“They Treat Us Like Animals”

Mistreatment of Drug Users and “Undesirables” in Cambodia’s Drug Detention Centers

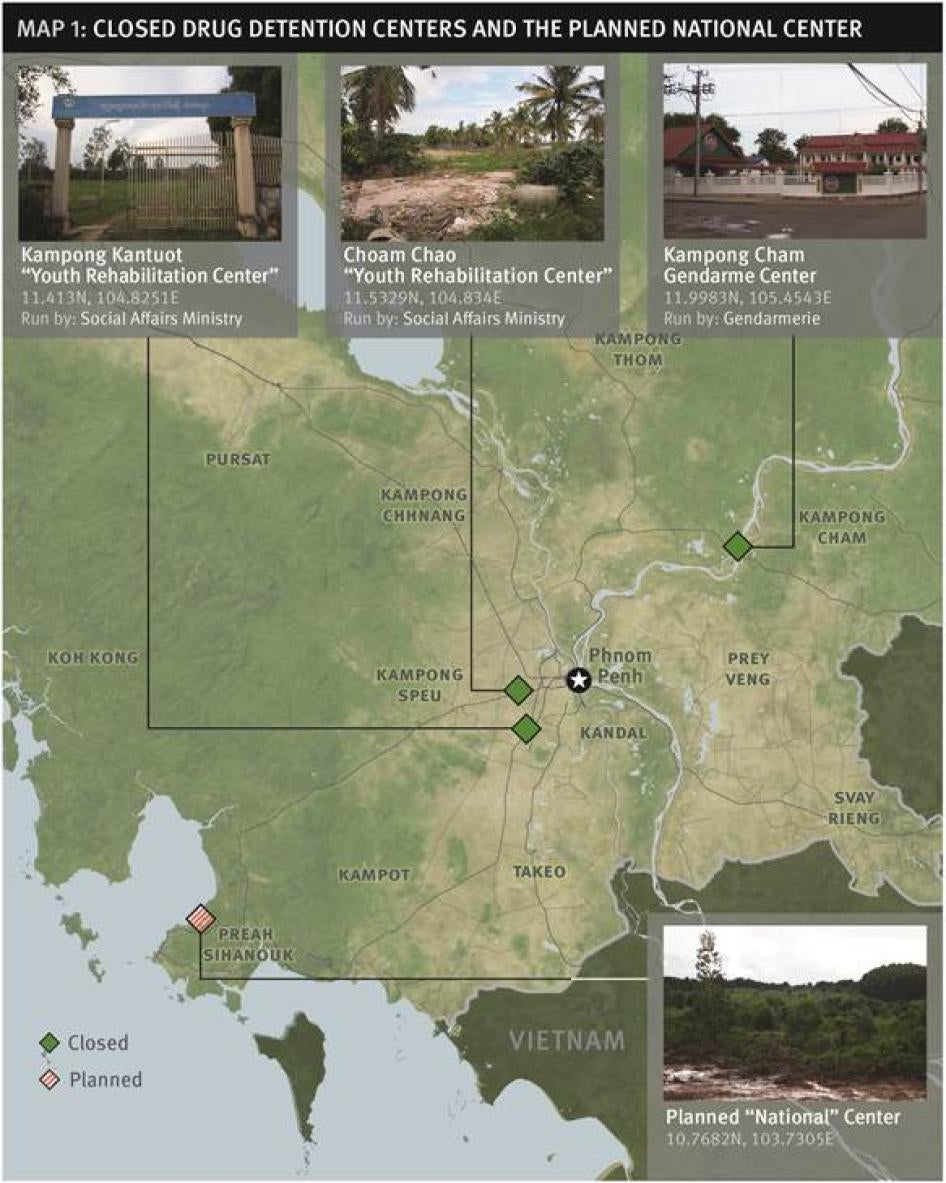

Map 1: Closed Drug Detention Centers and the Planned National Center

Map 2: Current Drug Detention Centers in Cambodia

Summary

Smonh is a slightly built, soft-spoken man in his mid-20s. When Human Rights Watch talked with him one evening in mid-2013, he was sitting quietly in a public park in Cambodia’s capital, Phnom Penh. He explained that he earns a living by collecting rubbish from the streets and selling it to traders for recycling.

His life had recently changed considerably for the worse. Park guards picked him up in early November 2012, about two weeks before US President Barrack Obama arrived in Phnom Penh for the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) summit that began on November 19. Smonh wasn’t told why he was detained. He was put in a large truck that evening, along with a dozen other people—sex workers, beggars, and street kids.

They were driven to a government facility on the outskirts of the city, Orgkas Khnom (“My Chance”), which is not a jail or prison but supposedly a place for people dependent on drugs to receive treatment and rehabilitation. Like many others in the truck, Smonh did not need drug treatment. He used to smoke the drug “ya ma”—methamphetamine—during his adolescence but he was proud that he had stopped using it four years ago of his “own free will.”

He told Human Rights Watch that staff at the center beat and abused him as well as the other detainees. After a few weeks, he and several other detainees resolved to escape: “I could not stand the whippings,” he explained. They managed to break out of their sleeping quarters during the night, and some managed to escape over the external wall. But when Smonh could not clear the barbed wire on top of the external wall, a guard knocked him to the ground with a shock from an electric baton. Detainee guards then savagely beat him until he lost consciousness. The next day his punishment continued.

They beat me like they were whipping a horse. A single whip takes off your skin. A guard said “I’m whipping you so you’ll learn the rules of the center!” … I just pleaded with them to stop beating me. I felt I wasn’t human any more.

Smonh was detained for around three months. Although he had stopped using drugs long before his detention in Orgkas Khnom, he resumed drug use shortly after release:

I feel crazy because of the beatings I received inside the center. Now I sniff a can of glue a day and, if I can afford it, I smoke ya ma. I am very angry because they treat us like animals.

There are currently eight drug detention centers spread throughout Cambodia that, at any point in time, collectively hold around 1,000 men, women, and children. Most are confined for three to six months— although some detentions last up to 18 months. According to government statistics, some 2,200 people were confined in these centers during 2012. The majority of detainees are young men between 18 and 25 years old, although at least 10% of the total population is children.

Torture and other ill-treatment in these centers are common, both as punishment and as a regular part of the “program.” Staff designate certain detainees as unofficial guards, who often beat each new arrival. Cruel assaults by staff appear routine: Buon, in his early 20s, fell out of step during a military-like march and was made to crawl along the ground as guards repeatedly hit him with a rubber water hose; Sokrom, a woman in her mid-40s, was beaten by guard with a stick for asking to go to the toilet—she said her face was swollen for weeks afterwards; Asoch, in his early 30s, watched the director of one center thrash a fellow detainee with a branch from a coconut palm tree until it broke.

Human Rights Watch has conducted research on Cambodia’s drug detention centers since 2009. The Cambodian government has shown callous disregard for the well-being of the thousands of mostly marginalized people—many of them children—who it sends to the facilities, where individuals are subject to vicious and capricious abuse. Simple mistakes like falling out of step while performing military-like drills or singing the wrong words in a marching song can subject the person to brutal punishment.

There should be no illusions: these centers are not intended to help those dependent on drugs.

On the contrary, Human Rights Watch has found the centers are a means to lock away drug users and those suspected of drug use with considerably less effort and costs than would be incurred by prosecuting people in the justice system and incarcerating them in prisons. Although current Cambodian drug laws have a few broad procedural safeguards to protect people from being forced into drug detention centers, they are flimsy and ignored.

Lack of due process protections means the centers are also convenient facilities to detain people whom the Cambodian authorities consider “undesirable”—such as homeless people, beggars, street children, sex workers, and people with actual or perceived mental or developmental disabilities—in sporadic crackdowns, often ahead of high-profile international meetings or visits by foreign dignitaries.

But the centers are not only convenient places for the authorities to corral those deemed objectionable; they also appear intended to punish people for the supposed moral failure of drug use—or of being homeless, a beggar, or a sex worker.

