judges with the three judges currently in the cell. Unsurprisingly, the switch slowed investigations, as the new investigating judges had to essentially start from scratch to learn the files and build cases. As it is, the cell only has three investigating judges, two of whom work on human rights crimes committed during the post-election crisis. The current staff should be maintained to avoid jeopardizing the long-overdue progress on investigations.

Further, in light of the potential for overlap in investigations—since two of the three judges are presently investigating human rights violations during the post-election crisis—close coordination between judges is critical. Close and regular coordination between judges can help minimize the risk of duplicating efforts in approaching victims, possible witnesses, and defendants, especially in light of the cell’s meager staffing. Avoiding duplication is especially important when approaching victims and witnesses to prevent further traumatization and witness fatigue.

The recent trial and conviction of Simone Gbagbo also shows how important it will be to train and support the staff of the special cell to ensure the cell’s capacity to manage complicated and politically sensitive cases.

In March 2015, following a two-month trial involving nearly 80 defendants, judges of the cour d’assises—the first instance court tasked with trying serious crimes—convicted former First Lady Simone Gbagbo on charges relating to crimes against the state.[49] She was sentenced to 20 years’ imprisonment, twice as much time as the prosecution had requested.[50]

The trial was criticized byIvorian and international human rights groups, which noted a lack of rigor in the investigation, and said that convictions were obtained “on the basis of little persuasive evidence.”[51]

According to Ivorian nongovernmental organizations that monitored the trial, a number of concerns emerged about the fairness of the proceedings, some of which can be linked to weaknesses in the investigations. The observers said the court relied primarily on testimony from witnesses who often provided weak evidence or lacked credibility.[52] Very little material or documentary evidence was put forward in court to corroborate witness testimony.[53]

Further, under Ivorian law, investigating judges are required to investigate incriminating and exculpatory evidence. However, observers said that the prosecution presented very little exculpatory evidence during the proceedings, which suggested incomplete investigations.[54] Since the prosecutor only presented incriminating evidence in the trial, the NGO observers said that investigations appeared one-sided, feeding the perception that the investigating judge was biased against the accused. [55]

The monitors also said that defendants were charged with a large number of offenses across five chapters of the criminal code, and the prosecutors only identified specific charges during the course of the trial. They said that the prosecution often made only weak connections between the charges they alleged and the evidence presented. They also said prosecutors presented only limited evidence in court to connect the intellectual authors of the crimes with those who carried out the violence. [56]

The polarized political landscape in Côte d’Ivoire means that the justice system both has to be and has to appear to be fair to bolster the rule of law. In the Simone Gbagbo case, weaknesses in the investigations and the overall fair trial concerns have lent weight to efforts by Gbagbo and her supporters to publicly denounce the guilty verdict.[57]

The investigation into Simone Gbagbo’s crimes concluded in 2013, before the current investigating judges and prosecutors were working in the cell.[58] Nonetheless, the evidentiary shortcomings that emerged in Simone Gbagbo’s trial offer lessons for the cell in its ongoing investigations.

Indeed, although Simone Gbagbo was convicted of crimes against the state and related offenses, rather than for human rights abuses, investigating and prosecuting serious human rights abuses involves many of the same challenges as those encountered in the Simone Gbagbo case: understanding and untangling a complex criminal network; identifying linkage evidence; and dealing with potentially multiple accused in relation to the same set of allegations.

In light of concerns about the limited linkage evidence in the Simone Gbagbo case, the special cell should carefully consider how to best join cases involving multiple accused, as the ICC did in joining the cases of Laurent Gbagbo and Charles Blé Goudé.[59] Joining defendants in a single case is permitted under Ivorian law.[60]

The advantages of joining cases must be carefully weighed against the possible prejudice to defendants.[61] The risk of prejudice grows with the size of the case, which again highlights the need for the cell to collect evidence and build cases as strategically as possible to avoid compromising the real and perceived fairness of the trial.

