Fighting rocked Côte d’Ivoire after its 2010 presidential election, when the country’s then president, Laurent Gbagbo, refused to step down in favor of current President Alassane Ouattara. The country descended into five months of violence, with the conflict waged along political and sometimes ethnic and religious lines. At least 3,000 people were killed and 150 women raped, with abuses committed by both pro-Gbagbo and pro-Ouattara forces.

In October 2011, the International Criminal Court (ICC) prosecutor opened investigations into the violence. Although the ICC prosecution committed from the outset to investigate both sides – and says it still plans to – it has so far only opened cases for crimes allegedly committed by forces allied to Gbagbo, including Gbagbo himself. This move has led to dangerous perceptions of a biased court, left many victims of the fighting without a sense of justice, and made it difficult for ICC staff to disseminate information. Elizabeth Evenson, senior international justice counsel at Human Rights Watch, speaks with Elly Stolnitz about the new report, “Making Justice Count,” what the ICC needs to do – not just in Côte d’Ivoire but also in other countries – and how it can better deliver justice in The Hague that matters to victims on the ground.

How did the investigation become one-sided?

The prosecution said that it planned to investigate all sides. But, it decided to initially focus on crimes allegedly committed by pro-Gbagbo forces.

This initial decision turned into years of delay. The office of the prosecutor says that it ran into resource problems – it didn’t have money to do additional investigations because it had to prioritize investigations in other cases. The prosecution says that it plans to push forward with more investigations in Côte d’Ivoire later this year, which could mean a fresh chapter for the ICC in the country. But in the meantime it has been almost four years of being seen to be prosecuting only one side.

What does this all mean for people in Côte d’Ivoire?

Not bringing cases to address crimes by all sides is preventing victims of crimes committed by pro-Ouattara forces from obtaining justice before the ICC against perpetrators. In 2011, when the ICC first opened investigations, it was clear that Ivorians had high expectations for the ICC. Now, in my research for this report, these issues of perceptions of bias or one-sided justice came up in almost every interview. This really threatens to undermine the court’s legitimacy with many people in Côte d’Ivoire, especially victims of abuses committed by pro-Ouattara forces.

What should the court have done differently?

There are different things that different parts of the court needed to do and should be doing in other countries where the ICC has opened investigations.

The prosecutor has to make really difficult decisions about who to prosecute – she can’t investigate all the crimes committed in a conflict. But that means the cases her office does prosecute need to try to create as much impact as possible. The prosecution should have better reflected what happened to victims, across the conflict. Going forward, in Côte d’Ivoire and in other countries where the ICC is investigating, we think the prosecution should do more to put into practice its standing commitment to consult more with victims as part of making decisions about whom to prosecute and for what. Otherwise, if cases don’t better reflect the experience of more victims, ultimately, the court can seem irrelevant to victims and communities in the countries where investigations are conducted.

But other parts of the ICC needed to do more to engage Ivorians across the board. For three years, the ICC Registry, in charge of the court’s outreach, had no one based in Côte d’Ivoire whose job was to provide information to people and to journalists about the proceedings. They did what they could from The Hague, but didn’t have the resources to have someone in Abidjan fulltime. So in the end, not enough people got the information they needed.

There’s a lot of awareness of the ICC in Côte d’Ivoire because a former president is on trial. But the ICC can be very difficult to understand – why did the prosecution make the choices it made, which victims can access rights before the court – and the ICC hasn’t been able to provide that kind of information to a broad enough set of people.

The court did do a lot of work with journalists, too – providing trainings, bringing some Ivorian journalists to The Hague to cover proceedings. But the Ivorian press – particularly the newspapers – often reports along party lines. The ICC really needs to have its own programs to talk to people directly.

Fortunately, the ICC Registry realized this shortfall and last October they hired a fulltime outreach person for their Abidjan office. Next year, under broad reforms planned by the ICC Registry, they should have a head of the office in Abidjan. That should also help the Registry to be more strategic in how it approaches outreach and other activities in the country. Hopefully, the information they provide will help more people understand the ICC.

What does this mean for civil society?

Civil society organizations in Côte d’Ivoire are a vital bridge between victims and the court. Civil society has stepped into the breach, to raise awareness about the ICC and update people on the ICC proceedings. And while civil society organizations have been supported in their activities by the ICC to a certain extent, Ivorians’ perception of the court as one-sided makes their work difficult.

The ICC is so important to these activists. They want the court to succeed and for people to be held accountable so the country can move on. I spoke with a coalition of activists who put the ICC in touch with local journalists, rented conference rooms for ICC press conferences, and set the ICC up to work when investigations were first opened. Then the ICC never fully took over with its own strong, outreach activities. To me, it felt like it really left these activists hanging.

These activists even traveled to small towns in western Côte d’Ivoire, where many people hadn’t seen any justice from the ICC. “They didn’t want to listen to us,” one of them told me. “But when we took the time to explain the situation to them, some understood it.”

The ICC should work closely with civil society but it needs to be doing a lot of this work itself. With someone now in the country fulltime, they will have more capacity to do it.

Tell me more about the court’s funding problems.

