Abbreviations

|

AFJ-CI |

Association des Femmes Juristes de Côte d’Ivoire (Association of Women Jurists for Côte d’Ivoire) |

|

CDVR |

Commission Dialogue, Vérité et Réconciliation (Commission on Dialogue, Truth and Reconciliation) |

|

CGFR |

Comité de Gestion Foncière Rurale (Committee for Rural Land Management) |

|

CNE |

Commission Nationale d’Enquête (National Commission of Inquiry) |

|

CONARIV |

Commission Nationale pour la Réconciliation et l’Indemnisation des Victims (National Commission for Reconciliation and Indemnification of Victims) |

|

CSEI |

La Cellule Spéciale d’Enquête et d’Instruction (Special Investigative and Examination Cell) |

|

CSM |

Conseil Supérieur de la Magistrature (High Judicial Council) |

|

CVGFR |

Comité Villageois de Gestion Foncière Rurale (Village Committee for Rural Land Management) |

|

DAP |

Direction de l'Administration Pénitentiaire (Direction of Prison Administration) |

|

DDR |

Disarmament, demobilization and reintegration |

|

DST |

La Direction de la Surveillance du Territoire (National Surveillance Directorate) |

|

FN |

Forces Nouvelles (New Forces) |

|

FRCI |

Forces Républicaines de Côte d’Ivoire (Republican Forces of Côte d’Ivoire) |

|

ICC |

International Criminal Court |

|

OGE-CI |

L’Ordre des Géomètres Experts de Côte d’Ivoire (Order of Expert Land Surveyors) |

|

OHCHR |

United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights |

|

ONUCI |

Opération des Nations Unies en Côte d'Ivoire (United Nations Operation in Côte d’Ivoire) |

|

PNCS |

Programme National de Cohésion Sociale (National Program for Social Cohesion) |

|

RDR |

Rassemblement des Républicains (Rally of the Republicans, President Ouattara’s political party) |

|

RTI |

Radiodiffusion Télévision Ivoirienne (Ivorian Radio and Television) |

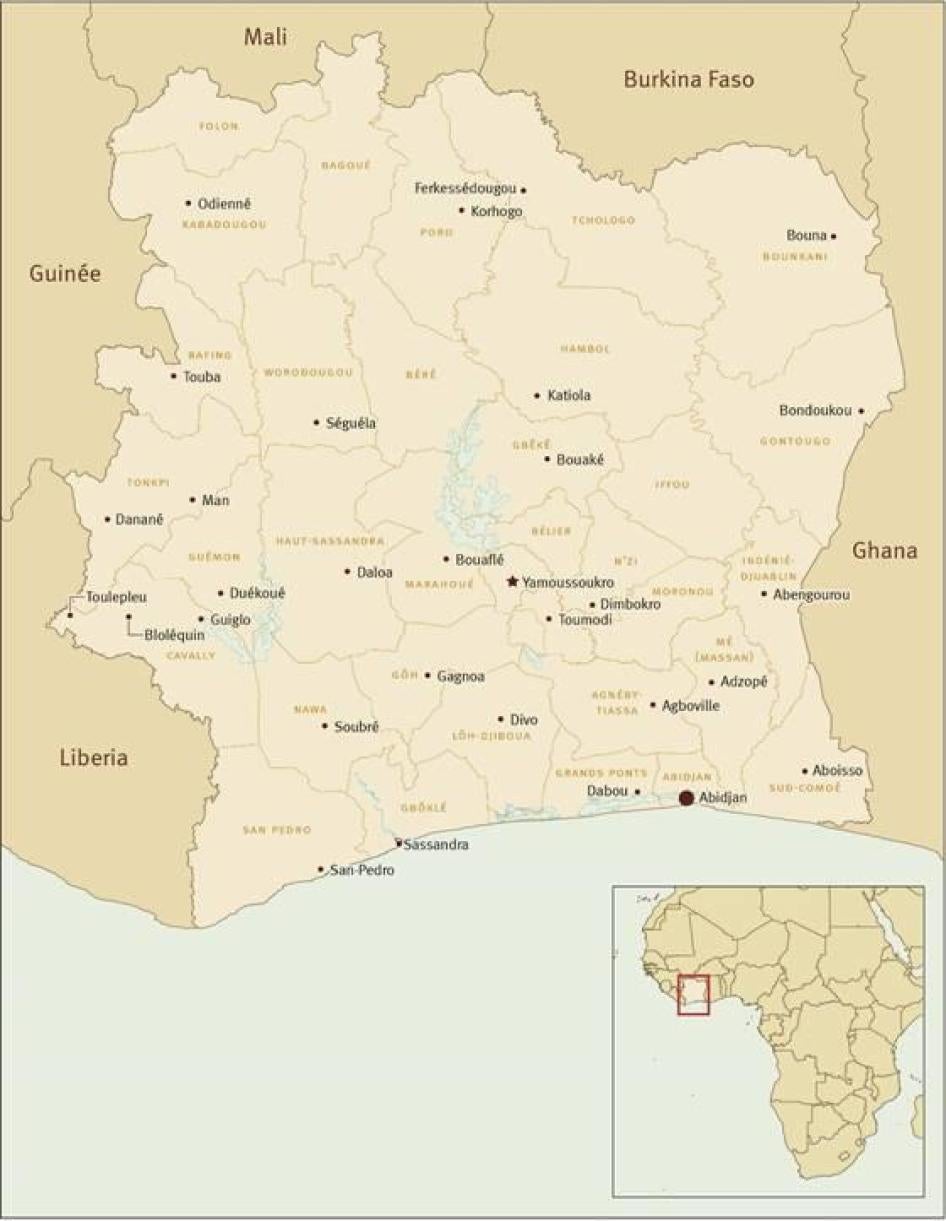

Map of Côte d’Ivoire

Summary

On October 25, 2015, the Ivorian people elected President Alassane Ouattara to a second term, in an election deemed free and fair by the African Union (AU) and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). The election was largely devoid of the violence that had accompanied previous polls in 2000 and 2010.

Côte d’Ivoire is still less than five years removed from a decade of conflict and unrest, rooted in both political discord and ethno-communal tensions, which culminated in the 2010-2011 post-election crisis. The refusal of then-president Laurent Gbagbo to accept Ouattara as the winner of the 2010 election led to an armed conflict during which at least 3,000 civilians were killed and more than 150 women were raped, with serious human rights violations committed by both sides.

In advance of the October election, President Ouattara campaigned on a promise to consolidate peace and security and to do more to ensure ordinary Ivorians benefit from economic growth. To distance Côte d’Ivoire from the conflict and instability that have characterized the country for so many years, President Ouattara’s government should use his second term to ensure much needed progress on strengthening the rule of law and addressing the deep-rooted problems that gave rise to violence in the first place.

During three research missions in October 2014 and May and July 2015, Human Rights Watch assessed the government’s progress in addressing the legacies of the country’s violent past and asked Ivorians about the key human rights priorities for the next five years. Human Rights Watch interviewed more than 200 victims of human rights violations, local government officials and traditional leaders, Ivorian lawyers and judges, members of the security forces, national and international civil society organizations, human rights defenders, humanitarian organizations, journalists, government officials in key ministries, diplomats, and officials from the United Nations (UN) and international financial institutions.

Ouattara’s First Term in Office

Interviewees told Human Rights Watch that much of President Ouattara’s first term was devoted to dealing with the immediate consequences of the 2010-2011 post-election crisis. They cited as progress improved security country-wide, fewer abuses by security forces, increased support for investigations into past atrocities, the reopening of courts and prisons across Côte d’Ivoire, and the successful mediation of land conflicts by traditional leaders and local government officials.

Human Rights Watch found, however, that while there has been progress in certain key areas, in many cases the positive steps taken during President Ouattara’s first term only marked the beginning of a long road to meaningful reform. In others, the government failed to properly address more deep-rooted issues. President Ouattara’s government needs to do more to ensure impartial accountability for past human rights abuses, confront persistent weaknesses within the justice system, complete the security sector reform process, provide reparative justice to victims, and address land dispossession in western Côte d’Ivoire.

