Eighty years ago, the firebombings of Dresden and Tokyo demonstrated the horrors of incendiary weapons. These UK and US airstrikes near the end of the Second World War blanketed large cities with weapons, including napalm bombs, containing chemical compounds that ignite to set fires and burn people. The heat, flames, and smoke killed approximately 25,000 people in Dresden and left civilian structures and major cultural landmarks in ruins. The conflagrations in Tokyo killed 100,000 people and wiped out the city’s wooden homes.[1]

Survivors described the terror and pain that they experienced on the ground. Witnesses to the Tokyo attack, for example, remembered seeing family members go up in flames, stepping over scorched bodies, and smelling flesh burn.[2] One of the US airmen who dropped the incendiary bombs said that the “fire in Tokyo must have ranked as one of the most horrendous fires in the history of mankind.”[3]

Because of the outrage generated by these attacks and changes to international humanitarian law, large-scale airstrikes with incendiary weapons have not occurred in recent years. They are expressly prohibited by the 1980 Protocol III to the Convention on Conventional Weapons (CCW), which is the only international legal instrument dedicated to incendiary weapons.

Nevertheless, 45 years after its adoption, Protocol III has not adequately addressed the humanitarian consequences of incendiary weapons. The use of such weapons continues to cause excruciating burns and lifelong harm to civilians and combatants alike. It also destroys homes, shops, schools, and crops.

Despite widespread support among states for discussing these impacts and possible solutions, the consensus decision-making process of CCW meetings has created a roadblock to progress. It is time for states to consider different forums in which to discuss this issue and to create standards that strengthen humanitarian protections from incendiary weapons.

Recommendations

To better protect civilians from incendiary weapons, governments should:

- Work to create stronger international standards that close loopholes in existing international law and that further stigmatize the use of incendiary weapons. A complete ban on incendiary weapons would have the greatest humanitarian benefits;

- Consider the issue of incendiary weapons at the United Nations General Assembly’s First Committee on Disarmament and International Security, a forum that is inclusive and not bound by consensus decision-making, as well as at CCW meetings;

- Call for and convene dedicated discussions of the humanitarian concerns raised by these weapons and the inadequacy of applicable international law;

- Raise awareness of the human cost of incendiary weapons and the need to improve international protections for civilians; and

- Condemn the use of incendiary weapons due to the gravity of their humanitarian consequences.

The Human Cost of Incendiary Weapons

Incendiary weapons are notorious for their horrific human cost. Weapons with incendiary effects, including white phosphorus munitions, produce similarly cruel injuries despite, as discussed below, falling outside the definition of incendiary weapons under Protocol III to the Convention on Conventional Weapons.

Immediate Effects

Immediately after use, incendiary weapons cause:

- Extensive and excruciating burns that require painful treatment. White phosphorus inflicts particularly deep burns and can reignite when bandages are removed;

- Respiratory damage from inflamed airways and toxic fumes;

- Infection, extreme dehydration, and organ failure; and

- Psychological trauma from injuries and treatment.

Long-Term Physical Harm

Those who survive initial injuries face long-term physical harm, including:

- Intense, chronic pain;

- Severe scarring and loss of mobility;

- Dead nerve endings and temperature hypersensitivity;

- Brain damage from shock or hypoxia;

- Restricted growth in children; and

- Need for lifelong physical treatment.

Long-Term Psychological Harm

Ongoing psychological harm includes:

- Post-traumatic stress (PTSD), anxiety, and depression; and

- Need for lifelong mental health support.

Challenges to Treatment

Caring for the victims and survivors of incendiary weapons presents numerous challenges, including:

- Difficulty of treating burn injuries, which is exacerbated in armed conflict;

- Inadequate specialized supplies and equipment;

- Shortage of medical and burn experts;

- Lack of knowledge about how to treat incendiary weapon injuries;

- Few professional ambulances for transfers to better facilities;

- Gaps in continuity of long-term care;

- Deprioritization of or limited resources for mental health support; and

- Trauma to medical personnel.

Other Long-Term Harm

Socioeconomic and other types of harm include:

- Detachment from society due to scarring or disabilities;

- Inability to work or attend school;

- Loss of crops and damage to agricultural land;

- Displacement; and

- Damage to the environment and local ecosystems.

