(New York) - States convening at the United Nations for a high-level meeting on Sudan on September 24, 2010, should press Sudanese authorities to ensure that the forthcoming referendum on southern independence is free of the human rights violations that marred the April elections, Human Rights Watch said today.

More than 30 nations and international organizations are expected to attend the meeting, convened by the UN secretary-general to coincide with the annual General Assembly meetings. Delegates are expected to express their support for the January 2011 referendum, which will determine whether Southern Sudan remains part of Sudan or secedes and becomes an independent nation.

"The delegates at the Sudan meeting should do more than confirm that the referendum will happen on time," said Rona Peligal, Africa director at Human Rights Watch. "This is also a prime opportunity for them to insist on better human rights conditions in Sudan."

The April elections and the upcoming referendum for southern independence are milestones in the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement, which ended 22 years of civil war in which an estimated 2 million people lost their lives.

Human Rights Watch remains concerned about impunity for human rights violations by security forces across Sudan, restrictions on civil and political rights, and the treatment of minority groups throughout Sudan. The two parties to the peace agreement - the ruling National Congress Party (NCP) and the southern ruling Sudan People's Liberation Movement (SPLM) - should state publicly that they will not expel each other's minorities in the event of secession, Human Rights Watch said.

The delegates to the September 24 UN meeting should also address the deteriorating situation in Darfur.

"Focus on the southern referendum should not shift attention away from the ongoing crises in Darfur," Peligal said. "The nations concerned about the situation in Sudan need to press Khartoum now to end impunity for ongoing human rights violations in Darfur."

Election-Related Violations

As Human Rights Watch has extensively documented, the national elections in April 2010 were deeply flawed. They were marred by human rights violations, including restrictions on free speech and assembly, particularly in northern Sudan. The elections also occasioned widespread intimidation, arbitrary arrests, and physical violence against election monitors and opponents of the ruling parties by Sudanese security forces across the country.

In the period following the elections, the human rights situation deteriorated further as the ruling party, using the National Intelligence and Security Services, cracked down on opponents, activists, and journalists in Khartoum and northern states. Human Rights Watch documented additional cases of arbitrary arrests of activists in August and September.

Human Rights Watch has repeatedly called on the Sudanese national government to enact key human rights reforms required under the peace agreement, such as reforming the repressive national security apparatus.

In Southern Sudan, election-related disputes sparked clashes between the southern government army, the SPLM, and aggrieved candidates and other opponents of the southern ruling party. In Jonglei state, for example, General George Athor, who unsuccessfully ran for governor, clashed with the southern army on multiple occasions. As of September, large numbers of the southern army's soldiers were still deployed in northern Jonglei state where civilians continue to report rape and other abuses. Soldiers have also conducted violent operations against armed groups aligned to opponents of the southern ruling party in Upper Nile state, resulting in human rights violations there.

Both national and Southern Sudanese authorities should hold their security forces accountable for human rights violations that occurred during and after the elections, Human Rights Watch said.

Civil and Political Rights Threatened

Although the head of the national security service in early August lifted pre-print censorship, other restrictions on political expression remain in place. During research in Sudan in August, Human Rights Watch found that both in the northern states, where authorities support the continued unity of Sudan, and in Southern Sudan, where authorities support southern secession, journalists and civil society are not free to speak openly about any opposition to the prevailing sentiment.

Human Rights Watch also found increased anxiety over the citizenship rights of southerners living in Khartoum and elsewhere in northern states. Southerners living throughout Sudan will be eligible to vote in the referendum. The vast majority of them live in Southern Sudan, but an estimated 1.5 million live in Khartoum and other northern towns, many in settlements for displaced persons.

In recent months, officials in the northern ruling party have publicly threatened that southerners may not be able to stay in the north in the event of a secession vote. Both southerners in the north and northerners living in Southern Sudan told Human Rights Watch that they feared retaliation, even expulsion, if secession were approved.

International standards protect people from arbitrary or discriminatory removal or deprivation of their nationality. The Sudanese authorities should publicly pledge that no one will be at risk of statelessness, or risk losing enjoyment of other basic rights, as a result of the outcome of the referendum.

"The UN meeting provides a perfect opportunity for the parties to declare there will be no expulsions of southerners from the north, or northerners from the south," Peligal said.

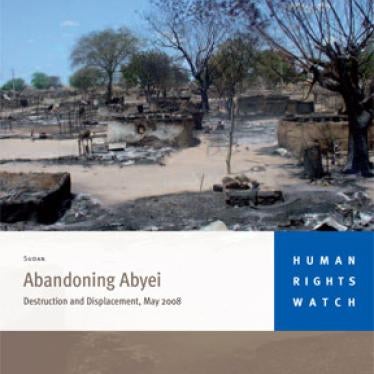

Impasse at Abyei

Delegates at the UN meeting this week should also press the two parties to the Comprehensive Peace Agreement to make it an urgent priority to resolve the political impasse over Abyei, the oil-rich area along the north-south border where northern and southern forces clashed in 2008. The issue remains a key flashpoint for further conflict and human rights abuses, Human Rights Watch said.