Since mass human rights violations are often committed according to a plan or policy, it may prove challenging to link the intellectual authors who devised the crimes with those who pulled the trigger. Moving forward, the special cell should consider relevant modes of liability to effectively hold to account those who may be removed from the scene of the crime, such as accomplice liability. Special cell staff should also consider command responsibility under domestic and international law to effectively hold senior officials to account for crimes committed under their command. Donors should respond positively to requests for additional training on the various modes of liability as needed.

Eliminate Executive Interference in Judicial Matters

A judiciary that runs efficiently and operates independently and with impartiality is essential for the rule of law. Under international law, “everyone shall be entitled to a fair and public hearing by a competent, independent, and impartial tribunal established by law.”[62]

Independence and impartiality are especially critical when it comes to trying serious international crimes. War crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide are often committed along ethnic, religious, or political lines. In some cases, key perpetrators may continue to occupy or remain close to those in positions of power.

At the same time, the concept of judicial independence is most fragile in states recovering from conflict. It therefore remains critical to strengthen judicial independence and impartiality to show that the rule of law can more effectively address disputes than rule by violence. An independent and impartial justice system can help show that the reach of the law extends to all.

Côte d’Ivoire’s constitution recognizes a separation of power between the executive and the judiciary and guarantees the independence of the judiciary, consistent with international standards.[63] In practice, however, while there are undoubtedly individual judges who act independently, the concept of judicial independence in Côte d’Ivoire has remained fragile.

Political interference in judicial decision-making in Côte d’Ivoire predates President Ouattara’s government, and was a serious problem under former President Gbagbo.[64]

However, numerous interlocutors, including Ivorian civil society groups and diplomats, expressed concerns about what they perceive as continued executive interference in the independence of the judiciary during Ouattara’s first term. In March 2015, the UN Human Rights Committee, in its final report to the UN Human Rights Council on Côte d’Ivoire’s implementation of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), expressed concern about the judiciary’s lack of independence because of executive interference.[65]

Numerous diplomats and civil society activists said that the conduct of the 2015 trial of Simone Gbagbo together with a number of other defendants for crimes against the state raised concerns about judicial independence. A group of three Ivorian human rights groups who observed the trial concluded that the excessive sentences given to some of the accused, “lead to the conclusion that the sentences were very probably influenced by politics.”[66]

One Ivorian human rights activist said that while the independence of the judiciary is somewhat stronger than under Gbagbo’s presidency, there “remain structural problems which prevent judges from having the courage to act independently.”[67]

Under Côte d’Ivoire’s constitution, the High Judicial Council (le Conseil Superieure de la Magistrature) is supposed to in support the independence of the judiciary by governing the nomination, promotion, and discipline of judges. However, the Ivorian constitution names the head of the council as the country’s president, which does little to counter perceptions about the judiciary’s lack of independence. [68] Furthermore, the law regulating the magistrate profession also, as currently applied, allows the executive to play a key role in nominating magistrates and determining the court to which a judge is posted.[69] An international judicial expert told Human Rights Watch that this leaves judges fearing that they will be “sent to Odienné,” a particularly remote town, if they issue a ruling that displeases the executive.[70]

The French constitution has been amended to bolster the independence of its own High Judicial Council, culminating in 2008 with the removal of the president from the council.[71] The constitution of the Democratic Republic of Congo has similarly removed the president from the High Judicial Council.[72]

The criminal procedure code also creates opportunities for executive interference in the judicial process. In Côte d’Ivoire, it is the prosecutors, not the investigating judges that decide if and whether a case moves to the next judicial phase. [73] Under Ivorian law, prosecutors operate under the authority of the minister of justice.[74] As a result, key decisions regarding the fate of serious criminal cases remain vulnerable to executive influence. Other civil law systems provide the investigating judge with direct access to the next judicial phase to determine whether the case should move to trial—an important safeguard for the independence of the process. [75]

Soon after taking office, President Ouattara said that his ambition was to create a justice system that was “independent and impartial.”[76] However, his government has not finalized draft laws on the High Judicial Council and the profession of magistrates that would have increased the independence of the High Judicial Council, without requiring a constitutional amendment, by requiring the president to follow the council’s advice when selecting judges.[77]

One diplomat told Human Rights Watch that the government’s failure to make progress on these laws was “a political decision,” which reflected a “lack of desire to change the level of control that the executive currently has over judges.”[78]

Prior to the October presidential election, President Ouattara said that if re-elected, his government would propose changes to Côte d’Ivoire’s constitution.[79] His government should use the constitutional reform process to eliminate the president’s role as the head of the High Judicial Council and establish a process for appointing members of the High Judicial Council that is independent of executive influence. The government should also revise the laws on the profession of magistrates to ensure that it is the High Judicial Council, and not the executive, that determines the courts to which judges are posted.