Accountability for Past Human Rights Abuses

During the decade of conflict and unrest that culminated in the 2010-2011 post-election crisis, serious human rights abuses were committed by all parties, including Gbagbo-era security forces and the Forces Nouvelles (“New Forces”) rebels who eventually helped bring Ouattara to power. The culture of impunity that allowed perpetrators to escape justice for atrocities was a key factor in perpetuating abuses.

No one responsible for the human rights violations committed during election-related violence in 2000 or an armed conflict in 2002-2003 was convicted for their alleged crimes. Similarly, five years after the 2010-2011 post-election crisis, the vast majority of the commanders and leaders implicated in serious human rights violations—on both sides of the military-political divide—have not been properly held to account for those abuses.

President Ouattara has said that he is committed to ensuring the prosecution of those who perpetrated atrocities during the post-election crisis, and that all future trials will occur in national courts. However, although Ivorian judges have recently made progress in investigations, it remains unclear whether Ouattara’s government sufficiently supports the judiciary in bringing perpetrators to justice, particularly commanders from pro-Ouattara forces.

In 2011, the government created the Special Investigative Cell (since renamed the Special Investigative and Examination Cell, Cellule Spéciale d'Enquête et d'Instruction, CSEI), a taskforce of judges and prosecutors to investigate crimes committed during the post-election crisis. After years of inadequate government support, the CSEI received increased resources in late 2014 and in 2015 charged more than 20 perpetrators—including high-level commanders from both sides of the conflict—for their role in human rights abuses during the post-election crisis. The government’s support for the CSEI, however, is fragile. In mid-2015, the CSEI faced pressure from the executive to finish key investigations prematurely.

At the international level, in early 2016 the International Criminal Court (ICC) is due to begin the trial of former president Laurent Gbagbo and Charles Blé Goudé, a former youth minister and leader of a pro-Gbagbo militia group. The ICC has also charged Gbagbo’s wife, Simone, with crimes against humanity committed during the post-election crisis, but Côte d’Ivoire has refused to transfer her to The Hague to face trial.

Until now, however, the ICC has yet to bring charges against anyone for abuses committed by pro-Ouattara forces during the post-election crisis. The one-sided focus of the ICC’s cases has polarized opinion about the court and undermined perceptions of its legitimacy, particularly among Gbagbo supporters. The ICC Prosecutor’s office has only recently intensified its on-the-ground investigations into pro-Ouattara forces. Although President Ouattara has said that no further suspects will be transferred to the ICC, these investigations remain a vital lever to push for impartial justice at a national level.

During his second term in office, President Ouattara should provide adequate support to the CSEI and avoid political interference in human rights cases, particularly those involving commanders who fought on his side of the post-election crisis. His government should also cooperate with the ICC’s investigations and transfer suspects the ICC seeks to try. In addition, Ouattara should state publicly and unequivocally that he will not grant pardons to anyone convicted of human rights crimes.

Rebuilding the Justice System and Improving Prison Conditions

President Ouattara has made progress in rebuilding a justice system devastated by Côte d’Ivoire’s successive crises, and he has successfully redeployed judicial personnel to areas in the north that were, prior to the 2010-2011 post-election crisis, outside government control.

However, not enough has been done to address the underlying and less visible problems that have plagued Côte d’Ivoire’s courts since before the post-election crisis. While the government’s failure to implement some of the reforms scheduled to be completed during Ouattara’s first term—such as the adoption of laws to strengthen the independence of the judiciary—was reflective of a lack of political will, other reforms were hamstrung by the limited budget allocated to the courts and judiciary. In 2014, the justice sector budget was just 1.4 percent of the overall national budget.

As President Ouattara’s government begins its second term, several priority areas deserve urgent attention if the justice system is to adequately protect the rights of Ivorians, including the lack of independence of the judiciary, corruption, excessive prolonged pretrial detention, poor prison conditions, and lack of access to legal representation.

President Ouattara’s government has made little progress in ensuring that the judiciary is independent of the executive arm of government. The Ministry of Justice has not finalized laws initially drafted in 2012 that would strengthen the independence of the High Judicial Council (Conseil Supérieur de la Magistrature, CSM), the body responsible for the appointment and discipline of magistrates, and protect against political interference in the promotion and evaluation of judges.

Furthermore, the government has done too little to address corruption in the justice sector. Despite Ouattara’s 2011 promise that corrupt judges would be fired, Ivorian jurists told Human Rights Watch that they were not aware of any judges being disciplined or prosecuted for corruption since 2012.

Ivorian courts also continue to place far too many people in pretrial detention, with approximately 40 percent of people in Ivorian jails in pretrial detention. The prevalence of pretrial detention and the slow pace of case resolution exacerbate over-crowding, with almost half of the country’s prisons severely overpopulated. Once in detention, many detainees, particularly those accused of serious offenses, wait years before being tried or released. The Ivorian government has also failed to adequately address chronic problems within the corrections sector, including lack of adequate nutrition, poor sanitation, and insufficient access to medical care.

President Ouattara’s government has also done little to address Côte d’Ivoire’s ailing legal aid system. Many defendants in criminal cases only receive legal representation at the trial phase; others do not receive it at all. Indigent litigants in both civil and criminal cases have the right to request free legal assistance, but very few know the procedure for doing so – the National Legal Aid Bureau receives only a few hundred requests each year. Much of the burden for providing litigants with legal advice and representation therefore falls on nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), particularly legal clinics supported by international donors.

President Ouattara should make building a justice system that respects and protects rights a priority for his second term, including by ensuring the justice sector has sufficient resources. In light of President Ouattara’s promise to revise Côte d’Ivoire’s constitution, the government should use the constitutional reform process to bolster the independence of the CSM and protect judges from executive interference. The government should also urgently review the National Action Plan for the Justice Sector, a roadmap for reform adopted by the Council of Ministers in June 2013, to create a revised plan for 2016-2020, including new target dates for the completion of key reforms not yet implemented.

Reforming the Security Sector

Security sector reform was a priority in President Ouattara’s first term, and the conduct of the security forces, including the military, has improved since the 2010-2011 post-election crisis. The government has also made progress in transferring law enforcement responsibilities from the armed forces to police and gendarmes, although they often lack sufficient equipment and training to protect citizens from criminality.

Despite the progress made, however, ongoing violations by security forces and the lack of accountability for them continued during President Ouattara’s first term in office. In 2012, the mass arrests, illegal detention and torture committed by the army in response to attacks on military installations by Gbagbo sympathizers demonstrated the challenge Ouattara faced in addressing the security forces’ human rights record.

Although the army’s conduct has since improved, as recently as 2014 soldiers responded to attacks on military outposts by holding suspects in unauthorized detention facilities and torturing multiple detainees. Multiple sources also expressed concerns about illegal detentions by the National Surveillance Directorate (La Direction de la Surveillance du Territoire, DST), a national security-focused intelligence service under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of the Interior. In the lead up to the 2015 presidential election, the DST detained several opposition activists in unauthorized locations and without access to legal assistance.

Furthermore, although overall the conduct of the security forces has improved, soldiers, police, and gendarmes continue to extort money while manning illegal checkpoints, particularly in rural areas. Several Ivorian army commanders are also enriching themselves through extortion, smuggling, and parallel tax systems that they impose on the export of natural resources, mirroring the military-economic network that the Forces Nouvelles rebels operated when northern Côte d’Ivoire was under their control.

The failure to investigate and prosecute these commanders is indicative of wider impunity within the security forces. Even when soldiers commit serious crimes outside the course of their duties, such as sexual violence, they are rarely prosecuted in civilian courts. The military justice system, which currently has jurisdiction over police, gendarmes and soldiers, is under-resourced, with only one military tribunal for the whole country. The system is in need of comprehensive reform to strengthen its independence and to limit its jurisdiction to military offenses committed by military personnel.

During his second term, President Ouattara should complete the security sector reforms necessary to professionalize the armed forces and prevent future abuses, such as the promulgation of a new law on the organization of the national defense and armed forces, and the creation of a more effective, rights-respecting military justice system. The role played by former Forces Nouvelles commanders in ongoing abuses also underscores the importance of holding them accountable for the human rights violations they committed during the 2010-2011 post-election crisis.