Four years ago, Human Rights Watch published “Skin on the Cable”: The Illegal Arrest, Arbitrary Detention and Torture of People Who Use Drugs in Cambodia. Drawing on interviews with people who had been held in drug detention centers between 2006 and 2008, it detailed various abuses including whippings, beatings, cruel punishments, sexual violence, and forced labor.

This report is based on interviews with 33 individuals who had been held in the centers since then (between mid-2011 and mid-2013). Arbitrary detention without due process continues: as in the earlier report, none of the people whom Human Rights Watch interviewed saw a lawyer or judge, or were brought to court at any time after their apprehension or during their detention in the centers. Torture in these centers also continues: former detainees told Human Rights Watch that they were beaten, thrashed with rubber water hoses, punished by being forced to crawl along stony ground or stand in septic water pits, sexually abused, and forced to work.

Cambodia’s drug detention centers differ considerably from place to place. In some parts of the country, centers (such as Phnom Penh’s Orgkas Khnom) are high-walled, prison-like facilities on the urban outskirts. In other places, a center may be within the same compound as the police or gendarmerie station. One center is even run by the Cambodian military on the grounds of its provincial headquarters.

Regardless of the type of center, detainees spend their nights locked in barrack-like rooms and are forced in the morning to perform exhausting physical exercises and military-like drills in the center’s car park or parade ground. At some centers the rest of the day is spent idly passing time, while some detainees are made to work in the center’s garden or kitchen. Those who refuse to work are subject to beatings.

Human Rights Watch learned of several centers that force detainees to construct new buildings on the grounds of centers, or send them as part of work gangs to build houses and, at one center, to help construct a new hotel. Several former detainees in Phnom Penh said they were involved in construction work on the house of the then-center’s director.

Since 2010, the number of centers in Cambodia has decreased from 11 in 2010 to 8 in 2013. Although the reasons for their closure were not made public, Cambodia closed one center—the Choam Chao “Youth Rehabilitation Center” in Phnom Penh— soon after the publication of “Skin on the Cable” as well as two relatively small centers.

However, the overall number of people held in them has stayed constant, and the closure of the three centers has been offset by the opening of a new women’s unit in the Orgkas Khnom center. More ominously, the government has also announced plans to build a “national” drug treatment center in Preah Sihanouk province, although as of mid-2013 construction was not yet underway. It is unclear whether Vietnam, which Cambodia has approached to finance the planned center, will indeed do so.

According to government data, at least 1 in 10 center detainees are children under 18. Some may use drugs, while others are street children who do not use drugs but are confined in the centers following operations to “clean the streets.” Children face the same abuses as adults while confined: they are held in the same rooms as adults; forced to perform exhausting physical exercises and military-like drills; and are also subject to abuse, including cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment and even torture.

Romchoang, for example, was an adolescent child when he was held in the military-run center in Koh Kong province for 18 months. He was locked in a room, chained to a bed for the first week of his detention, and later made to perform physical exercises each morning. Soldiers told him that sweating would help him recover from drugs. Soldiers beat him for falling asleep when he was meant to be sweeping the barracks.

Forcing people into “treatment” in drug detention centers violates many of their human rights, including protection from arbitrary arrest and detention, and cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment. The en masseprogram violates the right under international law to the highest attainable standard of health.

All medical treatment should be scientifically and medically appropriate, and of good quality. Human rights, as well as medical ethics, are grounded on the recognition of the right to autonomy and self-determination and the importance of informed consent. Compulsory drug dependency treatment should only be undertaken in exceptional crisis situations where accompanied by specific protections to ensure it is intended to return a person to a state of autonomy over their own treatment decisions; is of short duration and strictly time-bound; and is subject to regular review by an independent authority. Absent such conditions, there is no justification for compulsory treatment.

Locking up homeless people, sex workers, street children, or people with actual or perceived disabilities in drug detention centers is wholly without basis under international law.

These fundamental international legal violations mean that all individuals currently detained in Cambodia’s drug detention centers should be immediately and unconditionally released. To respect, protect, and fulfill the right to health of people with drug dependency, the government should expand access to voluntary, community-based drug treatment through the Ministry of Health with the involvement of competent nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). This expansion of voluntary treatment services should not be a precondition for closing the centers.

Cambodian and international law also require authorities to investigate credible reports of torture and other ill-treatment, and appropriately discipline or prosecute those responsible. The Cambodian authorities took no such steps following the publication of “Skin on the Cable.” Once again, Human Rights Watch calls on Cambodian authorities to promptly investigate these reports of torture and ill-treatment, and prosecute the perpetrators.

Former detainees, like Pram, said they understood why the abysmal state of Cambodian drug treatment could continue in plain sight and without consequence. Detained in Orgkas Khnom center for three-and-a-half months in early 2013, he said simply: “Because we have no rights.”

Recommendations

To the Government of Cambodia [1]

- Release all persons currently held in Cambodian drug detention centers, as their continued detention cannot be justified on legal or health grounds.

- Permanently close Cambodia’s drug detention centers, as they hold people in violation of international law.

- Immediately suspend all preparations to build a new “national” drug detention center.

- Ensure a prompt, thorough, and impartial investigation and appropriate prosecutions of those responsible for serious abuses in connection with drug detention centers, including arbitrary arrests, torture, cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, and forced labor.

- Stop the arbitrary arrest and detention of people who use drugs and others deemed “undesirable,” such as homeless people, beggars, street children, sex workers, and people with actual or perceived disabilities.

To the Ministry of Health

- Expand access to voluntary, community-based drug dependency treatment and ensure that such treatment is medically appropriate and comports with international standards.

To the Government of Vietnam

- Provide no funding, programming, or activities directed to assisting Cambodia’s planned “national” drug detention center (or any other drug detention center) that will support policies or programs that violate international law, including the prohibition on forced labor.

To the Country Offices of United Nations Agencies and Cambodia’s Bilateral and Multilateral Donors

- Publicly call for the immediate release of all persons held in Cambodian drug detention centers.

- Publicly call for: an end to human rights violations that occur in Cambodian drug detention centers; credible and impartial investigations into allegations of abuses at these centers; and holding to account those responsible for violations.

To Foreign Embassies and United Nations Agencies in Phnom Penh

- In advance of international meetings or visits by foreign dignitaries, publicly call on the Cambodian government to not undertake operations to “clean the streets” of drug users, homeless people, beggars, sex workers, street children, and people with actual or perceived disabilities.

- Form a working group, comprised of senior staff of foreign embassies and UN agencies, tasked to coordinate joint advocacy to dissuade Cambodian authorities from operations to “clean the streets” in advance of international meetings or visits by foreign dignitaries, and to press for the immediate release of any persons arbitrarily detained as a result of such operations.

Methodology

This report is based on information collected during field research conducted in Cambodia between May and July 2013. Human Rights Watch interviewed 33 people previously held in government drug detention centers. These include 13 people who currently use (or formerly used) drugs and who had been recently detained one or more times in a drug detention center; and 20 people who did not identify themselves as drug users, but who had nevertheless been recently detained one or more times in a center because they were homeless, beggars, street children, or sex workers. All individuals interviewed for this report had been detained in the 24-month period between July 2011 and June 2013.

Eleven of the former detainees were adult women. Three of the former detainees were children (under 18 years of age) at the time of their detention (one boy and two girls). All three children were adolescents, although their precise ages have not been included in order to protect their identities.

Human Rights Watch interviewed individuals formerly held in six of the eight current government drug detention centers, including centers run by the municipality of Phnom Penh, the Cambodian military, the gendarmerie, and police. Interviewees include people formerly detained in centers situated in the following provinces: Battambang, Banteay Meanchey, Siem Reap, Koh Kong, and the capital, Phnom Penh. Human Rights Watch was unable to identify and meet with individuals previously held in one center in Preah Sihanouk province and one center in Banteay Meanchey province.

Interviewees also included four people previously detained in one center run by the Ministry of Social Affairs, Veterans and Youth Rehabilitation (the Ministry of Social Affairs) at Prey Speu near Phnom Penh, although this center is not officially listed as a drug treatment center. Our research indicates that people who use drugs (as well as others) were regularly detained there during 2012.