Constitutional and legislative changes are, however, only the first step on the long road to bringing about a much-needed, long-term cultural shift towards meaningful judicial independence in Côte d’Ivoire.

Careful and ongoing scrutiny of the High Judicial Council’s operation in light of the UN guidelines on judicial independence, the Principles and Guidelines on the Right to a Fair Trial and Legal Assistance in Africa, and other guidelines, will be essential.

The mandate of the UN special rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers is especially relevant. To execute the mandate, the UN special rapporteur conducts country visits to assess the judiciary and the legal system, and, where appropriate, makes recommendations for improvements.[80] Any visit by a special procedures mandate holder should be conducted in accordance with the terms of reference for special procedures mandate holders.[81]

Protect Judges, Prosecutors, and Lawyers under Threat

People may not support justice for the most serious crimes, especially those who feel threatened, even though addressing these crimes is critical to establishing confidence in the rule of law. Some may threaten and attempt to intimidate judges and prosecutors working on sensitive cases involving allegations of serious international crimes, including war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Protecting judges from threats and harassment is essential to supporting their independence and impartiality.[82] Further, states should protect prosecutors and their families “when their personal safety is threatened as a result of the discharge of prosecutorial functions.”[83]

Developing an effective system to protect judges and prosecutors takes time and resources. An effective protection system requires the development of protocols to detect and manage threats, which may include fact-finding when threats have been made. Sharing best practices with judicial staff about how to pursue sensitive cases without triggering risks for themselves and witnesses can be instrumental to help minimize the need for more extensive protection down the road.

It may also be necessary to create a police force to provide protection to judges and prosecutors. In selecting officers, the government should carefully vet candidates to ensure they are not implicated in human rights abuses. If the Ministry of Interior or another arm of the executive has been involved in abuses, it may be necessary to create a separate police unit to preserve the unit’s independence.

In 2013, Human Rights Watch expressed concern to the Ivorian government about the lack of security provided to judges and prosecutors working in cell.[84] At this writing, there is still no form of regular protection for judicial staff.

As cases proceed against Ouattara’s supporters, the need for regular protection is even more acute. Human Rights Watch therefore urges the Ivorian authorities to make it a priority to provide adequate security to vulnerable judicial staff. This security should form part of the government’s regular budget. Donors to Côte d’Ivoire’s justice system should also positively respond to any requests for technical assistance for judicial staff on minimizing risks as they do their jobs.

Lawyers for defendants and victims of serious international crimes are just as essential to the justice process, and the possibility of threats and intimidation also extends to them. As with judges and prosecutors, states have a duty to protect lawyers “when their security is threatened as a result of discharging their functions.”[85] With respect to defense lawyers in particular, the African Commission has concluded that a defendant’s right to counsel was violated in a case where two defense teams had been “harassed into quitting the defense of the accused persons.”[86] The government should also include lawyers in the overall protection scheme.

Protect Witnesses from Threats and Reprisals

Like judicial staff, witnesses of serious international crimes are vulnerable to threats and intimidation by the subjects of criminal investigations and their supporters. States should accordingly take measures to protect victims, their families, and witnesses “before, during, and after judicial, administrative, or other proceedings that affect the interests of victims.”[87]

The Ivorian criminal code forbids the intimidation of witnesses.[88] However, Côte d’Ivoire does not have a formal or consistent approach to protecting witnesses, making investigations both difficult and potentially dangerous, as witnesses may be understandably reluctant to come forward, and those who do may be subjecting themselves to tremendous risk. Indeed, in 2012, senior Ivorian Ministry of Justice officials interviewed by Human Rights Watch acknowledged that the absence of witness protection had likely compromised the willingness of witnesses to come forward, especially victims and witnesses of crimes by pro-Ouattara forces.[89]

There is a spectrum of measures available to protect witnesses, not all of which are resource-intensive. For instance, the Ivorian government, with donor-provided technical assistance as needed, could provide training opportunities for prosecutors, investigating judges, and judicial police on best practices to assess the potential risks to witnesses and on discrete security measures to prevent or minimize their emergence.

