Turning Rhetoric into Reality

Accountability for Serious International Crimes in Côte d’Ivoire

Summary

As he took the oath of office on May 21, 2011, Ivorian President Alassane Ouattara faced considerable challenges, one of which was dealing with the aftermath of the brief but devastating armed conflict following the 2010 presidential elections. To realize his electoral victory, following incumbent President Laurent Gbagbo’s refusal to accept electoral results certified by the United Nations (UN), Ouattara, ultimately turned to former rebel forces for support. These forces had controlled the northern part of the country since the end of the 2002-2003 conflict which was marked by serious international crimes by both Gbagbo’s security forces and the rebels. Under the Gbagbo government, there was no accountability for these crimes.

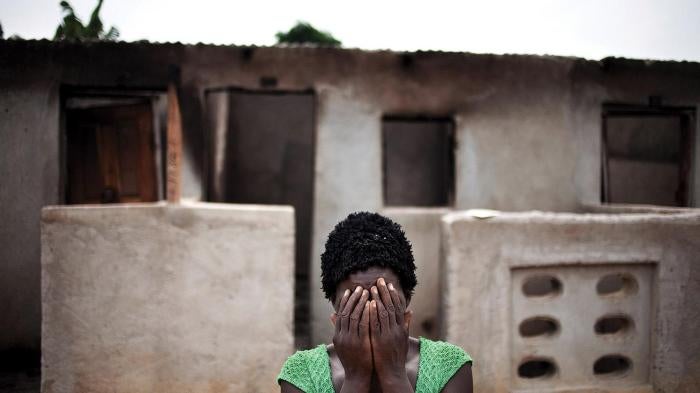

From 2003 onwards, political and military leaders on both sides implicated in overseeing atrocities retained their positions with complete impunity. By the time pro-Ouattara forces arrested Gbagbo on April 11, 2011, armed forces from both parties had, as was the case in the previous conflict, committed egregious violations of human rights and international humanitarian law. At least 3,000 people were killed and 150 women raped during the crisis, often in targeted acts perpetrated along political, ethnic, and religious lines. Since his May 2011 inauguration, President Ouattara has repeatedly underlined his commitment to hold all perpetrators of serious crimes committed during the crisis to account, including those within his own forces. To date, however, while more than 150 individuals from the Gbagbo camp have been charged with crimes stemming from the post-election crisis, not a single case has been brought against pro-Ouattara forces for atrocities committed during the five-month crisis. It remains unclear whether President Ouattara’s government will finally break from the country’s dangerous legacy of impunity for people close to the government in power.

Based on interviews in Abidjan in September 2012 and follow-up interviews with government officials, lawyers, civil society members, UN representatives, diplomats, and officials from donor agencies, this report analyzes Côte d’Ivoire’s efforts to hold perpetrators of serious international crimes during the post-election crisis to account through independent, impartial, and fair investigations, prosecutions, and trials. It builds upon Human Rights Watch’s report “They Killed Them Like it Was Nothing: The Need for Justice for Côte d’Ivoire’s Post-Election Crimes”(2011), which detailed the war crimes and likely crimes against humanity committed by both pro-Gbagbo forces and pro-Ouattara forces.

The nature and scope of the 2010-2011 violence prompted the International Criminal Court (ICC) to take action. In October 2011, the ICC judges approved the prosecutor’s request to open an investigation, the scope of which was later extended to include crimes committed since September 19, 2002. By the end of November 2011, Laurent Gbagbo, accused by the ICC of being an indirect co-author on four counts of crimes against humanity, had been arrested and transferred to The Hague, where he remains in custody. In November 2012, ICC judges unsealed an arrest warrant against the former first lady, Simone Gbagbo, for crimes against humanity, alleging that she acted as Gbagbo’s “alter ego” in overseeing atrocities in Côte d’Ivoire. At this writing, she remains in custody in Côte d’Ivoire where she has been charged with genocide, among other crimes, for acts committed during the post-election crisis. To ensure compliance with its obligations under the Rome Statute, the ICC’s founding treaty, it is incumbent on the Ivorian government to cooperate with the ICC and surrender her to the court or, as an alternative, challenge the admissibility of her case before the ICC based on national proceedings for substantively the same crimes as exist in the ICC warrant.

The Imperative for Impartial Justice

The limits on the ICC’s ability to try all serious international crime cases make national justice essential to end impunity in Côte d’Ivoire. Since the end of the post-election crisis, President Ouattara has made repeated promises that all of those involved in serious crimes—regardless of political affiliation or military rank—will be brought to justice. Chronic impunity has fed the repeated episodes of violence in Côte d’Ivoire over the last decade. Civil society actors interviewed for this report, including those who have tended to lean towards either former President Gbagbo or current President Ouattara, expressed almost unanimously that impartial justice is a necessary precondition for reconciliation, and that its continued absence will likely fuel more violence in the future.

The pursuit of accountability for serious international crimes often comes with challenges, particularly in a post-conflict situation like that in Côte d’Ivoire. Pursuing justice may prove to be deeply unpopular, including among segments of the population who believe that the forces loyal to President Ouattara who committed serious crimes were justified in doing so. Several civil society activists and a senior diplomat in Abidjan told Human Rights Watch that the one-sided approach to accountability is likely due in part to the president’s still tenuous hold over the entire military. A few government officials and diplomats expressed a need for greater stability and cited the spate of attacks on Ivorian military installations in August and September 2012, many of which were likely carried out by pro-Gbagbo militants, in justifying slow progress toward impartial accountability.

However, the country’s recent history shows that credible justice is essential to break from its repeated episodes of politico-military violence. Rather than cautioning authorities against pursuing impartial justice, the recent security threats show the urgent need to proceed in investigating and prosecuting crimes committed by both sides.

In response to the August 2012 attacks, members of the Republican Forces (Forces Républicaines de Côte d’Ivoire, FRCI), the armed forces of Côte d’Ivoire, committed widespread human rights abuses against young men from pro-Gbagbo ethnic groups, including mass arbitrary arrests, illegal detention, extortion, cruel and inhuman treatment, and, in some cases, torture. Several commanders against whom there is evidence implicating them in overseeing these abuses had been previously implicated for their command role in grave crimes during the post-election crisis. The military’s continued impunity makes it more likely that the same authors will commit the same crimes whenever there are moments of tension. In turn, the abuses have exacerbated the country’s communal divisions, reinforcing the factors that are driving the security threats in the first place.

Simply put, the cost of ignoring justice, despite the real challenges that exist, is too high.

Necessary Steps for Ivorian Authorities to Realize Impartial Justice

Following his inauguration, President Ouattara, within a short period of time, oversaw the creation of a National Commission of Inquiry; a Special Investigative Cell; and a Dialogue, Truth, and Reconciliation Commission.

The National Commission of Inquiry (Commission nationale d’enquête, CNE), which released its report in August 2012, produced a balanced summary that echoed findings from a UN-mandated international commission of inquiry and reports of human rights groups: serious international crimes were committed both by pro-Gbagbo forces and by pro-Ouattara forces. The national commission’s report offered an approximate breakdown of the cumulative human rights violations—including summary executions and acts of torture that led to death—allegedly committed by members of both groups during the crisis. Chief among its recommendations was the need to bring to justice those responsible for such violations.

The Special Investigative Cell, consisting of prosecutors, investigating judges, and judicial police, was established to investigate and prosecute crimes committed during the post-election crisis, including serious international crimes. To date, civilian and military prosecutors have collectively charged more than 150 individuals with post-election crimes. However, none of those arrested, much less charged, with violent crimes (crimes de sang) committed during the post-election crisis come from the pro-Ouattara forces. In Côte d’Ivoire’s politicized environment, the perception persists that judges and prosecutors are too easily influenced by the agenda of the executive branch of government. The lack of meaningful accountability against pro-Ouattara forces for serious international crimes committed during the crisis reinforces this perception, and underscores the growing chasm between the president’s rhetoric and reality.

