Table of Contents

- Summary

- Methodology

- Indications of Recent Acquisitions

Equipment Found in Use by Each Side

a. RSF

b. SAF

Possible Violations of the UN Arms Embargo on Darfur

a. Alleged UAE support to the RSF in violation of the Darfur arms embargo

- Foreign-Made Drone Attacks against Apparent Unarmed Civilians by SAF-Affiliated Fighters in Khartoum

a. SAF and RSF

i. Drones, identifiable as DJI Matrice models, commercially manufactured for civilian use

ii. Drone Jammers

iii. 9M133M Kornet anti-tank guided missile

b. RSF

i. Unidentified Attack VTOL Drone equipped with Yugoimport 120mm Thermobaric Munitions

ii. Unidentified Truck-Mounted Multi-barrel Rocket Launcher

iii. One-Way Attack Drone

iv. Type PP87 Mortar Munitions

c. SAF

a. To the United Nations Security Council

b. To United Nations Member States, including Particularly Concerned Regional States

c. To Sudan’s Neighboring Countries, including Chad, Egypt, South Sudan, Ethiopia

Summary

Since the conflict between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) began in Sudan in April 2023, countless civilians have been killed, millions have been internally displaced, and millions face famine.

There is a large and growing body of credible evidence documenting how, during their conduct in the conflict, the warring parties have committed widespread war crimes, crimes against humanity, and serious human rights violations, including in the Darfur region. For example, Human Rights Watch, among others, has documented devastating ethnic cleansing in West Darfur. Given the prevalence of such atrocities in the conflict, Human Rights Watch has called for the renewal and expansion of the existing arms embargo on Darfur to the rest of Sudan to prevent warring parties acquiring weapons or equipment likely to be used to perpetuate serious violations of international human rights and humanitarian law, harming civilians.

Against this backdrop, photographs and videos taken by fighters and civilians and posted on social media indicate that the warring parties have access to, and are using, modern, foreign-made weapons and equipment. The emergence of visuals of equipment that Sudanese actors were not previously known to have, or that began to be used more frequently months after the outbreak of the conflict, suggests that the warring parties acquired some of these weapons after April 2023. In one case, lot number markings—alphanumeric codes assigned to a specific manufacturing batch—clearly indicate that the ammunition was manufactured in 2023.

Human Rights Watch research indicates that some of this equipment is being used in the Darfur region, despite the arms embargo established by the United Nations Security Council since 2004.[1]

Human Rights Watch documented the use of other apparently newly acquired foreign-made equipment—including armed drones, truck-mounted multi-barrel rocket launchers, drone jammers, and anti-tank guided missiles—in regions of Sudan beyond Darfur, such as Kordofan and the Khartoum area. Human Rights Watch also found clear incidents involving such equipment being used in apparent unlawful attacks: using drones, in at least two incidents, SAF-affiliated fighters killed and injured unarmed people in civilian clothes in the Khartoum area in January and March 2024. These findings highlight the inadequacy of an arms embargo exclusively focused on Darfur, not Sudan as a whole.

Further investigations are needed to determine definitively how the warring parties in Sudan acquired the weapons and other equipment identified by Human Rights Watch, and when exactly these acquisitions took place.

The renewal of the Darfur arms embargo and its expansion to the rest of Sudan would secure the mechanisms necessary to conduct such investigations, hold violators to account, and prevent further acquisition of equipment that would likely be used to unlawfully harm civilians and perpetuate war crimes. At a minimum, the Council should maintain the existing Sudan sanctions regime which, despite its limitations, provides the UN and Council members with in-depth reporting on the conflict in Sudan and identifies alleged violations of the embargo. The Council should also sanction those individuals and entities that have been violating the existing arms embargo on Darfur.

Methodology

This report is based on the analysis of photographs and videos posted on social media platforms and the examination of satellite imagery, in addition to other secondary sources. Human Rights Watch analyzed 49 photographs and videos showing weapons and equipment used or captured since the conflict in Sudan began in April 2023. The images were posted on Facebook, Telegram, TikTok and X, and in most cases appear to have been taken by fighters themselves.

For most of the videos and photographs, Human Rights Watch was unable to identify those who initially posted the content. In some instances, we relied on social media accounts run by Sudanese citizens or observers of the conflict, such as open source researchers and weapons specialists who reposted images they found or obtained from other platforms or social media accounts.

None of the images analyzed appear to have been online prior to April 2023. Where possible, researchers identified where and when exactly the photographs and videos were recorded, by comparing landmarks in the visuals with satellite imagery or other visuals. In other cases this was not possible, but Human Rights Watch nevertheless believes that the photograph or video was taken in the context of the current Sudan conflict; this determination is based on our analysis of the source that posted the image, the lack of prior instance of that image, and the content (including the events depicted in the image, the features of the built and natural landscape, and the features of the individuals seen or heard in the video, such as their language, accent, or clothing).

Human Rights Watch identified weapons and equipment based on their visual characteristics and compared these findings with information from several international technical reference publications and databases, including marketing materials distributed by manufacturers.

Human Rights Watch was unable to establish precisely how and when the equipment was acquired, including whether it was acquired by the particular warring party through battlefield capture from the opposing fighters, or whether it was purchased from, or provided by, other states or by private entities. Human Rights Watch was also unable to determine definitively whether the warring parties acquired any of the weapons or equipment prior to April 2023.

For this research, Human Rights Watch also reviewed public and non-public documentation, including the archived reports from the UN Panel of Experts on the Sudan, research published by Amnesty International, and news reports by the New York Times, Reuters, Bloomberg, and the BBC. Human Rights Watch also met with diplomats from nine countries that have seats on the UN Security Council at time of publication, with representatives of international institutions with knowledge of the events in Sudan, and with arms experts.

Indications of Recent Acquisitions

This report focuses on equipment and weapons that Human Rights Watch believes was likely recently acquired from foreign sources by the warring parties. This includes equipment that Sudanese actors were not known to possess before the conflict and for which visual evidence emerged months into the conflict, as well as equipment that began to be used more frequently in the months after the war broke out, and, in one case, equipment whose lot number clearly indicates it was manufactured in 2023.

