For the past decade, Mexico has pursued a “war on drugs” with catastrophic consequences — drug-related violence has taken the lives of tens of thousands of people. Last month, the Supreme Court of Mexico ruled that prohibiting the personal use of marijuana violates a constitutional right to the “free development of one’s personality.” The ruling, while limited to marijuana, represents an important step toward a new approach to drug policy that could help make Mexicans healthier and safer.

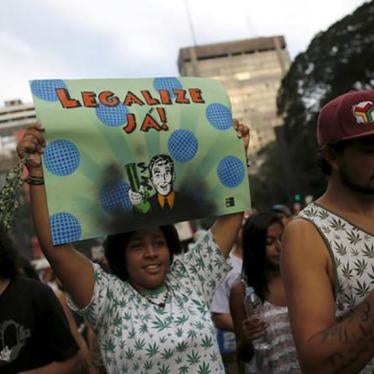

We hope that Brazil´s Supreme Court will follow Mexico’s example. The Brazilian court is considering whether a law that makes possession of drugs for personal use a crime violates a constitutional right to privacy. If the court strikes down the law, Brazil will join a growing list of countries that are liberalizing their policies toward drug use – from Portugal, which in 2001 decriminalized the personal use of all drugs without apparent ill effect, to Uruguay, which in 2013 became the first country fully to legalize and regulate marijuana.

Even the United States, traditionally one of the most zealous enforcers of a prohibitionist approach to drug control, is starting to soften. Almost half of its 50 states have legalized marijuana in some form, and the Obama administration is taking a hands-off approach to the states’ experiments.

The changes reflect a rising recognition that while governments have a legitimate role in minimizing the harm that drugs cause, criminalizing personal use is wasteful, counterproductive, and incompatible with respect for human rights. When people under the influence of drugs endanger others — whether driving a car, neglecting a child, or snatching a purse — criminal sanctions may be entirely appropriate. But the punishment in these cases should be for the harm done to others, not to oneself.

Brazil would benefit by making a distinction between personal drug use and the anti-social behavior that it may cause. In places where possession and use is legal, money that would otherwise be spent prosecuting and incarcerating non-violent users can be diverted to treatment centers — and with the threat of criminal prosecution lifted, drug-dependent people need not fear seeking help at clinics.

Both Mexico and Brazil have already tried tinkering with drug laws to divert users who aren’t traffickers to treatment or community service instead of prison. But both Brazil’s law, passed in 2006, and Mexico’s, passed in 2009, also stiffened penalties for small-scale trafficking and gave police, prosecutors, and judges little guidance on how to distinguish between traffickers and users. So it’s impossible to know how many Mexicans or Brazilians who are serving prison time on drug charges were simply non-violent users wrongly charged as traffickers. In Mexico, the Supreme Court’s marijuana decision last month included a recognition that allowing users to grow their own protects them both from prosecution and from the risks inherent in buying from criminals.

Legalizing the possession of drugs for personal use in Brazil would probably help alleviate the country’s chronic prison overcrowding, and it would certainly allow a fresh approach to the problems of drug dependence. Inside Brazil’s prisons, drugs can be easy to get, and drug treatment is not often available, Human Rights Watch research has found.

Brazil’s Supreme Court in September put off deciding whether the law that makes possession of drugs for personal use a crime violates Article 5 of the Constitution, which guarantees a right to privacy. That right is also enshrined in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the American Convention on Human Rights. An affirmative decision in the case would not only represent long-overdue recognition of personal sovereignty, it would provide an opportunity to pivot toward managing drug dependence as an illness instead of a crime.

The United Nations General Assembly is planning a special session on drug policy in 2016, giving Brazil a chance to assume a leadership role in diverting resources from prosecution of users to treatment of those who are drug-dependent. Brazil should step into that role. After all, as the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs put it in 1961, the purpose of drug policy is “the health and welfare of mankind.”