The steps taken by the government to date, while important, are not enough to support the pursuit of independent and impartial justice. There are a number of areas in which the Ouattara government and Côte d’Ivoire’s international partners could provide practical assistance to put judges and prosecutors in a better position to deliver results when it comes to accountability for serious international crimes.

Strengthening Judicial and Prosecutorial Independence

Judges and prosecutors can only adjudicate cases impartially when they are able to act independently from the legislative and executive branches. Côte d’Ivoire’s constitution recognizes a separation of powers between the executive and the judiciary and guarantees the independence of the judiciary, including investigating judges. In practice, however, while there are judges that act independently, civil society activists underscored to Human Rights Watch that they are the exception rather than the rule.

The Ouattara government has taken notable steps to strengthen judicial independence. A draft law has been prepared by the High Judicial Council (le Conseil supérieur de la Magistrature, CSM)—the body governing the appointment and disciplining of judges—aimed at giving judges more say in appointing their peers. Longer-term initiatives are needed to affect a shift in culture among judges, prosecutors, and those in the executive to combat political interference and corruption. The CSM should consider ways to train judges and prosecutors about its mandate, possible threats to judicial and prosecutorial independence, and the consequences of succumbing to political interference or corruption. Officials in the executive and legislative branches should consider similar measures to sensitize political officials about why the separation of powers is essential and what should (and should not) be done to support it. Since prosecutors are legally under the authority of the minister of justice, the government, in conjunction with Ivorian prosecutors, should establish and consistently implement guidelines aimed at promoting prosecutorial independence. In addition, the government, in conjunction with Ivorian prosecutors, should develop a system of case allocation that promotes the independence and impartiality of prosecutors handling serious international crime cases.

Strengthening Prosecutions

The development and implementation of a more coherent prosecutorial strategy—one that includes criteria used by prosecutors to make decisions about case selection—is another essential part of effectively and impartially addressing serious international crimes. To start, the Special Investigative Cell, with government and donor support as needed, should consider building on the work of the National Commission of Inquiry and conduct a mapping exercise to develop a comprehensive list of the crimes committed by region during the crisis, pinpointing individual suspects where possible. Such a mapping could help identify specific priorities for the office based on the scale of violations, patterns of violence, and leads or sources of evidence, including potential perpetrators. Non-confidential portions of both the mapping exercise and the prosecutorial strategy should be shared with the public to increase understanding about the office’s work and to build trust in its ability to execute its mandate independently and impartially.

To further facilitate the development of a meaningful prosecutorial strategy, the ICC’s Office of the Prosecutor (OTP) should share its analysis of the conflict and other non-confidential materials with staff in the Special Investigative Cell. While this information may be derived from public sources, the analysis could be of significant value to the procureur de la république and the investigating judges with less experience in handling serious international crimes.

There are also a number of steps Ivorian authorities can take to support domestic investigations. Under Ivorian law, investigating judges are the primary investigators of allegations of criminal conduct, with the assistance of the judicial police as needed. The modest staffing of the Special Investigative Cell—only three investigating judges at present—seems insufficient to address the large number of criminal allegations stemming from the post-election period. The previous minister of justice indicated that the ministry would appoint three additional investigating judges; the current minister of justice should do so as soon as possible.

Field investigations are essential and should be intensified, especially since many victims and witnesses are scattered across the country and cannot easily travel to Abidjan to give a statement. But in addition to traveling outside Abidjan, investigating judges and judicial police must be able to cultivate confidence in communities affected by crimes, especially those committed by the Republican Forces. Steps to take in doing this include: recruiting judicial police from all communities affected by the post-election crisis where the crimes being investigated were committed, training investigating judges and judicial police on how to assess the risk to victims and witnesses, and devising ways to approach victims that do not compromise their safety or cause further trauma.

Legal Reforms to Improve Fair Trial Rights of Defendants

Respect for the rights of the accused ensures that judicial processes are, and appear to be, fair and credible. In Côte d’Ivoire, a number of fair trial concerns relate to the jurisdiction of serious crimes, including serious international crimes, under the cour d’assises— a non-permanent court composed of a president, two professional judges, and nine lay jurors, including three alternates. First, while the cour d’assises is by law supposed to sit every three months, it has only been convened twice since 2000, in large part because the process is cumbersome and costly. While it may be possible to convene the cour d’assises for a handful of high-profile cases, the majority of defendants already in custody for post-election crimes appear likely to remain in pretrial detention until the issue of the cour d’assises is resolved, violating their right to be tried within a reasonable time. Further, decisions by the cour d’assises are not subject to appeal, violating a defendant’s right under international human rights law to have his conviction and sentence reviewed by a higher tribunal.

The Ministry of Justice has notably identified the reform of the Code of Criminal Procedure as a priority and formed a working group in late 2012 to address the issues related to the cour d’assises. The creation of a working group is a welcome development, and the group should reach a resolution on these issues as soon as possible.

In addition, under the Code of Criminal Procedure, legal representation for defendants in criminal cases is only mandatory at the cour d’assises phase, which also means that indigent defendants only have access to legal aid at this late stage of proceedings. This risks compromising the quality of representation provided, which is especially problematic in complex cases involving serious international crimes. Ivorian authorities should make mandatory at an earlier stage of the proceeding the provision of a lawyer for defendants in criminal cases and legal aid for those who are indigent.

Establishing a Framework for Witness Protection and Support

Trials of serious crimes can be extremely sensitive and create risks to the safety and security of witnesses and victims who may testify to deeply traumatic events. Identifying and implementing a strategy for witness protection will be crucial in convincing victims and witnesses, particularly of crimes committed by pro-Ouattara forces, that they can bring complaints.

In the short term, the government, with support from donors as necessary, should sponsor training workshops for prosecutors, investigating judges, and police investigating serious international crime cases to support the protection of witnesses. Such training could cover how to assess potential risks to witnesses and how to use discrete security measures to prevent or minimize such risks. Similar training should be provided to judges and other courtroom staff working on serious international crimes regarding in-court measures that can be used to protect witnesses and minimize trauma. Ivorian authorities should also consider establishing a safe house for witnesses facing temporary threats to their safety.

Over the longer term, Ivorian authorities should establish a law(s) to create a system to protect witnesses. In devising such a law(s), Ivorian authorities should consider creating a neutral witness protection unit—meaning it operates for all witnesses, regardless of if they are testifying on behalf of the prosecution or defense, and can enter into relocation agreements with third countries to protect witnesses in extreme circumstances. The benefits of such a unit potentially extend well beyond managing witnesses in cases of serious international crimes and could include other sensitive or high profile cases.

Providing Security for Judges, Prosecutors, and Defense Lawyers

Judges and prosecutors cannot work independently or impartially if they fear for their safety. The risk of retribution is even greater for judges and prosecutors involved in serious international crime cases, given the gravity and sensitive nature of the underlying crimes. At present, there is no dedicated force to provide protection to judges and prosecutors. The government should bolster security for judges and prosecutors as a matter of priority. Ministry of Justice officials should also consider providing protection as needed for defense attorneys working on serious international crime cases; given the sensitivity of the crimes involved, they are likely to receive threats that could compromise the representation of their clients.

Necessary Steps for International Partners

While Côte d’Ivoire’s international partners have poured money into an array of rule of law projects, their commitment to help Ivorian authorities pursue accountability for serious international crimes has been inconsistent over the last decade. Greater financial and diplomatic support for judicial efforts to handle serious international crimes—including by using funds already designated for rule of law projects to more clearly support the prosecution, trial, and defense of these crimes—could assist Côte d’Ivoire in addressing its dangerous legacy of impunity.