Use of Incenidary Weapons

Over the past 15 years, Human Rights Watch has documented the use of a variety of incendiary weapons, including weapons with incendiary effects, in Afghanistan, Gaza, Iraq, Lebanon, South Sudan, Syria, Ukraine, and Yemen. In 2023-2024, for example, researchers found evidence of the use of air-dropped and ground-launched incendiary weapons in Syria and Ukraine as well as white phosphorus in Gaza and Lebanon. Over the past year, researchers verified use in South Sudan and Ukraine, some of which involved new kinds of improvised incendiary weapons employing starkly different levels of technology.

In March 2025, South Sudan’s air force used improvised incendiary weapons in at least four attacks in Upper Nile state. The weapons consisted of barrels with flammable substances dropped from aircraft. The attacks killed at least 58 people, including children, and severely burned others.[5]

Witnesses told Human Rights Watch they saw the bodies of charred neighbors and people with burned teeth or blistered skin. Villages went up in flames, destroying dozens of homes, shops, and other civilian structures. Health workers struggled to treat the wounded due to limited resources. First responders told Human Rights Watch that the fires burned for several days until rain extinguished them.

In Ukraine, Human Rights Watch documented Russia’s use of quadcopter drones—which are small, short-range, maneuverable, and relatively inexpensive—to deliver incendiary weapons onto targets in the city of Kherson in southern Ukraine near Russian-occupied territory.

In one case, Human Rights Watch verified a November 18, 2024, drone video, uploaded to a Russian military-affiliated Telegram channel, of an attack with incendiary weapons at the Kherson Regional Oncology Center. A drone dropped two improvised incendiary weapons on two vehicles on the grounds of the hospital, which were then engulfed in flames. A photograph of the vehicles’ burned shells, published by the Kherson Prosecutor’s Office the same day, revealed they were ambulances.

Human Rights Watch also verified a November 20, 2024, drone video from a Russian military-affiliated Telegram channel that shows a drone hovering above a store before dropping a small bottle-shaped munition through a hole in the roof, causing a fire inside. While Human Rights Watch could not identify the specific munition, it appeared to be an improvised incendiary weapon comprised of a flammable liquid dispersed and ignited by a small explosive charge.

Human Rights Watch analyzed an additional five videos that appear to show the use of incendiary weapons launched by either rocket artillery or “Dragon Drones” across several regions of Ukraine between September 2024 and January 2025. Dragon Drones spread liquid incendiary compounds over a wide area on the ground below.

Existing International Law and Its Shortcomings

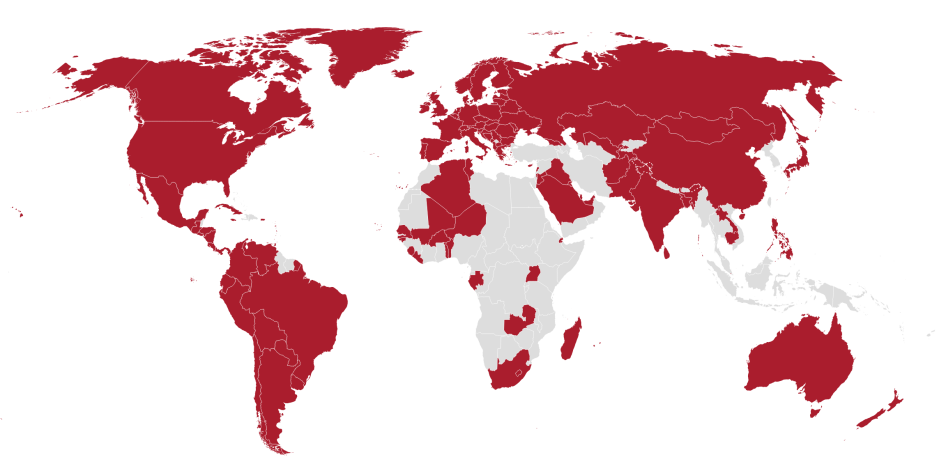

Protocol III to the Convention on Conventional Weapons is the only international law dedicated to incendiary weapons. As of October 2025, 117 countries had joined the 1980 protocol.