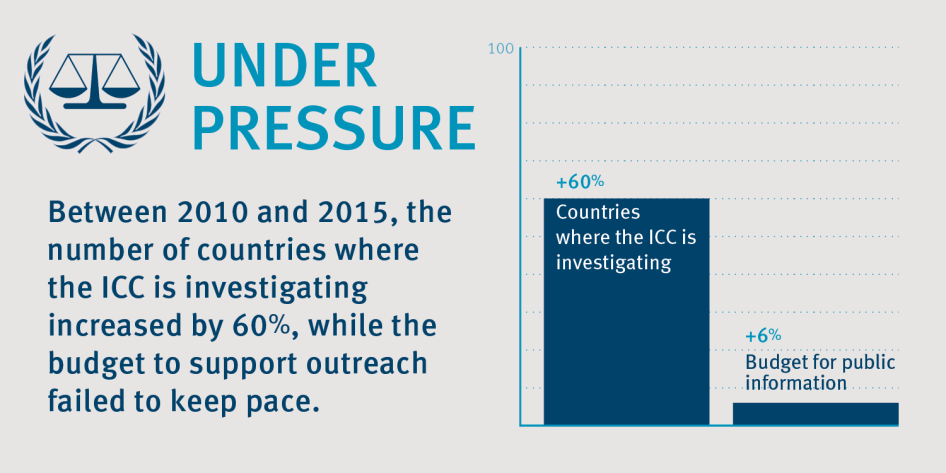

Money shortfalls are the backdrop for many of the court’s decisions we saw in Côte d’Ivoire. This is particularly true for its outreach activities – the court told us they really didn’t have the money to have done things differently. And we’ve seen this shortfall in outreach in other countries where the ICC is investigating, too.

When it comes to investigations, a lack of sufficient resources is definitely becoming more and more of a problem. As Côte d’Ivoire shows, it isn’t enough to do one case, about a limited set of crimes, to make justice count locally. This is something that has also been clear from the prosecution’s work in many other countries, like Congo, like Libya. As the number of places where the ICC is investigating increases, it is important that it have the resources it needs to bring to court cases that will resonate with local communities, and cases that address underlying patterns of crimes that have been committed.

Sometimes I get the feeling that the court only has enough funding to put out fires, rather than to execute a solid strategy, whether in terms of what cases to bring or how to really make sure the court’s work is accessible and meaningful for local communities.

Who funds the court?

The 123 countries that belong to the Rome Statute, which brought the ICC into existence. All the countries agree on the budget each year, and then pay according to their means based on a scale initially set by the United Nations. A few years back – when some of the decisions we talk about in this report were being made – countries including the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, and Japan were putting a lot of pressure on the ICC to hold down costs. For several years, there have been no significant increases in funding for outreach activities. Some of that pressure on the budget has eased up, but Canada is continuing to insist that there be no growth in the ICC’s overall budget.

This isn’t surprising – countries everywhere are facing economic problems – but as a result the ICC is getting more and more overstretched.

The problem of limited impact on the ground isn’t just about money, of course. But the court currently has investigations ongoing in eight countries, and is fielding more investigation requests. Meanwhile, it isn’t like the court has the resources it needs to fully support better impact on the ground, even where it is already investigating. It’s likely that the court will need increases in some key areas to be more effective.

How will this affect the perception of the ICC in Africa?

In Côte d’Ivoire, it was the government that asked the ICC to step in. However, at the time Côte d’Ivoire wasn’t an ICC member country, so the prosecution actually had to open what is known as a proprio motu investigation, that is, of its own motion. In five of the eight countries where the ICC is conducting investigations, it has been at the request of the government. So even though the ICC gets criticized for being too focused on Africa, the reality is that it is providing a justice for victims that African governments want. There have been real efforts to paint the ICC as unfairly targeting African leaders. Some of this comes from leaders who fear they may end up in the dock at the ICC. Some of this no doubt reflects the reality that there are double-standards – leaders of powerful countries are still less likely to face justice. Those are double-standards we should work to erase, but they aren’t a reason to stop the ICC from providing justice where it can.

I am not sure if the political debates on the ICC among certain African leaders are really connected up with what the ICC is doing on the ground. But perceptions of bias in the cases the ICC prosecutor chooses don’t help, and the better the ICC’s work is – the more it is seen to really address the experiences of victims through its cases and to make proceedings accessible to more people – the faster it should be able to close down accusations made by critics.

What’s next? What do you want to see happen?

There are positive changes underway at the ICC. Across its leadership, there is a willingness to pay more attention to its impact on victims. The court is making some changes to how it works on the ground. We think for the Registry, in particular, that should be an opportunity for it to step back and consider how it can go about its work – providing outreach, talking to victims – in a way that maximizes impact. The ICC prosecutor should apply these lessons learned from Côte d’Ivoire to the court’s policies and practices. They have already stepped away from sequentially investigating different sides to a conflict in other countries, and that’s a positive. The prosecutor should look for ways to get more input from victims at early points in her investigations, which could help close the gap between what the ICC is delivering and what victims are expecting.

Also, ICC member countries need to understand what it really takes for the court to have impact on the ground. Impact, of course, requires fair trials that get at the truth of what happened, but it doesn’t just mean getting arrest warrants and bringing cases in front of judges – it also means that court proceedings are meaningful and accessible to victims and communities where the crimes happened. If you look at what the ICC is doing from the narrow lens of what happens in The Hague, you’re missing the point.

This interview has been edited and condensed.