Sudan has a domestic arms industry and imports a diverse range of weapons and equipment. According to the Arms Trade Database maintained by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), Sudan received weapons and equipment from Belarus, China, Iran, Russia, Ukraine, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) between 2004 and 2023. According to a 2022 assessment of Sudan’s capabilities by the International Institute of Strategic Studies (IISS), “By regional standards, Sudan’s armed forces are relatively well equipped, with significant holdings of both ageing and modern systems.”[2] The UN Panel of Experts on the Sudan has also reported since 2005 on weapons and equipment holdings by government forces and armed groups in Sudan.[3] Both the SAF and the RSF possessed foreign-made equipment when the conflict started in April 2023.

Human Rights Watch relied on the above information about the types of weapons stockpiled and acquired by Sudanese forces and armed groups in the years preceding the conflict, as well on a 2019 list of equipment produced by the SAF-owned Military Industry Corporation, as a baseline to identify the types of weapons and equipment Human Rights Watch believes to have been acquired since April 2023, including different types of drones, truck-mounted multi-barrel rocket launchers, drone jammers, and anti-tank guided missiles.[4]

The new equipment that Human Rights Watch identified was produced by companies registered in China, Iran, Russia, Serbia, and the United Arab Emirates. There is no evidence that any of this equipment was manufactured in Sudan, though some, such as the large Mohajer-6 drones, may have been assembled in the country.

In one case, Human Rights Watch found clear evidence of a recent supply of military equipment. One video posted to X on June 6, 2024, shows two men, one of whom wears a camouflage uniform typical of the RSF, unpacking and fuzing (that is, installing the trigger mechanism on) Chinese-made 82mm mortar shells, in packaging indicating they were manufactured in 2023.[5] It is unclear if the RSF acquired these shells from abroad or captured them from the SAF. The RSF alleged in November 2023 that it had captured such munition from the SAF in Omdurman.[6]

In other cases, trends of social media posts suggest that equipment not known to be in use in Sudan began to be deployed months into the conflict. For instance, a quantitative analysis of the non-profit Mnemonic’s Sudanese Archive—a database for social media posts from and on Sudan—found that, from 2023 to 2024, there has been a yearly increase in the posting of social media content bearing the Arabic word for “drone”.[7] Human Rights Watch searches on social media and in the Sudanese Archive also found that since July 2023 there was a significant increase in the number of posts of images showing armed drones, and a wider variety of drones on display. For instance, the first video Human Rights Watch found showing a mortar munition being dropped by a drone in Sudan was posted in July 2023. In January 2024, the first photographs of the wreckage of an Iranian Mohajer-6 used by the SAF appeared online and in May 2024, the SAF Facebook account shared the first videos of apparent strikes by this drone (satellite analysis suggests one of the strikes occurred between July 16, 2023, and November 26, 2023). In April 2024, photographs appeared online showing one-way attack drones—a type of drone which detonates when it hits its target—reportedly used by the RSF.

In West Darfur, witness accounts and social media posts gathered by Human Rights Watch found no instance of the use of drones during the conflict in El Geneina from April to June 2023, but in November 2023 Human Rights Watch confirmed through witness interviews and social media posts that RSF forces had deployed drones in El Geneina’s suburb of Ardamata.[8]

Equipment Found in Use by Each Side

RSF

Human Rights Watch found posts that indicate the RSF has been using 9M133M Kornet anti-tank guided missiles, an unidentified type of attack drone which drops Serbian-made Yugoimport 120mm thermobaric munitions, one-way attack drones (which detonate when hitting a target), commercially made drones normally available to civilians but retrofitted to drop mortar munitions, Chinese-made mortar munition manufactured in 2023, and Chinese-made drone jammers.

Photographs and videos Human Rights Watch reviewed show crates of the Yugoimport munitions with markings indicating they were manufactured in 2020 and initially acquired by the UAE armed forces in the context of a contract with Adasi, a subsidiary of UAE-based weapons manufacturer Edge Group that specializes in drone technology.[9] This suggests potential contemporary supply of weapons from the UAE to the RSF. Such support was reported by the UN Panel of Experts on the Sudan and the international media.[10] However, additional investigation on the chain of custody of the equipment would be required to establish when and how the deliveries were made.

The attack drone model used to drop these thermobaric munitions is of a standardized design, with a distinctive casing, but bears no markings and its maker is unknown. There is no evidence of this model of drone appearing in Sudan prior to April 2023; the first social media post Human Rights Watch found documenting its apparent use in Sudan is marked as June 2, 2023.

This drone model was, however, apparently used by the Ethiopian government during the conflict in Ethiopia in 2021, as well as by an unknown force against Houthi forces in Yemen that same year. It may be that the same source supplied the drone to all three forces, including the RSF.[11]

SAF

Content posted on social media accounts run by the Sudanese Armed Forces or its supporters shows that SAF-affiliated fighters possess and/or use Iranian-supplied Mohajer-6 attack drones, Chinese-made drone jammers, and commercially made drones normally available to civilians, modified to drop 120mm munitions.[12]

Human Rights Watch verified two videos geolocated in Bahri (Khartoum North), showing drones apparently flown by SAF-affiliated fighters dropping mortar munitions onto groups of people in civilian clothes who do not appear to be carrying weapons, killing and injuring them in strikes that may amount to war crimes (see below).

Amnesty International separately documented the acquisition of Turkish-made firearms by the Sudanese army and the acquisition of both Turkish and Russian-made firearms by arms dealers with strong links to the SAF.[13]

Possible Violations of the UN Arms Embargo on Darfur

Both the RSF and the SAF have used apparently new, foreign-made military equipment in locations in Darfur, highlighting the need for stronger monitoring and enforcement of the Darfur arms embargo and associated sanctions regime.

The Sudan sanctions regime, imposed by the UN Security Council in 2004 and extended in 2005, prohibits “the sale or supply” to all belligerents in Darfur of “arms and related materiel of all types, including weapons and ammunition, military vehicles and equipment, paramilitary equipment, and spare parts.”[14] It provides the Security Council’s sanctions committee with tools such as travel bans and asset freezes against individuals and entities violating the embargo.