"The situation in Abyei could easily deteriorate and lead to more conflict without a concerted effort to protect civilians and defuse tensions on the ground," Peligal said.

Under the peace agreement, the area is to hold its own parallel referendum in January 2011 to decide whether it will belong to the north or south, but the parties have made no progress in agreeing on the arrangements for this vote or in taking steps to resolve differences between local populations and protect their rights, as Human Rights Watch documented in August.

The United Nations Mission in Sudan (UNMIS), which has a mandate to protect civilians, should increase its patrols throughout Abyei and other key volatile areas along the north-south border, and Sudanese authorities should ensure peacekeepers' access to these areas, Human Rights Watch said.

Abuses by Soldiers in Southern Sudan

The Sudanese government and international supporters should not ignore human rights violations by security forces in Southern Sudan, where election-related grievances have provoked human rights violations by the southern government's soldiers in the months following the April vote, Human Rights Watch said.

In northern Jonglei and Upper Nile states, for example, Human Rights Watch documented killings and rapes committed by these soldiers in June and July. The soldiers targeted civilians whom they accused of supporting "renegade" commanders and local militia groups who opposed the southern ruling party.

In Upper Nile state, the governing party's troops conducted particularly violent operations against a militia group allegedly linked to SPLM-DC, a breakaway political party led by Lam Akol. In one village, a 60-year-old woman told Human Rights Watch that soldiers had rounded up her son and three friends, tied their hands behind their backs, and shot them dead.

"These incidents underscore the urgent need for the southern government to instruct soldiers on their human rights obligations and to hold them accountable for all violations," Peligal said.

Human Rights Watch also urged human rights personnel for the UN mission to monitor and report on these abuses and to press the southern armed force to strengthen its accountability mechanisms before the referendum. International donors engaged in reforming the security sector in Southern Sudan should include accountability and human rights in their programs.

The Government of Southern Sudan has, appropriately, put the southern police forces in charge of referendum security, rather than soldiers who have been responsible for abuses, Human Rights Watch said.

Protect Civilians and Insist on Justice for Crimes in Darfur

Human Rights Watch also urged the international delegates to ensure stronger protection of civilians from ongoing violence and rights abuses in Darfur, Human Rights Watch said.

The delegates should insist that those wanted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide allegedly committed in Darfur appear in The Hague to face the charges against them. President Omar al-Bashir; Ahmed Haroun, the country's former minister for humanitarian affairs and current governor of Southern Kordofan state; and Ali Kosheib, a "Janjaweed" militia leader whose real name is Ali Mohammed Ali, are all subject to arrest warrants by the ICC.

The situation in Darfur has deteriorated in recent months, and the Sudanese government continues to carry out armed attacks on rebel factions and civilians.

In early September, for example, armed militias (some wearing military uniforms) on camels and horses and in vehicles mounted with guns killed 37 people in an attack on a market in North Darfur. The UN-African Union peacekeeping mission in Darfur (UNAMID), which is charged with protecting civilians and has a base 15 kilometers away at Tawila, turned back in its first effort to reach the site on the advice of a pro-government armed group and did not reach the market until nearly a week after the attack.

The incident underscores the need for the peacekeeping operations to interpret its protection mandate robustly and to insist on immediate access to areas where violations occur, Human Rights Watch said.

Violence has also increased inside camps for people who have been displaced by the conflict. At Kalma camp in South Darfur and at Hamadiya camp in West Darfur, tensions in July between supporters and opponents of peace talks, known as the Doha peace process, led to violence, killing 11 people.

The impact of the fighting between armed groups in Darfur and of government attacks on civilians has not been fully documented, in part because the government and rebels have repeatedly denied peacekeepers and humanitarian aid groups access to affected areas. Following violence in Kalma camp, for example, the Sudanese government blocked humanitarian organizations from the camp for several weeks.

Human Rights Watch has repeatedly urged leaders of the peacekeeping operation to increase human rights monitoring and public reporting and, where necessary, issue statements pressing Sudanese authorities to end specific abuses.

In September, the Sudanese government endorsed a new security and development strategy for Darfur, which the peacekeepers have publicly supported. The plan envisions the return of displaced people to their homes, but it does not contain clear measures to ensure their returns are voluntary, or that militias are disarmed and soldiers held accountable, Human Rights Watch said.

"Darfur cannot be developed unless there is real security," Peligal said. "The international actors need to press the Sudanese government to immediately end attacks on civilians, let humanitarian groups and peacekeepers operate effectively, and send people home only when they want. The government also needs to bring to justice those who have committed abuses in Darfur, including by cooperating with the International Criminal Court."