Once proceedings are underway, witnesses who travel to and from court should be provided with police escorts by trained and vetted officers as needed. Other interim measures include introducing video-link technology to allow witnesses to testify remotely or with pseudonyms as needed in a way that is consistent with the fair trial rights of defendants.

In some limited cases, it may be necessary to indefinitely relocate witnesses outside of the country, which requires more resources and negotiation with other states to conclude relocation agreements. Côte d’Ivoire’s donor states should cooperate with efforts to conclude relocation agreements as necessary.

In late 2013, the United States Agency for International Development provided technical assistance to the Ivorian authorities to help devise a draft witness protection law, but no draft was presented for parliament’s review. The International Center for Transitional Justice held a workshop on witness protection in July 2014 with the aim of revising the law further.[90] A draft law now exists and is under review within the Ministry of Justice.[91] However, at this writing, there is still no formal law in place.

Respect the Rights of Defendants

Under international law, states should provide defendants in criminal proceedings with certain guarantees to preserve their right to a fair trial.[92] These guarantees offer protection against the arbitrary application of the law, protect individuals from abuse by the state, and help guard against injustice. Respect for a defendant’s fair trial rights is essential to ensure justice is both done and seen to be done, and is therefore a critical element of the rule of law.

Several fair trial issues deserve urgent attention if Côte d’Ivoire is to fairly try serious human rights cases related to the 2010-2011 crisis.

Under Ivorian law, the cour d’assises is the first instance court tasked with trying serious crimes. The cour d’assises is supposed to convene every three months, but in practice, it has only convened a handful of times since 2000, such as for the Simone Gbagbo trial in May 2015, because the process is cumbersome and costly.[93] For those defendants that have been in pre-trial detention since the 2010-11 post-election crisis, including many Gbagbo supporters arrested in the aftermath of the crisis, the delays in convening the cour d’assises are especially alarming, as the result is a clear violation of a defendant’s right to a trial within a timely manner under the ICCPR.[94]

Second, defendants convicted in the cour d’assises do not have a meaningful right to appeal.[95] This is contrary to article 14(5) of the ICCPR, which requires a state to review a case based on the sufficiency of the evidence and of the law, the conviction, and the sentence.[96]

Under Ivorian law, the only recourse against a decision of the cour d’assises is to lodge an appeal with the cour de cassation, the high court, based on an error of law.[97] However, a review that is limited to the formal or legal aspects of the conviction without any consideration of the facts is not sufficient under the ICCPR.[98]

Further, a convicted person can only exercise the right to have his or her conviction reviewed if he or she has access to a duly reasoned, written judgment of the first instance court.[99] The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights fair trial guidelines state that a defendant has the right to receive reasons for judicial decisions.[100] At present, under Ivorian law, judges of the cour d’assises are under no obligation to provide reasons for their decisions.

The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid bin Ra’ad stressed the urgency of developing “an effective appeals process” following the verdict in the Simone Gbagbo case.[101] Both the prosecution and Simone Gbagbo’s defense lawyer have launched appeals before the cour de cassation of the sentence meted out by the cour d’assises.[102]

In late 2012, the Ministry of Justice created a working group to address necessary reforms in the criminal code and the criminal procedure code. Côte d’Ivoire has made progress to this end: in March 2015, the national assembly adopted bills amending the Ivorian criminal code and criminal procedure code to ensure conformity of Ivorian law with the country’s international legal obligations, including the Rome Statute of the ICC.[103]

However, the Ivorian government must urgently adopt changes to ensure that defendants receive a fair trial. In 2013, with the technical assistance of UNOCI and the European Union, a recommendation emerged in the Ministry of Justice’s working group to establish a permanent criminal chamber composed of five professional judges, who would have to provide reasons for their decisions and a right of appeal.[104]

Finally, Human Rights Watch is concerned about the unavailability of legal representation for indigent defendants under the code of criminal procedure. Under the existing law, legal representation in criminal cases is only mandatory at the cour d’assises phase. The result is that indigent defendants often only receive legal aid at this late stage of proceedings, which risks compromising the quality of their representation.[105] Ivorian authorities should make legal representation mandatory at an earlier stage of the proceedings, and ensure legal aid is made available to indigent defendants accordingly.