The embargo has faced challenges since its creation. The UN Panel of Experts and Amnesty International have documented how Belarus, China, and Russia violated the embargo for years following its establishment. Unlike other multilateral embargoes, the Darfur arms embargo does not clearly extend to the transfer of “dual-use” equipment—items that have both civilian and military applications—which has led the Panel of Experts to point to “the need for clarification [of the regime] on the transfer and utilization of dual-use equipment.”[15] Only one individual has ever been sanctioned for violating the embargo.

In 2016, the Small Arms Survey, an NGO, found that the embargo “demonstrably failed to prevent the delivery of materiel to Darfur’s armed actors,” and said the SAF had “become the primary source of weaponry for all sides in Darfur.”[16] Focusing on small arms, Amnesty International in July 2024 reported on “large quantities” of “recently manufactured weapons and military equipment from countries such as Russia, China, Türkiye, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE)… being imported… into Sudan, and then diverted into Darfur.”[17]

Human Rights Watch identified at least seven social media posts showing three types of military or dual-use equipment in use in Darfur. At least two posts verified by Human Rights Watch show drones apparently used by the RSF in military operations in and near North Darfur’s capital El Fasher, and one shows the video feed of a SAF drone hitting pickup vehicles in El Fasher.[18] One video shows the RSF using a drone to target positions in Ardamata, West Darfur, in November 2023.[19] Two videos show RSF fighters using 9M133M Kornet anti-tank guided missiles in and near El Fasher. Finally, photographs taken in June 2023, at the time that RSF commander Ali Yacoub was killed near El Fasher, where fighting was ongoing, and their accompanying captions, indicate that he was in possession of a drone jammer.

The Kornet anti-tank guided missiles are clearly military equipment. If they were transferred to Darfur after 2004, it would be in violation of the embargo. The attack drones and the drone jammer mentioned above are technologies that did not exist when the Security Council established the UN arms embargo on Darfur in 2004, so their transfer occurred after the creation of the embargo. There is a lack of clarity as to whether the drone jammers are subject to the embargo under the sanctions regime, but they could be covered if they were used for offensive military operations, rather than simply for protective use. The drones were civilian drones, but used for military operations, in some cases retrofitted to drop munition.

Alleged UAE support to the RSF in violation of the Darfur arms embargoThe UN Panel of Experts on the Sudan, which monitors violations of the Darfur arms embargo, said in its January 2024 report that the RSF in August 2023 had started to use “several types of heavy and/or sophisticated weapons which they were not using there before,” including “Unmanned Combat Aerial Vehicles (UCAV), howitzers, multiple-rocket launchers and anti-aircraft weapons such as MANPADS, observed in [the Darfur cities of] Nyala, El Fasher and El Geneina.”[20] The Panel added that “new military supply lines” ran “through Chad, Libya, and South Sudan,” with Eastern Chad being the “the main one.” Citing sources on the ground, including in the SAF, the Panel found that the new weapons “had a massive impact on the balance of forces on the ground” in Darfur, including in the RSF takeover of West Darfur’s capital El Geneina in June and South Darfur’s capital Nyala in October 2023.[21] There have been reports since June 2023 of alleged deliveries of weapons by the United Arab Emirates to the RSF via Chad. Aviation monitors reported that from May to September 2023, over 100 cargo flights flew from the UAE, apparently to Amjarass, a remote town in northern Chad on the border with Sudan, with usually little air traffic. Many of the flights used aircraft from a small airline called Fly Sky (registered in both Kyrgyzstan and Ukraine), which the UN Security Council’s Panel of Experts on Libya found was involved in “arm (sic) trafficking air bridges,” with “efforts to disguise… activities” in support of forces allied with Khalifa Hiftar, commander of the armed group Libyan Arab Armed Forces, during multiple instances of fighting in Libya between 2014 and 2020.[22] The company at the time was involved in flights departing from the UAE, which the Panel said had a “centrally planned” air bridge in support of Hiftar’s group.[23] The Panel said the airline was in violation of the Libya sanctions regime for “flight operations for the direct, and indirect, supply of military equipment and other assistance.” The airline was also involved in dozens of cargo flights from the UAE to Ethiopia during the Tigray conflict. Fly Sky in 2021 disputed claims that it had ever operated in Libya or Libyan airspace.[24] As reports of the alleged airbridge from the UAE to Chad began to emerge, the UAE in July 2023 announced it would “build a field hospital in the Chadian city of Amdjarass to support Sudanese refugees.” The New York Times in September reported that the airport in Amjarass, Chad, had expanded “into a bustling, military-style airfield that seemed to exceed the needs of its small hospital,” and featured temporary aircraft shelters, a hangar, fuel storage bladders, an expanded compound, and an overall pattern of airfield construction comparable to the airbase previously built by the UAE at al-Khadim (also known as al-Kharouba), in eastern Libya. Two humanitarian specialists in medical emergencies confirmed to Human Rights Watch that the number of alleged flights to Amjarass far exceeded the cargo needs of a field hospital of the scale the UAE built there.[25] In its January 2024 report, the Panel of Experts on the Sudan found allegations of UAE support to the RSF to be “credible” and said that “the transfers of arms and ammunition into Darfur” that they documented “constituted violations of the arms embargo.”[26] The SAF-aligned Sudanese government publicly denounced the UAE’s alleged support to the RSF at the UN Security Council. On June 10, the Sudanese government wrote a letter to the Security Council with photographs of equipment it said had been captured from the RSF in Khartoum and Omdurman, accusing the UAE of providing the equipment. This included weapons Human Rights Watch independently identified, such as a drone jammer gun, the unidentified attack drone fitted with Yugoimport 120mm thermobaric munitions, and other types of drones. Human Rights Watch could not establish precisely how the RSF acquired this equipment. The UAE government has repeatedly denied any support to the RSF, maintaining that its presence in Amjarass is purely humanitarian, and saying that it had provided “military cooperation and assistance” “prior to the outbreak of the conflict… at the request of the Government of Sudan.”[27] |

Foreign-Made Drone Attacks against Apparent Unarmed Civilians by SAF-Affiliated Fighters in Khartoum

Human Rights Watch verified two videos showing the video feeds of drones which appear to be operated by the SAF or its allies of two incidents in which the drones drop munitions on apparently unarmed people in civilian clothes, killing and injuring them in possible violation of international humanitarian law. Human Rights Watch confirmed that both these incidents occurred in Bahri (Khartoum North), one of Khartoum’s twin cities. These incidents highlight how the parties are using new foreign-made equipment beyond Darfur to commit apparent violations of the laws of war, and how expanding the arms embargo to cover all of Sudan is important to enhance civilian protection.

