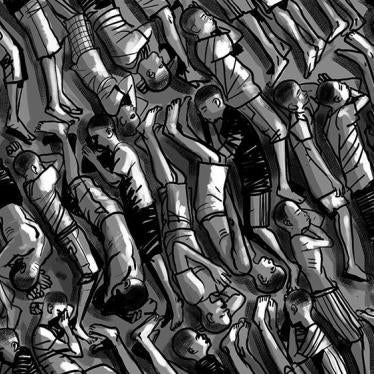

(Abuja) – Attacks by the Islamist armed group Boko Haram killed more than 1,000 civilians in 2015, based on witness accounts and an analysis of media reports. Boko Haram fighters have deliberately attacked villages and committed mass killings and abductions as their attacks have spread from northeast Nigeria into Cameroon, Chad, and Niger since February.

Human Rights Watch interviews in late January with people who fled Yobe, Adamawa, and Borno states in northeastern Nigeria revealed horrific levels of brutality. Since mid-2014, Boko Haram fighters have seized control of scores of towns and villages covering 17 local government areas in these northeastern states, some of which were recaptured by Nigerian and Chadian forces in March 2015.

“Each week that passes we learn of more brutal Boko Haram abuses against civilians,” said Mausi Segun, Nigeria researcher at Human Rights Watch. “The Nigerian government needs to make protecting civilians a priority in military operations against Boko Haram.”

The findings underscore the human toll of the conflict between Boko Haram and forces from from Nigeria, Cameroon, Chad, and Niger. Nigeria’s National Emergency Management Agency says that nearly one million people have been forced to flee since the Islamist rebel group began its violent uprising in July 2009. During 2014, Human Rights Watch estimates that at least 3,750 civilians died during Boko Haram attacks in these areas. Attacks in the first quarter of 2015 have increased compared to the same period in 2014, including seven suicide bombings allegedly using women and children.

The group also abducted hundreds of women and girls many of whom were subjected to forced conversion, forced marriage, rape, and other abuse. Scores of young men and boys were forced to join Boko Haram’s ranks or face death, according to Human Rights Watch research. Hundreds of thousands of residents were forced to flee the area, either because Boko Haram fighters ordered them to leave or out of fear for their lives.

Displaced people told Human Rights Watch they had fled with only the clothes on their backs after witnessing killings and the burning of their homes and communities by Boko Haram, and in one case by Nigerian security forces.

“As bombs thrown up by Boko Haram started exploding around us on the hills, I saw body parts scatter in different directions,” one witness of attacks in the Gwoza hills in Borno State told Human Rights Watch in late January. “Those already weakened by starvation and thirst coughed repeatedly from the smoke of the explosions until they passed out… I escaped at night.”

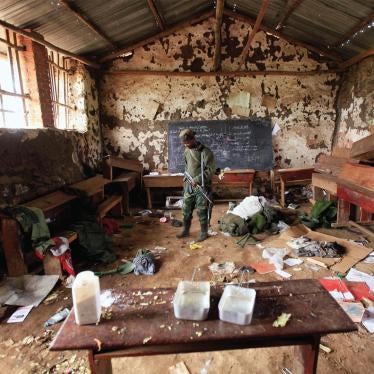

Displaced people also described targeted burning of schools by Boko Haram, and a few instances in which government forces took over schools. Deliberate attacks on schools and other civilian structures not being used for military purposes are war crimes. Attacks on schools by Boko Haram, displacement as a result of attacks on villages, and the use of schools by Nigerian army soldiers not only damage schools but interfere with access to education for thousands of children in the northeast.

According to Human Rights Watch research, Nigerian security forces failed to take all feasible precautions to protect the civilian population in their military operations against Boko Haram.

In December, Nigerian security forces attacked and burned down the village of Mundu near a Boko Haram base in Bauchi State, witnesses told Human Rights Watch, leaving 5 civilians dead and 70 families homeless. Villagers told Human Rights Watch that Boko Haram was not present in the village when it was attacked.

“The soldiers were shouting in what sounded like English, which most of us did not understand,” the village leader told Human Rights Watch. “We all began running when the soldiers started shooting and setting fire to our homes and other buildings. We returned two days later to find five bodies.” The dead included an 80-year-old blind man burned in his home, a homeless woman with mental disabilities, two visitors attending a wedding in the village, and a 20-year-old man, all of whom were shot.

Army authorities in Abuja said they were unaware of the incident when presented with Human Rights Watch’s findings on March 11, but said they had ordered military police to investigate the claims.

According to media reports, between September and March, Nigerian military authorities charged and tried 307 soldiers who had been on operations in the north for “cowardice,” mutiny, and other military offenses, sentencing 70 of them to death. Human Rights Watch opposes the death penalty in all circumstances because of its inherent cruelty. No military personnel have faced prosecution for human rights abuses against civilians in the northeast.