We recruited interviewees in places where people who use drugs, homeless people, beggars, street children, and sex workers often live or work. All interviewees provided oral informed consent to participate. Interviews were conducted in private and individuals were assured that they could end the interview at any time or decline to answer any questions without consequence. Interviews were semi-structured and covered a number of topics related to illicit drug use, arrest, and detention. Where the interviewees spoke Khmer, interviews were consecutively interpreted between English and Khmer. The identity of these people has been disguised with randomly-selected pseudonyms and in some cases, certain other identifying information has been withheld to protect their privacy and safety.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed five current or former staff members of NGOs and UN agencies with knowledge and experience regarding Cambodia’s system of drug detention centers.

This report follows research undertaken between February and July 2009 and published in the report “Skin on the Cable”: The Illegal Arrest, Arbitrary Detention and Torture of People Who Use Drugs in Cambodia in January 2010. That report was based on interviews with 74 people— including 63 who had been detained one or more times in a drug detention center between 2006 and 2008. It also builds on research undertaken between July 2009 and April 2010 and published in the report Off the Streets: Arbitrary Detention and Other Abuses against Sex Workers in Cambodia in July 2010. That report was based on interviews with 94 female and transgender sex workers.

Where available, secondary sources—including media reports and reports from government sources or other organizations—have been included to corroborate information from former detainees and current or former staff members of NGOs and UN agencies.

In September 2013, Human Rights Watch wrote to the head of Cambodia’s National Authority for Combatting Drugs (NACD) to request information on Cambodia’s drug detention centers and solicit his response to violations documented in this report. This correspondence is attached in Annex 1. By the time this report went to print, Human Rights Watch had not received a response.

Also in September 2013, Human Rights Watch wrote to Vietnam’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs regarding Cambodia’s request for Vietnamese assistance regarding the planned “national” drug treatment center. This correspondence is attached in Annex 2. By the time this report went to print, Human Rights Watch had not received a response.

I. Background

This is Human Rights Watch’s second report on abuses in Cambodia’s drug detention centers. In January 2010, Human Rights Watch published “Skin on the Cable”: The Illegal Arrest, Arbitrary Detention and Torture of People Who Use Drugs in Cambodia. Drawing on interviews conducted in 2009 with 63 people who had been detained between 2006 and 2008, the report documented torture and cruel and inhuman treatment inflicted on drug users and other people considered by government authorities to be “undesirable.”

“Skin on the Cable” detailed how people held in the centers had been whipped with twisted electrical wire, beaten, forced to perform painful physical exercises, made to work, and sexually abused. The report concluded that the mainstays of drug treatment in Cambodia’s centers were exhausting physical exercises and military-like drills, violating the requirement under international law that health facilities and services be ethically acceptable, and scientifically and medically appropriate.

Drug Users in Cambodia

Estimates of the number of people who use drugs in Cambodia differ widely. The NACD Annual Report for 2012 claimed there were officially 4,057 drug users in Cambodia in 2012, although it recognized the actual number is likely to be higher.[2] For its part, the UN Office on Drugs and Crime, UNODC, has publicly cited reports estimating as many as 46,000 people in Cambodia use drugs.[3]

The primary response from government officials was to dismiss Human Rights Watch’s report as untrue.[4] The spokesperson for the Ministry of Social Affairs was quoted as saying: “I think these criticisms [of the centers] lack basic evidence.… All centers are working in a humanitarian fashion.”[5]

However, a number of comments that government officials provided to both local and international journalists inadvertently supported the report’s findings. For example, a Ministry of Interior spokesman was quoted as stating: “[People in detention] need to do labor and hard work and sweating—that is one of the main ways to make drug-addicted people to become normal people.”[6] Another article quoted the commander of the gendarmerie in Banteay Meanchey province as denying torture at his center, but confirming that some people in the center were forced to stand in the sun or "walk like monkeys" [i.e. on all fours] as punishment for attempting to escape.[7] An international news broadcaster entered one center and managed to film young children working there before being ordered to leave.[8]

Two months after the report was released, Prime Minister Hun Sen lashed out indirectly at Human Rights Watch in a speech to Cambodian narcotics officials, saying: “Some human rights organizations, lacking in rational consideration, take the chance to blindly attack without seeing the government’s charity.” The prime minister conceded that the centers do not offer model treatment, but justified the system as the best the country could offer.[9]

In May 2010, the grouping of UN agencies in Cambodia issued a “common viewpoint” on drug detention centers in Cambodia. It concluded that “there is no evidence that centres operated by the Royal Government of Cambodia … operate in accordance with evidence and good practice; on this basis there is no reason for the centres to remain open.”[10]

Without naming Cambodia specifically, 12 UN agencies issued a joint statement on drug detention centers in March 2012. The statement noted:

The deprivation of liberty without due process is an unacceptable violation of internationally recognised human rights standards. Furthermore, detention in these centres has been reported to involve physical and sexual violence, forced labour, sub-standard conditions, denial of health care, and other measures that violate human rights. There is no evidence that these centres represent a favorable or effective environment for the treatment of drug dependence, for the “rehabilitation” of individuals who have engaged in sex work, or for children who have been victims of sexual exploitation, abuse or the lack of adequate care and protection.[11]

The UN agencies called on states with drug detention centers “to close them without delay and to release the individuals detained. Upon release, appropriate health care services should be provided to those in need of such services, on a voluntary basis, at community level.”[12]

Drug Detention CentersIn Asia, the facilities described here as drug detention centers go by a variety of names: compulsory treatment centers, drug rehabilitation centers, detoxification centers, or (in Vietnam), “Centers for Social Education and Labor.” They are common in China and Southeast Asia, with an estimated combined population of 350,000 detainees. [13] These facilities may differ greatly by, and even within, a country. However, regardless of their name, centers that hold people against their will for drug dependency treatment should be considered “drug detention centers” operating outside international law. Many people are held in such centers without ever seeing a lawyer or a judge, or without having means to challenge the legality of their detention. Even when such centers are enabled by national legislation (and where that legal framework is fully respected in practice), detention in such centers is arbitrary, and violates international law because it is a medically and scientifically inappropriate response to any actual clinical need for treatment of drug dependence. [14] The various restrictions on individual rights resulting from detention in such centers are not strictly necessary, nor the least restrictive means, to achieve the purpose of drug treatment. [15] |

Abuses in drug detention centers in Cambodia were specifically taken up by the Children’s Rights Committee, the UN body responsible for upholding the Convention on the Rights of the Child, in 2011. The committee called on the government to release “without delay” children in detention centers and urged “prompt investigation into allegations of ill-treatment and torture of children in those centers and the judicial prosecution of all perpetrators.”[16]

Cambodian and international law obligates Cambodian authorities to release people currently held in the centers, as their continued detention cannot be justified on legal or health grounds. It also requires Cambodian authorities to carry out thorough and impartial investigations into allegations of serious human rights violations. Those implicated in arbitrary arrest and detention, torture and ill-treatment, and forced labor in drug detention centers should be appropriately disciplined or prosecuted.

In the nearly four years since the release of “Skin on the Cable,” the Cambodian authorities have not met calls to release all detainees from the centers, investigated reports of torture and other criminal acts, or held any perpetrators accountable.

In 2010, the Cambodian government authorized small-scale voluntary, community-based drug treatment projects in Phnom Penh and in Banteay Meanchey province.[17] Project activities have since expanded to two other provinces, Battambang and Stung Treng.[18] Government officials have made it clear that such projects are not “alternatives” to drug detention centers, as at least one of Cambodia’s international donors, UNODC, has claimed.[19] The deputy governor of Banteay Meanchey province told local media, “We need both”—community-based drug treatment and drug detention centers.[20]

In early 2012, Cambodia revised its Law on the Control of Drugs. Despite the credible reports of widespread abuses related to the centers, and repeated calls for their closure, new provisions in the law replaced the existing measures on compulsory treatment in a substantially similar form. The law contains broad powers for a prosecutor to compel a person into treatment. For example, the law establishes that:

Treatment can be compulsory if it is regarded as a necessary measure to protect the general interests of, and is of benefit to, the drug addict. Treatment can also be compulsory if a drug addict is lacking the capacity to express his/her intention to accept voluntary treatment.[21]

The law remains overly broad, containing few procedural safeguards against abuse of the means by which people can be sent into treatment. Despite this, the minimal procedures required by the law before a person can be compelled into treatment are, in practice, ignored by those running the centers and the authorities rounding up people.