Putting Complementarity into Practice: Building Capacity to Try Serious Crimes

The complementarity principle under the Rome Statute puts responsibility for pursuing justice for serious international crimes squarely on the shoulder of states, with the ICC only intervening as a court of last resort. There has been growing recognition within the European Union (EU), the ICC’s Assembly of States Parties, and the UN, that international partners—including key donor states and the intergovernmental organizations themselves—should use funds designated for rule of law reform projects to more specifically strengthen capacity of national institutions to realize justice for international crimes.

While progress on complementarity in diplomatic circles is welcome, it must be matched by concrete advances on the ground. Experience to date in Côte d’Ivoire reveals that while key donor states and intergovernmental organizations like the EU and the UN have invested significant resources in rule of law reform, support specifically for efforts to pursue justice for serious international crimes has been more limited.

The challenge for the donor community is to capitalize on the Ivorian government’s expression of will and square it with their commitments to complementarity made at the policy level. Côte d’Ivoire’s international partners should think proactively about how assistance designated for justice sector reform could be more specifically targeted to support efforts aimed at bringing to justice and defending perpetrators of serious international crimes. Donors should consult with national authorities to determine how this additional support could be used.

ICC staff can also help by flagging gaps in capacity so that donor support is directed to best effect. Further, during planned missions to Côte d’Ivoire in relation to ICC activities, ICC staff could seek out low-cost or cost-neutral opportunities to provide Ivorian authorities informal training or workshops in areas where weaknesses have been identified, such as witness protection.

Increasing Private and Public Diplomacy

Côte d’Ivoire’s international partners, through private and public diplomacy, have an important role to play in encouraging a political climate that favors independent and impartial justice. Several diplomats and UN officials told Human Rights Watch that they have consistently engaged in private diplomacy on these issues, which is important. However, given the lack of progress toward impartial justice to date, donors should increasingly through their private and public statements put pressure on the government to address issues that impede credible, impartial investigations, prosecutions, and trials, including in the areas identified in this report. Concerted action aimed at helping the Ouattara government end the impunity and divisiveness that defined the Gbagbo era can help avoid a recurrence of large-scale violence. Côte d’Ivoire’s international partners should also continue to emphasize with the government the need to comply with its obligation to cooperate with the ICC in its existing cases—including that of Simone Gbagbo—and its ongoing investigations.

The International Criminal Court

Despite ample evidence of crimes committed by pro-Ouattara forces that fall under the ICC’s jurisdiction, the ICC has only made arrest warrants public against the former president and his wife, Simone. This reflects the Office of the Prosecutor’s decision to pursue a “sequential” approach—meaning it will conclude its investigations against the Gbagbo side before moving on to pro-Ouattara forces.

The OTP has frequently indicated that its investigations are impartial and ongoing. However, as more time has passed without action against anyone from the Ouattara camp, many Ivorians, including Ivorian civil society leaders, have increasingly viewed the ICC as “playing politics” in Côte d’Ivoire and treading lightly around the Ouattara government. In addition to compromising the ICC’s credibility among many Ivorians, the sequencing approach has been mimicked by Ivorian authorities, which has fueled rather than eased tensions.

As the ICC Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda continues investigations in Côte d’Ivoire, she should ensure that cases against individuals from the pro-Ouattara forces are investigated as robustly as those from the Gbagbo side, including seeking from the court’s judges additional arrest warrants where evidence is gathered against those responsible for crimes in the court’s jurisdiction. Indeed, the fact that the ICC is a court of last resort when governments are either unwilling or unable to pursue cases only underscores the imperative of ICC action against those on the Ouattara side who are otherwise beyond the reach of justice. Concrete action against pro-Ouattara individuals where there is evidence of ICC crimes would go a long way toward rehabilitating the ICC’s credibility in Côte d’Ivoire as an impartial institution, and could help create the space for Ivorian authorities to similarly make much-needed progress toward ensuring that all victims have access to justice.

Recommendations

To the Ivorian Government, Particularly the President and the Justice Minister

Bolster Judicial and Prosecutorial Independence

- Finalize and work to pass the draft law on the High Judicial Council (le Conseil supérieur de la Magistrature, CSM) designed to give judges more influence in appointing new judges.

- Ensure sanctions against political officials who try to interfere with the work of prosecutors or judges working on serious international crime cases.

- Make clear publicly and privately that the executive supports the Special Investigative Cell in pursuing post-election crimes committed by both sides. Emphasize that prosecutors and judges will not face negative consequences for pursuing perpetrators linked to the government.

- In collaboration with the procureur général and the procureur de la république, develop and consistently implement guidelines aimed at supporting prosecutorial independence.

- Consider establishing a section of the CSM that would manage, among other things, the appointment and dismissal of prosecutors.

- Consider engaging the mandate of the UN special rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers.

Strengthen Prosecutions and Investigations

- Appoint without delay additional staff, including investigating judges, to the Special Investigative Cell.

- Approve plans to embed additional independent legal experts in the Special Investigative Cell.

- Hold regular meetings with staff in the Special Investigative Cell aimed at improving the office’s effectiveness, particularly in supporting underfunded or understaffed areas of the cell and in identifying ways to better engage with victims from both sides of the crisis.

- Request from the Ministries of Interior and Defense the appointment to the Special Investigative Cell of judicial police officers from all communities affected by the post-election crisis.

- Finalize a platform to enable information sharing and coordination between all of the transitional justice institutions, including the Special Investigative Cell and the Dialogue, Truth, and Reconciliation Commission.

Improve Fair Trial Rights of Defendants

- In reforming the cour d’assises, ensure that defendants’ rights to a fair trial within a reasonable time and to an appeal are fully protected as soon as possible.

- Make the provision of a lawyer for defendants in criminal cases mandatory at an earlier stage of the proceeding, as well as the provision of legal aid for indigent defendants.

Better Protect Witnesses, Judges, Prosecutors, and Defense Lawyers

- Sponsor trainings for prosecutors, investigating judges, and police investigating serious international crime cases on how to assess the potential risks to witnesses and how to use discrete security measures to prevent or minimize risk. Provide similar trainings to judges and other courtroom staff working on serious international crimes regarding in-court measures that can be used to protect witnesses and minimize trauma.

- Provide police escorts by specially trained and vetted officers for witnesses traveling to and from court, where beneficial or preferred by the witness.

- Establish safe houses for witnesses facing temporary threats to their safety.

- Devise a draft law(s) for witness protection that provides safeguards inside and outside of the courtroom, and which are consistent with a defendant’s right to a fair trial.

- Consider creating a neutral witness protection unit, which should have operational autonomy to minimize the disclosure of information about witnesses and the authority to facilitate the relocation of witnesses to third countries as needed.

- Bolster security for judges, prosecutors, and defense lawyers working on serious international crime cases as a matter of priority, including by providing escorts as needed in investigations and bodyguards where there is an elevated risk of threats.

- Consider vesting the authority to oversee trials of serious international crime cases with a limited number of judges, as has been done with prosecutors and investigating judges in the Special Investigative Cell, in order to facilitate the protection of judges and to better ensure sufficient expertise in dealing with likely complicated and politicized cases.

- Approach donors to obtain assistance as needed in implementing the above recommendations and to improve the overall capacity of those handling serious international crime cases, including defense attorneys.

Cooperation with the International Criminal Court

- Cooperate with the ICC’s ongoing investigations and cases in Côte d’Ivoire, including in the Simone Gbagbo case, in compliance with the government’s obligations under the Rome Statute.

To the National Assembly

- Pass a law that reaffirms the Special Investigative Cell’s authority to investigate and prosecute crimes, including violent crimes, committed throughout the country during the post-election crisis.