One of the videos (1), posted to a pro-SAF account on March 19, 2024, shows the feed of a drone dropping a munition on people wearing civilian clothes who are loading a truck with apparent sacks of grain or flour in the busy courtyard of the Seen flour mills in Bahri, injuring or killing a man who lies motionless on the floor. No weapons or military equipment are visible near the targeted area on the video feed.

Another video (2), filmed from a drone and posted to X on January 14 by a pro-SAF account, shows the drone dropping two 120mm munitions on apparently unarmed people in civilian clothes while they cross the main street of the Halfia al-Moulouk neighborhood in Bahri. One person is killed on the spot, his body split in two, and four others lie motionless for the next two minutes until the video comes to an end. The neighborhood was under RSF control at the time. At the beginning of the video, the file name appears briefly, suggesting the video was recorded on January 13, 2024.

Weapons Identification

The following section presents key content that enabled Human Rights Watch to identify apparently newly acquired weapons and equipment being used by SAF- and RSF-affiliated fighters. This represents a small fraction of the equipment used in the Sudan conflict.[28]

SAF and RSF

Drones, identifiable as DJI Matrice models, commercially manufactured for civilian use

Country of origin: China

Users: SAF and RSF

Human Rights Watch identified five posts showing drones—or footage from them—that, from their build, markings or other specific characteristics, identify them as manufactured by DJI, a China-based commercial drone company. The drones are commercially available to civilians. These drones appear to be used by both the SAF and the RSF, including as attack drones. The drone type was used at least three times by the RSF and once by the SAF in military operations in Darfur (see above, “Potential Violations of the Sudan Sanctions Regime”).

Two photographs (1) posted on a SAF Telegram channel on July 24, 2023, show a drone clearly identifiable as a DJI Matrice series by the shape of its main body, the front-mounted sensors, the inverted propellers, and its matte grey color. The poster alleges the drone was used by the RSF in Khartoum’s sister city of Omdurman, apparently retrofitted to be able to hold an explosive munition. Two SAF soldiers show parts of the same model, saying that they downed the drone used by the RSF in Omdurman, in a video (2) allegedly filmed on November 16, 2023, and posted the same day. Human Rights Watch was unable to determine the location of the videos.

A video (3) posted by a pro-SAF account on June 9, 2024, shows members of the Joint Force— a coalition of Darfuri armed groups aligned with the SAF—around a damaged drone which they claim was used by the RSF in El Fasher, North Darfur. The drone is identifiable as a DJI Matrice series from the shape of its main body, the inverted propellers, and its matte grey color. It appears to be equipped with a mortar round. Human Rights Watch geolocated another video (4), posted by a pro-RSF account on November 3, 2023, which shows a drone filming a strike on an armored vehicle during the assault on the 15th Infantry Division in Ardamata, West Darfur. Human Rights Watch identified the drone controller shown in the video as a DJI RC Plus controller—only compatible with the DJI Matrice series—based on the screen’s position, the presence of a green ‘x’ button and of protective rubber padding around the corner of the screen, and the controller’s matte grey color.

A pro-SAF Telegram account on April 8, 2024, posted a video containing several clips of footage filmed from drones (5), watermarked with the logo of the Bara’ al-Malik Brigade, an Islamist militia aligned with the SAF.[29] In several clips, the appearance and position of the elements on the drone’s interface, such as the mini-map, the typeface, and measures such as speed and altitude, matches the interface of known DJI thermal drones. The footage shows explosions, some of which may be caused by munitions dropped from the drone, on apparent RSF positions.

In another video (6) posted by a pro-RSF account on April 1, 2024, RSF fighters point to a damaged drone, which they appear to have shot down. A mortar munition is visible next to the drone, indicating it had likely been retrofitted to become an attack drone. The drone is identifiable as a DJI Matrice series by the shape of its main body, the front-mounted sensors, the inverted propellers, and its matte grey color.

In a letter that DJI sent on September 4, 2024, in response to Human Rights Watch’s findings, DJI said that it was “not aware of any use of DJI drones by the warring parties in Sudan” and that its “longstanding policy” was “that no one should use DJI products for combat purposes.” The company added that its products are “all off-the-shelf”, that it was “unable to track customers’ end use” and that it relied “on its dealers and resellers to fulfill their obligations on discovering suspicious end use through the downstream sales.” The company said it would “investigate… the potential deviated use.”[30]

Drone Jammers

Country of origin: China

Users: SAF and RSF

There is evidence that both the SAF and the RSF have recently acquired drone jammers, which are electronic devices designed to disable unmanned aerial vehicles by interfering with their control signals.

A pro-RSF channel posted a photograph (1) showing a fighter equipped with a drone jammer with markings indicating that it was manufactured by Greetwin, a Chinese company. Another photograph (2) posted to X of equipment purported to have been found on the body of RSF commander Ali Yacoub, who was confirmed to have been killed near El Fasher in June 2024, shows a drone jammer made by ChingKong Technologies. Human Rights Watch was unable to establish the location of the photograph. A pro-SAF account on March 12, 2024, posted four photographs (4) of the same model said to have been captured by the military from the RSF in Khartoum’s sister city of Omdurman.

Amnesty International reported in July 2024 about a photograph (4), published on X on April 22, 2024, showing an apparent SAF fighter, who the poster alleged was in Al Gezira state, carrying a SkyFend Hunter drone jammer gun, made in China.[31]

9M133M Kornet anti-tank guided missile

Country of origin: Russia

User: RSF and SAF

Human Rights Watch found 11 videos showing the RSF using Kornet anti-tank guided missiles, including in Darfur and in the Khartoum area. The Kornet has been in use in Sudan for years and the SAF has also used Kornet missiles.[32] It is unclear whether the RSF captured the Kornet missiles from the SAF or obtained them through other means. Citing US and Sudanese officials, the New York Times reported on September 29, 2023, that Kornet missiles used by the RSF in previous weeks in an assault against the SAF Armored Corps base in Khartoum were provided by the UAE.