List of Government Drug Detention Centers in Cambodia

|

N° |

Name of Center |

Province |

Run by |

Capacity |

|

1 |

Orgkas Khnom center [“My Chance”] |

Phnom Penh |

Phnom Penh Municipality |

Approx. 400 |

|

2 |

Gendarme center |

Battambang |

Gendarmerie |

Approx. 100 |

|

3 |

Bavel Police center |

Battambang |

Police |

Approx. 100 |

|

4 |

Phnom Bak center |

Banteay Meanchey |

Social Affairs |

Approx. 120 |

|

5 |

Gendarme center |

Banteay Meanchey |

Gendarmerie |

Approx. 200 |

|

6 |

Police center |

Siem Reap |

Police |

Approx. 50 |

|

7 |

Gendarme center |

Preah Sihanouk |

Gendarmerie |

Approx. 40 |

|

8 |

Military center |

Koh Kong |

Military |

Approx. 30 |

According to the government’s National Authority for Combating Drugs (NACD), during 2012 at least 2,223 people passed through seven centers.[22] However this figure almost certainly underreports the actual number of people in detention.

Human Rights Watch is aware of at least one additional drug detention center not on the NACD’s 2012 list of centers: a center run by the Cambodian military located on the base of the Koh Kong provincial military headquarters near Koh Kong town.[23]

Although incomplete, the NACD’s 2012 data nevertheless provides some insights into who is locked inside Cambodia’s centers. Of the 928 people recorded in the seven centers at the beginning of 2013, 98 (11 percent) were children (between 10 and 17 years old), while the majority (532 out of 928, or 57 percent) were between 18 and 25 years old. 67 (or 7 percent of the total) were female.

The most common drugs reported being used were methamphetamine in crystallized form (698, or 75 percent), methamphetamine (151, or 16 percent), and glue (49, or 5 percent). “Street children” accounted for 67 people in the centers (7 percent) and “women at entertainment places” (a common euphemism for sex workers in Cambodia) accounted for 21 (2 percent). A total of 283 individuals in the centers (30 percent) were classified as having “no real profession.”[24]

The number of government detention centers in Cambodia has decreased from 11 in 2010 to 8 in 2013— although the total number of individuals in detention each year remains roughly constant.[25]

One of the three centers closed since 2010 was the Choam Chao “Youth Rehabilitation Center,” which was situated in Phnom Penh and run by the Ministry of Social Affairs up until 2010. The center had the capacity to detain approximately 100 people. It ceased to operate in mid-2010 after the United Nations Children’s Fund, UNICEF, which had provided funding since 2006, confirmed reports of abuses against detainees and stopped funding the center.[26] In late 2012, the center’s buildings were demolished.

The frond-strewn floor of a former building inside the Choam Chao “Youth Rehabilitation Center” in Phnom Penh. Cambodia closed the center in 2010. © 2013 Human Rights Watch

The other two centers closed since 2010 include the gendarme-run center in Kampong Cham province and the center run by the Ministry of Social Affairs in Kandal province. Both were relatively small centers, holding a few dozen people.[27]

The impact of the closure of these three centers has been offset by the construction of a new unit designated for women and girls in the Orgkas Khnom center. Large numbers of women and girls were not detained in drug detention centers up until 2011. Orgkas Khnom opened a 10-room building for female drug users in May 2011.[28] According to local media, construction of the unit was funded by the Bank for Investment and Development of Vietnam.[29] According to NACD’s data, at the beginning of 2013 there were 61 females (out of 67 females held in seven drug detention centers) confined there.[30]

Additionally, while it has never been listed by the NACD as a drug center, individuals told Human Rights Watch that one other center (Prey Speu near Phnom Penh, run by the Ministry of Social Affairs) was regularly used to detain people who use drugs, as well as homeless people, beggars, street children, sex workers, and people with actual or perceived mental or developmental disabilities, during 2012.[31]

The NACD’s Annual Report for 2012 describes several recent steps that the Cambodian government has taken to prepare for a new “national” center in Preah Sihanouk province. The NACD reported that it had prepared a five-year strategic plan (2014-2018) for the center and that financial provisions have been included in the Public Investment Program 2013-2015. It also reported that it had drafted a memorandum of understanding between the governments of Vietnam and Cambodia covering the center’s construction, and sent the draft to the Vietnamese government.[32]

Local media first reported the Cambodian government’s intention to build a national center in March 2010. The then-secretary general of the NACD was reported as stating that the center would have the capacity to hold 2,000 people and would be open by 2015.[33] Land for the center was reportedly donated by Cambodian businessman and Cambodian People’s Party senator Mong Reththy, whose agricultural plantations surround the plot.[34]

In December 2010, the Council of Ministers approved the plan.[35] At that stage, the same NACD official was reported as saying that the Cambodian government had requested US$2.5 million financial support from the Vietnamese government to build the center.[36] In July 2013, Human Rights Watch visited the location of the planned center in Preah Sihanouk province and did not find any evidence of construction.

Human Rights Watch is concerned by the prospect of Vietnam providing assistance to Cambodia in the realm of drug treatment, given our findings of forced labor and other abuses in drug detention centers in Vietnam. The Human Rights Watch report The Rehab Archipelago found that forced labor is central to the purported “treatment” of people in drug detention centers in Vietnam.[37]

According to Vietnamese government regulations, labor therapy [lao dong tri lieu] is one of the official five steps of drug rehabilitation.[38] In comparison with Cambodia—where detention is usually three to six months—a person can spend up to four years in Vietnam’s drug detention centers.[39] Rates of relapse to drug use after “treatment” in Vietnam’s centers have been reported at between 80 and 95 percent.[40]

II. Findings

I couldn’t stand it; it was too brutal in there.

—Sok, a man in his 20s who escaped from Orgkas Khnom after six weeks, Phnom Penh, July 2013

Cambodia’s drug detention centers hold people who use drugs, those suspected of using drugs, and a wide range of other individuals considered “undesirable” by authorities. Homeless people, beggars, street children, sex workers, and people with actual or perceived disabilities are also locked up on a routine basis, often to “clean the streets” for visiting foreign dignitaries or international meetings.

Physical violence against male and female detainees is commonplace. Center staff punch and kick people, whip them using rubber water hoses, hit them with bamboo sticks or palm tree branches, or shock them with electric batons. They punish people with physical exercises intended to cause intense physical pain, such as making male detainees roll or crawl over the ground without even a shirt to protect them from sharp stones and rocks.

Much of the day-to-day control of people in the centers is carried out by detainees designated by staff to act as guards. These detainee guards also beat people, often on the direct orders of staff or while staff watch.

All of the forms of ill-treatment described below are strictly prohibited under international law. Some ill-treatment—such as whippings, blows, and electric shocks—constitutes torture. Rape and other forms of sexual assault in detention also amount to torture.

Orgkas Khnom detains women and girls in a separate building to men and boys, although some staff in this unit are men. In other centers, women and girls are held in the same facilities as men and boys. At least 1 in 10 of people in the centers is a child. They are held in the same rooms as adults, and are forced to perform exhausting physical exercises and military-like drills. Like adults, they are also subjected to physical abuse.

Many detainees are made to work. In some cases this forced labor is related to the functioning of the center, such as growing vegetables or working in the kitchen; those who attempt to refuse to work are beaten by detainee guards. In other cases, detainees are used to construct new buildings in the centers, or sent in work gangs to construction sites at houses or, in one case, a hotel. While the types of labor might differ from center to center, all forms of forced labor in the centers are prohibited by international and Cambodian law.

Locking Away Cambodia’s “Undesirables”

Procedures for confining people in Cambodia’s drug detention centers are perfunctory. None of the people whom Human Rights Watch interviewed in the course of researching this report saw a lawyer, judge, or court at any time before or during their detention.