- Pass legislation aimed at providing protection to witnesses inside and outside of the courtroom, while also safeguarding a defendant’s right to a fair trial.

To the High Judicial Council (Conseil Supérieur de la Magistrature)

- Consider ways to sensitize judges and prosecutors, such as through workshops or other training seminars, about the council’s mandate, possible threats to judicial and prosecutorial independence, and the consequences of succumbing to political interference or corruption.

- In coordination with the inspector general, investigate allegations of corruption involving judges and prosecutors and ensure that those who are credibly implicated are appropriately sanctioned.

To Staff in the Special Investigative Cell, Including the Procureur de la République and the Investigating Judges

- Move forward with plans to conduct a mapping exercise to develop a comprehensive list of serious crimes committed by region during the post-election period and to pinpoint suspects where possible, in order to provide the basis for identifying more specific priorities for the office.

- Develop a more comprehensive prosecutorial strategy that includes criteria used by prosecutors to make decisions about case selection.

- Publish non-confidential portions of any future mapping exercise or prosecutorial strategy to increase understanding about the Special Investigative Cell’s work and to build trust in its ability to execute its mandate independently and impartially.

- Intensify field investigations, especially since many victims and witnesses are scattered across the country and cannot easily travel to Abidjan.

- Seek training for investigating judges and judicial police on assessing security risks to victims and witnesses and approaching them in a manner that does not compromise their safety or cause further trauma.

- Consider designating an additional investigative team to coordinate and pursue linkage evidence, meaning evidence linking the “trigger pullers” on the ground with those who gave the orders across all regions, seeking additional resources from the Ministry of Justice as needed.

- Use the Rome Statute definitions of crimes and modes of liability when doing so would extend the reach of justice, including for crimes committed after September 2002.

To the Ministries of Interior and Defense

- Consider favorably requests from the Ministry of Justice to appoint to the Special Investigative Cell judicial police officers from all communities affected by the post-election crisis.

To the United Nations and Intergovernmental and Government Partners (including the European Union, the United Nations Development Program, the United Nations Operation in Côte d’Ivoire, France, and the United States)

- In consultation with national authorities, think specifically about how assistance designated for justice sector reform could be better targeted to support efforts aimed at bringing to justice and defending perpetrators of serious international crimes. For instance, donors that have allocated funds for training judicial personnel could direct some of this support to provide practical training to prosecutors and judges handling violent crimes committed during the crisis.

- Increase private and public diplomacy to press the government to better support prosecutors and judges in pursuing impartial justice in fair and credible trials, and to continue cooperation with the ICC in its cases and ongoing investigations.

To the United States

- Continue with plans to embed independent legal experts in the Special Investigative Cell.

To the United Nations Secretary-General

- Note with concern the absence of impartial accountability and highlight obstacles linked to this ongoing failure in public reports to the UN Security Council.

To the United Nations Independent Expert on the Human Rights Situation in Côte d’Ivoire

- Monitor and highlight obstacles that may compromise the independence and impartiality of judges and prosecutors, especially in relation to serious international crime cases. Continue monitoring and reporting on the Ivorian government’s progress in the implementation of your recommendations in regards to justice for serious international crimes.

To the International Criminal Court

Office of the Prosecutor

- Continue investigations in Côte d’Ivoire against all sides of the conflict with a view to requesting the court’s judges to issue additional arrest warrants, evidence permitting, against individuals from the pro-Ouattara forces responsible for crimes in the court’s jurisdiction.

- Flag gaps in the Ivorian justice system’s capacity so that donor support can be directed to best effect.

- During planned field missions to execute the ICC’s mandate under the Rome Statute, seek out low-cost or cost-neutral opportunities to provide informal training or workshops for Ivorian authorities in areas where weaknesses have been identified, such as witness protection.

- Share with Ivorian authorities the ICC’s analysis of the conflict and other non-confidential materials, in order to help facilitate national-level investigations and prosecutions.

Registry

- Continue with plans to open a field office in Abidjan as soon as possible.

- Authorize field staff to travel outside Abidjan—including to refugee camps in Liberia, for instance—to disseminate information about the court’s mandate, get a sense of the key information gaps that exist, and develop a longer-term outreach and communications strategy that addresses real needs.

Methodology

This report is based primarily on research conducted by two Human Rights Watch staff in Abidjan between September 8 and September 14, 2012.

During the mission, staff conducted approximately 30 interviews with Ivorian government officials, including in the Justice Ministry; legal practitioners, including staff in the Special Investigative Cell and criminal defense lawyers; representatives from a wide range of civil society groups; United Nations officials; diplomats; donor officials; and journalists.

Between October 2012 and February 2013, Human Rights Watch staff conducted additional interviews in person, by telephone, or over email with diplomats, UN officials, International Criminal Court officials, an international expert with knowledge of Côte d’Ivoire’s justice system, and representatives of civil society.

Many of the individuals we interviewed wanted to speak candidly, but did not wish to be cited by name given the sensitivity of the issues concerned. As a result, we have used generic descriptions of interviewees throughout the report to respect the confidentiality of these sources.

I. Background

As he took the oath of office on May 21, 2011, President Alassane Ouattara faced considerable challenges, including dealing with the aftermath of a brief but devastating armed conflict in which heinous crimes had been committed against civilians. Following the refusal of incumbent President Laurent Gbagbo to accept electoral results widely considered free and fair, and certified by the United Nations, Ouattara ultimately turned to former rebel forces for support. These rebel forces had controlled the northern part of the country since the end of the 2002-2003 conflict, which was marked by serious international crimes by both Gbagbo’s security forces and the rebels. Under the Gbagbo government (2000 to 2010), there was no accountability for these crimes.

On both sides, political and military leaders implicated in overseeing atrocities retained their positions with complete impunity. By the time pro-Ouattara forces arrested Gbagbo on April 11, 2011, armed forces on both sides had again committed egregious violations of human rights and international humanitarian law. Twenty-two months after President Ouattara’s May 2011 inauguration, it remains unclear whether his government will finally break from the country’s dangerous legacy of impunity.

Armed Conflict and Political-Military Stalemate, 2002-2007

On September 19, 2002, a rebel group known as the Patriotic Movement of Côte d’Ivoire(Mouvement Patriotique de Côte d’Ivoire, MPCI) launched attacks against strategic targets in Abidjan and against the northern towns of Bouaké and Korhogo.[1] Joined by two armed groups in the western part of the country,[2] the rebels quickly controlled the northern half of Côte d’Ivoire. The three groups formed a political-military alliance known as the Forces Nouvelles, or New Forces, demanding new elections and the removal of President Laurent Gbagbo, whose presidency they perceived as illegitimate due to flaws in the 2000 elections;[3] and an end to the political exclusion and discrimination against northern Ivorians.[4]

Gbagbo’s security forces responded to the rebel attacks by descending on low-income neighborhoods in Abidjan occupied primarily by immigrants and northern Ivorians. Although they carried out these operations for the stated purpose of searching for weapons and rebels, the security forces often simply ordered out all residents and burned or demolished their homes. In displacing over 12,000 people, the security forces carried out numerous human rights abuses, including arbitrary arrests and detentions, summary executions, rape, and enforced disappearances. [5] For their part in the north, the MPCI rebel group summarily executed at least 40 unarmed gendarmes and 30 of their family members in Bouaké between October 6 and 8, 2002; although the number of security forces executed in this event was particularly high, the killing of captured Gbagbo security forces would continue throughout the conflict. [6]

In subsequent months, armed clashes broke out between the two fighting forces. Fighting was particularly intense in the country’s west, where both sides recruited Liberian mercenaries; militia groups, often referred to as community self-defense groups, also fought with Gbagbo’s security forces. [7]