Human Rights Watch geolocated one video (1) to be in El Fasher and confirmed that a second video (2) was filmed a few hundred meters east of El Fasher, the location originally identified by investigator Benjamin Strick.[33]

Another video (3) posted to X on April 22, 2024, and claiming to have been filmed on April 21, 2024, in El Obeid (Northern Kordofan) shows a fighter in the beige uniform of the RSF firing a Kornet missile at a vehicle, which catches fire. Two other videos that Human Rights Watch was also unable to geolocate show fighters in beige uniforms firing Kornet missiles. In one (4), posted to X on June 9, 2024, a man wearing a beige turban fires a Kornet missile from a rooftop.

RSF

Unidentified Attack VTOL Drone equipped with Yugoimport 120mm Thermobaric Munitions

Country of origin: unknown (drone), Serbia (projectiles)

User: RSF

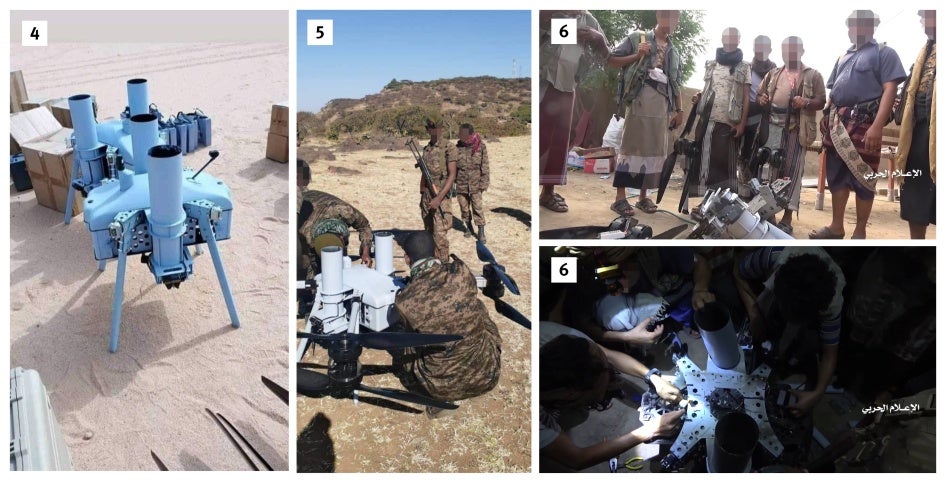

Human Rights Watch identified eight photographs and nine videos showing a distinctive quadcopter drone—with four rotors—in use by the RSF, which in some photographs and videos can be seen equipped with 120mm thermobaric munitions made by Serbian state-owned arms manufacturer Yugoimport. Thermobaric munitions are explosive munitions that use oxygen from the surrounding air to generate an enhanced, high-temperature detonation.

The first instance of the drone and its munition that Human Rights Watch found in use in Sudan was in a X post on June 2, 2023.

The munitions have a distinctive blue band painted on the body. Human Rights Watch identified the munition by comparing it to a model displayed by the manufacturer as well as to stencil markings on shipping crates found in Sudan.

Photographs from a post (1) from June, 13, 2023, show the munition affixed to an unidentified type of drone and show lot number markings on one of the munitions, indicating the munition was manufactured no earlier than 2020, which suggests that it could have been recently supplied to the RSF. On July 25, 2023, the pseudonymous account War Noir posted to X four photographs (2), two of which show a shipping crate of two of these munitions with markings indicating they were manufactured in 2020 and sent from Belgrade by Yugoimport to the UAE Armed Forces Joint Logistic Command in Abu Dhabi. A source who asked to remain anonymous because of the sensitivity of the issue told Human Rights Watch that the munitions were shipped to the UAE prior to the outbreak of the conflict in Sudan as part of a consignment whose end-user certificate prohibited re-exports.[34] In a video (3), posted to X on April 18, 2024, a SAF soldier shows six shipping crates of the same type of thermobaric munitions, two of which bear the same markings. The contract number visible on the crate indicates that the delivery to the UAE took place as part of a purchase order for a contract involving Adasi, a subsidiary of UAE-based weapons manufacturer, Edge Group.[35]

The drone appears to be a large drone retrofitted with two tubes designed to carry and drop the 120mm thermobaric munitions (4). Though the drone is manufactured according to a standardized design, it notably lacks visible markings, obscuring its origins. A nearly identical drone was used by the Ethiopian military in Ethiopia (5) and by an unknown force against Houthis in Yemen (6) in 2021.

One video (7) posted by a pro-RSF account on March 9, 2024, shows unidentified fighters looking at a drone of this model. The drone shows no signs of wear and is in the back of a pickup truck. The drone’s camera is clearly visible. Human Rights Watch identified the camera as a Chinese-made Viewprotech Q30TIR-50.

Human Rights Watch found four videos showing the live feed of a drone whose software interface researchers identified as being that of Viewprotech. In two of the videos, the drone drops Yugoimport thermobaric munitions, while in the other two videos, the drone drops a similar colored munition, but the markings used for identification are not visible.

In one of these videos (8), published by a pro-RSF account in March 2024, the live feed of a drone shows it dropping a 120mm thermobaric munition on an SAF fighter jet on the tarmac of the Wadi Saydna Air Base, a few kilometers north of Khartoum. The software interface also appears to be that of Viewprotech. Satellite analysis shows the strike took place sometime between the mornings of July 26 and July 27, 2023. Another video (9) published the same month shows, via a Viewprotech interface, a drone strike where a 120mm thermobaric munition is dropped on a pickup truck.

In the last two videos (10 and 11) posted in March 2024, which both show the Viewprotech interface, the munitions appear to be another type of a projectile not clearly identifiable. In one of these videos (11), verified by Human Rights Watch and published by a pro-RSF account in March 2024, the drone drops two munitions on defensive military positions on the Victory Bridge, which connects Khartoum to Omdurman.

Unidentified Truck-Mounted Multi-barrel Rocket Launcher

Country of origin: Unknown

User: RSF

Human Rights Watch verified one video (1) posted to Telegram in October 2023 showing two truck-mounted multi-barrel rocket launchers apparently in use by RSF forces in Khartoum. These are vehicle-based weapon systems designed for rapid deployment and saturation fire of rocket projectiles. The specific type of launcher, which consists of 40 tubes and is mounted on what appears to be a MAN truck, is unknown but appears to be capable of firing 122mm Grad-type unguided rockets or its equivalents. Another recording, posted to X in March 2024, of a screen recording of a video filmed from a drone (2), shows such a launcher after it was destroyed. Human Rights Watch was unable to determine the producer of the system or its origin.