Protocol III prohibits the firebombing of cities, like the attacks on Dresden and Tokyo, but it has failed to adequately protect civilians from the full range of incendiary weapons, including weapons with incendiary effects. The problem goes beyond a need to attract new states parties and improve implementation. The protocol also has two loopholes that have undermined its effectiveness:

- First, by describing incendiary weapons as those “primarily designed” to set fires or burn humans, Protocol III’s definition of incendiary weapons excludes most multipurpose incendiary munitions. The definition does not encompass munitions, such as white phosphorus, that are “primarily designed” to create smokescreens or signal troops yet have the same cruel incendiary effects.

- Second, Protocol III prohibits the use of air-dropped incendiary weapons in concentrations of civilians, but the provision on ground-launched incendiary weapons includes several caveats that weaken it. This arbitrary distinction ignores the fact that incendiary weapons cause horrific burns and destructive fires regardless of their delivery mechanism.

Addressing these shortcomings will require new, more comprehensive standards. Whatever form such standards take, they should focus on the weapons’ incendiary effects rather than their design or delivery mechanisms.

State Concerns and Calls for Action

Most of the international debate surrounding incendiary weapons to date has taken place during annual meetings of CCW high contracting parties. Since 2010, states have expressed widespread outrage at the humanitarian impacts of incendiary weapons, and strong support for action, but no concrete steps have taken place due to the body’s reliance on consensus for decision-making.

Concern and Condemnation

At the November 2024 meeting, numerous high contracting parties voiced concern about and condemned the use of incendiary weapons in statements and working papers.[4]

A working paper jointly submitted by 10 states—Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Costa Rica, Ireland, Mexico, New Zealand, Norway, the Philippines, and Switzerland—described incendiary weapons as “among the most inhumane in warfare.” They elaborated on the horrific physical, mental, and socioeconomic impacts of incendiary weapons and emphasized the importance of also addressing weapons with incendiary effects (e.g., white phosphorus). Germany, Luxembourg, Ukraine, the European Union (EU), the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), and civil society echoed these sentiments.

Ireland, Palestine, the Arab Group, and the Organization of Islamic Cooperation explicitly voiced concern about or denounced the use of white phosphorus in Gaza and Lebanon over the previous year. Costa Rica expressed its concern about use in “current conflicts.”

Dedicated Discussions

Recognizing the unacceptable humanitarian consequences of incendiary weapons, many delegates at the 2024 CCW meeting called for dedicated time to address incendiary weapons and Protocol III. Canada, Japan, the UK, the EU, the ICRC, Article 36, and Human Rights Watch supported this position. In addition, the 10 states that submitted the joint working paper specifically proposed holding informal consultations in the CCW intersessional period, followed by discussions at the 2025 annual meeting.

As it has since the last CCW Review Conference in 2021, however, Russia blocked the proposal as well as the inclusion of language on incendiary weapons in the final report of the meeting.

Next Steps

Given the limited progress under the auspices of CCW, states should examine the consequences of incendiary weapons and the limits of international law in a different forum. The UN General Assembly’s First Committee could advance work on this topic because the General Assembly is open to all states, is unconstrained by consensus-decision making, and has a broader mandate than the CCW. Independent experts meetings could also serve as useful forums for considering incendiary weapons.

Such discussions need not end work at the CCW. CCW high contracting parties should continue to raise concerns about the human costs of incendiary weapons and push for action on Protocol III.