Throughout the conflict, government security forces and the Forces Nouvelles frequently attacked civilian populations perceived to support the other side. Human Rights Watch documented grave crimes committed by all sides, including summary executions, massacres, targeted sexual violence, indiscriminate helicopter attacks, and arbitrary arrests and detention by Gbagbo’s security forces; state-supported violence, including killings, by pro-Gbagbo militia groups; and summary executions, massacres, targeted sexual violence, and torture by the Forces Nouvelles. [8] Both sides recruited Liberian mercenaries who committed large-scale killings of civilians, and both sides used child soldiers. [9]

In May 2003 a ceasefire agreement formally ended active hostilities between the government and the Forces Nouvelles, though occasional breaches of the ceasefire continued through 2005. The country was split in two—as it would remain through 2010—with the Forces Nouvelles controlling the north and the Gbagbo government and security forces controlling the south. Severe human rights violations against civilian populations continued in both parts of the country. On March 25, 2004, Gbagbo’s security forces indiscriminately killed more than 100 civilians in response to a planned march by opposition groups; some 20 more people were victims of enforced disappearances.[10]Violent, pro-Gbagbo militia groups including the Student Federation of Côte d'Ivoire (Fédération Estudiantine et Scolaire de Côte d'Ivoire , FESCI) and the Young Patriots (Jeunes Patriotes) supported security forces in intimidating, extorting, and committing acts of violence against northerners, immigrants, and other people perceived to support the opposition.[11] In the Forces Nouvelles-controlled north, commanders became exceedingly wealthy through extortion and racketeering; with no judicial system there, arbitrary detention, torture, and extrajudicial executions continued against perceived supporters of the Gbagbo government.[12] Sexual violence against women and girls remained widespread in both parts of the country. Armed forces and civilians terrorized women, who found themselves without effective state response due to weak legal and security institutions that failed to prevent violence, prosecute perpetrators, or support victims.[13]

No Truth, No Justice under Gbagbo Government

No one was brought to justice for any of the grave crimes committed during the 2002-2003 armed conflict and its aftermath. Despite clear links between the deep-rooted impunity among the armed groups and the widespread atrocities, the Gbagbo government never prioritized accountability. On April 18, 2003, the Gbagbo government formally accepted the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court (ICC) “for the purposes of identifying, investigating and trying the perpetrators and accomplices of acts committed on Ivorian territory since the events of 19 September 2002.” [14] Yet in subsequent years, once it became apparent that the ICC would be investigating crimes by pro-Gbagbo forces as well as by the Forces Nouvelles, the government consistently prevented the ICC from visiting Côte d’Ivoire to perform preliminary investigations. [15]

Although the Gbagbo government bore primary responsibility for the failure to ensure accountability, the inconsistent approach of Côte d’Ivoire’s international partners to justice for serious crimes in violation of international law also undermined its pursuit during this period. In 2004 the United Nations created an international commission of inquiry to investigate the crimes committed during the 2002-2003 conflict. However, after six months of field investigations and drafting, the UN Security Council buried the commission’s report; at this writing, the report is still unpublished, although a leaked version is accessible online. The report included an annex with a list of 95 people deemed most responsible for serious crimes, along with specific allegations against them. Radio France Internationale reported that the annex implicated high-level political and military leaders on both sides.[16] The list has never been made public, and the Security Council has not used it to pressure Ivorian authorities to ensure credible domestic investigations and prosecutions. Top UN officials, along with powerful countries on the Security Council, apparently deemed justice at odds with establishing peace in Côte d’Ivoire.

With no justice after the 2002-2003 armed conflict, key political and military leaders on both sides of the politico-military divide, some of whom had overseen serious crimes, remained in command positions as Côte d’Ivoire moved toward the 2010 presidential elections. The aftermath of the elections, which pitted Laurent Gbagbo against his longtime rival, Alassane Ouattara, would again expose the country’s deep political and ethnic fissures and the consequence of longstanding impunity.

Post-Election Violence, November 2010-May 2011

After five years of postponing presidential elections, Ivorians went to the polls on November 28, 2010 to vote in a run-off between incumbent President Gbagbo and former Prime Minister Ouattara. After the Independent Electoral Commission announced Ouattara the winner with 54.1 percent of the vote—a result certified by the UN Operation in Côte d’Ivoire (UNOCI)—Gbagbo refused to step down. [17] Five months of violence followed, in which at least 3,000 civilians were killed and more than 150 women raped, often in attacks perpetrated along political, ethnic, and religious lines.

During the first three months of the post-election crisis, the vast majority of abuses were carried out by security forces and militia groups under Gbagbo’s command. Elite security force units closely linked to Gbagbo abducted neighborhood political leaders from Ouattara’s coalition, dragging them away from restaurants or out of their homes into waiting vehicles. Family members later found the victims’ bodies in morgues, riddled with bullets. Pro-Gbagbo militias manning informal checkpoints throughout Abidjan murdered scores of real or perceived Ouattara supporters, beating them to death with bricks, executing them by gunshot at point-blank range, or burning them alive. Women active in mobilizing voters—or who merely wore pro-Ouattara t-shirts—were targeted and often gang raped by armed forces and pro-Gbagbo militia groups. [18]

As international pressure increased on Gbagbo to step down, the violence intensified. The Gbagbo government-controlled state television station, Radiodiffusion Télévision Ivoirienne (RTI), incited violence against pro-Ouattara groups and exhorted followers to set up roadblocks and “denounce all foreigners.” [19] Hundreds of northern Ivorians and West African immigrants were killed in Abidjan and western Côte d’Ivoire between February and April, sometimes solely on the basis of their name or dress. Mosques and Muslim religious leaders were likewise targeted. Among the worst incidents, Gbagbo’s security forces opened fire on women carrying out a peaceful march and launched mortars into heavily populated Abidjan neighborhoods, killing dozens. [20]

Pro-Ouattara forces launched a military offensive in March 2011 to take control of the country and, as the crisis shifted to full-scale armed conflict, they were likewise implicated in atrocities. President Ouattara signed a decree on March 17, 2011 creating the Republican Forces of Côte d’Ivoire (Forces Républicaines de Côte d’Ivoire, FRCI), comprised primarily at the time of members of the former Forces Nouvelles rebel group. In village after village in western Côte d’Ivoire, particularly between Toulepleu and Guiglo, members of the Republican Forces killed civilians from pro-Gbagbo ethnic groups, including elderly people who were unable to flee; raped women; and burned villages to the ground. In Duékoué, pro-Ouattara forces massacred several hundred people, pulling unarmed men they alleged to be pro-Gbagbo militia members out of their homes and executing them.[21]

Later, during the military campaign to take over and consolidate control of Abidjan, the Republican Forces again executed scores of men from ethnic groups aligned to Gbagbo—at times in detention sites—and tortured others. [22]

By conflict’s end in May 2011, both sides had committed war crimes and likely crimes against humanity, as documented by a UN-mandated international commission of inquiry and human rights organizations. [23] In August 2012 a National Commission of Inquiry created by President Ouattara published a report likewise documenting hundreds of summary executions and other crimes by both sides’ armed forces. [24]

Although the scale of serious human rights abuses has decreased since the end of the post-election conflict, the Republican Forces have continued to engage in arbitrary arrests and detention, extortion, inhuman treatment, and, in some cases, torture, through at least September 2012. [25]

II. Accountability for Post-Election Crimes to Date

National Accountability Initiatives

Since the end of the post-election crisis, President Ouattara has repeatedly promised that all of those involved in serious crimes—regardless of political affiliation or military rank—will be brought to justice. [26] After his inauguration in May 2011, the president swiftly created institutions tasked with providing truth and justice for the post-election crisis. In short order, he established a National Commission of Inquiry (Commission nationale d’enquête, CNE, created June 15, 2011), a Special Investigative Cell (Cellule spéciale d’enquête, created June 24, 2011), and a Dialogue, Truth, and Reconciliation Commission (Commission dialogue, vérité et réconciliation, created July 13, 2011), each of which will be discussed in more detail below. The military justice system is also handling cases in relation to the post-election crisis.