One-Way Attack Drone

Country of origin: Unknown

User: RSF

On April 9, 2024, the RSF reportedly launched one-way attack drones for the first time since the conflict began, targeting the eastern city of Gedaref.[36] A one-way attack drone detonates when it hits its target.

Photographs posted on that day (1 and 2) by a pro-SAF Telegram account show remnants—including an engine—from such a drone that appears to have detonated, as well as fragmentation and thermal damage (3 and 4) apparently caused by the drone (5 and 6).

On August 3, 2024, a video and three photographs emerged online on a pro-SAF Telegram channel and on X that claimed in the accompanying caption that the SAF had captured several RSF one-way attack drones. These appear to be the same type of drones. There are no markings on the drone and the parts used are generic. An individual who inspected one of these drones told Human Rights Watch that it bore no markings and that the serial numbers of the drone’s components had been apparently deliberately scratched off.[37] The same engine is visible in parts allegedly recovered in a one-way drone attack on a government building in Gedaref on July 11 (6).

Human Rights Watch was unable to determine the maker of the drone.

Type PP87 Mortar Munitions

Country of origin: China

Users: RSF

The RSF appears to be using Chinese-made, newly manufactured and acquired mortar ammunition. Human Rights Watch was unable to verify RSF claims that it captured this new mortar munition from the SAF.

One video (1) posted on X on June 14, 2024, shows a man in RSF camouflage alongside a person in civilian clothing unpacking 82mm Mortar Long-Range HE shells Type PP87, a munition made in China by a state-owned company. The two men are surrounded by similar munitions and their boxes and plastic wrapping. One of the packages bears a marking (2) indicating it was produced in 2023. On November 11, 2023, the RSF posted a video (3) on its Telegram channel, showcasing munitions with the same packaging and markings, which it said it had captured from the SAF in Omdurman.[38]

SAF

Mohajer-6 attack drone

Country of origin: Iran, possibly manufactured in Sudan

User: SAF

Human Rights Watch found information showing that the SAF has been using Mohajer-6 drones, made by a company under the Iranian Ministry of Defense, which appear to have been supplied since the conflict broke out.[39] The Mohajer-6 is an uncrewed combat aerial vehicle capable of carrying precision-guided munitions and used in reconnaissance or attack missions.

Citing three Western officials, Bloomberg reported in January 2024 that Iran had supplied the SAF with Mohajer-6 attack drones.[40] “Six Iranian sources, regional officials and diplomats,” told Reuters in April 2024 that “the military had acquired Iranian-made unmanned aerial vehicles over the past few months.”[41] In June 2024, the BBC reported on the presence of Mohajer-6 in Sudan and on an apparent air bridge between Iran and Port Sudan involving a company, Qeshm Fars Air, which the US has previously sanctioned for “the delivery of lethal materiel” to Syria enabling “Iran’s military support for the Assad regime.”

Human Rights Watch analyzed one video (1) posted to the SAF Facebook page on May 9, 2024, which shows a strike on a building in Hillat ed Dareisa, roughly 45 kilometers north of Khartoum. Satellite analysis suggests the strike occurred between July 16, 2023, and November 26, 2023. While the interface has been blurred, the blurred elements match in size and location with elements that are visible on a known video feed (2) of the Mohajer-6 leading Human Rights Watch to conclude they are likely the same.

Two photographs (3) published on Telegram on January 6, 2024, show remnants characteristic of a Mohajer-6. In one of the photographs, RSF fighters are triumphantly brandishing the remnants, suggesting the RSF shot down a drone in use by the SAF. These emerged the same day as a video posted to the RSF Telegram consisting of two clips. The first shows a fighter in a beige uniform on a rooftop firing a shoulder-fired surface-to-air missile at a flying object. The second clip (3) shows men in a field similar to the first clip. Human Rights Watch was unable to confirm the location or that both scenes match. According to the RSF, this event took place in Khartoum.

Recommendations

To the United Nations Security Council

- Renew and ensure the enforcement of the mandate of the Sudan 1591 sanctions regime, which currently includes an arms embargo in relation to Darfur and mechanisms for travel bans and assets freezes.

- Broaden the arms embargo in place on Darfur to the whole of Sudan.

- Publicly condemn individual governments that violate the existing UN Security Council arms embargo on Darfur and impose sanctions on individuals or entities who are in violation of the arms embargo.

- In line with past recommendations of the Panel of Experts, the Darfur sanctions committee should develop a list of items that fall within the dual-use category, and whose transfer to Sudan or, at minimum, Darfur, should be restricted and subject to approval by the committee.[42]

To United Nations Member States, including Particularly Concerned

Regional States

- Press for action at the UN Security Council to enforce the existing arms embargo and expand it to the whole country.

- Press publicly and privately, and take appropriate action, to persuade states reportedly violating the existing arms embargo on Darfur to stop the provision of weapons to Sudanese warring parties in recognition that they are likely to be used in the commission of further war crimes or similar abuses against civilians.

- Suspend any arms, weapons and other military equipment transfers to Sudan, in line with applicable treaties regulating transfer of arms and other military and paramilitary equipment, including dual-use equipment, and to prevent such equipment being acquired and used by warring parties in Sudan to commit serious international humanitarian law violations against civilians in Sudan.

- Scrutinize carefully and, if appropriate, suspend any arms, weapons, and other military equipment transfers to third countries when there is a risk that they may be diverted to warring parties likely to use them to commit violations in Sudan.

To Sudan’s Neighboring Countries, including Chad, Egypt, South Sudan, Ethiopia

- Comply and ensure compliance with the UN arms embargo on Darfur.

[1] United Nations Security Council, Resolution 1556 (2004), S/RES/1556 (2004), United Nations Security Council, Resolution 1591 (2005), S/RES/1591 (2005).

[2] IISS, "The Military Balance 2022," (Routledge: London), February 2022, p. 497.