People are usually picked up by security guards, police, or gendarmes. In Phnom Penh, police then take the person to the local police station or the municipal Social Affairs office, then transfer them to a center (usually Orgkas Khnom). In other locations, police or gendarmes usually take the person directly to the center, which in some cases is within the same compound as their own station.

Cleaning the Streets of People Who Use Drugs

In Cambodia, people who use drugs are highly stigmatized. In July 2012, when Human Rights Watch reiterated its call for Cambodia to close its drug detention centers, local media reported the then-deputy secretary-general of the NACD as saying: “Why do they just always recommend closure? Do they want the drug users walking around?”[41]

Buon, in his early 20s, told Human Rights Watch he is a drug user. He was picked up in early 2013 when he and some friends fell asleep in a park during the day.

The police did not explain anything. I was questioned in the Daun Penh district police office then they sent me to the municipal Social Affairs office where they did a report about me. Then they sent me to Orgkas Khnom for three months. I never saw a lawyer or a judge.

Buon was subsequently held for three months.[42]

Sok, in his early 20s, said that he was picked up in early 2013 while sitting in a park during the afternoon with friends. He told Human Rights Watch:

The police said that they had some questions for us and that they would then let us go. But I was driven to the district police post on a motorbike and then they drove us to Orgkas Khnom in a caged truck.

Sok was adamant that Orgkas Khnom “is not a center for drug treatment.” He said he spent six weeks confined in Orgkas Khnom before he escaped.[43]

Champey spent three months in Orgkas Khnom in early 2013. In his mid-20s, he is a heroin user who was picked up one day in a park in Phnom Penh at midday. He told Human Rights Watch he was arrested by municipal Social Affairs officers:

They only told me that I should not sleep in the streets and that I should get inside their truck. First I went to the Daun Penh district police station, then the municipal Social Affairs office, then they took me to Orgkas Khnom.[44]

Some people who use drugs are detained in centers on the request of relatives. Beng, in his early 20s, uses methamphetamines. Describing his time in the police-run center in Siem Reap, Beng told Human Rights Watch he “felt homesick and scared.” He was detained after his mother paid the police $300 to hold him for six months. He told Human Rights Watch:

The police came to arrest me at my house. It wasn’t voluntary— I had to put my thumb print on some paper. The paper had my name on it but I don’t know what it said because I don’t know how to read. I was taken to the center the next morning.[45]

Some family members who are desperate for treatment options for a relative dependent on drugs might request police and other authorities lock up that person on the mistaken belief that the centers offer a therapeutic process. Government authorities hold out the centers as providing drug treatment (and, in many parts of Cambodia, the only available form of treatment). Detention costs between $50 and $200 per month, an amount usually paid by family members directly to the center.[46] In general, the detainee will be released once the family stops paying.

However, there are no protections for the person at risk of detention to ensure that family members do not act out of embarrassment or a desire to have the family member out of their lives for some time. Human Rights Watch saw an admission form from late 2009 for one child held in the center on the military base in Koh Kong. Addressed to the center’s director, the form was signed by the child’s mother, the village head, and the commune head. The form contained the following justification for detention by the child’s mother:

My son … behaves strangely and abnormally; he walks with a group of kids who use drugs. Consequently, my son’s behavior has become stubborn and disobedient. He argued verbally with his siblings and his mother. He went out for a walk and didn’t return home. Seeing this situation, I would like to send him to the rehabilitation center.[47]

The child was subsequently held by the military in Koh Kong province for two months.

Detaining Other “Undesirable” People

People who use drugs in Cambodia are not the only people considered “undesirable” by authorities. In early 2012, local media quoted an official at Phnom Penh’s Social Affairs department explaining that beggars and sex workers make the city “messy” and that rounding them up was necessary to “keep public order and make the city beautiful for ASEAN.” He said, “We’ve taken them for training.”[48] In fact, homeless people, beggars, street children, sex workers, and people with actual or perceived disabilities are routinely held in drug detention centers.

Homeless People

Eysan, in his early 30s, told Human Rights Watch he lives with his family on the streets of Phnom Penh. He was arrested by park guards while drinking wine with friends in early 2013:

They parked the truck near the riverside and asked us to get into the truck. They didn’t tell us why. We were driven in the Daun Penh district police station then another truck arrived —this truck belonged to the Social Affairs ministry—and we were driven to Orgkas Khnom center.

While he was detained, Eysan’s wife (who was pregnant at the time) began begging in order to support herself. Eysan told Human Rights Watch: “My wife had to become a beggar, but she didn’t have experience with this. I cried each night thinking about her.” Asked why he thought he was confined in Orgkas Khnom, Eysan replied, “They think we are disgusting because we live on the street.”[49]

Bopea is a homeless woman in her late 20s who was seized by the police after sleeping on the streets. She spent two weeks in Orgkas Khnom before managing to escape. Like other individuals in Orgkas Khnom, Bopea was made to perform physical exercises and military-like drills while detained. She told Human Rights Watch:

The trainer said the exercises were to make us detoxify from drugs by sweating. I told the trainer I did not use drugs but everyone had to do the exercises. It was ridiculous.[50]

An “intervention” truck from the Daun Penh district police in Phnom Penh. Such trucks are used to transport the police who carry out “street sweeps” of drug users and other people considered “undesirable” by authorities. © 2013 Human Rights Watch

The authorities confine homeless women and girls in a number of centers around Cambodia.[51] For example, Srab, in her early 40s, told Human Rights Watch she is a homeless woman who has never used drugs. She was held for four months in the gendarme-run center in Battambang in early 2012 after being picked up while collecting rubbish for recycling in a local market place. She explained: “I told them I didn’t need to stop using drugs but they sent me to the center anyway and made me perform physical exercises.”[52]

Street Children

Although the NACD Annual Report for 2012 is incomplete (as it lists only seven of the eight centers in Cambodia), it notes that of the 928 drug users recorded in these seven centers at the beginning of 2013, 98 were children between 10 and 17 years old. It categorizes 67 people in the centers as “street children” (and does not specify the nature of the other recorded children).[53]

Romchoang was an adolescent child when he was detained in the military-run center in Koh Kong province for 18 months. He was kept in the same room as approximately 20 other people, some of whom he said were 12 or 13 years old; others were adults. He had to perform military-like exercises each morning. Romchoang told Human Rights Watch that, like other people in the center, he was chained on arrival:

Once inside, you cannot leave the military barracks. All newcomers are chained for about a week to prevent them from running [away]. I was chained around my ankle to the foot of my bed, inside the room. It was so difficult not to be able to walk around.[54]

Asoch, in his early 30s, was detained in Orgkas Khnom for two weeks at the end of 2012. He told Human Rights Watch that he was held alongside children in that center:

There were maybe eight children who were 12 or 13 years old, and maybe six of them were 14 or 15. A few are also 16 or 17. They are detained in the same room as adults. Like adults, they did exercises to sweat out the drugs and were hit by the detainee guards if they made mistakes.[55]

A number of other people told Human Rights Watch that children were detained in the same room as adults in the centers.[56]

The NACD Annual Report for 2012 asserts that no children under the age of 10 were confined in the seven centers covered by that report.[57] However, Human Rights Watch talked with individuals who described being held alongside children as young as 6, while others told Human Rights Watch they were detained along with baby children.

For example, Phoatrobot was detained in the police-run center in Siem Reap for two weeks in mid-2012 for begging. She was arrested along with her young child and told Human Rights Watch that there were three other young children and babies in the center, also held when their parents were seized for begging.[58] Meak, in his mid-20s, was held for four-and-a-half months in the police-run center in Bavel district, Battambang province. He told Human Rights Watch that the center also held children aged 6, 8, and 9 years old.[59]

Sex Workers

Human Rights Watch has previously documented how sex workers in Cambodia face a wide range of abuses, including beatings, extortion, and rape, at the hands of authorities.[60] In some parts of the country, sex workers may be held at drug detention centers for short periods of time as a form of extortion. For example, Kadeurk, a sex worker in her 40s, said the authorities detained her in the police-run center in Siem Reap three times in late 2012. She said:

I was released the next morning each time. They said, “If you don’t pay us you won’t be able to leave.” I paid the police five dollars and they released me. They said it was a fee for the paper and the ink of the form to release me.[61]

Since 2011, the Orgkas Khnom center near Phnom Penh has had a separate facility to hold women and girls. According to government data, around 60 women and girls were held there at the beginning of 2013.[62] Women held at the center told Human Rights Watch that the women’s unit in Orgkas Khnom is used to confine female drug users, sex workers, female beggars, and homeless women and girls.[63]

Roseal, a sex worker in her late 20s, said she was held there for a week in early 2013. Altogether she said she had been detained in Orgkas Khnom “five or six times” over the last few years:

They arrest sex workers every day. When they arrested me they said I was not allowed to do this business in the park. The district police transferred me to the municipal Social Affairs office where I spent one night, then I was sent to Orgkas Khnom.