Truth-Telling and Reparations

In the aftermath of the 2010-2011 post-election crisis, Côte d’Ivoire established a Commission on Dialogue, Truth, and Reconciliation (Commission Dialogue, Vérité, et Réconciliation, CDVR) to promote reconciliation, uncover the truth about past human rights violations, and provide recommendations on how to prevent future abuses and provide reparations to victims.

The CDVR, whose mandate ended in September 2014, took testimony from more than 72,000 Ivorians, including over 28,000 women. In December 2014, the commission’s president, former Prime Minister Charles Konan Banny, presented the CDVR’s final report to President Ouattara.

The CDVR’s report, however, has not been made public, and the presidency has never provided an explanation for the delay in doing so. The only concrete action President Ouattara took upon receiving the CDVR report was to commit to making 10 billion FCFA (approximately US $16.2 million) available for the indemnification of victims, an important step but not a substitute for a fuller discussion of the report’s recommendations.

In March 2015, the government created a successor to the CDVR, the National Commission for Reconciliation and Indemnification of Victims (Commission Nationale pour la Réconciliation et l’Indemnisation des Victims, CONARIV), to oversee a reparations program for victims of abuses committed from 1990 to 2012. Another government agency, the National Program for Social Cohesion (Programme National de Cohésion Sociale, PNCS), is to execute the reparations program.

CONARIV is working to compile an initial list of victims and determine who will be eligible for reparations and what they will receive. An initial round of reparations, however, which began in August 2015 before CONARIV had even finalized guidelines for reparations, raised expectations among victims as to when they will receive reparations and how much they will get. This first round of reparations will cost 6-8 billion FCFA (US $10-13 million) of the 10 billion FCFA Ouattara said would initially be available, leading to concerns that the government will ultimately struggle to meet victims’ expectations.

To trigger dialogue on how to further national reconciliation and prevent future abuses, President Ouattara should publish the CDVR report, and the National Assembly should debate it in a special committee and in a plenary session. The government should also publish an official response to the CDVR report, including details on which recommendations it endorses and how it is implementing them.

To manage victims’ expectations over reparations, CONARIV and the PNCS should expedite consultations on, and the adoption of, a law defining who is eligible for reparations and what they will receive. CONARIV should also increase its outreach to and communication with victims’ associations.

Addressing Land Dispossession in the West

Deep inter-communal tensions linked to land dispossession are one reason why western Côte d’Ivoire has played host to many of the worst atrocities committed in the country.

The 2010-2011 crisis triggered a new wave of land dispossession, as landowners from pro-Gbagbo ethnic groups, who had fled in fear of reprisals from advancing pro-Ouattara forces, returned to find that their land had been illegally sold or occupied.

Although land conflicts in western Côte d’Ivoire have since become less prevalent, land dispossession remains a key driver of inter-communal tensions and local-level violence between western ethnic groups, immigrants from neighboring countries, and communities from other regions of Côte d’Ivoire.

The government’s land policy during President Ouattara’s first term focused on the implementation of a 1998 rural land law that sought to provide landowners with more security by converting customary claims to land certificates and eventually legal title. However, as of May 31, 2015, only 978 land certificates had been issued nationwide, and community leaders told Human Rights Watch that the process for obtaining them was too expensive and too complicated, making certificates inaccessible to ordinary Ivorians. The government has also made little progress in mapping village boundaries, so as to prevent fraudulent sales that exploit uncertain borders between villages.

Much of the burden for resolving land disputes currently falls on village chiefs and local administration officials, who have played a key role in mediating land dispossession cases related to the 2010-2011 post-election crisis.

However, the settlements reached before customary authorities are increasingly difficult to enforce, often discriminate against women, and frequently allow even those who occupied land in bad faith to remain on the land. Those implicated in illegal or fraudulent sales are rarely prosecuted.

As President Ouattara begins his second term, his government’s land policy faces two related challenges: the lack of implementation of the 1998 law and the continued reliance on customary dispute resolution mechanisms; and the recognition that customary authorities may find it increasingly difficult to find durable, rights-respecting solutions to land disputes.

In July 2015, the Ivorian government circulated a draft land policy that aims to facilitate implementation of the 1998 law by streamlining the steps necessary to obtain a land certificate and reducing the cost of doing so. The government has said that Ivorian NGOs and community leaders will have an opportunity to comment on the draft land policy in spring 2016, and it should ensure that men and women from all political and ethnic groups are able to fully participate in the consultation process.

As a key part of these consultations, the government should assess how to ensure that land disputes that arise during the implementation of the 1998 law are resolved fairly and in a timely manner. This may involve modifying or better supporting the village and sub-prefectural land committees that currently resolve disputes during the land certification process, or may require a new mechanism. The government should also ensure that anyone whose property rights have been violated by the decision of a customary or local government authority, including the village and sub-prefectural land committees created pursuant to the 1998 law, can appeal to the court system.

The Challenge for Ouattara’s Second Term

Although President Ouattara has only just begun his second term, many Ivorians are already looking towards the 2020 presidential election and fear the political fight to succeed him could once again lead to violence and instability. Côte d’Ivoire’s history shows that politicians are often willing to exploit ethnic tensions, weak judicial institutions, and ill-disciplined security forces in the battle for power.

President Ouattara must use his second term to combine economic growth and an effort to protect and fulfill economic and social rights with an equal commitment to fighting impunity, strengthening the rule of law, completing security sector reforms, and addressing the land conflicts at the root of many inter-ethnic tensions. If the new government fails to do so, the political uncertainty that could be triggered by President Ouattara’s departure will once again threaten the advances in rule of law and security on which Côte d’Ivoire’s economic recovery has been built.

Recommendations

To President Ouattara and the Government of Côte d’Ivoire

To Address Accountability for Past Abuses

- Support efforts by the Ivorian judiciary to prosecute in accordance with international fair trial standards all those responsible for killings, rapes, and other serious human rights violations, including those committed during the 2010-2011 post-election crisis, regardless of position, rank, or political affiliation.

- Ensure that the investigating judges and other judicial personnel tasked with investigating and adjudicating the human rights violations committed during the 2010-2011 post-election crisis are adequately resourced, protected, and supported by the Ministry of Justice.

- Cooperate with the ICC’s ongoing investigations and cases in Côte d’Ivoire in compliance with the government’s obligations under the Rome Statute, including by surrendering Simone Gbagbo to the ICC.

To Strengthen the Judiciary and Improve Prison Conditions

- Review the National Action Plan for the Justice Sector to create a revised plan for the period 2016-2020, including new target dates for the completion of key reforms not yet implemented. Prioritize actions to improve the independence and impartiality of the judiciary and tackle corruption.

- As part of a constitutional reform process, eliminate the president’s role as the head of the CSM and establish a process for appointing members of the CSM that is independent of executive influence.

- Finalize and submit to the National Assembly the codes and laws essential to rule of law reform that were drafted during President Ouattara’s first term, including the criminal procedure code and laws on the profession of magistrates, the prison system, and legal assistance.

- Empower the Inspector General of Judicial and Penitentiary Services to refer magistrates suspected of corruption directly to the CSM and prosecutor’s disciplinary commission, without the permission of the Minister of Justice. Make public the Inspector General’s reports and any disciplinary or criminal sanctions imposed against judges and prosecutors.

- Take concrete measures to address the extensive imposition of pretrial detention, including by providing the judiciary with the resources necessary to hold sessions of the Cour d’Assises at least every three months.

- Ensure all accused in criminal cases have access to adequate legal representation, regardless of their means.

- Finalize and adopt the Plan to Improve Prisons Conditions to address prisoners’ nutrition, sanitation, medical care, and access to educational opportunities and ensure sufficient resources are available for its implementation.

To Address Indiscipline and Impunity within the Security Forces

- Introduce a zero-tolerance policy on criminal behavior and human rights abuses by the army, police, and gendarmes.

- Investigate and prosecute, in accordance with international standards, members of the security forces against whom there is evidence of criminal responsibility for abuses.