In a January 2012 interview with Le Monde and during an April 2012 visit to western Côte d’Ivoire, Ouattara assured his presidency would be defined by “even-handed justice” and an end to impunity, which he referred to as the country’s “tragedy.”[27]Yet, 22 months after the conflict’s end, Ivorian authorities have only arrested or charged individuals from the Gbagbo camp with crimes related to the post-election crisis.Without swift and determined action, Ouattara’s government is in danger of continuing the country’s principal “tragedy”: impunity for those connected to power.

National Commission of Inquiry

The National Commission of Inquiry was established on the heels of a report published by an international commission of inquiry, created under the authority of the UN Human Rights Council in March 2011 at the request of President Ouattara’s government.[28] The international commission of inquiry’s report, presented at the 16th session of the Human Rights Council on June 15, 2011, concluded that many serious violations of human rights and international humanitarian law were committed by all sides to the conflict.[29] Chief among its recommendations was the need to bring those responsible for such violations to justice.[30]

The National Commission of Inquiry began its field work in January 2012 with the mandate of investigating alleged violations of human rights and international humanitarian law during the post-election crisis.[31] It was established as an administrative, not a judicial, commission, meaning it did not focus on pinpointing individual criminal responsibility.[32] Even before its findings were released, President Ouattara cited the commission’s work as evidence of his commitment to impartiality and promised to ensure that any person implicated in the commission’s report would be subject to judicial investigation.[33] President Ouattara initially indicated that the commission would complete its work in late February or early March, sparking concerns that the commission may not have the time or necessary independence to fulfill its mandate.[34] The mandate was ultimately extended and the commission released a public summary of its report in August 2012; a confidential annex was sent to the prime minister and the minister of justice.

A comprehensive analysis of the commission’s summary is beyond the scope of this report. However, one of the commission’s most significant findings is that crimes were committed both by forces loyal to Gbagbo and by forces loyal to Ouattara. It also offers an approximate breakdown of the cumulative human rights violations—including summary executions and acts of torture that led to death—allegedly committed by these groups during the crisis.[35]

The National Commission of Inquiry’s work emphasizes the need for impartial justice. In discussing the commission’s report, the minister of justice, human rights, and public liberties, Gnénéma Coulibaly, told Human Rights Watch, ‘“No one can say [now] … that only one side is responsible for [abuses]. Every side is responsible and every side needs to admit their level of responsibility.” [36] The need to open judicial investigations against those suspected of committing the violations outlined in the report, regardless of political affiliation, was one of the commission’s key recommendations. [37] Both the current minister of justice and a civil society activist interviewed by Human Rights Watch felt that, since it was produced by a national body, the commission’s report helped depoliticize the idea that both sides had committed egregious crimes, which could pave the way for progress in judicial investigations. [38]

Special Investigative Cell

The Special Investigative Cell was created by the government through an interministerial order in response to the number of crimes committed during the crisis and the reality that the courts were not yet functioning in the crisis’s immediate aftermath.[39] The Special Investigative Cell is attached to the tribunal of first instance in Abidjan and is tasked with conducting criminal investigations in relation to events in Côte d’Ivoire since December 4, 2010.[40] It handles three categories of cases stemming from the crisis: attacks against state security, economic crimes, and violent crimes. It consists of one procureur de la république, three deputy prosecutors, and three investigating judges; senior officials under the previous minister of justice said three more investigating judges would be added. However, at this writing, this had not yet been done.[41] In addition, the military court in Abidjan has completed one major trial for post-election crimes, in which five former Gbagbo military officials, including General Bruno Dogbo Blé, the former head of the Republican Guard, were convicted of abduction and murder. Dogbo Blé was sentenced to 15 years’ imprisonment.[42]

Staff in the Special Investigative Cell, Ministry of Justice officials, and some civil society activists cited the creation of the Special Investigative Cell as evidence that the government has some political will to pursue accountability.[43] Indeed, creating a specialized unit to handle the investigation and prosecution of serious international crimes can help prosecutors, investigating judges, and judicial police develop the expertise needed to handle these often-complex cases.[44] There has been movement towards accountability: more than 150 individuals have been charged with post-election crimes, including Simone Gbagbo, the wife of former President Laurent Gbagbo, and Charles Blé Goudé, Gbagbo’s youth minister during the crisis.[45]

To date, however, none of those charged with post-election crimes comes from the pro-Ouattara forces. [46] The absence of prosecutions against pro-Ouattara forces is especially significant in light of findings by the international commission of inquiry, the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, the United Nations Operation in Côte d’Ivoire, the International Federation of Human Rights, Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, an Ivorian coalition of human rights organizations known as the Group of Ivorian Actors for Human Rights (Regroupement des Acteurs Ivoriens des Droits de l’Homme), and President Ouattara’s own National Commission of Inquiry about likely war crimes and crimes against humanity committed by pro-Ouattara forces.[47] The skewed approach to accountability to date supports the widely held sentiment in Côte d’Ivoire that the government is only interested in pursuing the Gbagbo side.[48] The last two reports of the UN independent expert on the human rights situation in Côte d’Ivoire have similarly raised concerns about the absence of impartiality when it comes to justice for post-election crimes.[49]

The one-sided approach to accountability thus far in Côte d’Ivoire stands in stark contrast to the consistent promises of impartial justice made by President Ouattara’s government. [50]

Several civil society activists and two senior diplomats in Abidjan told Human Rights Watch that the one-sided approach to accountability is partially due to the precarious control President Ouattara still exerts over the military.[51] One senior diplomat expressed concern that the prosecution of even foot soldiers or low-level commanders from the FRCI could threaten security.[52] Several leaders of an Ivorian professional association also said that the spate of attacks on Ivorian military installations in August and September 2012 further dimmed the prospect for impartial accountability; some felt that the country needed to achieve a measure of stability before impartial accountability could be pursued.[53]

Côte d’Ivoire indeed faced legitimate threats to its national security in the second half of 2012. And the nature of some of the attacks, combined with additional credible evidence, gave weight to the Ivorian government’s theory that many of the attacks were waged by pro-Gbagbo militants.[54]

But, rather than cautioning authorities against pursuing impartial justice, the recent security threats show the urgent need for the Special Investigative Cell to make progress in its investigations into crimes on both sides. The failure to bring to account suspected perpetrators of grave crimes risks emboldening them and others to continue resorting to the same types of abuses during moments of tension. This is precisely what happened in response to the August security threats, after which members of the Republican Forces committed widespread human rights abuses against young men from pro-Gbagbo ethnic groups, including mass arbitrary arrests, illegal detention, extortion, cruel and inhuman treatment, and, in some cases, torture.[55]

In a November 2012 report, Human Rights Watch documented that many of the worst abuses were perpetrated by troops under the command of Ousmane Coulibaly, known by his nom de guerre “Bin Laden.” He was also implicated by Human Rights Watch during the post-election crisis as one of the FRCI leaders under whose command soldiers committed dozens of summary executions and frequent acts of torture during the final battle for Abidjan in April and May 2011.[56] Impunity makes it more likely that the same authors will commit the same crimes. Ongoing abuses by the Ivorian military, and in particular the targeting of people largely on the basis of their ethnicity and perceived political preference, risk further fueling the dangerous communal divisions at the root of the security threats.