In her words, “We didn’t do anything wrong but we were locked up like prisoners.”[64] Aural, a sex worker in her early 30s, was held there for two weeks in early 2012.[65] Porvang, also a sex worker in her early 30s, was detained there for three months in early 2013.[66]

People with Actual or Perceived Disabilities

Government drug detention centers also detain some people with actual or perceived disabilities. In the centers, they experience verbal and physical abuse and do not have access to the healthcare services they may need. Palkum was detained in the gendarme-run center in Battambang for two weeks in early 2013. He told Human Rights Watch:

There were two crazy people in the center with me. They were locked in the room day and night and only during the exercise period could they leave the room. The gendarmes told them, “When you leave here, don’t go wandering away from home! Don’t go on the street!” But they just smiled without understanding.[67]

Some people described to Human Rights Watch how people with actual or perceived disabilities were subject to cruel physical abuse by staff and other detainees. Kronhong was held for one month in the police-run center in Siem Reap in early 2013. She told Human Rights Watch about one elderly man who had convulsions:

He was shaking and foaming at the mouth, screaming. The policeman said “Stop screaming! Stop making so much noise!” The police beat him with a metal bar and his mouth was gagged with paper so he couldn’t scream. I saw beatings like this three or four times with different crazy people while I was in the center.[68]

Reatrey, in his mid-30s, was held for three months at the Orgkas Khnom center the end of 2012. He told Human Rights Watch about the physical abuse of people with actual or perceived disabilities in that center:

They just sit on their own. Sometimes they eat other people’s leftovers, or eat the garbage. They speak only a few words. People beat them every day for fun: kids punch them in the head or kick them in the buttocks. The staff also beat them in this way—everyone beats them.[69]

Street Sweeps for Foreign Dignitaries

Government campaigns to detain drug users, beggars, homeless people, street children, sex workers, and people with actual or perceived disabilities intensify before and during international meetings or visits by foreign dignitaries.

Street sweeps of “undesirable” people for the three main ASEAN meetings that took place in Phnom Penh during 2012 were widely reported in Cambodian news sources. For example, one local newspaper reported a local government spokesperson’s statement that before the ASEAN summit held in Phnom Penh on April 3-4, 2012, the authorities arrested 108 homeless people, beggars, and child glue sniffers and transferred them to the municipal Social Affairs office in Phnom Penh “for further measures.”[70]

Another article cited a local government official who detailed the arrest and transfer to the same office of 73 homeless people, child glue sniffers, and sex workers a few days prior to an ASEAN ministerial meeting in Phnom Penh on July 9-13, 2012.[71] An article from November 2012 noted a local government official’s claim that 38 sex workers were arrested and transferred to the municipal Social Affairs office in Phnom Penh “to maintain public order” during the ASEAN summit held from November 15 to 20, 2012. The article mentioned that over 200 homeless people, sex workers, beggars, and child glue sniffers had been detained during the previous month.[72]

A number of sex workers and homeless people told Human Rights Watch they were held in detention centers immediately prior to various ASEAN meetings in Phnom Penh in 2012.[73]

Thnong was a homeless adolescent child when picked up for sleeping on the streets in early 2012; she said that she was detained along with 20 other people —including drug users, beggars, and rubbish recyclers— as part of what she was told was a campaign “to beautify the capital for the ASEAN summit.” Thnong was held in Prey Speu for a week:

The security guards and the district police who work near the Royal palace said to me “We need to clean the streets now: no one is allowed to sleep in the streets.” They said that foreign delegations at the ASEAN meetings will check to see if Cambodia is an orderly country.[74]

Ches, in his early 20s, was arrested while sniffing glue. He said that the police told him that the motivation for his arrest was the upcoming ASEAN meeting. Ches said:

They clean beggars off the streets of Phnom Penh when there is a foreign delegation that visits. They arrested five men and five women that night: all went into the truck. The police chief in the district police office said, “We have to arrest you because there is a big meeting soon.”

Ches said he was subsequently detained for six months in Orgkas Khnom.[75]

Thmat, in her late 20s, works as a street vendor and sleeps on the streets at night. District police officers picked her up a month before the November 2012 ASEAN meeting. The truck that took her to Orgkas Khnom held approximately 30 other homeless people, beggars, street children, sex workers, and drug users. Shortly after arriving at Orgkas Khnom, she tried unsuccessfully to challenge her detention:

I’m not a drug user. I asked “Why are you detaining me?” They said, “To correct you! You should stop sleeping in the streets.” I said, “I did not do anything wrong or illegal in the streets.” But the director of the center said I would stay longer if I kept on complaining to them in this way.

Thmat was held for three months in Orgkas Khnom.[76]

Physical and Sexual Abuse

Many detainees try to escape from the centers because of the ill-treatment and poor conditions, despite knowing the authorities will brutally punish them if they are recaptured.

Smonh, whose story appears in the summary of this report, was one of a group of detainees who tried to escape from Orgkas Khnom one night. He was among those recaptured by staff and then beaten by five detainee guards until he lost consciousness (which he only regained at 1 p.m. the next day). He told Human Rights Watch:

When I came round both hands were tied with rope behind my back and both my ankles were chained. Those of us who had been captured were not given any food for hours. At 7 p.m. we were taken out of the room to be tortured. We had to do eight military exercises: we had to leopard crawl forward on our knees and elbows, then we had to hold our hands over our chests and roll ourselves along the ground lengthwise.… While we did these exercises they beat me like they were whipping a horse. A single whip takes off your skin. A guard said “I’m whipping you so you’ll learn the rules of the center!” We were all crying. I just pleaded with them to stop beating me. I felt I wasn’t human any more.

He was then taken back to his room where detainee guards continued to beat him. He told Human Rights Watch that for four or five days afterwards, he was coughing blood. “They treat us like animals,” he said. “If they thought we were humans, they wouldn’t beat us like this.”[77]

Asoch witnessed a similar beating during his detention for two weeks in Orgkas Khnom in late 2012. He described what happened to a person caught trying to escape:

First the detainee guards beat him. Then they made him kneel down and the center director whacked him with the branch of a coconut palm tree over his back, many times, until the branch broke. The guy screamed in pain- it was pitiful to see. The director cursed him and said, “If you try to escape again, I will keep you longer than three months!” Then he had to take off his shirt and crawl on his stomach along the ground; it was back and forth for 50 meters about 10 times. He was bleeding on his forearms, elbows, and knees. Then he had to kneel outside in the sun until lunch, until finally they locked him up in his room.[78]

Romchoang was an adolescent child when detained in the military-run center in Koh Kong for 18 months. He told Human Rights Watch:

There was a cage in the center: it has concrete on the top and iron bars on two sides. It’s not high, maybe 1.75 meters high, and 4 meters by 6 meters. One detainee was rearrested after he tried to escape: I saw two soldiers go into the cage to beat him as punishment.[79]

Sok was held in Orgkas Khnom in early 2013 for six weeks. Like Asoch and Romchoang, Sok also saw a fellow detainee beaten by center staff and detainee guards after a failed escape attempt—staff whipped the man three times, forced him to crawl along stony ground, and then took him to a room where detainee guards beat him more. Despite this, Sok escaped after he and a small group of friends broke the tiles in the roof of his room at 3 a.m. one morning and then jumped the external wall. “It was too brutal in there,” he said.[80]