- Increase the resources of the anti-racket unit to enable it to operate nationwide, and instruct the unit to focus on investigating commanders who are implicated in or facilitate extortion and racketeering.

- Adequately support and resource the military tribunal so that it becomes a functional institution, and limit its scope to the trial of military personnel implicated in military crimes. Ensure that officers of the court, including prosecutors and defense counsel, are fully independent of the military chain of command and governmental interference.

- Complete the return of primary authority over internal security to the police and gendarmerie, including through providing sufficient training and material support so that these forces can effectively undertake security functions.

- Cease immediately the holding and interrogating of civilians at military camps or unauthorized detention locations.

- Ensure that any civilian arrested is promptly brought to a police or gendarme station and that, in accordance with Ivorian and international law, any person arrested appears before a judge within 48 hours to consider the legality of detention and the charges against him or her.

To Respect Victims’ Rights to Truth and Reparations

- Publish the final report and recommendations of the CDVR and encourage the National Assembly to debate its contents and recommendations.

- Ensure that the conclusions of the CDVR report are accessible to Ivorians, including through the dissemination of a synopsis of the report’s findings.

- Draft and publish a white paper as an official response to the CDVR report, including details on which recommendations the government endorses and how it is implementing them.

- Expedite consultations on, and the adoption of, a law defining who is eligible for reparations and what they will receive. Instruct the leaders of CONARIV and the PNCS to negotiate terms of reference governing their relationship, with President Ouattara personally intervening to mediate areas of disagreement.

- In partnership with victims’ associations, assist CONARIV and the PNCS to conduct increased outreach to victims of human rights violations, including outside of Abidjan, to ensure victims are informed about the reparations process.

To Address Land Dispossession in Western Côte d’Ivoire

- Ensure that men and women from all political and ethnic groups are able to fully participate in consultations concerning the government’s draft land policy.

- As part of consultations over the draft land policy, assess how to ensure that land disputes related to the implementation of the 1998 rural land law are resolved fairly and in a timely manner. This may involve modifying or better supporting the village and sub-prefectural land committees created pursuant to the 1998 law or may require a new mechanism.

- Ensure, in accordance with the Ivorian constitution and international human rights law, that there is no discrimination against women, in law or in practice, in regards to the ability to formalize land ownership rights under the 1998 rural land law.

- Instruct sub-prefects, police, judicial police, and prosecutors to work together to investigate and prosecute fraudulent land sales. Penalties should ensure, at a minimum, that the bad-faith seller does not retain a profit from his fraud.

- Ensure that anyone whose property rights have been violated by the decision of a customary or local government authority, including the village and sub-prefectural land committees created pursuant to the 1998 law, can appeal to the court system.

- Accelerate the demarcation of village boundaries. Prioritize areas where land and inter-communal conflict are closely linked, including in western Côte d’Ivoire.

To the National Assembly

- Pass codes and laws essential to rule of law reform, including the criminal procedure code and laws on the profession of magistrates, the prison system, and legal assistance.

- Create a special multi-party committee, in accordance with the National Assembly bylaws, responsible for examining the report of the CDVR. Request the committee to report back to the full National Assembly and schedule time for debate in plenary sessions of the CDVR’s report.

- Conduct a public hearing into the activities of the DST, with a view to making recommendations on how to improve the DST’s human rights record.

- Ratify the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, and implement the Protocol through establishing an independent national body to carry out regular and ad hoc unannounced visits to all places of detention.

To France, the European Union, the United States, International Financial Institutions and Other International Partners

- Continue to prioritize the fight against impunity for past human rights abuses in political dialogue with the Ivorian authorities, reinforcing the importance of cooperation with the ICC and consistent government support for independent and impartial national justice.

- Support training and technical assistance for the staff of the CSEI.

- Monitor and speak out publicly more often against abuses by security forces, including detentions in unauthorized locations and without judicial oversight.

- Support the government’s formulation of a revised National Action Plan for the Justice Sector for the period 2016-2020, and advocate for the inclusion of reforms to improve the independence and impartiality of the judiciary and tackle corruption. Consider linking future funding for infrastructure improvement, with the exception of prison rehabilitation, to demonstrated progress in these areas.

- Continue to provide financial and technical assistance to the government’s security sector reform process, and include support for the reform of the military justice system.

- Provide financial and technical assistance to CONARIV and the PNCS on the design and implementation of reparations programs, including improved outreach to victims.

- Support consultations on the Ivorian government’s draft land policy to ensure that men and women from all political and ethnic groups are able to fully participate in the consultation process. Continue to support the demarcation of village boundaries.

To the United Nations Operation in Côte d’Ivoire

- Continue with private and public diplomacy pressing the government to maintain its support for fair and impartial justice for past human rights abuses.

- Monitor and speak out publicly more often against abuses by security forces, including detentions in unauthorized locations and without judicial oversight.

- Continue to provide financial and technical assistance to the government’s security sector reform process, and include support for reform of the military justice system.

- Provide financial and technical assistance to CONARIV and the PNCS on the design and implementation of reparations programs, including improved outreach to victims.

- In light of ONUCI’s impending drawdown, solicit the support of the Ivorian government and international donors for the maintenance of a United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) mission in Côte d’Ivoire.

To the United Nations Independent Expert on Capacity-Building and Technical Cooperation with Côte d’Ivoire in the Field of Human Rights

- Carefully monitor and speak out forcefully against human rights violations, and include dedicated sections in upcoming research and reports on abuses by the military in response to threats to state security, unlawful detention and mistreatment of detainees by the DST, and executive interference and corruption within the judiciary.

To the International Criminal Court, Office of the Prosecutor

- Continue with investigations against all sides of the 2010-2011 post-election crisis.

- Strengthen working-level relationships with Ivorian judges and prosecutors, particularly in the CSEI, in order to facilitate the sharing of information relating to investigations and identify opportunities for training the staff of the CSEI.

Methodology

Based primarily on information gathered during three research missions conducted in Côte d’Ivoire by Human Rights Watch between October 2014 and August 2015, this report assessed the government’s progress in addressing the legacies of the country’s violent past and asked Ivorians about the key human rights priorities for the next five years.

Human Rights Watch visited northern Côte d’Ivoire (Bouaké and surrounding areas) and towns in the west of the country (Bloléquin, Duékoué, Daloa, and Guiglo), as well as nearby villages. This research was supplemented with interviews conducted in Abidjan during each research mission and numerous telephone interviews undertaken between October 2014 and November 2015. In total, Human Rights Watch interviewed more than 200 people during the research for this report. The majority of interviews were conducted individually, although some group interviews were organized where participants preferred to be interviewed in groups and where there was no identifiable risk that this would put interviewees in danger of reprisals from any party. Human Rights Watch did not offer interviewees any incentive for speaking.

When traveling outside of Abidjan, Human Rights Watch interviewed customary and traditional leaders from diverse ethnic and immigrant groups; soldiers, police officers and gendarmes; local government officials; local civil society groups; humanitarian workers; and traders, bus owners, drivers and passengers, among others.

In Abidjan, Human Rights Watch interviewed Ivorian government officials in the Presidency, Prime Minister’s office, Ministry of Justice, Ministry of the Interior, and Ministry of Agriculture; Ivorian prosecutors, judges and lawyers; and senior military and law enforcement officials. Human Rights Watch also interviewed representatives from victims’ groups; international and national civil society groups; humanitarian organizations; diplomats; officials from the United Nations, international financial institutions, and the International Criminal Court; and journalists.

Many of the individuals interviewed wanted to speak candidly, but wished to retain their anonymity given the sensitivity of the issues they discussed. Many international and Ivorian officials were concerned that being identified in this report would expose them to sanctions from their superiors. As a result, we have used generic descriptions of interviewees throughout the report to respect the confidentiality of these sources.

I. Accountability for Past Abuses

Justice reestablishes balance. It was two people who fought, not just one side. Does the fact that you won give you the right to kill people? How can reconciliation happen if justice is not impartial? That justice can’t bring peace.

–Ivorian civil society activist[1]

Dismantling the architecture of impunity that underscored Côte d’Ivoire’s violent recent history needs to be at the top of the agenda for President Ouattara’s second term.