“Civilians in the northeast desperately need protection from Boko Haram attacks and they should never be targeted by the very soldiers who are supposed to be defending them,” Segun said. “The military’s decision to investigate the alleged violations in Mundu is an important first step toward ensuring accountability and compensation for the victims.”

In January, the African Union (AU) endorsed a multinational task force comprising of troops from Nigeria, Chad, Cameroon, and Niger to fight Boko Haram after the insurgents increased cross border attacks into Cameroon, Niger, and Chad. The action followed attacks on numerous villages and towns in northeastern Nigeria.

The AU is seeking a United Nations Security Council resolution to endorse the task force. Since early March, Nigerian security forces aided by forces from Cameroon, Chad, and Niger have dislodged Boko Haram from some areas of Nigeria’s northeast.

The situation in Nigeria is under preliminary examination by the International Criminal Court (ICC) prosecutor. Preliminary examination may or may not lead to the opening of an ICC investigation. The Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court on February 2, 2015, warned that persons inciting or engaging in acts of violence in Nigeria within the ICC’s jurisdiction are liable to prosecution by Nigerian Courts or the ICC. The ICC is a court of last resort, which intervenes only when national courts are unable or unwilling to investigate and prosecute serious crimes violating international law.

Nigerian authorities should ensure that the December 6 attack on Mundu is effectively investigated and that any military personnel, including commanders, responsible for human rights abuses and war crimes are held to account. War crimes by Boko Haram should be properly investigated and the perpetrators held to account in fair trials, Human Rights Watch said.

“The increased military effort has not made the situation for civilians in northeastern Nigeria any less desperate,” Segun said. “Without a stronger effort to protect civilians and accountability for abuses, the situation can only get worse.”

Background

In late January, Human Rights Watch interviewed 26 internally displaced persons (IDPs) aged between 14 to 58, and 13 others including journalists, aid workers, and government officials in Bauchi, Jos, and Karu, in northeastern and north central Nigeria.

According to a March 2015 report by the International Organization for Migration, more than 92 percent of people displaced by the conflict are staying with family members or other host families in communities where they have little access to humanitarian support, stretching the already limited capabilities of host families. Representatives of international non-governmental agencies told Human Rights Watch that lack of access to internally displaced people and inadequate funds hamper their efforts to provide relief and protection to those groups.

Specific incidents and patterns of abuse are described below.

Nigerian Army Attack in Mundu, Bauchi State

On December 6, 2014, Nigerian army soldiers attacked the village of Mundu, in Bauchi State, leaving at least five civilians dead and burning down most of the village, according to witnesses interviewed separately by Human Rights Watch. Six months earlier, the village leader had told the army that “strange people” whom he believed were members of Boko Haram had set up a camp in the forest 2 kilometers away. Soldiers visited the village in June and August asking for details of the camp’s location, which residents could not provide since they were afraid to go into the forest.

Mundu residents interviewed by Human Rights Watch said the village did not have Boko Haram members and that Boko Haram did not have fighters stationed there including at the time of the attack. The witnesses said that on occasion Boko Haram members came to the village market to buy food and other supplies, warned residents not to report their presence to the security forces and then returned to the nearby forest.

As the attack began, a low-flying helicopter hovered over the village, another village community leader said. Then hundreds of soldiers in 7 armored personnel carriers and 30 military trucks entered the village, and the soldiers opened fire, he said.

Satellite imagery recorded on December 14 and 24 and analyzed by Human Rights Watch provides compelling evidence of extensive fire burn scars across the village, and shows that at least 490 out of 550 structures were most likely destroyed by fire. The distinctive burn scar pattern surrounding village housing, separated by healthy vegetation and unaffected topsoil, is consistent with an arson attack, Human Rights Watch said.

When presented with the findings in a meeting on March 11 in Abuja, army authorities said they were unaware of the incident. The leader of the team of military investigators said that the chief of army staff, Lt. Gen. Kenneth Minimah, had ordered “the immediate deployment of the military police to investigate the allegations.”

Deliberate attacks on civilians and property, as well as attacks that do not discriminate between civilians and combatants are prohibited under international humanitarian law, which is binding on all parties to the conflict. Summary executions violate both the laws of war and international human rights law.

Boko Haram Attacks in Gwoza Area, Borno State

On August 6, 2014, Boko Haram fighters attacked and seized control of the Gwoza local government area, in Borno State. Witnesses told Human Rights Watch that many of the male residents of the town and surrounding villages fled to the Gwoza hills where, from a rocky lookout, they watched as the insurgents mounted their black flag over the local government headquarters, corralled 300 hundred of the town’s women and children into vehicles and drove them toward Sambisa Forest, where Boko Haram has a camp.

The insurgents also rounded up hundreds of men and boys over age 10. Those who refused to join Boko Haram were shot or slaughtered with machetes, witnesses said.

