Lagos — As I waited at Nigeria's Murtala Mohammed Airport in Lagos, watching bags of various colors and shapes tumble onto the carousel, I cast a glance around the airport. It always feels good to be back in the city that was my home for over 20 years. Nearby were four men I believed were airport officials from the ID cards on lanyards around their necks. They were talking animatedly.

One who appeared to be the leader of the group was seated on a high stool with the other three fanned out in front of him. They were talking about a story in a newspaper. Occasionally, one of them would jab his index finger at the offending news story. I moved a little bit closer and stole a glance at the newspaper. The topic? The current trial of Boko Haram suspects.

"They shouldn't even be tried, they should be shot," one of them said. "They were suicide bombers; they were planning to kill themselves in any case," the same man added for emphasis. "Why is government wasting money taking them to court?" another man asked. "These people [Boko Haram] are so wicked, they deserve their fate," a third man posited, without clarifying what their fate was, but I assumed it meant being convicted and possibly executed.

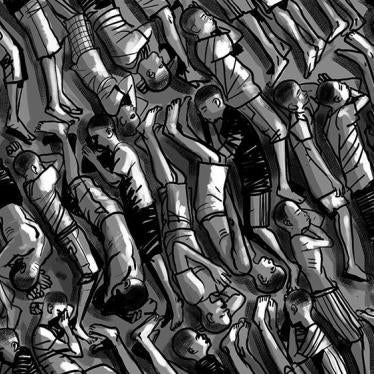

These suspects are facing mass trials at four civilian courts set up in a military base in Kainji, in central Niger state, where 1,669 suspects – 1,631 men, 11 women, 26 boys and 1 girl – have been held, some for several years, without charges or trial.

The military has arbitrarily arrested thousands of civilians without access to lawyers for alleged involvement in the Boko Haram insurgency. The conflict has killed at least 20,000 people since 2009, and pushed millions to overcrowded and poorly maintained camps for internally displaced people, where scores of girls and women have faced rape and sexual exploitation.

I was a journalist and activist during Nigeria's military dictatorship in the 1990s, during the dark days of the Ibrahim Babangida and Sani Abacha military dictatorships. They periodically hauled civilians and military officials before military tribunals for allegedly plotting to overthrow their governments, such trials often ending in the accused being executed on controversial evidence.

As I listened to the airport conversation, I started thinking: What if some of those being tried in Kainji have nothing to do with Boko Haram? What happened to constitutionally guaranteed fair trial standards, like the right to be heard by a competent, independent and impartial tribunal? The right to a public hearing? The right to be heard within a reasonable time ? What if these suspects were eventually found to be innocent after being held for several years? How about the fact that Nigeria is no longer under military dictatorship?

I casually moved toward the four men, attempting to join the conversation, but they all quickly shuffled away in different directions. Perhaps in their minds I could be a secret service agent sniffing around for information. For them and possibly many Nigerians, Boko Haram attacks have been too dastardly and the insurgents too brutal to raise questions about the suspects' rights; they should be punished, even if it is by means of a secret trial. After all, those convicted by a military tribunal for the 1976 assassination of Murtala Mohammed, the military head of state for whom the Lagos airport was named, were tried secretly. Nigeria has a long history of secret trials. I spotted my bag, picked it up, and stepped into the embrace of the Lagos sun.