Statements Addressing Concerns on Incendiary Weapons at 2021-2024 CCW Meetings

This table reflects positions explicitly articulated by CCW High Contracting Parties since their last Review Conference in 2021 based on written statements, working papers, and UN transcripts and audio files of the meetings, all posted online, as well as on Human Rights Watch notes.

| Condemned or expressed concern about use | Supported informal consultations during the intersessional period | Supported further discussion, including through a separate agenda item | Called for amending or strengthening Protocol III | |

| Argentina | X | X | ||

| Australia | X | X | X | |

| Austria | X | X | X | X |

| Belgium | X | X | X | |

| Brazil | X | X | X | |

| Canada | X | |||

| Chile | X | X | X | X |

| Colombia | X | X | X | |

| Costa Rica | X | X | X | X |

| Ecuador | X | X | ||

| Germany | X | X | X | |

| Holy See | X | X | X | |

| Ireland | X | X | X | |

| Japan | X | |||

| Kazakhstan | X | |||

| Luxembourg | X | X | ||

| Mexico | X | X | X | X |

| Netherlands | X | X | X | |

| New Zealand | X | X | X | |

| Norway | X | X | X | |

| Palestine | X | X | X | X |

| Panama | X | X | X | X |

| Peru | X | X | ||

| Philippines | X | X | X | X |

| Spain | X | |||

| Switzerland | X | X | X | |

| Tunisia | X | |||

| Ukraine | X | X | ||

| United Kingdom | X | X | X | |

| Uruguay | X | |||

| Arab Group | X | |||

| European Union | X | X | ||

| Non-Aligned Movement | X | |||

| Organization of Islamic Cooperation | X | |||

| ICRC | X | X | X | |

| Civil Society Groups | X | X | X | X |

State Positions in 2024

The quotations below are excerpts from working papers submitted to the 2024 Meeting of High Contracting Parties (cited in parentheses below) that reflect the concerns of states and regional groups about the use of incendiary weapons and calls for discussion of the issue.

Condemnation or Concern over Use

Incendiary weapons are among the most inhumane in warfare. They can inflict excruciating burns and respiratory damage, for which specialized medical attention is generally unavailable in areas of armed conflict. The use of incendiary weapons can also cause profound psychological trauma. The burning of homes, infrastructure, and crops results in long-lasting socioeconomic harm and creates long-lasting legacy suffering.

(CCW/MSP/2024/WP.5/Rev.1)

Costa Rica also joins the concerns raised by other delegations regarding the increasing use of incendiary weapons, including white phosphorus, in current conflicts.

(CCW/MSP/2024/WP.25, translated by Human Rights Watch)

The Arab Group … condemns the use of white phosphorus by the occupying power in its attacks against Gaza and Lebanon, resulting in civilian casualties, destruction of civilian objects, and widespread fires in agricultural lands and forests, causing long-term environmental damage.

(CCW/MSP/2024/WP.24)

The illegal occupying forces have also used incendiary weapons (white phosphorus) in Gaza, resulting in injuries to civilians, destruction of civilian objects, and burning vast areas of agricultural land and forests, causing long-term environmental damage.

(CCW/MSP/2024/WP.8)

Since the beginning of its aggression, the Russian Federation has deployed a range of weapons that are explicitly restricted or prohibited under CCW and international humanitarian law. These include indiscriminately used landmines, improvised explosive devices (IEDs), booby traps, and incendiary weapons—all of which have inflicted immense suffering on Ukrainian civilians and contaminated vast areas of our land.

(CCW/MSP/2024/WP.16)

The EU remains concerned about and condemns the use of incendiary weapons against civilians or against targets located within a concentration of civilians, their indiscriminate use causing cruel effects and unacceptable suffering.

(CCW/MSP/2024/WP.6/Rev.1)

Organization of Islamic Cooperation

The High Contracting Parties must also strongly denounce the use of white phosphorus by Israel, the illegal occupying power, in areas of high concentration of civilians in illegally occupied Gaza and Lebanon. The targeted use of white phosphorus in such areas with the result and primary design of causing burn injuries to persons makes it an incendiary weapon for the purposes of Protocol III.

(CCW/MSP/2024/WP.14)

Calls for Dedicated Discussions of Incendiary Weapons

These discussions could, for example, consider whether greater clarity could be achieved with regard to the scope of Protocol III and of weapons with combined effects, which include incendiary effects…. This should be an open exchange on the Protocol, its implementation and how it fulfils its role in addressing the humanitarian harm caused by the use of incendiary weapons.

(CCW/MSP/2024/WP.5/Rev.1)

Costa Rica also joins the concerns raised by other delegations regarding … the absence of an item on the agenda of this conference dedicated to the review of Protocol III.