One 45-year-old man said: “I saw two of my nephews ages 13 and 18 slump down and die as the insurgents rained blows on them with guns and machetes.”

After five months during which other residents remained trapped on the hills, hiding in caves and weakened by hunger, Boko Haram attacked the civilians there, killing many and forcing others to escape over the border into Cameroon.

A 55-year-old man from Gwoza with a physical disability from childhood polio said he and his family fled to the hills after the August 6 attack fearing he would be killed because he wouldn’t be useful to the Boko Haram forces who he referred to as “insurgents”:

For about a week after we fled, we would sneak back home to eat meals prepared by women left in the town. By the second week, seven out of nine young men who sneaked into the town to eat were shot and killed by insurgents, who had now fully taken control of the town. For another seven weeks we survived on what little food young children could sneak to us up on the hill. Hunger was a constant problem. Women, including my stepmother and sister-in-law who tried to help us were abducted and taken away by the insurgents.

By August the insurgents began to come up the hills to kill many people so we left for Cameroon with about 70 others until transporters paid by the Borno State government brought us back to Yola. It was from there that I found my way to Jos.

Boko Haram Attack in Michika, Adamawa State

In Michika, a commercial town near the Cameroon border in northern Adamawa State, at least 30 people were killed, news media reported, when Boko Haram sacked the town in September 2104.

A 46-year-old woman who witnessed the Michika attack told Human Rights Watch that Boko Haram fighters killed many of the men, sparing only the people with disabilities and the elderly and took away young women and girls to a nearby forest. “When I went back home the following day, there was no trace of my missing husband and four children,” the woman said. “Muslim leaders helped to bury the bodies of 10 of my relatives.”

A 35-year-old Christian woman from Michika, Adamawa State, said on the day of the attack, a Sunday, she was attending a church service when a Muslim neighbor who was a member of a local defense group rode up on a motorcycle and warned everyone to leave because the town was being attacked:

He advised us not to run to a nearby wooded area because the insurgents had laid an ambush. We began to hear the gunshots and panic ensued. My husband insisted that I should run with our three children while he hurried home to get food and money. We later met up in another village, and then trekked from place to place for over one month before we got a commercial bus to Yola. We left Yola for Jos after Mubi fell because of the fear of an imminent attack on Yola.

My father and father-in-law were too old to run with us so both were left behind in Michika. I later heard that from neighbors who escaped that my father was killed by Boko Haram when he fled to Kwapala. We still do not know the whereabouts of my 85-year-old father-in-law.

Boko Haram Attack in Yelwa, Bauchi State

Residents of Yelwa, in the Darazo local government area, fled in July 2014 after over 100 armed men surrounded the mosque where male villagers were praying during the holy month of Ramadan, according to witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch. The men informed the worshippers that they were Boko Haram and that for the next nine months their group would occupy the nearby wooded area called Kukabiu. A 29-year-old woman from Yelwa said that when the armed men arrived in early June, they warned villagers not to allow their children to go to school:

They warned us that no one should teach, but because I am educated with a diploma in legal studies I want my children to also go to school. The strangers came back repeatedly to beat and harass our vigilante men [who were trying to protect the village]. Then one day, they burned down all the schools in our community. When dozens of soldiers and vigilantes failed twice to push the insurgents out of the nearby Kukabiu forest, we knew we were no longer safe. Everyone in the village fled out of fear that the insurgents would retaliate against us for reporting them to the military. I and thirteen members of my family are now squatting in this one room. I have qualifications to work but there are no jobs for us here.

Forced Recruitment by Boko Haram

A 30-year-old woman from Potiskum in Yobe State, told Human Rights Watch she and her family of eight were forced to flee to Bauchi in July 2014 because Boko Haram was killing people in the area, forcibly recruiting young men and kidnapping women:

We left Potiskum in July 2014 when we realized that there was no protection from Boko Haram. When they attack, everyone will run away, including soldiers and vigilante members. Those who did not run were forced to join the group. The new recruits would later return to take their wives and children by force to the Boko Haram camp and they were never seen again. I became afraid because my daughter was engaged to be married to a young man. What if he joined Boko Haram and takes her with him? So we fled with her to Bauchi. We don’t know what has become of her fiancé.

A 24-year-old man from the village of Damaturu in Yobe State said:

I began to notice changes in some of my friends who I grew up with in Damaturu. Initially we heard preaching about jihad, but those doing it hid the fact that they had joined Boko Haram. They targeted men and boys between 16 and 30. I panicked when I saw that my friends who yielded to the pressure would not only move to the insurgents’ nearby camp, but also take their wives and children with them.