Chronic impunity has fed repeated episodes of violence in Côte d’Ivoire for over a decade, underscoring that justice, in addition to giving victims the redress they deserve, is critical to achieving durable stability. As one civil society actor put it, “Justice has to proceed [impartially] if there is to be reconciliation. There was the same hatred, the same animosity, in the killing done by both sides. It will reduce tension if we recognize this and see justice on both sides.”[57]

The imperative of pursuing justice for serious international crimes does not diminish the difficulty in doing so. Holding to account even lower ranking suspects within the forces that helped arrest Gbagbo and consolidate the current government’s hold on power may prove to be deeply unpopular. In a divided society like Côte d’Ivoire, there may be opposition to impartial justice not only by possible targets but also segments of the population who still firmly believe that pro-Ouattara supporters were justified in committing crimes under the circumstances. Moves in the direction of pursuing impartial justice may very well spark outcries.

At the same time, without justice to end the culture of impunity, history risks repeating itself. Another civil society actor put it this way, “If we remain on the path we’re currently on, we will return to where we were before. There will be another crisis…. The impunity of today leads to the crimes of tomorrow.”[58] Indeed, the view that impartial justice is a vital ingredient for reconciliation was shared widely among those interviewed by Human Rights Watch for this report, as was the concern that its absence would fuel violence in the future.[59] cost of ignoring justice is simply too high. Moreover, steps to pursue those suspected of committing serious international crimes that are affiliated with the government in power can go a long way to inspire confidence in the rule of law.[60]

Dialogue, Truth, and Reconciliation Commission

Led by former Prime Minister Charles Konan Banny, the Dialogue, Truth, and Reconciliation Commission is composed of three vice presidents and seven commissioners representing constituencies across Côte d’Ivoire and the diaspora.[61] The CDVR’s stated objectives are to shed light on root causes of the post-election crisis, the acts and patterns of violations, and ways for the country to overcome these legacies through reconciliation and recognition of those who were victimized.[62] It can also make recommendations on institutional reforms with the aim of improving the protection of human rights.[63]

In its preparatory phase, CDVR members travelled around the country to open the process of reconciliation and to inform the public of the CDVR’s mission. This phase concluded with the period of mourning and purification.[64] The CDVR then met with community representatives and sought input from the wider population on how to give meaning to the decree creating the commission. According to a high-level CDVR official interviewed for this report, Ivorians repeatedly stressed that the CDVR should cover events beginning in 2002.[65] The official also expressed concern that the ongoing one-sided justice for post-election crimes could prejudice the implementation of the CDVR’s mandate.[66]

At the time of Human Rights Watch’s field work, the CDVR was still in the process of meeting with communities to discuss, in local languages, its mission and mandate.[67] The CDVR’s mandate was set to end in September 2013, by which point it was supposed to have taken and corroborated victim, witness, and perpetrator statements; written a report of its findings; and determined appropriate reparations, financial and symbolic.[68] In addition, the CDVR has proposed the creation of 36 sub-commissions across the country. At this writing, at least 23 of these commissions were set to be operational to continue with consultations with the local population.[69]

A comprehensive analysis of the CDVR’s work is beyond the scope of this report. CDVR officials expressed frustration to Human Rights Watch, saying their progress has been very slow, in part because of a lack of government funding.[70] However, the commission has received some government funding, in addition to external funding from, among others, the UN Peacebuilding Fund, the West African Economic and Monetary Union, and the African Development Bank.[71] The CDVR has also confronted resistance to its work by members of the pro-Gbagbo Ivorian Popular Front (Front Populaire Ivoirien, FPI).[72] In October 2012, President Ouattara and the CDVR President Banny met to reinvigorate the commission’s work.[73]

Further, at this writing the CDVR had not yet established a formal relationship with the Special Investigative Cell.[74] This is concerning since both institutions are mandated to investigate the same events, meaning they will often be seeking the same information, funding, and witnesses, including detainees who may already be in custody. Lessons from the experience of the simultaneous operation in Sierra Leone of a truth and reconciliation commission and a special court with criminal jurisdiction underscore the importance of establishing from the outset a clear relationship and modalities for addressing the conflicts that emerge between the two institutions.[75] There have been efforts to establish a platform to enable information sharing and coordination between all of the transitional justice institutions in Côte d’Ivoire, although it had not yet been concluded at this writing.[76] Human Rights Watch believes that the minister of justice, human rights, and public liberties should press for the conclusion of such an agreement as soon as possible.

International Steps towards Accountability

Given the repeated episodes of politico-military violence that have plagued Côte d’Ivoire for over a decade, it is unsurprising that the call for international justice for serious international crimes in Côte d’Ivoire has been longstanding. In April of 2003, then-President Gbagbo submitted a declaration under article 12(3) of the Rome Statute, submitting Côte d’Ivoire to the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court (ICC) for crimes falling under its jurisdiction since September 19, 2002.[77] The validity of the declaration was confirmed by President Ouattara in December 2010, when he asked the ICC to examine crimes committed since March 2004.[78] The request was reaffirmed in May 2011, although this time he asked the ICC to limit its investigation to crimes committed after November 28, 2010.[79]

In October 2011, the ICC judges authorized then-Prosecutor Luis Moreno-Ocampo to open an investigation under his propio motu power, initially for crimes committed after November 28, 2010. ICC judges have since expanded the scope of the investigation to include crimes committed after September 19, 2002, based on the Gbagbo government’s initial request in 2003.[80] Once opened, the investigation initially proceeded swiftly: in late November 2011, former President Gbagbo was arrested on an ICC arrest warrant alleging he was an indirect co-author for four counts of crimes against humanity during the post-election crisis.[81] On November 29, 2011, Ivorian authorities surrendered him to the ICC in The Hague, where he remains in custody pending a decision by ICC judges as to whether there is enough evidence to send his case to trial.[82] In late November 2012 the ICC unsealed an arrest warrant—originally issued in February 2012—against former President Gbagbo’s wife, Simone Gbagbo. She has also been charged with four counts of crimes against humanity allegedly committed during the same period.[83] At this writing, she remains in custody in Côte d’Ivoire where she is charged with genocide, among other crimes, for acts committed during the post-election crisis.[84] The government has indicated that it is “looking closely” at the ICC request for her arrest and surrender.[85] Human Rights Watch strongly urges the Ivorian government to comply with its obligation under the Rome Statute to cooperate with the ICC and surrender Simone Gbagbo to the court or, as an alternative, challenge the admissibility of her case before the ICC because it is trying her for the same events.

The Office of the Prosecutor (OTP), now under the leadership of Fatou Bensouda, has indicated that its investigations are ongoing and impartial.[86] Despite ample evidence of crimes committed by pro-Ouattara forces that could fall under the ICC’s jurisdiction, no one has yet been indicted.[87] The OTP’s lack of action against pro-Ouattara forces reflects its pursuit of a “sequential” approach, where the office conducts investigations against one group at a time—meaning it will conclude its investigations against the Gbagbo side before pursuing pro-Ouattara forces.[88]

Human Rights Watch appreciates the challenges facing the ICC which may make it difficult to pursue all groups at the same time, at least initially. The ICC’s broad jurisdiction means that the prosecutor can, and does, act in a number of unrelated country situations simultaneously, stretching its limited resources. Further, the office must rely to an extent on the government’s permission to access the country to investigate crime scenes and interview witnesses, among other tasks. Against this backdrop, the attraction of proceeding incrementally may seem impossible to resist, especially in the face of ready cooperation by the government to proceed against one side. Indeed, in Côte d’Ivoire, the Ouattara government was ready to help the ICC build a case quickly against Gbagbo, particularly amidst concerns that Gbagbo’s continued presence in the country posed an ongoing security threat. From a practical point of view, the Ivorian government’s incentive to cooperate with the ICC was considerable, as the government sought to achieve its primary goal: Gbagbo’s quick surrender to the ICC.