Rule Out Pardons for Those Convicted of Serious Abuses

President Ouattara has repeatedly suggested the possibility of pardoning those who are convicted in national trials. Last year, he underscored the importance of advancing on trials, but also said he would consider invoking his authority to pardon pro-Gbagbo perpetrators after their conviction.[106] His position appears to have since evolved, first to indicate that a defendant must ask for a pardon, and more recently to state that those convicted of crimes must seek forgiveness from victims before a pardon will be considered.[107] In October 2015, President Ouattara said that, “We want justice to do its job. And then once that’s been done, our laws permit the consideration of amnesties and pardons.”[108]

Under international law, amnesties are not available for grave crimes including war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide. While the Ivorian criminal code rules out amnesties for genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes, it does not prohibit pardons.[109] The president’s power to grant pardons is set out in the constitution of Côte d’Ivoire and the criminal code.[110]

Pardons for high-level perpetrators from either side of the 2010-2011 post-election crisis would, however, deny victims—who have now waited almost five years to see perpetrators brought to account—meaningful justice. Civil society activists said that pardons for high-level perpetrators would perpetuate the cycle of impunity that has fueled Côte d’Ivoire’s past conflicts, and “would be an encouragement for recidivism by perpetrators and vengeance by victims.”[111]

Further, the ICC’s Office of the Prosecutor has made clear its position that “a sentence that is grossly or manifestly inadequate, in light of the gravity of the crimes and the form of participation of the accused, would vitiate the genuineness of a national proceeding, even if all previous stages of the proceeding had been deemed genuine.”[112]

III. The Role of International Partners

Côte d’Ivoire’s international partners have provided useful assistance to support national accountability efforts. But more will likely be needed as Côte d’Ivoire grapples with the challenges of delivering credible justice.

Assistance from Bilateral Partners

Since President Ouattara came into office, the European Union, the United States, and France have been the three largest donors to the justice sector.[113] For a period of six months beginning in late 2012, the United States Agency for International Development’s Office of Transition Initiatives (USAID/OTI) provided much-needed support to the cell’s investigative capacity. Notably, USAID funded a legal expert who was embedded in the special cell for six months and helped special cell staff manage information, identify themes, and prioritize cases.[114]

Through this project, the USAID/OTI staff developed very strong working relationships with national staff.[115] USAID/OTI discontinued the project, despite its success, in 2013.[116] The decision to discontinue support was not surprising at the time, given the government’s limited funding for the cell and the staffing cuts.

More recently, the International Center for Transitional Justice, with funding from the European Union, provided additional support to the cell. Staff from the center have worked with the special cell’s judges to create an investigative plan to better manage information, avoid duplication, and focus investigations.[117]

The EU and France have also been providing support to international and national human rights groups supporting victims of human rights abuses who are participating in proceedings as civil parties.[118]

Moving forward, further assistance may be useful to help the Ivorian justice system address the inevitable hurdles that will continue to arise in investigating and trying human rights abuses. Côte d’Ivoire should approach key donors to pinpoint areas needing enhanced technical support. Donors should respond positively and coordinate efforts to provide such support.

There are a number of ways that the Ivorian government and its key international partners can share or otherwise provide judicial officials with much-needed expertise in handling serious international crimes.

For instance, in 2010, France created a specialized war crimes unit, in part to deal with the lingering number of investigations related to the Rwandan genocide.[119] Creating opportunities for staff in the unit to share best practices with their Ivorian counterparts in the special cell could help reinforce the latter’s technical capacity.