During the decade of conflict and instability that culminated in the 2010-2011 post-election crisis, Ivorians suffered unspeakably brutal crimes, including peaceful protestors gunned down, villagers dragged from their homes and executed in cold blood, detainees brutally tortured, men set alight in front of their families, and girls who were gang raped.[2]

And yet the vast majority of the commanders and leaders implicated in these abuses—on both sides of the military-political divide—have not been properly held to account.

Victims from all sides expressed frustration with the lack of accountability. An Ouattara supporter in Abobo who was a victim of sexual violence during the post-election crisis told Human Rights Watch, “The people responsible for abuses must be punished. We have suffered too much.”[3] A civilian from Yopougon who voted for Gbagbo in 2010 said, “We speak about justice, but where is the justice?”[4]

Opposition supporters are skeptical that Côte d’Ivoire’s courts will ever hold high-level perpetrators from pro-Ouattara forces accountable for the abuses that they committed during the 2010-2011 post-election crisis, with one saying, “It’s the party who wins that writes its history.”[5] Several opposition supporters told Human Rights Watch that the absence of impartial justice was a key reason for their continued hostility towards President Ouattara’s government, with one noting, “If reconciliation has not succeeded, it’s because of the lack of justice.”[6]

International human rights law requires that states investigate human rights violations effectively, promptly, thoroughly, and impartially and, where appropriate, take action against those allegedly responsible.[7] International criminal law requires such criminal investigations and prosecutions to be carried out for the most serious crimes, including war crimes, crimes against humanity, and torture.[8] Several victims told Human Rights Watch that it was important to pursue accountability against all sides to prevent future abuses and further reconciliation, with one saying: “We must sort out this question of impartial justice so that the post-election crisis doesn’t repeat itself.”[9]

A History of Impunity

On December 24, 1999, soldiers disgruntled over low pay seized power from Côte d’Ivoire’s then-president, Henri Konan Bédié, and asked General Robert Guei, the president’s chief of staff, to lead the government. Although Guei’s government organized presidential elections in 2000, a controversial constitutional amendment prevented Ouattara from contesting the election.[10] Later that year, following an October presidential election won by Laurent Gbagbo and December parliamentary elections, bloody clashes between security forces, Gbagbo sympathizers, and Ouattara supporters killed more than 200 people and injured hundreds.[11]

In September 2002, an attempted coup d’état against Gbagbo’s government by northern rebel groups triggered an armed conflict in which both the Forces Nouvelles[12] rebels and Gbagbo-aligned forces committed serious human rights crimes, including summary executions, indiscriminate attacks against civilians, sexual violence, and torture.

No one responsible for human rights violations committed during the 2000 election-related violence or the 2002-2003 armed conflict has been convicted for their alleged crimes.[13] A UN commission of inquiry report into human rights abuses committed during the 2002-2003 conflict, which included a confidential annex that reportedly listed 95 individuals deemed most responsible and deserving of criminal investigation, has never been made public by the UN.[14]

Many of those who escaped prosecution for abuses again played prominent roles in the 2010-2011 post-election crisis, when Gbagbo’s refusal to accept Ouattara as the winner of the 2010 poll triggered violence and a resumption of armed conflict, during which at least 3,000 civilians were killed and more than 150 women raped.

Avenues to Justice

Côte d’Ivoire is an example of the potential for close cooperation between national and international justice in the effort to fight impunity for human rights abuses, with International Criminal Court (ICC) proceedings operating in parallel to cases in Ivorian courts.

At a national level, serious human rights abuses committed during the 2010-2011 post-election crisis fall within the remit of the Cour d’Assises — a special court with jurisdiction over serious offences. In early 2015, the Cour d’Assises tried former first lady Simone Gbagbo, together with more than 75 defendants, for crimes against the state committed during the post-election crisis.[15] Simone Gbagbo was convicted and sentenced to 20 years’ imprisonment. The trial, however, did not concern the grave human rights violations Gbagbo is alleged to have committed during the crisis, and was criticized by Ivorian and international human rights groups, which said that convictions were obtained “on the basis of little persuasive evidence.”[16]

National investigations into crimes committed during the post-election crisis are conducted by the Special Investigative Cell (since renamed the Special Investigative and Examination Cell, la Cellule Speciale d’Enquête et d’Instruction, CSEI), a taskforce of investigating judges and prosecutors created in June 2011. In the first half of 2015, the CSEI charged more than 20 perpetrators—including high-level commanders from both sides of the conflict—for their role in human rights abuses during the post-election crisis.[17] However, at the time of writing there have yet to be any civilian trials or convictions of those who committed human rights abuses during the crisis.

The beleaguered Ivorian military justice system has tried a small number of pro-Gbagbo officers and soldiers implicated in killing civilians during the crisis, but has been criticized by international and local human rights groups for the lack of rigor with which it pursues these cases.[18] In March 2015, military prosecutors were forced to discontinue the prosecution of two pro-Gbagbo commanders for the indiscriminate shelling of residential areas of Abobo in March 2011, in which more than 20 people were killed, after failing to produce sufficient evidence.[19] Military courts should not, in any case, have jurisdiction over serious human rights abuses committed by the military against civilians.[20]

At the international level, the ICC began an investigation into the crimes committed during the 2010-2011 post-election crisis in October 2011.The ICC has so far brought cases against three individuals: Laurent Gbagbo, his wife Simone Gbagbo, and Charles Blé Goudé, Gbagbo’s former youth minister and close ally, and the longtime leader of a violent pro-Gbagbo militia group. The trial of Laurent Gbagbo and Blé Goudé is scheduled to begin before the ICC in January 2016, while the ICC’s Office of the Prosecutor has yet to lay charges before the court for crimes committed by perpetrators allied with Ouattara during the post-election crisis. Simone Gbagbo remains in Côte d’Ivoire as the government has refused to surrender her to the ICC.

Progress in National Courts

President Ouattara has repeatedly promised that all those responsible for atrocities during the 2010-2011 post-election crisis will be prosecuted, regardless of political affiliation or military rank.[21] He has also said all future trials relating to the post-election crisis would occur in national courts and that he would not transfer any future suspects to the ICC.[22]

The charges brought in 2015 by the CSEI against high-level perpetrators from both sides of the post-election crisis represent meaningful progress in national prosecutions.[23] The United Nations Independent Expert, as well as Human Rights Watch and other international and national human rights organizations, has publicly acknowledged the progress in the CSEI’s investigations as a significant step towards impartial justice.[24]

However, since its creation in June 2011, the Ivorian government’s financial and political support for the CSEI has been inconsistent, resulting in staffing shortages and inadequate financial resources.[25] In late 2013, the very existence of the CSEI hung in the balance, with an Ivorian government spokesman at one stage proclaiming its imminent closure.[26] Only in late 2014, after significant pressure from national and international human rights groups and diplomats, did the government provide the CSEI with the financial and material support that it needs to conduct effective investigations – a key factor in facilitating the subsequent progress in investigations.[27] Even then, in mid-2015 credible reports emerged that the CSEI faced pressure from the executive to finish key human rights investigations prematurely.[28]

Furthermore, some of the commanders that have been charged by the CSEI retain key positions within the Ivorian military, including Chérif Ousmane, commander in the Presidential Guard, and Losseni Fofana, who commands the Ivorian army in the country’s west.[29] Several international observers expressed skepticism that President Ouattara will ultimately support prosecutions of such high-level perpetrators from his side of the 2010-2011 post-election crisis.

Support for the Special Investigative and Examination Cell

It is vital that the CSEI continues to receive the resources needed to conclude its investigations.[30] Maintaining the CSEI’s staffing levels, and ensuring that the CSEI’s current investigating judges and prosecutors remain in place, is particularly important to guarantee continuity in the investigations.[31] The CSEI’s staff, as well as the Cour d’Assises judges who will ultimately hear human rights cases, would also benefit from further technical assistance on the process of trying complex human rights crimes involving multiple accused.[32]

The slow pace of national investigations underscores the importance of the ICC pursuing expeditiously its investigation of pro-Ouattara forces. Multiple interviewees suggested that the government’s increased support for the CSEI is partly motivated by a desire to strengthen the argument that Côte d’Ivoire’s courts are willing and able to prosecute perpetrators from the pro-Ouattara side (and so avoid the ICC’s jurisdiction).[33] The ICC investigation remains a vital lever to push the Ivorian government to support efforts to pursue perpetrators from both sides of the 2010-2011 post-election crisis.

