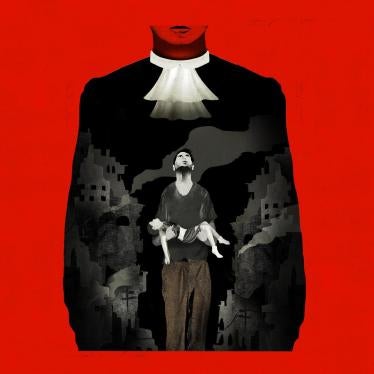

(Tunis) – The trial before the Le Kef military Tribunalof former President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali and others underscores the steps that must be taken if Tunisia’s judiciary is to hold officials of the ousted regime fully and fairly accountable for human rights violations. Human Rights Watch observed the trial for killing protesters during Tunisia’s 2010-2011 uprising, which concluded on June 13, 2012, and studied parts of the 1,066-page written verdict.

The assessment of the case – and the related cases of 22 other former high-ranking Tunisian officials – identifies positive aspects of the proceedings but concludes that legal flaws left the tribunal ill-equipped to identify those who carried out the killings and to address the culpability of high-ranking officials. It further emphasizes that such cases should in the future be heard before a civilian rather than a military court. It says that while international law does not strictly prohibit trials in absentia, Ben Ali, who was sentenced to life in prison, is entitled to a new trial if he returns to Tunisia.

“The trial of Ben Ali and other top officials is an important step toward the rule of law for Tunisia, but the verdict will remain toothless unless Ben Ali is returned to Tunisia and can answer his accusers face to face,” said Eric Goldstein, deputy Middle East and North Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “The Tunisian government should also revise its domestic law in order to reduce the overly broad jurisdiction of military tribunals on possible human rights violations committed by military and security forces.”

Ben Ali fled to Saudi Arabia on January 14, 2011, and, though an international arrest warrant is pending against him, the Tunisian government has made only perfunctory efforts to get Saudi Arabia to extradite him for trial. On February 17, on the eve of an official visit to Saudi Arabia, Hamadi Jebadi, the new head of government, said on Radio Sawa that he did not plan to raise Ben Ali’s extradition with his hosts, calling the case “minor, not a priority.”

The trial of Ben Ali and other high-ranking officials was held before the Le Kef Permanent Military Tribunal, one of three military tribunals in Tunisia. The tribunal addressed killings in the governorates of Le Kef, Jendouba, Béja, Siliana, Kasserine, and Kairouan in December 2010 and January 2011. The security force reaction was most violent in the central western cities of Kasserine and Tala, where 23 people died and hundreds were injured. A second multi-defendant trial, in which Ben Ali is again one of several former high-ranking officials on trial, is ongoing before the Tunis Permanent Military Tribunal.

The Le Kef Permanent Military Tribunal sentenced Ben Ali to life in prison for complicity in murder under article 32 of the penal code. It handed down a 12-year sentence on the same charge to Rafiq Haj Kacem, interior minister from November 2004 to January 12, 2011; and 10 years each to Adel Tiouiri, former director general of National Security; Jalel Boudrigua, former director of the Anti-Riot Police (Brigades de l’ordre public, BOP); Lotfi Ben Zouaoui, former director general of Public Security; Youssef Ben Abdelaziz, former brigadier general in the Anti-Riot Police; and Khaled Ben Said, former director of Special Anti-Terrorist Brigades. The tribunal also sentenced six lower-level officers to prison sentences ranging from 1 to 15 years for the murder of protesters under articles 201, 202, and 205 of the penal code.

The tribunal acquitted several other defendants, among them Ali Seriati, director general of the Presidential Guard from September 1, 2001 to January 14, 2011, and Ahmed Friâa, interior minister between January 12 and 27, 2011. It acquitted several commanders supervising the security forces in Tala and Kasserine during attacks on protesters, including Moncef Laâjimi, head of the Anti-Riot Police in Tala from January 10 to 12, and Moncef Krifaâ, regional director of the Anti-Riot Police at the time of the events, as well as several other lower-level officers.

In its assessment of the 1,066-page written verdict of the Le Kef Permanent Military Tribunal (see below), Human Rights Watch recounts the procedures, testimony, and evidence introduced by all the parties to the trial, and explains the court’s reasoning in convicting some defendants and acquitting others.

