Presidential and parliamentary elections are set for early 2016, in what will be President Yoweri Museveni’s 30th year in office. Mbabazi, his long-time ally and former prime minister, has broken with the ruling party to run against Museveni. Another opposition presidential aspirant, Kizza Besigye, has been arrested numerous times, most recently on October 15, for allegedly seeking to hold public rallies. The official presidential campaigns are to begin on November 9.

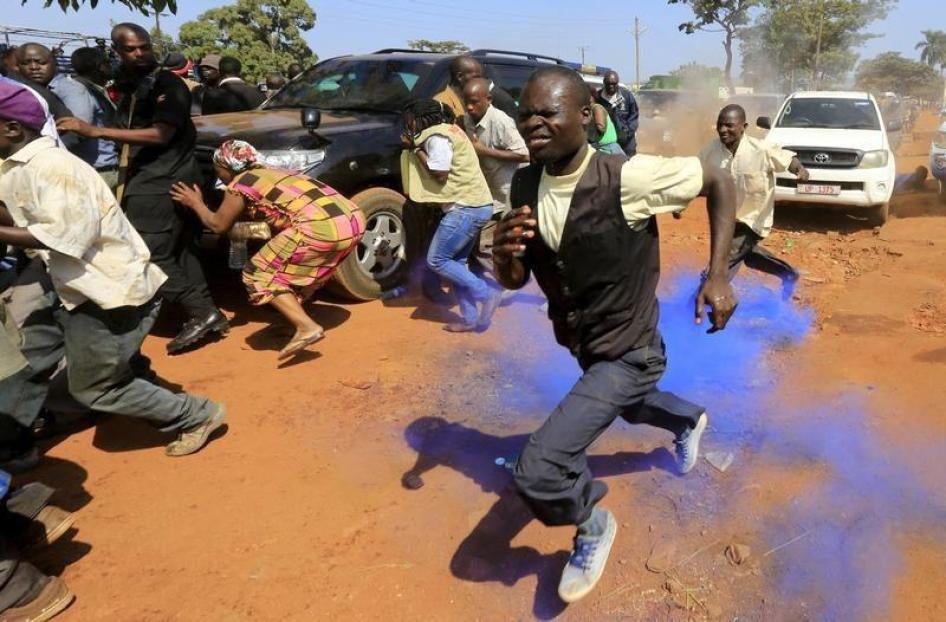

In interviews about the September rallies, witnesses from each location told Human Rights Watch that the gatherings were generally peaceful and had barely begun when police arrived and released teargas. In some cases, the candidate had not yet arrived. Dozens of people said they were injured or felt ill from the teargas, and some were injured by rubber bullets and police beatings.

Teachers at the Main Street Primary School in Jinja reported that police fired three canisters of teargas into the school grounds, stinging the young students’ eyes and faces. “Hospitals and schools aren’t supposed to be attacked,” a teacher said. “They’re children, innocent kids. They’re not supposed to be attacked.”

A restaurant worker in Jinja’s Kazimingi Industrial Park told Human Rights Watch that her three-year-old daughter had lost consciousness after inhaling large amounts of teargas. The mother rushed the child to medical officers who confirmed that her daughter was suffering the effects of teargas.

At a rally on September 9 in Soroti sports grounds, police in riot gear used teargas and shot rubber bullets at civilians. Several witnesses said the police gave no warning and there had been no disorder before police arrival. The police fired teargas canisters under an NTV news vehicle, forcing journalists to take cover inside. Some people at the rally eventually threw stones and unexploded teargas canisters toward police.

Human Rights Watch spoke to eight journalists who were injured while covering the events. The injuries included contusions, and in one case a rubber bullet wound. Journalists also had difficulty breathing due to the teargas. One print journalist said that as he left for his office to write his news story about the day’s events, two police officers openly threatened him, with one officer pointing his teargas gun directly at the journalist until he fled.

In 2009 and 2011, police used live ammunition to disperse people at several opposition gatherings, as well as at rallies and demonstrations against government actions, killing at least 49 bystanders and protesters.

In early 2014, a coalition of opposition and non-governmental organizations began a countrywide campaign called “Free and Fair Elections Now!” about the importance of electoral reforms. In Mbale on March 22, 2014, and in Soroti on the following day, police used teargas to forcibly disperse people peacefully gathered to listen to opposition politicians from several parties. According to the United States State Department, several people were injured when police used teargas in Mbale.

Ugandan police use several justifications for forcibly dispersing people at opposition gatherings, citing violations of various laws as a basis to use teargas and unleash violence. The Public Order Management Act (POMA), passed in August 2013, grants the Inspector General of Police wide discretion to permit or disallow public meetings. Opposition leadership argue that police routinely do not respond when they are notified or deny opposition requests to hold gatherings. In some instances, opposition organizers have been told on the day of the event that the site is no longer available.

The Electoral Commission stated in September that political rallies are currently unlawful because the campaign has not officially started in accordance with the Presidential Elections Act. The Commission argued that “[s]ome aspirants are turning consultative meetings into open campaigns and rallies contrary to the law.” However, Museveni routinely speaks and attends public events and communicates with voters about his political intentions. As one journalist noted, “There is selective application of POMA. When it is [the ruling party] nobody bothers to notify police.”

Under the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights, to which Uganda is a party, every potential voter in Uganda is guaranteed “the right to receive information.” Similarly, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) cites “the freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds.” Police actions in the context of these public gatherings violate the right to free assembly and right to free expression, denying opposition political groups and potential voters the ability to communicate on a range of issues, Human Rights Watch said.

Under international law, the freedom to take part in a peaceful assembly is of such importance that an unlawful but peaceful situation does not justify an infringement of freedom of assembly. In instances in which there are no acts of violence, public authorities should show tolerance toward peaceful gatherings for freedom of assembly to have real meaning.

Both the African Charter (article 11), and the ICCPR (article 21) provide that no restrictions can be placed on freedom of assembly other than those imposed in conformity with the law and that are necessary in a democratic society in the interests of national security or public safety, the protection of public health or morals, or the protection of the rights and freedoms of others. Any general prohibition on political rallies taking place except during a very short period set by the authorities does not meet the necessary standards and is incompatible with freedom of assembly.

As a riot-control method, teargas should be used only when necessary as a proportionate response to quell violence. It should not be used in a confined space, and canisters should not be fired directly at any individual, and never at close range. International guidelines, such as the United Nations Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms, stipulate that the police are expected to use discretion in crowd control tactics to ensure a proportionate response to any threat of violence, and to avoid exacerbating the situation.

The Ugandan Police Force should draw up guidelines on the use of teargas, Human Rights Watch said. The guidelines should be unambiguous that teargas may not be used simply because police deem a gathering unlawful, including when police believe organizers have failed to comply with the Public Order Management Act’s requirements regarding police notification or permission.

Uganda’s key development partners, such as the US, UK, the European Union, and Ireland – some of whom have directly supported public order management and community policing programs in recent years – should publicly support a call for guidelines on the use of teargas in compliance with international law. They should also publicly call for police to respect freedoms of assembly and expression throughout this critical campaign time.

“Police should be protecting the right of all Ugandans to hear and debate a variety of issues as the 2016 election looms, no matter the political inclinations of the gathering,” Burnett said. “Instead they are unlawfully interfering with basic freedoms through the reckless use of teargas, damaging the outlook for a free and fair election in a few months.”