Numerous international diplomats are concerned that President Ouattara will eventually pardon high-level perpetrators found responsible for crimes during the post-election crisis, with pardons for pro-Ouattara commanders offset by a similar gesture for certain high-profile Gbagbo allies.[34] President Ouattara himself said in October 2015, “We want justice to do its job. And then once that’s been done, our laws permit the consideration of amnesties and pardons.”[35]

Pardons for high-level perpetrators from either side of the 2010-2011 post-election crisis would, however, deny victims—who have now waited almost five years to see perpetrators brought to account—meaningful justice. Drissa Soumahoro, president of a coalition of victims’ groups, told Human Rights Watch that were Ouattara to grant pardons, “It would be like saying he doesn’t care at all about victims. Perpetrators must pay the penalty, and victims must have justice.”[36]

Victims’ groups also said that, while there is a need for perpetrators to seek forgiveness as part of Côte d’Ivoire’s reconciliation process, that does not diminish victims’ desire to see high-level perpetrators of human rights abuses prosecuted and, if convicted, punished. “Forgiveness doesn’t mean there shouldn’t be justice,” Soumahoro told Human Rights Watch. “We need justice—impartial justice—so that these crimes aren’t repeated.”[37] Civil society activists said that pardons for high-level perpetrators would perpetuate the cycle of impunity that has fueled Côte d’Ivoire’s past conflicts, and “would be an encouragement for recidivism by perpetrators and vengeance by victims.”[38]

President Ouattara said as recently as October 2015 that “reconciliation does not mean no justice.”[39] He should state publicly and unequivocally that he will not grant pardons to anyone convicted of serious human rights crimes. The ICC Prosecutor is likely to consider any such pardons as evidence that Côte d’Ivoire is unwilling and unable to prosecute human rights crimes at a national level.[40]

Role of the International Criminal Court

The ICC’s failure to so far bring charges against perpetrators allied with President Ouattara during the 2010-2011 post-election crisis is due to a large extent on the ICC Prosecutor’s initial decision to first investigate former President Gbagbo and his allies before moving onto pro-Ouattara forces,[41] a decision consistent with a policy of “sequencing” investigations followed by the Office of the Prosecutor in its earliest years.[42]

Court staff also told Human Rights Watch that resource constraints resulting from cases in other countries before the court have affected its ability to conduct investigations into pro-Ouattara forces.[43]

Many Ivorian civil society activists told Human Rights Watch that the one-sided focus of ICC cases to date has undermined perceptions of its legitimacy.[44] As one Ivorian human rights advocate said, “The ICC is not working to take into account all the victims… Victims that belong to the other side [victims of abuses by pro-Ouattara forces] do not believe in the ICC. It is painful to say this because normally a victim does not have a side.”[45]

The ICC investigations are also limited in their geographic scope. Laurent and Simone Gbagbo and Blé Goudé are only charged in connection with four or five incidents, all of which took place within Abidjan.[46] As a result, to date, the ICC’s cases do not address any of the atrocities committed in western Côte d’Ivoire.[47] Several community leaders in the west underscored their concern about this geographic limitation to Human Rights Watch: “Since 2002, we’ve really suffered, and yet there’s been complete impunity for all the abuses… people don’t really know what happened in the heart of the country.”[48]

The ICC’s work in Côte d’Ivoire was further complicated by public statements by President Ouattara in April 2015 that he would not transfer any future suspects to the ICC.[49] Despite in May 2015 losing an appeal over the admissibility of the ICC’s case against Simone Gbagbo (the Ivorian government argued that she could be tried in Ivorian courts), the government has refused to transfer Gbagbo to the ICC. [50]

The ICC’s Office of the Prosecutor scaled up its investigations into pro-Ouattara forces in the second half of 2015. A senior Ivorian official told Human Rights Watch that the government’s position on future transfers would not affect the Ivorian government’s cooperation with ICC investigators examining abuses by pro-Ouattara forces,[51] although one international official said that it was “too soon” to be sure about the extent of the government’s cooperation.[52]

II. Building a Justice System That Respects and Protects Rights

We need to decide what justice we want for this country. The reforms that have already been implemented are welcome, but our country, with all its resources, can do much more to facilitate access to quality justice. The reform of the justice sector can’t happen in five years, but needs a longer-term vision to accomplish meaningful change.

—Manlan Ehounou Laurent, Ivorian magistrate and president of Transparency Justice[53]

When President Ouattara assumed office in 2011, his government inherited a judicial system that had been devastated by conflict and years of neglect. His government has since made progress in repairing infrastructure and has successfully redeployed judicial personnel to areas in the north that were, prior to the 2010-2011 post-election crisis, outside of the government’s control.

Many Ivorians, however, still lack faith that the justice system will respect their rights and provide an effective remedy when these rights are violated. A December 2013 survey in Abidjan found that 64 percent of respondents have “little or no trust in the justice system.”[54] A representative of an international donor which has invested heavily in the justice sector told Human Rights Watch, “People only see court buildings as something you go to when you’re in trouble, not to get solutions to problems.”[55] An Ivorian jurist working at a legal clinic in the northeast said: “The population don’t really have confidence in the justice sector; they think that nothing will happen and the file will just sit there and there will be no action.”[56]

The Need to Rebuild

The decade of intermittent conflict and instability that followed the 1999 coup severely undermined efforts to improve access to justice, with one international donor describing the 2000s as a “lost decade” for justice sector reform.[57] From 2002, many courts did not operate in the areas in the north and west controlled by the Forces Nouvelles. Political instability and underinvestment meant that courts in the government-controlled areas were over-burdened, outdated, and inefficient.[58] The justice system was further weakened during the 2010-2011 post-election crisis, when 17 of the country’s 37 courts and 22 of its 33 prisons were damaged.[59]

Early in his presidency, President Ouattara told magistrates that there was a need to repair the “loss of confidence” in the justice system.[60] In June 2013, the government, on the basis of a proposal from the Ministry of Justice, adopted a National Action Plan for the Justice Sector, which laid out reforms envisioned to both aid the justice system’s short-term recovery and address long-standing problems, including improved judicial independence and better access to justice.[61] Pursuant to this plan, numerous court buildings and detention facilities have been upgraded.[62] Judicial personnel have been redeployed and courts reopened across the country.[63] Significant emphasis has also been placed on improving training for the judiciary.[64]

Much of the National Action Plan, however, is yet to be implemented. Ivorian lawyers and judges, as well as international donors, told Human Rights Watch that the government’s failure to implement some planned reforms, such as legislative changes to strengthen the independence of the judiciary, reflects a lack of political will; others, they said, were hamstrung by the limited budgetary allocation available for the courts and judiciary.[65]

As President Ouattara’s government begins its second term, several priority areas—discussed in more detail below—deserve urgent attention if the justice system is to adequately protect the rights of Ivorians. These notably include the lack of independence of the judiciary, corruption, excessive prolonged pretrial detention, poor prison conditions, and lack of access to legal representation.

In light of President Ouattara’s promise to revise Côte d’Ivoire’s constitution early in his second term, the government should use the constitutional reform process to bolster the independence of the High Judicial Council (Conseil Supérieur de la Magistrature, CSM) and protect judges from executive interference.

The government should also urgently review the National Action Plan for the Justice Sector to create a revised version for 2016-2020, including new target dates for the completion of key reforms not yet implemented.

The revised action plan should include a timeline for the passage of codes and laws essential to rule of law reform that were drafted during President Ouattara’s first term, but have not yet been finalized and adopted.[66] This includes the criminal procedure code and laws on the profession of magistrates, the prison system, and legal assistance.