According to interviewees, physical abuse for minor reasons or without apparent rationale is common. Pram, who was detained in Orgkas Khnom for three-and-half months in early 2013, said, “The most difficult thing is the beatings: they happen every other day.”[81]

Detainee guards in charge of each room commonly beat each new person shortly after arrival.[82] Sokrom, a woman in her mid-40s held in Prey Speu for three months at the end of 2012, said two guards beat her for asking to go to the toilet.[83] Palkum, an adolescent child when detained in the gendarme center in Battambang for two weeks in early 2013, said he witnessed staff beating two people with a piece of firewood after the two had quarreled.[84] Champey, confined in Orgkas Khnom for three months in early 2013, said he saw the center director beat a man with a bamboo pole as punishment after the man kept vegetables from the center’s vegetable patch for himself to supplement the center’s meager meals.[85]

Former detainees told Human Rights Watch that they were beaten for committing errors while performing daily military-like exercises and drills. Buon described life in the center: “Even if an NGO visited the center, we wouldn’t be free to talk. To really explain what it’s like we have to wait until we are released.”[86] On one occasion he fell out of step during a military march and was punished. He told Human Rights Watch:

As punishment, the staff trainer told me: “Go stand in the water pit!” I stood in the pit of organic fertilizer: I had to stand an hour in filthy water mixed with urine, with snails and insects in the water. It came up above the knee. It smelt terrible and the smell stuck to me afterwards. While I was standing there I was so unhappy I wanted to die.

His punishment continued the next day.

I had to leopard crawl on the ground about 200 meters. I had cuts on my elbows and forearms and blood was flowing like water. Every step I was beaten by a detainee guard with a rubber water hose. The staff was watching. I just kept crawling forwards, trying not to care about being hit, but I was crying.[87]

Thmat is a street vendor in her late 20s who was arrested while sleeping in a market place in Phnom Penh. Despite not being a drug user, she was forced to perform military-like exercises and marches each morning. She told Human Rights Watch that she was punished when she made a small mistake while singing a marching song:

I was slapped three or four times by a female staff. Then she made me hold both hands behind my head and jump until I was exhausted. Then I had to crouch on the ground with my hands behind my head in the sun for three hours.

Thmat also told Human Rights Watch that male staff members raped her:

There were two of them who raped me. They were the staff in charge of me and other women. It was at night around 9 p.m. and they called me to their room. There was a struggle but if I refused then I got beaten. They told me not to tell anyone: they said, “If the boss knows this, we will beat you.” They did it to other women as well, to beautiful women and new arrivals.[88]

Forced Labor

Individuals are often compelled to work while being held in Cambodia’s drug detention centers. This is not government law or policy. Rather, the requirement to work differs across centers and appears to be left to the discretion of center directors. International law prohibits forced labor. Although there is an exception to this prohibition for “[a]ny work or service exacted from any person as a consequence of a conviction in a court of law” (if certain other preconditions are met), people held in drug detention centers in Cambodia have not been detained following a conviction in a court of law.[89]

In some centers, all detainees are forced to work at tasks related to the basic functioning of the center. For example, in the police-run center in Bavel district, Battambang province, Meak told Human Rights Watch that everyone held in the center had to work for one or two hours each day:

We had to dig the ground and plant vegetables, or collect firewood outside the center for the kitchen. Kids have to cut grass. It is a rule of the center to work because they want to correct us. I did not see anyone who tried not to work.[90]

Beng, in his early 20s, was detained in the police center in Siem Reap. He told Human Rights Watch:

Once every three or four days, for five hours in the morning, I worked cutting grass in front of the police commission. They told us it was to keep us busy. Four police men kept watching us all the time to stop us from escaping.[91]

In other centers, people held after being apprehended by the police must work at tasks related to the functioning of the center, while detainees whose families pay for their detention do not have to do this work. For example, Buon, who was seized by police while sleeping in the park, said:

I had to clean dishes all day. If you don’t work in the kitchen, you work in the garden. If you are arrested by the police and you don’t work at all, you are beaten up.[92]

Takiev, in his early 20s, was arrested by park guards and held in Orgkas Khnom in early 2013:

At meal times we had to prepare the tables for 320 people, then wash the dishes. This work took three hours each day. If I did not clean the dishes I was beaten. There are inspections and if there was something unclean then we all got beaten.[93]

In three centers —Orgkas Khnom, the gendarme-run center in Banteay Meanchey province, and the gendarme-run center in Battambang— individuals previously held in the centers described being forced to work in construction.

According to Chaet, a man in his early 20s who was held at the gendarme center in Banteay Meanchey for four months, those in the center were forced to construct a four-story building intended to increase the center’s capacity to detain more people. He said:

All the detainees are used to construct a new building in the gendarme compound. It has four floors. There is space in each room for many people and there are bars in the windows. That means more people can be held there.[94]

In May 2013, a Human Rights Watch researcher witnessed dozens of detainees working in the center in Banteay Meanchey province. They were carrying sand from near the front of the gendarme compound towards a new four-story building covered in scaffolding, also inside the compound. They were working under the immediate supervision of a detainee guard carrying a stick.

Former detainees from two centers described work teams whose members labored outside the centers. Champey, in his mid-20s, told Human Rights Watch that during his three-month stay in Orgkas Khnom he was forced to work on the property of the then-director of that center. He said:

I worked at the house of the center’s director: I laid tiles and curbing on his property. His house is near Orgkas Khnom. I did this for about two weeks. There were three guards at the house while we worked there: they were watching us all the time, afraid we would run away. If I hadn’t worked there the detainee guards would have beaten me up. The director said, “As soon as you finish the work you can leave the center.”

Champey said that he was released a few days early because of the work.[95]

Another detainee, Takiev, told Human Rights Watch that he was also forced to perform manual labor at the house of the then-director of the Orgkas Khnom center. He said:

Every day at six o’clock in the morning they drove us in a truck belonging to the center director and we returned to the center at five o’clock in the evening. The house of the boss of the center is close to Orgkas Khnom— it’s a big villa made of stone. Eleven of us worked digging pits and laying drainage pipes in the ground. It was very tiring to work in the sun.

When asked why he performed this work, Takiev said:

The rule is to stay in Orgkas Khnom for three months but if you work like this, you get released sooner. I was released early because I worked hard and quickly while digging the ground. They told me: “If you don’t work you’ll be beaten up and sent back to the center and not allowed to go home.”[96]

Other people formerly held in Orgkas Khnom confirmed that they saw fellow detainees leave the center during the day to work at the house of the then-director of the center.[97]

Former detainees at the gendarme-run center in Battambang told Human Rights Watch that detainees worked on the construction site of a new hotel in Battambang. Palkum said:

In the early morning detainees were driven in a Nissan pickup truck to work at the hotel. They came back covered in cement. After I was released I went near the hotel and I saw them working there. About 20 detainees were inside and four of my friends were with them. They were doing stone work, laying the floor, that sort of thing.[98]

Pisak, in his mid-20s, spent six weeks in the gendarme center in Battambang in mid-2012. He explained that the gendarmes tell detainee guards which individuals they want to work. Detainees then work in the morning from 7 or 8 a.m. to 11 a.m., come back to the center for lunch, then return to the construction site to work from 1 p.m. to 5 p.m. before they are taken back to the center at night. Pisak described what happened to one person who tried to escape while working on the construction site and was then recaptured:

When he arrived back to the center, he had almost lost consciousness from his beating. He was then beaten a second time at the center by both the gendarme and the detainee guards. The gendarme said to us: “You guys watch this: if you dare to run away, you will get the same!” His backside had no skin left after the beating.[99]

Others held in the Battambang center confirmed that they saw detainees leave each day to work at the hotel construction site.[100]

In mid-May 2013, a Human Rights Watch researcher saw young men working at the construction site of a large hotel in Battambang. Gendarmes were watching them work. A pickup truck with gendarme license plates and loaded with the young men then drove from the construction site in the direction of the gendarme center in Battambang town. However, the destination of the pickup could not be confirmed.

