The UK Border Agency has published a report today showing that targets to speed up the asylum procedure are unachievable. The chief inspector, John Vine, said that the agency deals with vulnerable people and "we should remember that, first and foremost, this is about people's lives".

But how do hundreds of women, including vulnerable ones with complex cases, end up in a Kafkaesque procedure known as the detained fast track (DFT) which is designed for straightforward cases with a quick resolution?

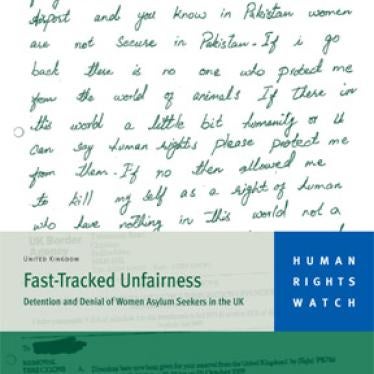

That's the question posed in a new report by Human Rights Watch published this week, Fast-Tracked Unfairness: Detention and Denial of Women Asylum Seekers in the UK.

Our research has shown that women with complex asylum claims - often based on family violence, rape or trafficking - are now being shunted through this fast-track system, even though their cases are inherently not capable of quick resolution.

Women such as Fatima H from Pakistan, who says her locally powerful husband, a man with close links to the police, subjected her to a sustained regime of domestic violence from which she had no way of escaping locally. Or Xiuxiu L from China, who says she was trafficked into the UK after being held as a sex slave for five years. Or Aabida M from Algeria, who said her affair outside of marriage led to threats from her family to kill her.

Once a woman is in the DFT system the odds are stacked against her. She is taken to Yarl's Wood and one or two days later interviewed for asylum. If refused - and in 2008 (the most recent full year figures available) 96% of claims were refused at first instance - she has two days in which to appeal. The appeal is then heard within 11 days. From start to finish the whole process takes two weeks. This gives insufficient time to assemble evidence or get expert opinions to support a claim. In 2008, 91% of appeals were rejected.

The Home Office claims that the statistics show that the system is working. Around a quarter of cases put into DFT are removed from it before the initial decision. Officials say that only cases capable of quick resolution pass through DFT. But solicitors and NGOs that provide legal representation say that re-routing back to the standard asylum system is usually due to quick intervention on their part and that many complex cases remain in DFT.

Human Rights Watch did not set out to assess whether Fatima, Xiuxiu, Aabida (not their real names) and other women in DFT should be granted asylum. We consider only whether their claims should have been put into the DFT procedure in the first place - and whether DFT gives them a decent chance to make their case. What many of these women have in common is that their claims are inherently complicated, involving their own states' failure to protect them from gender-based violence and abuse. Organisations that provide services to refugee women estimate that more than half of all women seeking asylum in the UK are survivors of sexual violence.

That the trauma of rape can inhibit women from seeking help is recognised by the UK's courts - but an asylum-seeker is expected to open up immediately to total strangers about her experiences. If she delays it may be too late. And she has to do this while in detention, quite probably to a legal representative she has only spoken to briefly over the phone and a case officer she might view as hostile. Cases like this cannot be processed at breakneck speed. The UKBA has guidelines about complex gender-related cases - but these appear to be applied inconsistently.

None of this should be news to the UKBA and the Home Office. In August 2006 the Home Office's own asylum quality team reported that the referral mechanism to DFT was not "sufficiently robust or substantive enough to properly identify complex gender-related claims".

In March 2008 UNHCR told the Home Office that DFT decisions often "fail to engage with the merits of the claim" and expressed concern about the speed of the process. In May 2009 the House of Commons home affairs committee said the government's aims of deterring fraudulent applications may disadvantage the often severely traumatised victims of trafficking.

By the end of 2011 UKBA aims to conclude 90% of new asylum cases within six months of application. But it is neither reasonable nor in accordance with the UK's obligations under international refugee law to seek to achieve this target by dint of using an inherently unfair procedure. The correct test of an asylum system is that those in need of protection receive it, not the speed with which they are rejected.