[3] See archive of reports by the UN Panel of Experts on the Sudan at https://main.un.org/securitycouncil/en/sanctions/1591/panel-of-experts/reports.

[4] Archived version of MIC’s Products page from May 10, 2029, https://web.archive.org/web/20190510152344/http://mic.sd/ar/home/products/ (accessed August 19, 2024).

[5] @TurtleYusuf post to X (formerly known as Twitter), June 14, 2024, https://x.com/TurtleYusuf/status/1801673099898691740.

[6] See Amnesty International, “New Weapons Fueling the Sudan Conflict, Expanding Existing Arms Embargo Across Sudan to Protect Civilians”, July 25, 2023. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/research/2024/07/new-weapons-fuelling-the-sudan-conflict/; @RSFSudan post to Telegram channel, November 15, 2023, https://t.me/RSFSudan/5354.

[7] The Sudanese Archive is a project by Mnemonic, a global non-profit organization dedicated to assisting human rights advocates in effectively using digital information related to human rights violations. The Archive includes media from X, Telegram, Facebook, YouTube, TikTok, and other social media platforms from or about Sudan since 2018. https://sudanesearchive.org/. Human Rights Watch searched the Sudanese Archive database for social media posts with photographs or videos captioned with the commonly used Arabic term for "drone," مسيرة . The search identified 39 posts tagged for drones out of more than 103,000 posts archived in 2022. There were 311 posts captioned with “drone” out of over 196,000 posts archived in 2023. As of August 2024, the archive contained 530 posts with “drone” out of 196,000 posts archived in 2024. A search for the plural of drones in Arabic, مسيرات, returned similar trends. Human Rights Watch did not inspect each individual piece of content. Results from ACLED, a database of political violence around the world, show the same trends. A search for the term “drones” returned no result for incidents in Sudan from mid-April until June 23, 2023, when the first incident involving drones was recoded. The number of such incidents rose sharply until October 2023, reaching over 70 per month then, with another spike at 80 in January 2024. They have stabilized at around 20-40 per month since – see https://acleddata.com. ACLED notes that the SAF was behind the overwhelming majority of instances of violence involving drones: “Since the outbreak of the war, ACLED records over 280 drone strikes conducted by the SAF. Nearly all of these strikes — 98% — were conducted in Khartoum state. In contrast, ACLED data indicate that the RSF has carried out at least 10 drone strikes.” ACLED, “Drone warfare reaches deeper into Sudan as peace talks stall,” Situation Update, August 23, 2024, https://acleddata.com/2024/08/23/drone-warfare-reaches-deeper-into-sudan-as-peace-talks-stall-august-2024.

[8] Human Rights Watch phone interviews with a SAF caporal and a major in the Sudanese Alliance (an armed group), November 2023; “The Massalit Will Not Come Home,” Human Rights Watch, May 9, 2024, https://www.hrw.org/report/2024/05/09/massalit-will-not-come-home/ethnic-cleansing-and-crimes-against-humanity-el; “Sudan: New Mass Ethnic Killings, Pillage in Darfur,” Human Rights Watch, November 26, 2024, https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/11/26/sudan-new-mass-ethnic-killings-pillage-darfur.

[9] Adasi claims to “focus on the acquisition, development, test, operation, training and full-service support of autonomous systems for air, land, and sea.” https://adasi.ae/about. A source that asked to remain anonymous because of the sensitivity of the issue told Human Rights Watch that the munitions were shipped to the UAE prior to the outbreak of the conflict in Sudan as part of a consignment whose end-user certificate prohibited re-exports. Human Rights Watch phone exchange with [name withheld], September 4, 2024.

[10] UN Panel of Experts on the Sudan, “Final report of the Panel of Experts on the Sudan,” S/AC.47/2024/PE/OC.1, January 14, 2024; New York Times, “Talking Peace in Sudan, the U.A.E. Secretly Fuels the Fight,” September 29, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/29/world/africa/sudan-war-united-arab-emirates-chad.html.

[11] @VleckieHond post to X (formerly known as Twitter), December 31, 2022, https://x.com/VleckieHond/status/1609195835085946881.

[12] Citing Western and Iranian sources, Bloomberg and Reuters reported in 2024 that the Iranian government had recently provided new drones to the SAF (see below). Bloomberg, Iranian Drones Become Latest Proxy Tool in Sudan’s Civil War, January 24, 2024, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-01-24/iran-supplies-sudan-army-with-drones-as-civil-war-continues; Reuters, “Sudan civil war: are Iranian drones helping the army gain ground?”, April 10, 2024. https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/are-iranian-drones-turning-tide-sudans-civil-war-2024-04-10/#:~:text=April%2010%20(Reuters)%20%2D%20A,senior%20army%20source%20told%20Reuters.

[13] Amnesty International, “New Weapons Fueling the Sudan Conflict, Expanding Existing Arms Embargo Across Sudan to Protect Civilians”, July 25, 2023. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/research/2024/07/new-weapons-fuelling-the-sudan-conflict/.

[14] UN Security Council resolution 1556 (2004), https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/n04/446/02/pdf/n0444602.pdf. Resolution 1556 imposed the arms embargo on non-state actors in Darfur; the embargo was expanded in 2005 to include all belligerents in Darfur. UN Security Council resolution 1591(2005), https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/n05/287/89/pdf/n0528789.pdf.

[15] Bromley M., Wezeman P.D., “Multilateral Embargoes on Arms and Dual-Use Items”, SIPRI Yearbook, 2018, Stockholm International Peace Institute, p.511, https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/SIPRIYB19c10sII.pdf; “Sudan: No end to violence in Darfur: Arms supplies continue despite ongoing human rights violations,” February 9, 2022, Amnesty International, https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/afr54/007/2012/en/; United Nations Security Council, Sanctions List, Gaffar Mohammed Elhassan, https://main.un.org/securitycouncil/en/sanctions/1591/materials/summaries/individual/gaffar-mohammed-elhassan; UN Panel of Experts on the Sudan, “Second report of the Panel of Experts established pursuant to paragraph 3 of resolution 1591 (2005) concerning the Sudan,” S/2006/250, paragraph 50, https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/n06/278/57/pdf/n0627857.pdf.