I became confused and afraid but I did not want to join because of the bad things they were doing. I don’t think they truly fear God. The new recruits were forced to extort, steal, kidnap, and rape women and girls. When they threatened to kill me if I did not accept to join, my mother got some money to transport me and three of my younger brothers who were also being pressured by the insurgents. We left Damaturu to stay with our uncle in another state that night and have not returned home.

A 14-year-old boy from Yelwa, Bauchi State, described what happened when Boko Haram came to his village in June 2014:

I was afraid when Boko Haram came to the mosque in my village to preach during the fasting period. There were children around my age and younger with them carrying guns. The young fighters joined them to burn down the primary school where I was a student. When they began to harass our village emir to volunteer 10 young men to join their group, we all abandoned the village. No one stayed back, not even the emir. We are scattered in different places but most of us are in Bauchi. I want to return to school, but have not had the opportunity.

Attacks on Schools by Boko Haram

Boko Haram, whose name means “Western education is forbidden,” has attacked schools and abducted students and teachers from schools since early 2012.

Displaced people told Human Rights Watch that they had seen child fighters during Boko Haram attacks on their communities in Borno State, and that Boko Haram had burned school buildings. As a result of the attacks on schools and the killing of students and teachers, Borno State authorities had closed down schools in March 2014 without providing alternatives. The army later used a number of schools that were still standing as military bases, resulting in further attacks on the schools by Boko Haram.

Many displaced people expressed concern that their children were unable to go to school in camps for displaced people and host communities. The attacks on schools and the limited educational opportunities for displaced children have further impeded access to education for already disadvantaged school-age children in the northeast. According to the most recent National Education Data Survey, in 2010 children in northeast already made up more than 60 percent of Nigeria’s estimated 10.5 million children who are not in school.

A 36-year-old teacher who fled the village of Waga Mongoro village, near Madagali, Adamawa State, said Boko Haram attacked his village on May 12, 2014, and burned down the school where he taught:

They came from the direction of Limankara, Borno State, where they killed many people, and kidnapped the pregnant wife and two children of my friend, a pastor. Once we heard that the insurgents had blown up the bridge linking Adawama with Borno State, the men of Waga fled to the hills. We only returned during the day to work and to eat. When in August Boko Haram attacked Limankara again, sacking the Mobile Police training academy, fear began to rule our lives.

The military tried to stop the insurgents from coming into Adamawa State but we were shocked to see them driving back with full speed on the armored personnel carriers two days later, shooting in the air. We took this as signal to escape and fled to a primary school in Tur, near the Nigeria/Cameroon border. Again Boko Haram fighters attacked Tur and burned down the school so we fled to Ville.

Unfortunately, the insurgents seemed to be on our trail as they struck Ville, burning down schools and other buildings. My family scattered in different directions…. In early January 2015, my wife and other three children who were stuck elsewhere were able to join me in Jos. We have been here for about one month now and my children are missing out on their education. I am concerned as a father and a teacher that I am unable to help them. I can only hope that their future would not be wasted.

Nigerian Military Use of Schools

Nine witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that soldiers took over closed schools in the Borno communities of Chinene, Ngoshe, Ashigashiya, Wuje, Pulka, and Gwoza, among others.

In some locations, including Gwoza, the use of school buildings as military bases appears to have led to Boko Haram attacks on the schools.

A 42-year-old man displaced from Khalawa village in Gwoza, Borno State, said:

Soldiers were using the primary school in Chinene, Wuje primary school at Pulka junction for about three months, and the government secondary school in Ngoshe, all in Gwoza, as military bases. They were stationed in Chinene for close to two months, from April to June 2014. I saw soldiers taking five men they arrested from Barawa and Dogode for being members of Boko Haram into Chinene primary school. They detained them there for some days before taking them away in a military vehicle.

The soldiers were later forced to evacuate the schools and the entire area when Nigeria Air Force jets were dropping bombs over the area. Many buildings including schools were destroyed during the air raids. Boko Haram fighters burned down the schools in Chinene and Ngoshe when they took over the towns in June.

Under international humanitarian law, schools are generally protected from attack as civilian objects. But the presence of troops and weapons in a school can make a school a valid target for attack. Even in schools that are not attacked, military use can damage or destroy school infrastructure and education materials can be lost.

The United Nations Security Council’s adopted Resolution 2143 (2014) encouraged all UN member states “to consider concrete measures to deter the use of schools by armed forces and armed non-State groups in contravention of applicable international law.” Children have the right to education under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights to which Nigeria is party.

Guidelines for Protecting Schools and Universities from Military Use during Armed Conflict offer guidance to parties to conflicts on how to avoid the military use of educational facilities for military purposes and to mitigate the impact the practice can have on students’ safety and education.

The Nigerian government should incorporate the provisions of the guidelines into domestic legislation, or into its military doctrine and policy, to help protect students in armed conflict. The Nigerian government should also take concerted steps to improve access to education for children in Nigeria, including for children displaced by conflict in the northeast.