The trial in the Le Kef Permanent Military Tribunal began on November 28, 2011, after civilian investigative judges from Kasserine, Le Kef, and Kairouan courts transferred the cases to the military justice system based on Law 70 of August 1982 regulating the Basic Statusof Internal Security Forces. That law assigns to military courts cases involving agents of the internal security forces for their conduct during the exercise of their duty.A crystallizing norm of international law, though, requires that civilian courts should have jurisdiction over all cases of human rights violations involving civilians, regardless of whether the defendants are civilian or military. Tunisian authorities should reform domestic law to restrict military jurisdiction to purely military offenses, Human Rights Watch said.

The tribunal held 10 hearings, during which it interrogated the accused, heard the testimony of several witnesses, and examined requests for further evidence from the defense and victims’ lawyers. Oral arguments started on May 21. After the verdict, the public prosecutor and defense lawyers announced that they will appeal to the military appeals court, created by decree-law 69 of July 29, 2011.

The military tribunal faced a number of challenges in trying this case, Human Rights Watch concluded. The military investigative judge was able to identify the specific security personnel who killed the protesters in only three of the 23 Kasserine and Tala cases. And he was unable to find concrete evidence that superiors had ordered lower-level security personnel to use deadly force to quell protests. In the absence of strong material evidence and testimony by witnesses, the prosecutor and the judges relied on inferential reasoning to convict some of the accused commanders.

Tunisia’s penal code is ill-equipped to handle such cases, Human Rights Watch said. It does not address the concept of command responsibility, which is recognized under international law and makes commanders and civilian superiors liable for crimes committed by their subordinates if the superiors knew, or had reason to know, of the crimes and failed to prevent or punish them. Under Tunisian law, the prosecutor would generally have to show actual knowledge of the crime and orders to commit it to prove complicity. Tunisia should integrate the concept of command responsibility into domestic legislation, Human Rights Watch said.

“This verdict against Ben Ali and his security chiefs sends a strong warning to high officials that they need to exercise due diligence in preventing serious crimes and violations of human rights,” Goldstein said. “But the Tunisian government should move quickly both to have Ben Ali repatriated and retried and to implement the legal reforms necessary if future trials are to meet international standards.”

The Trials for Killing Protesters

A second case against former Tunisian President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali Ben Ali was also concluded on June 13. In that trial, the Permanent Military Tribunal of Tunis sentenced Ben Ali in absentia to 20 years in prison for incitement to use arms and provoke sedition under article 72 of the penal code. The case concerned the killing of six people when police opened fire on members of neighborhood defense committees on January 15, 2011, in Ouardanine, a town 120 kilometers south of Tunis.

In an earlier case relating to killings during the uprising, on April 30, the Permanent Military Tribunal of Sfax sentenced two policemen, Omran Abdelali and Mohamed Said Khlouda, to 20 years in prison and an 80,000 dinar fine (US$49,230). The policemen were found guilty of killing Slim Hadhri, who was shot dead while participating in a demonstration on January 14, 2011, in Sfax, a city 270 kilometers south of Tunis.

A second multi-defendant trial continues at the Tunis Permanent Military Tribunal, where 42 people are accused of killing 43 protesters in the governorates of Tunis, Ariana, al-Manouba, Ben Arous, Bizerte, Nabeul, Zaghouan, Sousse, and Monastir. As in the Le Kef Trial, defendants in the Tunis trial include Ben Ali, his two former interior ministers, and the former directors general of the security forces. The others charged in the Tunis trial are Mohamed el Arbi Krimi, director of the Central Operations Room at the Interior Ministry; Ali Ben Mansour, the inspector general of security forces; and Rachid Ben Abid, the director of Special Services, as well as a number of other high commanders and lower-ranking officers.

Due Process, Transparency, and the Independence of the Court

The Le Kef Permanent Military Tribunal appears to have respected certain basic rights of the defendants. The defendants had the right to a lawyer of their own choosing and had ample opportunity to present exonerating evidence and to call witnesses to testify. Journalists could attend the proceedings and extensively covered the views of victims and defense lawyers in print, radio, and television media.

The reform of Tunisia’s code of military justice in July 2011 introduced several improvements to the military justice system by allowing victims to file complaints, make claims for reparation, and be represented before the military courts. The reform also created an appeals court, which can retry the case both on the law and the facts.

However, the defense minister is the head of the High Council of Military Judges, which oversees the appointment, advancement, discipline, and dismissal of military judges, creating concerns about the independence of the military courts.