Further, the ICC has gathered considerable information and evidence in the course of its more than four-year investigation in Côte d’Ivoire that may be relevant to the special cell, and the ICC is continuing its investigations in the country. Under the Rome Statute, to which Côte d’Ivoire is a party, states can request assistance from the ICC in domestic investigations.[120] The Ivorian authorities should support efforts by the special cell to take advantage of this valuable resource through formal requests to the ICC for assistance.

In addition, in light of the obvious overlap in their investigations, the ICC and national authorities should seek opportunities to strengthen working-level relationships; this could be realized through a specific initiative to bring relevant staff together on a regular basis. To this end, it is worth noting that France, in conjunction with the International Organization of La Francophonie, has supported training to promote cooperation between national lawyers and the ICC in the fight against impunity.[121]

National prosecutions and trials for serious international crimes are an integral part of the Rome Statute system. It would therefore be worthwhile to create opportunities for Ivorian and ICC professionals—including prosecution staff, witness protection specialists, defense lawyers, and judges—to discuss some of the practical challenges that can emerge when handling allegations of grave human rights abuses.

Côte d’Ivoire’s donors and international partners should continue to lend their political backing to the fight against impunity, emphasizing to the Ivorian authorities the importance of consistent government support for an independent and impartial justice process.

International Criminal Court

Beyond technical expertise, the Ivorian government seems keenly aware of progress in the ICC’s investigations. While positive developments in the case against Laurent Gbagbo and Charles Blé Goudé are welcome, the absence of charges against pro-Ouattara forces at the ICC, given the allegations of serious crimes by both sides, has led to a deeply polarized opinion about the ICC within Côte d’Ivoire and has undermined perceptions of the court’s legitimacy.[122]

It is vital that the ICC move forward with investigations into pro-Ouattara forces, to pursue justice for victims, to strengthen its own credibility inside Côte d’Ivoire, and to push for impartial justice at the national level.

United Nations

In 2004, the UN Security Council created the United Nations Operation in Côte d’Ivoire (UNOCI) for peacekeeping. Following the crisis after the 2010 elections, the UN Security Council revised its mandate to emphasize, among other things, technical support for the rule of law—a formidable responsibility in light of the dysfunctional justice system Gbagbo had left behind.

In its first resolution following the 2010-2011 post-election crisis, the United Nations Security Council maintained a focus on the mission’s role in assisting with the “reform of security and rule of law institutions” and supporting “efforts to promote and protect human rights.”[123] However, while the resolution, in its preamble, underscored the importance of investigating and bringing to justice those responsible for human rights abuses and welcomed “President Ouattara’s commitment in this regard,” there was no operative language in the resolution specifically referencing the mission’s role in providing assistance for this purpose.[124]

The absence of specific language is not a bar to providing assistance. Under its 2011 mandate, UNOCI used rule of law and human rights assignments to provide some logistical and technical support for national accountability efforts, including the special cell. For instance, UNOCI played a helpful role around the renewal of the special cell’s mandate, advised donors supporting the cell, and has assisted in coordinating donors active in the justice sector.[125]

However, none of the United Nations Security Council’s resolutions on Côte d’Ivoire outlined clear or immediate priorities to address the numerous challenges facing the overall justice sector. A more proactive approach by the council early on could have been beneficial. Specifically, clear language from the council directing the mission to support national accountability efforts for serious international crimes could have enhanced the mission’s technical support and political leverage to address the longstanding and deeply rooted impunity that have undermined the rule of law in Côte d’Ivoire.[126]

In 2014, as part of the long-planned drawdown of the UNOCI mission, the UN Security Council removed the justice and corrections components from the missions’ mandate, while maintaining a human rights component.[127] In light of the government’s welcome—but fragile—shift in favor of accountability, it remains critical that the UN Security Council maintain a strong human rights component in the mission to monitor national judicial proceedings and help consolidate progress to date.

Over the longer term, OHCHR and UNDP should find avenues to fill the gap following UNOCI’s departure. Notably, the Ivorian government and international donors should support the maintenance of an OHCHR mission in Côte d’Ivoire. Both OHCHR and UNDP should look for opportunities to provide much-needed technical assistance and to monitor proceedings involving allegations of grave human rights violations.

Acknowledgments