In formulating the revised plan, the Ministry of Justice should also identify the reasonable cost of planned reforms and programs, and should advocate for increased investment in the justice sector to support key reforms. In November 2011, President Ouattara said “sufficient financial resources are essential if the justice system is to function properly,” and that he would increase the Ministry of Justice’s budget to three percent of the state budget.[67] In 2014, however, the Ministry of Justice’s budget was 90.6 million euros (US $96.4 million), just 1.4 percent of the overall budget of the Ivorian state.[68]

International donors, including France, the United States, and the European Union (EU), should apply more pressure to the Ivorian government to make progress in areas, such as improved judicial independence, where the government may lack the political will to implement reforms.[69] The French government, for example, which is currently evaluating how to invest a further 8 million euros ($8.5 million) in the justice sector, should include in its programming support for reforms to the constitutional provisions and laws governing the CSM and the profession of magistrates.[70]

Lack of Judicial Independence

Political interference in judicial decision-making in Côte d’Ivoire predates President Ouattara’s government. Ivorian government officials cite the Constitutional Court’s nullification of the 2010 presidential election results announced by the Independent Electoral Commission as reflective of the perceived lack of independence of the judicial system during the Gbagbo era.[71]

Numerous interlocutors, including Ivorian civil society groups and diplomats, expressed concerns about what they perceive as continued executive interference in the independence of the judiciary during Ouattara’s first term.[72] One Ivorian human rights activist said that the independence of the judiciary is somewhat stronger than under Gbagbo’s presidency, when the executive’s control over the judiciary was such that it was “truly justice on order.”[73] He cautioned, however, that there “remain structural problems which prevent judges from having the courage to act independently.”

Soon after taking office, President Ouattara said that his ambition was to create a justice system that was “independent and impartial.”[74] Promoting independent and impartial justice is a key pillar of both the National Action Plan for the Justice Sector[75] and Côte d’Ivoire’s National Security Strategy.[76] However, the government has failed to implement two reforms identified in the Action Plan that would protect against executive interference in the judiciary.

First, the government has not finalized a draft law that would strengthen the independence of the CSM, the body mandated to make judicial appointments and discipline judges.[77] Under the constitution, the Ivorian president is the head of the CSM, giving the executive a key role in how the institution operates. In 2012, the Ministry of Justice drafted a law that would have increased the independence of the CSM, without requiring a constitutional amendment, by requiring the president to follow the CSM’s advice when selecting judges.[78]

Similarly, the Ministry of Justice has not finalized a draft law that would modify the laws regulating the magistrate profession, which as currently applied allow the executive to determine the court to which a judge is posted.[79] A justice sector expert told Human Rights Watch that, at present, judges fear that they will be “sent to Odienné,” a particularly remote town, if they make a ruling that displeases the executive.[80]

Manlan Ehounou Laurent, the head of Transparency Justice, a group of Ivorian magistrates, lawyers, and court officials committed to improving access to quality justice, told Human Rights Watch that the government’s failure to pass a law on the CSM and the profession of magistrates had impacted negatively the independence of the judiciary. He said: “The control that the executive continues to exercise over the nomination of magistrates has significant consequences for the impartiality of judges. If I’m appointed thanks to somebody, clearly it will be difficult for me to refuse them something when they ask me to do it.”[81]

One diplomat told Human Rights Watch that the government’s failure to make progress on the laws on the CSM and the profession of magistrates was “a political decision,” which reflected a “lack of desire to change the level of control that the executive currently has over judges.”[82]

International standards require that judges be able to adjudicate cases without any improper influences, threats, or interferences, direct or indirect, from any quarter or for any reason.[83] The process used to appoint judges should safeguard the independence and impartiality of the judiciary.[84]

Prior to the October 2015 presidential election, President Ouattara said that if elected, his government would propose changes to Côte d’Ivoire’s constitution.[85] His government should use the constitutional reform process to eliminate the president’s role as the head of the CSM and establish a process for appointing members of the CSM that is independent of executive influence. The government should also revise the laws on the profession of magistrates to ensure that it is the CSM, and not the executive, that determines the courts to which judges are posted.

Corruption

Ivorian lawyers, judges, human rights organizations, and international legal experts said that corruption remains a significant problem within the judiciary, which has a direct impact on rights protection.[86] Judge Manlan, the head of Transparency Justice, told Human Rights Watch: “Corruption is part of Ivorian society, and the problems to be found in public administration, including corruption, are also found in the justice sector. But the justice sector is supposed to be society’s check and balance, and so if we’re corrupt, our society is out of balance.”[87]

Interviewees said that in criminal cases, corruption fuels impunity by allowing people with means to escape prosecution.[88] An Ivorian lawyer also told Human Rights Watch that whether an accused remains in pretrial detention in Côte d'Ivoire is often determined by what they can afford to pay. “It’s the real criminals who get out, while the poorest people stay in detention,” he said. “If you want to avoid or get out of pretrial detention, you just have to pay the prosecutor or the investigating judge and you’ll be out.”[89]

In November 2011, President Ouattara said that corruption in the judiciary “must be banished” and that corrupt judges would be fired.[90] The government and international donors have strengthened the Inspector General of Judicial and Penitentiary Services (Inspection Générale des Services Judiciaires et Pénitentiaires), the individual appointed by the government to provide oversight of the judicial and corrections services. The Inspector General’s office, having been dormant for many years, now conducts inspections of courts and prisons in Abidjan and the interior.[91] In 2012, the government also adopted rules that allow the Inspector General’s office to initiate its own investigation into a particular tribunal or official, without an instruction to do so from the Ministry of Justice.[92]

The reports compiled by the Inspector General are submitted to the Minister of Justice, who should, where there is evidence of wrongdoing by a judge or prosecutor, refer the case for disciplinary proceedings before the CSM (for judges) or a disciplinary commission (for prosecutors).[93] Ivorian jurists, however, told Human Rights Watch that they were not aware of any judges being disciplined or prosecuted for corruption since 2012, when the new rules allowing the Inspector General to initiate investigations were adopted.[94]

Ivorian and international legal experts told Human Rights Watch that, because it is the Minister of Justice who refers wrongdoers identified by the Inspector General to disciplinary proceedings, there is the potential for the executive to block disciplinary cases against judges and prosecutors.[95]

Furthermore, because neither the reports of the Inspector General nor the outcome of disciplinary proceedings against judges or prosecutors are made public, it is extremely difficult for parliamentarians and civil society organizations to provide oversight of the extent to which corruption is reported and sanctioned.[96]

In the lead up to the 2015 presidential election, President Ouattara again acknowledged that corruption is widespread in the judiciary, promising “to get to grips with it.”[97] He said that corrupt judges would be fired, and that he will propose legislation to make public disciplinary sanctions against judges.[98] This would be a positive step, although at least one Ivorian magistrate said it was important that judges accused of misconduct receive appropriate legal representation and are presumed innocent until disciplinary proceedings have been completed.[99]

President Ouattara’s new government should empower the Inspector General to refer magistrates suspected of misconduct directly to the CSM and prosecutor’s disciplinary commission, without the permission of the Minister of Justice. The government should also pass a decree requiring the Inspector General’s office to release public versions of their inspection reports, with the names of individuals suspected of wrongdoing redacted pending the completion of disciplinary proceedings. Increased public outreach is also necessary to inform the public that they can bring complaints about corrupt practices directly to the Inspector General.

Excessive and Prolonged Pretrial Detention

Ivorian courts continue to place far too many accused in pretrial detention, with approximately 40 percent of people in Ivorian jails in pretrial detention.[100] Because of the time it takes to try cases involving serious crimes, many detainees spend several years in pretrial detention before being tried or released.[101] Excessive and prolonged pretrial detention was also a severe problem during Gbagbo’s presidency,[102] but President Ouattara’s government has so far done too little to address it – doing so should be a priority for his second term.