Tunisian authorities should reform domestic law to restrict the jurisdiction of military courts to purely military offenses, Human Rights Watch said. Under Tunisian law, the jurisdiction of military courts is extended to also cover crimes committed by security forces. Article 22 of Law 70 of August 1982 regulating the Basic Status of Internal Security Forces grants military tribunals jurisdiction over all crimes alleged to have been committed by members of the security forces, regardless of who the victims are or the capacity in which the crimes were allegedly committed.

This broad jurisdiction contravenes a basic norm of international law, which requires trying human rights abuses in civil courts. A growing body of jurisprudence from the human rights monitoring bodies urges countries to try military personnel who are charged with human rights violations in civilian courts. In Suleiman v. Sudan, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights affirmed that military tribunals should only “determine offences of a purely military nature committed by military staff” and “should not deal with offences which are under the purview of ordinary courts.” In addition, the principles and guidelines on the right to a fair trial and legal assistance in Africa proclaimed by the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights states, “the only purpose of Military Courts shall be to determine offences of a purely military nature committed by military personnel.”

Trying a defendant in absentia, although not prohibited, is strongly disfavored by international law. The tribunal in charge of the trial should institute procedural safeguards to ensure the defendant’s basic rights, such as the notification of the defendant in advance of the proceedings, his right to representation in his or her absence, and a fresh determination on the merits of the conviction following the person’s return to the jurisdiction.

Tunisian criminal procedure law does not have specific provisions on trials in absentia. The Le Kef Tribunal did appoint a lawyer to defend Ben Ali, but the lawyer did not participate fully in the proceedings. During the final pleadings, he was present but declined to make an argument. These elements indicate that the minimum procedural safeguards for trials in absentia were not met in this case.

Basis for Conviction

The indictment largely consists of interviews by the military investigative judge of hundreds of witnesses but few witnesses were able to identify the killers in specific cases. They recount the events and describe the manner and the circumstances of the use of lethal force by the police but do not identify the people who fired the fatal shots, likely in part because the police forces operating in Tala and Kasserine at the times of the events consisted of a mixed group of local agents and agents from other regions providing back-up. In addition, the case file does not contain detailed ballistic information. At the time the civilian investigative judge started the investigation, in February 2011, most of the bodies had already been buried without proper forensic examination. Authorities exhumed six bodies, but these revealed little probative evidence.

The investigative judge only charged three people with actually firing fatal shots. Those three were: Bechir Bettibi, an Anti-Riot police officer charged with killing Wajdi Saihi in Tala on January 12, 2011; Mohamed Mujahed Benhoula, an Anti-Riot police officer accused of killing Mohamed Amine Mbarki in Kasserine on January 8; and Wissam El Ouartatani, the police chief in Kasserine accused of killing Abdel Basset Kassemi on January 8.

All three were convicted based on the testimony of witnesses and of fellow officers. The judges concluded that in most situations in Tala and Kasserine police had fired on people who were not engaged in violence. They convicted two of the officers of murder without premeditation under article 205 of the penal code and the third with premeditated murder under article 201 of the penal code. They considered that the officers’ actions did not meet the conditions for the use of firearms imposed by Law No. 4 of 1969 on public meetings, processions, parades, public gatherings, and assemblies.

The judges found some of the security chiefs guilty while acquitting others based on their degree of control over the units on the ground and whether they were directly involved in organizing the security forces to quell the protests.

The investigative judge could not find conclusive evidence that commanders had ordered police officers or other security personnel to use deadly force to repress the protests. In response to questioning by the judge, the indicted police officers denied having received orders to use live ammunition. The investigative judge also failed to find any recorded orders at the central operations room of the Interior Ministry, where all telephone conversations to and from the unit’s landlines are recorded on a hard drive.

The defense lawyers for the three directors general of security forces contended that the prosecutor’s failure to prove the existence of orders to use deadly force should result in their acquittal since the crime of complicity in murder, for which they were charged, requires, under Tunisian law, proof of an actual act by the accused to assist the murder.

In addition, some of the defendants tried to show that they had exercised due diligence in handling the situation. For example, Tiouiri, the former director general of national security, introduced evidence that he had given orders at 10 a.m. on January 9 to all police stations to exercise restraint when facing the protesters and to avoid using live ammunition. He also claimed that after the deadliest incidents on January 8 and 9 in Tala and Kasserine, he ordered the security commanders in the two cities replaced with other commanders.

