This month, nearly 600 drug addicts broke out of a rehabilitation center in the northern Vietnamese city of Haiphong. The addicts overpowered guards at the state-run treatment facility and made a break for it. "We were completely overwhelmed," a security guard told the Associated Press. "Forty of us were not able to prevent them, many with canes and bricks, from escaping." Videos on the Internet show crowds of escapees marching through city streets.

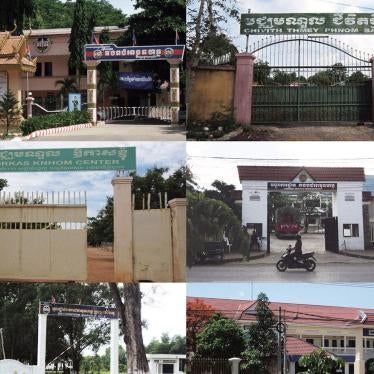

Why were hundreds of patients fleeing treatment? Because in Vietnam, "treatment" looks a lot more like forced labor, complete with beatings and years of involuntary detention. Like neighboring Cambodia, China, Laos, Malaysia, and Thailand, the government of Vietnam has adopted a "get-tough" approach to drug treatment rather than evidence-based treatment. In Vietnam, more than 100 government-run facilities detain between 35,000 to 45,000 people for extrajudicial sentences of up to four years.

Vietnamese in these treatment centers are engaged in what the government calls "therapeutic labor": long hours at menial jobs for below-market wages -- whatever's left, that is, after the centers deduct for the cost of their meager food and Spartan lodging. Those who fail to meet work quotas are beaten. Patients who violate center rules can be locked in solitary confinement. "[T]hey beat people up, kicked the face, kicked the chest," a former resident of a rehab center near Hanoi told the BBC in 2008. "Later, people were made to work very hard. They said work to forget the addiction, work is therapeutic."

Opium cultivation and smoking are not new phenomena in Vietnam. But with economic liberalization and increased migration since the 1980s has come greater economic polarization and drug abuse. It is estimated that there are more than 100,000 injecting drug users in the country today, and nearly one in three is HIV infected.

Drug treatment hasn't kept pace with increasing abuse, and aside from some small-scale programs, allowed by the government but largely funded by other donors, effective treatment is virtually nonexistent. Instead, the government emphasizes compulsory, institutionalized treatment that isn't just inhumane, but also next to useless. Government reports have said that 70 to 80 percent of those who spend time in a center return to drug use. Other estimates put the rate closer to 90 percent -- and when drug users do relapse, they have no place to go, especially not to a compulsory "treatment" center. According to a study published this spring in the Journal of Urban Health, drug users in Vietnam who have been in rehab centers are more likely to be infected with hepatitis C than those who have not. Another study found that detention and fear of police led to greater risk of HIV infection among Vietnamese users.

In fact, Haiphong's escapees probably stand a better chance on the outside, if they can stay there: The city is one of three in Vietnam that is piloting the use of methadone to manage opiate addiction, the preferred approach in most developed countries. Indeed, trials of methadone maintenance therapy were already successfully conducted in Hanoi in the mid-1990s. So why not increase the number of slots in the Haiphong methadone clinic and offer the escapees voluntary enrollment? The U.S. government could help ensure that those who escaped can access services by redirecting its funding, which currently goes to HIV-treatment programs inside these abusive centers (though not the centers themselves), to programs based in the community.

Indeed, were Haiphong to expand access to the community-based drug treatment services it already offers and add counseling, employment prospects, and housing assistance, the city could become a model of humane and sustainable treatment. Those who were only occasional drug users -- and who don't need drug addiction treatment in the first place -- are more likely to find meaningful work and social support networks in the community to avoid becoming addicted. Serious addicts and casual users alike are likely to find better HIV prevention programs and services in the community.

Drug rehabilitation should provide drug users with a chance to regain control of their lives, repair broken relationships, and overcome destructive addictions. Rehab in Vietnam ruptures the lives of drug users, severs social support, and pretty much guarantees a return to drug use after years of abuse. No wonder drug users are escaping.

Joe Amon is the Director of the Health and Human Rights division at Human Rights Watch.