(New York) – The government of Bangladesh took no significant steps to investigate and prosecute torture in custody and extrajudicial killings during 2011 and showed an increasing intolerance for criticism, Human Rights Watch said in its World Report 2012.The government missed the chance to ensure trials that meet international standards for the country’s independence-era atrocities.

Although the number of Rapid Action Battalion (RAB) killings has dropped following domestic and international criticism, there was a sharp increase in enforced disappearances, leading to concerns that security agencies have replaced one form of abuse with another. The government violated the right to a fair trial when it staged mass trials for thousands being held for the 2009 massacre of army officers by troops in the Bangladesh Rifles (BDR). Human rights organizations, journalists, trade unions, and civil society activists remained at risk, with some suffering attacks.

“The government of Sheikh Hasina has made repeated promises to end abuses and ensure justice and accountability, yet the security forces remain above the law,” said Brad Adams, Asia director at Human Rights Watch. “In the past year the government has moved from saying it would take action against abusive forces to denying abuses or defending the actions of the same abusive security forces that it complained about when it was in opposition.”

In the 676-page World Report 2012, Human Rights Watch assessed progress on human rights during the past year in more than 90 countries, including popular uprisings in the Arab world that few would have imagined. Given the violent forces resisting the “Arab Spring,” the international community has an important role to play in assisting the birth of rights-respecting democracies in the region, Human Rights Watch said in the Report.

In Bangladesh, the parliament took long overdue action in November to provide for returning property seized from the minority Hindu community. The action amended a 1965 law, passed when Bangladesh was still part of Pakistan, which allowed the appropriation of property of Hindus, who were suspected of supporting enemy India. Human Rights Watch cautioned, however, that the government should ensure that the new law is not used to target its political enemies. Belatedly, the government also took the positive step in bilateral meetings of protesting the killing of hundreds of Bangladeshi nationals by India’s Border Security Force over the past 10 years.

The Awami League government has taken steps to promote women’s rights, making commendable progress in reducing infant and maternal mortality rates. It introduced a policy to advance women’s rights in 2011, which among other things guarantees women an equal share and opportunity in employment and full control over their earnings. The government has also committed to developing a national strategy for social security, a positive step that could help reduce the high poverty levels among female-headed households.

However, the state continues its decades’ long discrimination against women under personal status laws and fails to take adequate measures to protect women and girls from violence. Violence against women is rampant, with religious leaders or village elders imposing illegal punishments under the garb of “fatwas.” These include orders to whip girls, blacken their faces, or otherwise humiliate them publicly for “immoral behavior.” In some cases, village elders illegally accused girls who reported rape or sexual abuse of having an affair and ordered them punished. The Bangladesh high court division ordered the government to take action against such extrajudicial punishments, but the government did not carry out court orders. The parliament passed a law in 2010 against domestic violence but has yet to introduce any rules for its implementation.

“The government has taken some important steps on women’s rights,” said Adams. “But too often it makes announcements and nothing changes for women on the ground.” Despite pledges, the government took no action against RAB personnel for human rights violations. In fact, the government has refused to acknowledge violations and prosecute those responsible despite criticism from the National Human Rights Commission, the findings of independent Home Ministry investigations, and lengthy reports from Human Rights Watch.

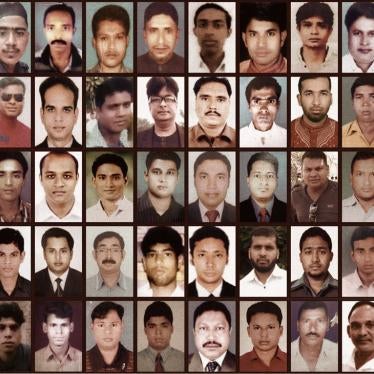

Bangladeshi human rights groups have documented nearly 1,600 extrajudicial killings since 2004. Many were disguised by law enforcement institutions as “crossfire killings.” The main unit responsible is the RAB, although that same culture of violations and impunity is infecting other security forces as members rotate back to their parent units in the police or intelligence departments, Human Rights Watch said.

“Despite clear and voluminous evidence of Rapid Action Battalion responsibility, the government has not held anyone in RAB accountable for the large numbers of extrajudicial killings,” Adams said. “While the government talks proudly of its democratic credentials, it seems to forget that a key component of a democracy is ensuring the safety of its citizens from state sponsored violence.”

Attempts by civil society during the year to document or denounce human rights violations at times resulted in harassment or torture, Human Rights Watch said. Odhikar, a Dhaka-based human rights organization, has come under increased surveillance and its employees have been harassed. The Asian Human Rights Commission said that its representative, William Gomez, was abducted by plainclothes security personnel in May and tortured and verbally abused during an interrogation. Supporters of high profile figures such as the Nobel Prize Laureate Mohammad Yunus were threatened and intimidated and, in one case, beaten up. Trade union leaders remained under severe pressure and at risk of arbitrary arrests. The nongovernmental organization bureau in the prime minister’s office held up grants to groups critical of the government.

“In 2011 the government appeared to hunker down and assume dark motives when human rights concerns were raised, demonizing critics instead of carefully considering their concerns,” Adams said. “In a democracy all points of view should be welcome and activities like human rights monitoring by domestic organizations should be encouraged, not disparaged.”

Many of the 6,000 members of the BDR charged for the 2009 mutiny which led to a massacre of dozens of army officers have faced serious fair trial violations, Human Rights Watch said. Of those charged, 850 face criminal charges under the Bangladesh penal code, which allows for capital punishment. Military courts convicted close to 1,000 in mass trials during 2011 without providing individualized evidence. Many accused did not have legal counsel or, if they did, lawyers did not have sufficient time or resources to provide an adequate defense.

Human Rights Watch and other groups have documented cases of severe abuse of BDR members during detention, particularly in the early aftermath of the mutiny. Many accused gave statements under duress, and others were compelled to provide testimony against other accused. International law proscribes the use of statements obtained under duress, and the use of these statements raises serious due process and fair trial concerns. The government has taken no steps to investigate these allegations or hold those responsible for abuse accountable.

Charges have been filed against seven people accused of war crimes during the 1971 war for independence. The first trial under the tribunal began in September against Delawar Hossein Sayedee. Some important amendments were made in June to the International Crimes Tribunal (ICT) Rules of Procedure, which included ensuring the right to a presumption of innocence, the right to a fair and public trial, the right against double jeopardy, and the right to counsel of the accused’s choice.

However, these amendments did not address other important shortcomings in the rules, such as the denial of interlocutory appeals, the need to establish a defense office, and the need to repeal article 47(A) of the constitution, which denies fundamental rights under the constitution to individuals accused under the ICT Act. The provision even bars claims that article 47(A) is unconstitutional.

The proceedings in Sayedee’s case raise serious concerns about the impartiality of the bench and the rights of the accused to a fair trial, Human Rights Watch said. The accused has been denied access to foreign counsel of his choice, and the defense teams contend that defense witnesses and investigators have been harassed.

“Bangladesh promised to meet international standards in these landmark trials, but it still has a long way to go to meet this commitment,” Adams said. “Bangladesh could have set the standard for other nations that have suffered from unspeakable abuses, but problems with the law and the conduct of the first trial are throwing away this opportunity.”