Young men who had been working under gendarme supervision on the construction site of a hotel in Battambang are driven in a pickup towards the gendarme-run drug detention center. © 2013 Human Rights Watch

III. International Legal Standards

Right to Health

The right to the highest attainable standard of health includes the principle of treatment following informed consent. The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), which Cambodia has ratified, addresses the right to health in article 12.[101] The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the international expert body that provides authoritative interpretations of the ICESCR, has stated in its General Comment on the right to health that it includes “the right to be free from ... non-consensual medical treatment and experimentation.”[102] The World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) also note that:

The same standards of ethical treatment should apply to the treatment of drug dependence as other health care conditions. These include the right to autonomy, and self determination on the part of the patient, and the obligation for beneficence and non maleficence [do good/do no harm] on behalf of treating staff.[103]

It is Human Rights Watch’s view that no one should be detained solely because of drug dependency. Compulsory treatment for people dependent on drugs can only be legally justified in exceptional circumstances of a crisis situation if the treatment provided is scientifically and medically appropriate and of good quality, and where such an intervention is intended to return a person to a state of autonomy over their own treatment decisions. Such interventions should be strictly time-bound, of short duration, and subject to review by an independent authority. Absent such conditions, there is no justification for compulsory treatment.

WHO and UNODC note that “neither detention nor forced labor have been recognized by science as treatment for drug use disorders.”[104]

Arbitrary Arrest and Detention

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), to which Cambodia is a party, states that, “No one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest or detention.”[105] According to the UN Human Rights Committee, detention is considered arbitrary if it is not in accordance with law or if it presents “elements of inappropriateness, injustice, lack of predictability and due process of law.”[106] The ICCPR recognizes the right of detainees to be informed of the reasons for their arrest and of any charges against them, as well the rights to have legal assistance and to challenge the lawfulness of the detention before an appropriate judicial authority.[107]

Torture and Ill-Treatment in Custody

Cambodia has a legal obligation to investigate credible allegations of torture and cruel and inhuman treatment or punishment. The Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, ratified by Cambodia, contains an absolute prohibition on the use of torture and other ill-treatment.[108] Rape and other forms of sexual assault in detention may amount to torture.[109]

Governments are obligated to “proceed to a prompt and impartial investigation, wherever there is reasonable ground to believe that an act of torture has been committed” even where a victim does not initiate the complaint.[110] Credible reports of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment by, or at the instigation of, a public official must also be promptly and impartially investigated.[111]

WHO and UNODC state that “[i]nhumane and degrading practices and punishment should never be part of treatment of drug dependence.”[112]

Detention of Children

The Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), to which Cambodia is also a party, defines a child as any person under the age of 18. The CRC obligates governments to protect children from “all forms of physical or mental violence, injury or abuse, neglect or negligent treatment, maltreatment or exploitation, including sexual abuse, while in the care of parent(s), legal guardian(s) or any other person who has the care of the child.”[113] The CRC also states that any arrest, detention, or imprisonment of a child must conform with the law and can be done only as a “measure of last resort.”[114] The detention of children in the same facilities as adults is prohibited.[115]

Detention of Persons with Disabilities

Cambodia ratified the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) in December 2012.[116] The convention not only forbids arbitrary detention but also states that “the existence of a disability shall in no case justify a deprivation of liberty.”[117] It also provides that people with disabilities have the right to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health, including on the basis of free and informed consent.[118]

The CRPD prohibits subjecting any person to torture or to cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment, including non-consensual medical or scientific experimentation.[119] It also requires Cambodia to “take all appropriate legislative, administrative, social, educational and other measures to protect persons with disabilities… from all forms of exploitation, violence and abuse.”[120]

Forced Labor

Cambodia has ratified International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention No. 29, which prohibits forced or compulsory labor, understood as “all work or service which is exacted from any person under the menace of any penalty and for which the said person has not offered himself voluntarily.”[121] The ban on forced labor in international law does not cover “[a]ny work or service exacted from any person as a consequence of a conviction in a court of law” if certain preconditions are met. However, people held in drug detention centers in Cambodia have not been detained due to a conviction in a court of law.

With respect to forced labor for a commercial undertaking such as building construction, ILO Convention No. 105 prohibits forced or compulsory labor as “a method of mobilising and using labour for purposes of economic development.”[122]

Acknowledgements

This report was researched and written by a senior researcher at Human Rights Watch. It was edited and reviewed by Joseph Amon, director of the Health and Human Rights Division at Human Rights Watch. Shantha Rau Barriga, director of the Disability Rights Division; Bede Sheppard, deputy director of the Children’s Rights Division; Phil Robertson, deputy director of the Asia division; a researcher in the Women’s Rights Division; James Ross, legal and policy director; and Danielle Haas, senior editor in Program, also reviewed the report. They are all with Human Rights Watch. Joao Bieber provided research support. Production assistance was provided by Grace Choi, director of publications; Kathy Mills, publications specialist; and Fitzroy Hepkins, administrative manager.

Human Rights Watch is deeply grateful to the many individuals who shared their knowledge and experiences with us. Without their testimony this report would not be possible.

Annex 1: Correspondence with the Cambodian Government

September 25, 2013

H.E. Ke Kim Yan

Chairman of National Authority for Combating Drugs

#275 Norodom Blvd.

Phnom Penh Cambodia

Via facsimile: +855-23-721 004

Via email: info@nacd.gov.kh

Your Excellency,

Human Rights Watch is an international nongovernmental organization that monitors violations of human rights by states and non-state actors in more than 90 countries around the world.

Human Rights Watch is preparing a report regarding the system of compulsory drug treatment in Cambodia. Our report explores issues of due process, the right to health, and freedom from torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

We are writing to request statistical and programmatic information about compulsory drug treatment efforts in Cambodia. Human Rights Watch is committed to producing material that is well-informed and objective. We seek this information to ensure that our report properly reflects the views, policies and practices of the Royal Government of Cambodia regarding the system of compulsory drug treatment.

We hope you or your staff will respond to the attached questions so that your views are accurately reflected in our reporting. In order for us to take your answers into account in our forthcoming report, we would appreciate a written response by October 25, 2013.

In addition to the information requested below, please include any other materials, statistics, and government actions regarding the system of compulsory drug treatment in Cambodia that you think might be relevant.

Thank you in advance for your time in addressing these urgent matters.

Sincerely,

Joseph Amon, PhD MSPH

Director

Health and Human Rights division

cc:

H.E. Sar Kheng

DeputyPrime Minister, Minister of Interior

No.275 Norodom Blvd., Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Fax/phone: +855 23 721 190

E-Mail: info@interior.gov.kh

H.E. Tea Banh, Deputy Prime Minister, Minister of National Defence

Russian Federation Street, Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Fax: +855-23 883274

E-mail: info@mond.gov.kh

H.E. Mam Bunheng

Minister of Health

No 151-153 Kampuchea Krom Blvd.

Phnom Penh

Cambodia

Fax: + 855 23 882317/+855 23 723 832

Email: webmaster@moh.gov.kh

H.E. Ith Sam Heng

Minister of Social Affairs, Veterans and Youth Rehabilitation

No 788B, Monivong Blvd.,

Phnom Penh

Cambodia

Fax: +85523 726086

Email: mosalvy@cambodia.gov.kh

H.E. Pa Socheatevong

Governor of Phnom Penh, No. 69, Preah Monivong, 12201 Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Fax: +855-23-722 054

Email:

We would appreciate any information you can provide regarding the following:

Background and statistical information

- How many government-run compulsory drug treatment centers currently operate in Cambodia? Please indicate the government authority responsible for running each center.

- Please provide data for 2012 and (separately) for 2013 – to date, indicating for each center:

- How many people were detained (please specify the number of men and women, and male and female children under age 18 years in each center)?

- How many people were detained in government-run drug treatment centers in Cambodia for other reasons?

Table 1: Individuals held for drug use:

|

Name of Center |

Location |

2012 |

2013 (to date) |

||||||

|

|

|

Men |

Women |

Male Children |

Female Children |

Men |

Women |

Male Children |

Female Children |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 2: Individuals being held for other reasons (please specify gender if available):

|

Name of Center |

Location |