In the written verdict, judges relied on inferential reasoning and circumstantial evidence to justify the conviction of the directors of security forces. They surmised the existence of orders to use deadly force from the two speeches of Ben Ali, the first on January 10 in which he vowed to quell protests firmly and the second on January 13, the eve of his departure, when he said, “Stop using live ammunition,” a sentence the judges interpreted as implying the existence of previous orders to use live ammunition.

The judges also inferred that all the directors general of security forces were part of this plan, because they participated in the crisis meetings on January 9, 10, 11, and 12 to devise a strategy for facing the protests. They assumed that orders to use force to quell protesters were given by the highest echelons of the state through the directors general of security forces, to the regional directors of anti-riot police in Tala and Kasserine, who then transmitted the orders to lower-ranking officers. The failure to identify the people who fired the shots in 20 of the 23 killings in Kasserine and Tala curtailed the ability of the tribunal to determine the truth of what happened and individual responsibility for the killings.

Basis for Some Acquittals

Eight defendants were acquitted and the written judgment summarizes the exonerating evidence. For example, Seriati, former director of the Presidential Guard, was acquitted of complicity in premeditated murder because the forces under his command did not participate in the repression of protesters and he was not involved in the decision-making process at the Interior Ministry. Likewise, Friâa was acquitted because he was appointed interior minister only on the afternoon of January 12, after the killings in Tala and Kasserine. Upon taking up the position, Friâa asked his director of cabinet to issue a ministerial order to use maximum restraint when facing protesters and avoid the use of live ammunition.

Laâjimi was acquitted of premeditated murder. He became director of the Anti-Riot Police in Tala only on January 10, 2011, replacing another commander after five people had been killed and several others injured in the city on January 8. The judges reviewed the charges against him and found that he had supervised the Anti-Riot Police there for only two days before his supervisor, Boudrigua, ordered him to withdraw from the city with his forces on January 12. On January 10 and 11, no one was killed in Tala, and on January 12 there was only one killing. In addition, the judges reviewed testimony from several of Laâjimi’s subordinates confirming that he had asked them to gather all the rifles from Anti-Riot Police officers and lock them in a secure place. In January 2012, Laâjimi was appointed deputy chief of cabinet in the Interior Ministry.

Verdict of the Le Kef Permanent Military Tribunal

Convicted:

- Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, former president, sentenced to life in prison for complicity in murder under article 32 of the penal code.

- Rafiq Haj Kacem, former interior minister, 12 years for complicity in murder under article 32.

- Adel Tiouiri, former director general of National Security, 10 years for complicity in murder under article 32.

- Jalel Boudrigua, former director general of the Anti-Riot Police, 10 years for complicity in murder under article 32.

- Lotfi Ben Ali Zouaoui, former director general of Public Security, 10 years for complicity in murder under article 32.

- Youssef Ben Abdelaziz, former brigadier general in the Anti-Riot Police, 10 years for premeditated murder under article 201 of the penal code.

- Wissam Ben Taha El Ouartatani, former Chief of Police in Kasserine, 15 years for premeditated murder under article 201.

- Bechir Bettibi, lieutenant colonel in the Anti-Riot Police, eight years for murder under article 205 of the penal code.

- Aymen Ben Abbas al Kouki, one year for manslaughter under article 217 of the penal code.

- Mohamed Benhoula, captain in the Anti-Riot Police, 10 years for murder under article 205.

- Khaled Ben Saîd, former director of the Anti-Terrorist Brigades, 10 years for murder under article 201.

- Dhahbi Abdi, 10 months for murder under article 201.

Acquitted:

- Ahmed Friâa, interior minister from January 12-27, 2011.

- Ali Seriati, former director general of the Presidential Guard.

- Moncef Laajimi, head of the Anti-Riot Police in Tala from January 10-12, 2011.

- Moncef Krifaâ, regional director of the Anti-Riot Police.

- Nomaan Ben Mohamed El Ayeb, major in the Anti-Riot Police.

- Ayech Ben Sousia, captain in the Anti-Riot Police.

- Khaled Ben Hedi El Marzouki, major in the Anti-Riot Police.

- Wael Ben Ali El Mallouli, first lieutenant in the Anti-Riot Police.

- Hssine Zitoun, former chief of Kasserine Governorate police.