The prevalence of pretrial detention and the slow pace of case resolution exacerbate over-crowding within Ivorian prisons.[103] Prior to the 2010-2011 post-election crisis, Côte d’Ivoire squeezed 12,000 prisoners into a national prison system designed for no more than 5,000.[104] Although prisoners escaped in massive numbers during the crisis, the prison population now varies between 8,000-12,000 detainees, with 9,500 prisoners detained in June 2015.[105] Prisoners are distributed unequally among the country’s 34 prisons, with almost half severely overpopulated.[106]

Under Ivorian law, the decision as to whether to impose pretrial detention is taken by the judge responsible for investigating the alleged crime (juge d’instruction). Although the law stipulates that pretrial detention should be an exceptional measure, it provides no guidance on the criteria judges should apply in determining whether to place someone in detention and does not require judges to provide reasons for their decision.[107]

As a result, judges too often simply decide to impose pretrial detention even if there is no compelling reason to do so. As Yacouba Doumbia, President of the Ivorian Movement for Human Rights, explains, “Because there are no guidelines as to how the decision to impose pretrial detention is determined by the investigating judge, pretrial detention becomes the rule and not the exception as provided for by the criminal procedure code.”[108] International human rights law makes clear that pretrial detention should be the exception, not the general rule.[109]

In July 2013, the Ministry of Justice, pursuant to the National Action Plan for the Justice Sector, established an expert committee to reform the country’s legal codes.[110] The subcommittee examining the criminal procedure code in 2015 drafted provisions that would specify the grounds according to which a judge can impose pretrial detention and would require judges to provide reasons for doing so. The revised code would also permit judges to impose conditions on defendants released prior to trial, such as the requirement to periodically check in at a police station.[111] The Ministry of Justice should expedite the review and adoption of the committee’s proposed changes to the criminal procedure code.

To address the slow pace of justice that contributes to prolonged pretrial detention, the Ministry of Justice, with support from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), has developed and piloted an improved case management system to help courts track the progress of criminal cases.[112] However, efforts to expedite cases are often undermined by the requirement that individuals accused of a serious crime, such as murder or rape, can only be tried before a Cour d’Assises, a specially convened court with 3 judges and a 6-person jury.[113] Under Ivorian law, the Cour d’Assises is required to convene every three months.[114] However, despite the backlog of cases, the logistical and financial challenges associated with convening the Cour d’Assises mean that it meets very irregularly – Côte d’Ivoire held its first Cour d’Assises sessions in 10 years in 2014.[115]

International human rights law requires that anyone who is arrested or detained on a criminal charge shall be entitled to trial within a reasonable time or to release.[116] One option to reduce delays in the adjudication of serious criminal cases would be the creation of a permanent criminal chamber within Côte d’Ivoire’s three courts of appeal, a change that has yet to be integrated into the ongoing reform of the criminal procedure code.[117] The criminal procedure code should also establish time limits within which courts should hear criminal cases, with an accused released from pretrial detention and given compensation if held beyond the time limits.[118]

Prison Conditions

According to Ivorian NGOs and international experts working on prison reform in Côte d’Ivoire, prisoners routinely lack adequate nutrition, sanitation, and access to medical care.[119] Some prisons, such as the civil prison in Bouaké, fail to separate adult and juvenile detainees.[120] To its credit, the Ministry of Justice’s Direction of Prison Administration (Direction de l'Administration Pénitentiaire, DAP) has acknowledged the problems facing the prison system and in 2015 elaborated a draft Plan to Improve Prison Conditions (Plan d’ Amélioration des Conditions de Detention) to address overcrowding, improve hygiene, healthcare, and nutrition, and increase access to legal and social services. The DAP has also said that it will regularly convene a workshop with civil society organizations to discuss progress.[121] Implementing the plan will, however, require a significant increase in the budget allocated to the Ivorian prison system, something that multiple justice sector experts told Human Rights Watch would be difficult to achieve within the Ministry of Justice’s current budget.[122]

The Ministry of Justice is also in the process of drafting a new law on the prison system as well as decrees that would specify how the law should implemented. In finalizing this law and decrees, the Ministry of Justice should consider innovations—such as imposing probation as an alternative to custody—that would ease prison overcrowding.[123]

Lack of Access to Legal Representation

The lack of legal representation for the accused in criminal cases is a key factor contributing to excessive and prolonged pretrial detention, and also compromises the fairness of defendants’ eventual trials.[124]

Under Ivorian law, defendants only have access to mandatory legal representation for cases going to trial before the Cour d’Assises, which deals with the most serious criminal cases.[125] For indigent defendants, the Cour d’Assises is required to appoint a lawyer, who receives a set fee provided by the state.[126] Those tried for lesser crimes outside the jurisdiction of the Cour d’Assises are only represented if they can pay for a lawyer, which many litigants cannot afford.[127] There are approximately 500 lawyers active in Côte d’Ivoire—all but a handful based in Abidjan—making it particularly difficult for those in the interior to obtain legal representation.[128]

That indigent defendants accused of crimes before the Cour d’Assises often only receive legal representation at the trial phase severely affects the fairness of the proceedings. Because key decisions in the case—such as which witnesses are interviewed by the investigative judge—occur during the investigative phase, one Ivorian lawyer told Human Rights Watch, “To have a lawyer at the Assises trial, but not during the investigation, is pointless.”[129] International human rights law requires that defendants receive the assistance of a lawyer from the time of arrest.[130]

Indigent defendants who want legal representation before their case reaches the Cour d’Assises, or who are charged with less serious offenses, must rely either on Côte d’Ivoire’s flawed legal aid system, which is supposed to help indigent litigants in all civil and criminal cases, or nongovernmental organizations (NGOs).[131] However, an Ivorian jurist and an international legal expert said that very few litigants in Côte d’Ivoire know about the possibility of obtaining legal aid, or the procedure for doing so, and the National Legal Aid Bureau, the Ministry of Justice office in Abidjan that adjudicates these requests, receives only a few hundred each year.[132]

In the absence of adequate state-supported legal aid, much of the burden for providing legal representation has fallen on NGOs. During President Ouattara’s first term in office, the EU and the UN supported the opening of six legal clinics in the country’s interior by the Association of Women Jurists for Côte d’Ivoire (Association des Femmes Juristes de Côte d’Ivoire, AFJ-CI).[133] As Aimée Zebeyoux, President of AFJ-CDI, explained to Human Rights Watch: “The clinics are designed to make justice more accessible. We’re trying to reassure litigants who are scared to approach the justice system without our help.”[134]

Although several interviewees said that the NGO-run legal clinics provided essential services, the responsibility for providing legal assistance to indigent Ivorians, particularly in criminal cases, lies with the Ivorian government.[135] In early 2014, the UN Operation in Côte d’Ivoire (ONUCI), the EU, and a USAID-funded program jointly drafted and proposed a new law on government-provided legal assistance that sought to make legal aid more accessible by creating state legal aid offices within every first instance court (both tribunaux de première instance and sections detachées).[136] The law, however, remains under review within the Ministry of Justice.[137] The Ministry of Justice has also so far been reluctant to commit its own funding to supporting legal aid.

III. Reforming the Security Sector

For 10 years, there was no police, no government, no justice… No one was concerned with human rights. We are now trying to reestablish the rule of law here.

–Police commander, northern Côte d’Ivoire[138]

Several interlocutors told Human Rights Watch that the conduct of the security forces, including the military, had improved since the 2010-2011 post-election crisis. One senior ONUCI official said that the Ivorian army is “less the brutes towards the population that they used to be.”[139] The government has also made progress in transferring law enforcement responsibilities from the armed forces to police and gendarmes, although they often lack sufficient equipment and training to protect citizens from criminality.

Despite the progress made, however, ongoing violations by security forces, including arbitrary arrests and detentions, and, in some cases, torture, continued during President Ouattara’s first term in office.[140] Racketeering and extortion, predominantly at illegal checkpoints, remain widespread among all branches of the security forces, including the police and gendarmerie.

ONUCI officials, Ivorian police officers, and civil society activists told Human Rights Watch that members of the security forces are very rarely criminally prosecuted or sanctioned for human rights abuses by either the civilian courts or the military justice system.[141] When soldiers are prosecuted in civilian courts, one Ivorian jurist said that, “Too often, because it’s the military, the cases don’t go anywhere.”[142] Côte d’Ivoire’s military justice system is severely under-resourced and is in urgent need of reform to make it independent from the executive.

A Legacy of Abuses