[16] Small Arms Survey, “Broken Promises – The Arms Embargo on Darfur since 2012”, HSBA Issue Brief, Number 24, July 2016. https://www.smallarmssurvey.org/sites/default/files/resources/HSBA-IB24-Darfur-Embargo.pdf

[17] Amnesty International, “New Weapons Fuelling the Sudan Conflict, Expanding Existing Arms Embargo Across Sudan to Protect Civilians”, July 25, 2023. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/research/2024/07/new-weapons-fuelling-the-sudan-conflict/

[18] Human Rights Watch geolocated a video posted on X on June 16, 2024, showing a drone filming as Grad-type artillery rockets hitting neighborhoods in central El Fasher around the Grand Market and the Grand Mosque; @SudanTribune_EN post to X (formerly known as Twitter), June 9, 2024, https://x.com/SudanTribune_EN/status/1799738259532333222; @war_noir post to X (formerly known as Twitter), June 16, 2024, https://x.com/war_noir/status/1802290281695334630.

[19] @RapidSupportSdn post to X (formerly known as Twitter), November 3, 2023, https://x.com/RapidSupportSdn/status/1720559997942214880.

[20] United Nations Security Council, Letter dated 15 January 2024 from the Panel of Experts on the Sudan addressed to the President of the Security Council, S/2024/65.

[21] UN Panel of Experts on the Sudan, “Final report of the Panel of Experts on the Sudan,” S/AC.47/2024/PE/OC.1, January 14, 2024, paragraph 40.

[22] UN Panel of Experts on Libya, “Final report of the Panel of Experts on Libya established pursuant to Security Council resolution 1973 (2011)”, S/2021/229, 2021, Annex 75, including Appendix D.

[23] Ibid. p. 28.

[24] FlySkyUA Official (@flyskyua) post to X (formerly known as Twitter) January 25, 2024, https://twitter.com/flyskyua/status/1353582947329339392?s=61&t=I64XhGx8w_L4NRs2TzRZBA.

[25] Human Rights Watch interviews with two humanitarian specialists in medical emergency deployments, July 2023 and April 2024.

[26] UN Panel of Experts on the Sudan, “Final report of the Panel of Experts on the Sudan,” S/AC.47/2024/PE/OC.1, January 14, 2024, paragraphs 42, 49.

[27] Permanent Mission of the United Arab Emirates to the United Nations, “Statement by the Permanent Mission of the United Arab Emirates to the UN in Response to False Allegations in the Letter Dated 10 June 2024 from the Representative of Sudan to the UN Security Council”, June 27, 2024, https://uaeun.org/statement/uae-response-to-false-allegations-sudan-27june/.

[28] For a documentation of other types of apparently recently acquired equipment used by the warring parties, including firearms made in Tÿrkiye, Serbia and Russia, Chinese-made anti-materiel rifles, firearms transferred from Yemen, and other types of UAE-made armored vehicles, see Amnesty International, “New Weapons Fueling the Sudan Conflict, Expanding Existing Arms Embargo Across Sudan to Protect Civilians”, July 25, 2023, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/research/2024/07/new-weapons-fuelling-the-sudan-conflict/.

[29] Radio Dabanga, “Unravelling Sudan’s militia matrix: PRF and other emerging forces”, September 26, 2023. https://www.dabangasudan.org/en/all-news/article/unravelling-sudans-militia-matrix-prf-and-other-emerging-forces

[30] The full letter is available at: https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/media_2024/09/DJI%20Drone%20Letter%20and%20Response.pdf.

[31] Amnesty International, “New Weapons Fuelling the Sudan Conflict, Expanding Existing Arms Embargo Across Sudan to Protect Civilians”, July 25, 2023, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/research/2024/07/new-weapons-fuelling-the-sudan-conflict/. Military Africa, a news website, also reported on the use by Sudanese warring parties of drone jammers manufactured by SkyFend and ChingKong Technologies. https://www.military.africa/2024/07/sudanese-forces-fields-chinese-ching-king-anti-drone-jammer/.

[32] The Sudan People’s Liberation Movement – North, an armed group, allegedly captured Kornets from the SAF in 2015. https://x.com/ALINGETHI/status/556061801243480064

[33] Post by Benjamin Strick on X, May 20, 2024, https://x.com/BenDoBrown/status/1792581339083923815.

[34] Human Rights Watch phone exchange with [name withheld], September 4, 2024.

[35] ADASI About Us Webpage, https://adasi.ae/about.

[36] Asharq al-Awsat, “RSF Drone Strikes on Sudan Army Targets Break Calm in Eastern City,” April 10, 2024, https://english.aawsat.com/arab-world/4958306-rsf-drone-strikes-sudan-army-targets-break-calm-eastern-city.

[37] Human Rights Watch phone conversation with an individual who inspected the drone in Sudan, August 19, 2024.

[38] Referring to an al-Arabiya report, Amnesty International noted that the same PP87 munition was used in al-Daen, South Darfur, in October 2023, in a violation of the arms embargo (p.25).Amnesty International, “New Weapons Fuelling the Sudan Conflict, Expanding Existing Arms Embargo Across Sudan to Protect Civilians”, July 25, 2023, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/research/2024/07/new-weapons-fuelling-the-sudan-conflict/.

[39] Reuters, “Sudan civil war: are Iranian drones helping the army gain ground?”, April 10, 2024. https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/are-iranian-drones-turning-tide-sudans-civil-war-2024-04-10/#:~:text=April%2010%20(Reuters)%20%2D%20A,senior%20army%20source%20told%20Reuters.

[40] Bloomberg, Iranian Drones Become Latest Proxy Tool in Sudan’s Civil War, January 24, 2024, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-01-24/iran-supplies-sudan-army-with-drones-as-civil-war-continues

[41] Reuters, “Sudan civil war: are Iranian drones helping the army gain ground?”, April 10, 2024. https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/are-iranian-drones-turning-tide-sudans-civil-war-2024-04-10/#:~:text=April%2010%20(Reuters)%20%2D%20A,senior%20army%20source%20told%20Reuters.

[42] See UN Panel of Experts on the Sudan, “Second report of the Panel of Experts established pursuant to paragraph 3 of resolution 1591 (2005) concerning the Sudan,” S/2006/250, https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/n06/278/57/pdf/n0627857.pdf.