In the 1980s and early 1990s, a large number of Afghans fled to the Netherlands to escape the dire situation in their own country. But they weren't the only ones who left.

Senior government officials, including agents of the secret service - the dreaded KhAD - who had engaged in human rights violations also landed on Dutch soil.

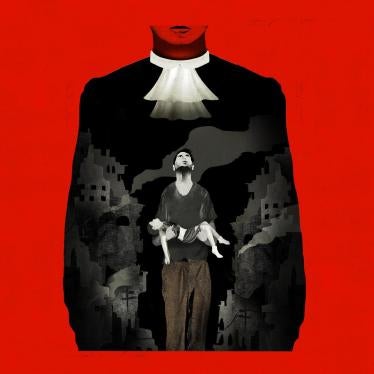

Imagine escaping torture in your home country for exile far away, then suddenly crossing paths with the person responsible for your suffering. Dutch media reported in 1997 that at least 35 Afghan war criminals had sought asylum in the country and were walking around freely - at times coming face-to-face with their victims.

The article caused a public outcry and led the Dutch government to create a special unit within its immigration service to identify people responsible for serious international crimes.

The "1F Unit," a reference to article 1F of the UN Refugee Convention, had a clear mandate: keep the Netherlands from becoming a safe haven for war criminals.

Most often, this meant denying people suspected of serious international crimes asylum and sending them home. But many couldn't be sent back under the international law principle of non-refoulement, which prohibits return if persons' lives would be threatened or they would face a real risk of torture or other serious mistreatment.

These people became "unwanted aliens," permitted to stay but with no legal status or rights.

In 2000, the Dutch government began authorising immigration officials to share these individuals' files with prosecutors.

Prosecutors used the information to pursue three senior Afghan intelligence officers, securing two convictions for torture and war crimes in Dutch courts in 2005. Prosecutors had a fourth Afghan suspect in their sights, but he died in 2013 shortly before he could be arrested.

The number of asylum seekers in the world is at its highest in nearly 70 years, with many coming from conflict zones like Syria where mass atrocities have been committed.

So it isn't that far-fetched to think that the situation faced by Afghan refugees in the Netherlands could happen elsewhere.

Last year, the United Kingdom reported that it had identified nearly 100 suspected war criminals living in the country. Also last year, a former political prisoner in Ethiopia who had seen many of his fellow detainees tortured and killed literally ran into the man responsible for the crimes in a restaurant in Denver.

There is a growing realisation that countries need to pay more attention to ensuring that they don't become safe havens for war criminals and that those responsible for the world's worst crimes are brought to justice.

Through a principle known as universal jurisdiction, more and more courts in countries faraway from where crimes were committed are stepping in to prosecute them. For that to happen, criminal justice authorities need to work together closely and they need the assistance of immigration authorities to identify potential suspects on their soil.

Giving police and prosecutors access to immigration files does raise concerns.

One of the Afghans convicted by Dutch courts filed a challenge with the European Court of Human Rights, saying the practice violates his right against self-incrimination.

The French agency responsible for processing asylum applications has also resisted sharing information with prosecutors on the grounds that it risks compromising the integrity of the asylum process.

There is a need for safeguards in how and what information can be shared, and information shouldn't be shared until after immigration authorities have decided whether a person is entitled to refugee status.

People should be told at the outset that information provided during the asylum process may later be shared with police and prosecutors, and they should be given legal assistance during questioning about these crimes.

Only information relevant to the crimes should be given to police or prosecutors, and it should only be used as investigative leads and not as actual evidence in criminal trials.

The Netherlands has taken the lead in trying to meet its responsibilities toward refugees and at the same time deal with the kinds of crimes that cannot be forgotten.

Other countries in the European Union should follow its lead to ensure that those responsible for atrocities don't escape justice.

Leslie Haskell is international justice counsel at Human Rights Watch.