At the same time, Ivorian civil society activists told Human Rights Watch that the ICC’s quick action against Gbagbo effectively diminished its leverage when it comes to securing ongoing cooperation from Ivorian authorities, especially for ICC orders against forces loyal to the government.[89] Had the Office of the Prosecutor investigated allegations and issued arrest warrants against alleged perpetrators from both sides simultaneously, it would have been in a stronger position to see its orders executed. Adopting a simultaneous rather than a sequential approach was a feasible option, given that many victims of crimes committed by pro-Ouattara forces could have been easily found in refugee camps, internally displaced persons’ camps, and through traditional and neighborhood leaders in pro-Gbagbo areas.

As more time has passed without action against anyone from the Ouattara camp, the ICC has been increasingly viewed as “playing politics” in Côte d’Ivoire, feeding the perception that only one side has access to justice. [90] Ivorian civil society activists and others said the delay in investigations associated with the sequential approach has undermined the ICC’s credibility among the wider population. [91] In a country where the ICC’s legitimacy by example is most needed, the court’s independence and impartiality are now routinely questioned.

In addition to affecting its credibility among the Ivorian population, the ICC’s sequential approach has had an unfortunate spillover effect in Côte d’Ivoire. As one civil society actor interviewed by Human Rights Watch noted,

A lot of Ivorians are waiting for [the ICC] to charge someone from the Ouattara camp. If they stop at Gbagbo, there will be a problem. If they take a couple more from the Gbagbo camp [without anyone from the Ouattara camp], there will be a problem. The ICC needs to be an example of fairness and impartiality to our own justice system, but instead it has the same problems we do here. It’s showing the government here that slow progress [toward pro-Gbagbo trials] and being one-sided is acceptable.[92]

Indeed, Guillaume Soro, Ouattara’s former prime minister and the current head of Côte d’Ivoire’s National Assembly, made this very point when asked about the lack of justice for crimes committed by his side’s forces: “It was precisely in order not to be accused of victor’s justice that we brought in the International Criminal Court … [which] people cannot claim to be complaisant or to pick sides…. Up until now the ICC has been invited to come investigate in Côte d’Ivoire. Yet, the ICC, to my knowledge, has only issued four arrest warrants, [all against the Gbagbo side]. You will agree that the ICC has decided on the basis of its investigations.”[93]

The ICC has consistently emphasized the impartiality of its ongoing investigations in its public messaging around the Gbagbo cases.[94] While such statements are important, they are simply not enough to manage the fallout of pursuing a one-sided approach over the long term—consequences that extend far beyond those to the court’s reputation. The ICC should therefore continue its investigations against pro-Ouattara forces who may have committed crimes in the court’s jurisdiction with a view to, evidence permitting, bringing forth cases as soon as possible. Issuing warrants against members of the pro-Ouattara forces, in addition to reinforcing the ICC’s impartiality, could effectively open the space for prosecutorial and judicial authorities to do the same in Côte d’Ivoire. Additional recommendations for the ICC will be discussed in Section IV of this report.

III. Challenges to Realizing Accountability

The frequent resort to violence in Côte d’Ivoire to resolve disputes on issues ranging from politics to land conflict has laid bare the weakness of the rule of law in the country, further fueled by the lack of credible justice for the grave crimes committed during the decade of violence preceding the 2010 elections. Even before the 2010-2011 post-election crisis, the judicial system was plagued by insufficient material and financial resources, inefficient proceedings, the politicization of its personnel, inadequate case management systems, corruption, and poor public perception. The enormity of the task of re-establishing the rule of law swelled following the post-election crisis.[95]

In the country’s south, seventeen of the twenty six courts were partially damaged or looted during this period; courts effectively ceased to function. In the north, judges and prosecutors had only begun to return to their posts after more than seven years during which the Forces Nouvelles rebel group controlled that part of the country, including de facto policing and judicial functions. Many court officials in the north once again abandoned their posts after conflict resumed. Many prisons in the south were also damaged when armed groups from one side or the other broke them open to create chaos or to target new recruits. By conflict’s end, few prison facilities continued to function in the south; in the north, only three of the eleven prisons were operational prior to the crisis.[96]

Since taking office, President Ouattara’s government has taken steps to address these glaring deficiencies. The government has increased from 2 to 3 percent the amount of the national budget allocated to the justice sector over a five year period.[97] Similarly, donors have poured millions of dollars into the justice sector to support national rehabilitation efforts of the entire system. In April 2012 the Ministry of Justice finalized a national justice sector strategy, which forms the basis for interventions in the justice and prison sectors by the government, the United Nations, the European Union, and other partners from 2012 to 2015.[98] At this writing, the corresponding action plan, which identifies how the priorities will be implemented and will serve as a roadmap for international partners supporting justice reform, had yet to be finalized by the Ministry of Justice.[99]

As mentioned above in Section II, President Ouattara has specifically flagged in his rhetoric the need for independent and impartial justice to address the pervasive problem of impunity for grave crimes. The Special Investigative Cell, the National Commission of Inquiry, and the Dialogue, Truth, and Reconciliation Commission are indeed steps in that direction. But the lack of meaningful accountability against pro-Ouattara forces for atrocity crimes underscores the growing chasm between rhetoric and reality. More concrete action is needed to realize independent and impartial justice.

There are a number of areas where the Ouattara government and donors could provide practical assistance to see results when it comes to accountability for serious international crimes. As a general point, given the complexity of pursuing serious international crimes, all of those engaged in prosecuting, trying, and defending against allegations of serious international crimes would benefit from targeted, practical training to develop their capacity. These trainings should address real needs as identified by the practitioners working on these cases. For instance, prosecutors could be trained in how to use existing modes of liability under Ivorian law to target senior officials who ordered or failed to adequately respond to the commission of serious international crimes.[100] Workshops on the elements of crimes and modes of liability in the Rome Statute and relevant defenses—for prosecutors, judges, and defense lawyers—as compared to domestic law could also be beneficial.

Other areas where the government— with donor assistance as needed— could provide material and technical support to help judicial and prosecutorial authorities strengthen their ability to pursue serious international crime cases include: strengthening judicial and prosecutorial independence, strengthening prosecutions by signaling for prosecutors the need to put in place a more effective and transparent prosecutorial strategy, improving investigative capacity by providing material and technical support as needed, solidifying the legal basis of the Special Investigative Cell, improving the fair trial rights of defendants, establishing an effective system for witness protection, and bolstering security for judges, prosecutors, and defense lawyers. Each of these areas will be discussed in more detail below.

Strengthening Judicial and Prosecutorial Independence

Judicial independence, meaning the real and perceived ability to act without political influence, is the cornerstone of democracy, good governance, and rule of law. Judges must also be able to withstand temptation to circumvent the law for personal gain, both in appearance and reality. It is only when judges and prosecutors can and appear to operate free from influence or corruption that they are able to adjudicate cases impartially—key preconditions to inspire public confidence in the administration of justice. Independence and impartiality are critical when it comes to trying serious international crime cases, which are especially sensitive because they are often committed along ethnic or political lines and their masterminds may continue to occupy positions of power.

At the same time, these core principles are weakest in countries emerging from conflict or violence resulting from the complete breakdown of the rule of law, like in Côte d’Ivoire. Indeed, senior Ministry of Justice officials interviewed by Human Rights Watch pointed to two pivotal judicial decisions as symbols of the politicization of the judiciary: first, in 2000, when the Supreme Court declared Alassane Ouattara, among others, ineligible to stand in the presidential elections; and second, in 2010, when the Constitutional Court nullified the results of the Independent Electoral Commission and declared President Gbagbo the winner of the election.[101] Civil society activists and government officials said that both decisions reflected the lack of independence of the judicial system and helped trigger the onslaught of politico-military violence that resulted in the commission of mass atrocities.