(CCW/MSP/2024/WP.25, translated by Human Rights Watch)

Due to [incendiary weapons’] excessively harmful and indiscriminate effects, Luxembourg reiterates the importance of Protocol III, which prohibits the use of incendiary weapons. We call on all States to ratify this Protocol and implement its provisions, particularly the prohibition of their use in densely populated areas. We deplore the removal of discussions on Protocol III from the agenda.

(CCW/MSP/2024/WP.34, translated by Human Rights Watch)

The UK continues to regret that Protocol III issues remain absent from the CCW agenda because of the opposition of a single High Contracting Party and echo others’ calls to conduct informal consultations on Protocol III during the intersessional period, and for a specific item on Protocol III to feature on the agenda for our meeting next year.

(CCW/MSP/2024/WP.4)

We regret that Protocol III issues were removed from the CCW agenda because of the opposition by Russia and we request to have them back next year, since a structured debate on the implementation of the Convention should be allowed on all of its protocols.

(CCW/MSP/2024/WP.6/Rev.1)

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Reports

- Human Rights Watch, Beyond Burning: The Ripple Effects of Incendiary Weapons and Increasing Calls for International Action, November 2020, https://www.hrw.org/report/2024/11/07/beyond-burning/ripple-effects-incendiary-weapons-and-increasing-calls

- Human Rights Watch and Harvard Law School’s International Human Rights Clinic, “Reviewing the Record: Resources on Incendiary Weapons from Human Rights Watch and the International Human Rights Clinic at Harvard Law School,” June 2024, https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/media_2024/06/IW_ReviewingtheRecord_0624.pdf

- Human Rights Watch and Harvard Law School’s International Human Rights Clinic, “They Burn through Everything”: The Human Cost of Incendiary Weapons and the Limits of International Law, November 2020, https://www.hrw.org/report/2024/11/07/beyond-burning/ripple-effects-incendiary-weapons-and-increasing-calls

- PAX, Put Out the Fire: Strengthening International Law and Divestment Policies on Incendiary Weapons, September 2021, https://paxforpeace.nl/news/put-out-the-fire-strengthening-international-law-and-divestment-policies-on-incendiary-weapons/#content

Videos

- Human Rights Watch, “Incendiary Weapons: Explainer,” March 2023, https://www.hrw.org/topic/arms/incendiary-weapons

- Human Rights Watch, “Incendiary Weapons: Human Cost Demands Stronger Law,” November 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/11/09/incendiary-weapons-human-cost-demands-stronger-law (video at top of press release)

- “Incendiary Weapons: Views from the Frontlines and the Financial Sector,” Humanitarian Disarmament, December 2021, https://humanitariandisarmament.org/2021/12/14/incendiary-weapons-views-from-the-frontlines-and-the-financial-sector/ (event summary with speaker videos)

For more information, please contact Bonnie Docherty, docherb@hrw.org or bdocherty@law.harvard.edu.

[1] Sinclar McKay, Dresden: The Fire and the Darkness (UK: Penguin Books, 2020), p. xxii; James M. Scott, Black Snow: Curtis LeMay, the Firebombing of Tokyo, and the Road to the Atomic Bomb (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2022), p. 250.

[2] Scott, Black Snow.

[3] Ibid., p. 111.

[4] While the 2024 CCW meeting became an informal session, many states and organizations submitted public working papers and/or statements. For working papers and statements from the 2024 CCW Meeting of High Contracting Parties, see UN Office of Disarmament Affairs, Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons: Meeting of High Contracting Parties, 2024, https://meetings.unoda.org/meeting/70961/documents?f%5B0%5D=document_type_documents%3AWorking%20papers. See also Reaching Critical Will’s webpages from that meeting: https://reachingcriticalwill.org/disarmament-fora/ccw/2024/hcp/documents and https://reachingcriticalwill.org/disarmament-fora/ccw/2024/hcp/statements (all accessed October 3, 2025). For analysis of the meeting, see Reaching Critical Will, CCW Report, vol. 12, no. 4, November 21, 2024, https://reachingcriticalwill.org/disarmament-fora/ccw/2024/hcp/ccw-report (accessed October 3, 2025).