(Dakar) - Well-armed criminal gangs in western Côte d'Ivoire subject local residents to a relentless stream of abuses, including assault, robbery, and sexual violence, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today. The Ivorian authorities, who have failed to prevent or respond to the violence, should undertake patrols in hard-hit areas, investigate and prosecute crimes, and punish members of security forces who have failed to protect the population.

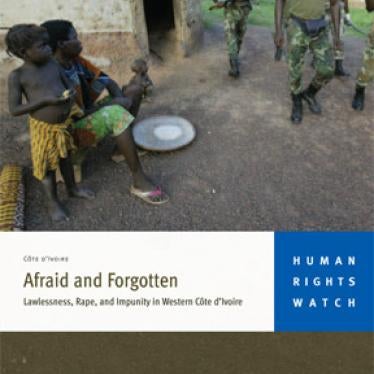

The 72-page report, "Afraid and Forgotten: Lawlessness, Rape, and Impunity in Western Côte d'Ivoire," documents the often brutal physical and sexual violence in the western administrative regions of Moyen Cavally and Dix-Huit Montagnes. The widespread criminality has been fueled by the disintegration of legal institutions, a failed disarmament process that has left the region awash with arms, and state officials' refusal to respond to attacks.

After repeated postponements in organizing presidential elections over the last five years, Ivorians are finally scheduled to go to the polls on October 31, 2010. Presidential candidates should address how they will respond to these human rights issues and re-establish functioning judicial institutions throughout the country, Human Rights Watch said.

"While politicians and foreign diplomats have wrangled over election preparations, residents in western Côte d'Ivoire are consumed by fear of violent robbery or of being pulled from a bus and raped," said Corinne Dufka, senior West Africa researcher for Human Rights Watch. "Improving this shameful state of affairs should be an urgent priority for whoever wins the election."

The report is based on interviews with more than 80 victims and witnesses of violence and extortion, as well as government officials, law enforcement and military personnel, rebel soldiers, representatives from the United Nations and nongovernmental organizations, and diplomats.

An armed conflict in 2002 and 2003 pitted government forces and government-supported militia - 25,000 in Moyen Cavally alone - against the Forces Nouvelles, or New Forces, an alliance of rebel factions from the north and west. Due to the proliferation of both arms and irregular combatants in the region, the west was the hardest hit area by the conflict.

A ceasefire in May 2003 marked the formal end of hostilities, followed by several peace agreements spearheaded by France, the regional body ECOWAS, the African Union, and the United Nations. The country remains divided, however, with the government largely failing to re-establish control in areas across the country or to rebuild institutions. The UN Operation in Côte d'Ivoire (UNOCI) remains in the country with 8,400 personnel, while a UN arms embargo, a French peacekeeping force, and other measures are still in place to help keep the peace.

Daily Existence Marked by Fear

Criminal gangs in western Côte d'Ivoire regularly attack residents in their homes, as they work their fields, and as they walk to market or travel between their villages and the main regional towns. The attacks peak on weekly market days, when village women converge to buy and sell goods, and during the cocoa harvest, November through March.

Bandit groups, known as coupeurs de route, establish makeshift roadblocks and then surround their victims as they walk to market or travel on transport vehicles. Almost always masked, these gangs are armed with Kalashnikov rifles, hunting rifles, long knives, and machetes. Attackers work meticulously, often stripping their victims to find every last coin, inflict physical abuse and, at times, kill those who refuse to relinquish money or who try to identify the attackers.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 10 drivers of public transport vehicles in the west who had, among them, been victims of 17 attacks on the road between November 2009 and July 2010. They provided examples of dozens of similar attacks on other drivers.

In the course of these attacks, hundreds of women and girls have been sexually assaulted, raped, or gang raped. In interviews with victims and witnesses, Human Rights Watch documented 109 cases of rape in Moyen Cavally and Dix-Huit Montagnes since January 2009, and the total number of victims is most likely much higher.

The assailants routinely pull women and girls off of trucks, one by one, march them into the bush, and rape them while other bandits stand guard. Human Rights Watch documented several attacks in which armed men raped more than a dozen women and girls whom they had forcefully removed from transport vehicles. In one single episode in January, at least 20 women and girls were raped. During home attacks, criminal gangs tie up husbands and force them to watch the attackers rape wives, daughters, and other female family members. The bandits have also targeted very young children, including babies, and women over 70.

A 32-year-old woman described one such attack as she and four other women returned from market in January:

"We were far from my house in the forest; I was with my baby when [the bandit] stopped us in the middle of the road. They caught me and they said, ‘Take off the baby,' and they took my baby and threw him on the ground. They beat me and beat me with the end of the Kalash [Kalashnikov rifle]. My baby was in the bushes and they raped me.... After they finished I went to pick up my baby. They beat me, and again my baby fell down."

Residents inhabit a world of fear because of the frequency of these attacks; for many, this fear has severely undermined their livelihood and led to significant lifestyle changes. Others simply live with the dread that an attack may occur the next time they or a loved one walks to market or travels to sell cocoa. Travel at night is impossible in most areas, but the daytime is scarcely better. Terrified of repercussions for speaking about the attacks, victims and witnesses interviewed for the report often refused to divulge even their first names, while others looked around repeatedly during interviews, saying that "nowhere is safe."

"The cocoa harvest, the most important economic activity for many Ivorian families, starts soon," Dufka said. "Ivorian authorities, along with the UN peacekeeping force, should take urgent measures to step up their patrolling to prevent a five-month nightmare for the people of the far west."

Inaction and Abusive Behavior by Ivorian Authorities

The government of Côte d'Ivoire has failed to protect people in the west, despite residents' pleas for help. Victims' requests for protection from immediate danger and reports of crimes to the police or gendarmes are met with inaction or, in many cases, attempts at extortion.

Dozens of victims, including drivers, passengers, and women and girls who had been raped on transport vehicles, described going to police and gendarme checkpoints - ostensibly established by the government to provide security in high-crime areas - immediately after an attack and asking police and gendarmes to pursue the attackers. Victims universally described being met with scant interest or dismissive responses and, in almost every case, the police or gendarmes refused to move from their checkpoints or to call or radio in for reinforcements.

In one case, a group of five women who had escaped on foot from an attack by armed men and made it to a checkpoint reported to gendarmes that four other women were still being held. The women pleaded with authorities to rescue their friends, but said the police told them, "It's not our job; our job is only to guard the checkpoint."

In another case, a driver told Human Rights Watch that he implored security forces to pursue bandits who had just attacked his vehicle carrying 20 passengers a few kilometers away. The gendarmes never moved, and, in front of a young girl who had just been raped, said dismissively, "You're lucky there aren't any dead among you."

Compounding the lack of access to justice, in dozens of cases documented by Human Rights Watch, victims of violence in both Moyen Cavally and Dix-Huit Montagnes said that the police or gendarmes demanded money when victims filed complaints. Those who openly engage in extortion rarely face punishment and, in some cases, their superiors are directly implicated in profiting from this racket.

The rare investigated case is adjudicated in a system fraught with deficiencies, including inaccessible courts, corrupt and absent judicial officials, and nonexistent witness protection programs. Meanwhile, striking deficiencies in the prison system, including corruption and insufficient facilities and guards, have led to the premature or illegal release of alleged perpetrators who are on remand or even convicted criminals. Once released, these individuals are free to take revenge on their victims for reporting them.

Moreover, Ivorian security forces and Forces Nouvelles rebels in the north are implicated in widespread extortion, small- and large-scale racketeering, and other human rights abuses. In the government-controlled region of Moyen Cavally, police and gendarmes use their checkpoints to demand bribes for passing through, crippling the livelihoods of drivers, merchants, and market women. Perceived immigrants are targeted for particularly severe extortion and are often taunted, robbed, and physically assaulted if they refuse to pay.

In Dix-Huit Montagnes, a region still largely under the de facto control of the Forces Nouvelles, rebel soldiers fan out to checkpoints, businesses, and market stalls and demand money, using intimidation and violence to enforce their demands. Human Rights Watch found that in Dix-Huit Montagnes alone, the Forces Nouvelles extort the equivalent of tens of millions of US dollars each year, largely from those involved in all chains of the cocoa and timber industries.

"Police and security forces have utterly failed to protect the population of western Cote d'Ivoire from the horrific banditry of these criminal gangs," Dufka said. "The government urgently needs to improve its response to this utter lawlessness, which is wreaking havoc on the lives of the local population."