Human Rights Watch welcomes the opportunity to provide input to the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the right to education ahead of her upcoming report to the Human Rights Council on academic freedom and freedom of expression in educational institutions. This submission covers autonomy of educational institutions, funding, surveillance, and freedom of expression in teaching and access to books. Our responses and examples in this submission are based on Human Rights Watch’s research findings and analysis.

Autonomy of Educational Institutions (question 4)

Autonomy and self-governance within educational institutions

- External actors can often impede independent decision-making within educational institutions, including in staff recruitment and appointment procedures.

- For example, in 2020, a hiring committee unanimously selected Dr. Valentina Azarova to direct the International Human Rights Program at the University of Toronto’s law school in Canada.[1] When the school’s dean stopped Azarova’s hire under disputed circumstances, the university commissioned a retired Supreme Court of Canada judge to review that decision.

- At the heart of concerns was that her appointment was blocked because some of her academic work was critical of Israel’s human rights record. The judge in his report acknowledged that after Azarova’s name was leaked to the Centre for Israel and Jewish Affairs (CIJA), a pro-Israel advocacy group, a quiet effort began to stop her appointment. He found that days before her appointment was terminated, a former board member of the lobby group, who is a major donor to the university, contacted the university after a CIJA official advised him to warn the university’s leadership that her hire would spark “a public protest campaign [that] will do major damage to the university, including in fundraising.”

- Despite these facts, the judge, who gave a keynote address at a conference hosted by the CIJA while conducting his review of the case, sided with the university’s claim that immigration issues were behind the decision and concluded that he “would not draw the inference that external influence played any role.” Several professors at the law school rejected the report, and the Canadian Association of University Teachers found the explanation for the termination so “implausible” that it censured the university for “a serious breach of widely recognized principles of academic freedom.” The university later offered Azarova the position, which she declined, and pledged to extend academic freedom protections to the directors of the human rights program and other clinical programs. For full disclosure, Dr. Azarova’s spouse works at Human Rights Watch.

- In Hungary, in September 2020, a new law transferred ownership of the state-run theater university to a private foundation whose members have close links to the Orban government.[2] The Ministry of Technology and Innovation appointed five members to the new board of trustees, rejecting members proposed by the university’s senate—the university’s main decision-making body. The government effectively controlled all appointments to the supervisory board and the board of trustees.

- The Orban government has spent the last decade exerting control over academia and sciences in an effort to root out teaching or scientific research that counters the government’s agenda. Examples include shutting down the Central European University, banning gender studies, and stripping the Academy of Sciences of its autonomy.[3]

- Teachers have been summarily dismissed under Hungary’s state of emergency law.[4] The events leading to the dismissals were prompted by an ongoing teachers’ protest against low salaries, poor working conditions, and the adoption of a law worsening the situation of teachers including by enabling monitoring phones, arbitrarily transferring teachers from one school to another, extending weekly working hours, and forcing teaching on Sundays.

Restrictions on police or military personnel entering educational institutions

- Human Rights Watch and the Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack have identified dozens of countries that have laws or policies restricting police or military personnel’s interactions with schools or universities.[5]

- For example, the Central African Republic, Ethiopia, and the Philippines make the occupation, confiscation, or appropriation of schools by armed groups or forces a criminal offense.

- Bangladesh, India, Ireland, Malaysia, Pakistan, Singapore, Sri Lanka, and the United Kingdom have legislation preventing military forces engaged in maneuvers to pass over, encamp, enter, or interfere with education institutions. Poland has legislation prohibiting the temporary quartering of armed forces personnel in higher education institutions.

- Albania, Argentina, Croatia, Montenegro, Nicaragua, North Macedonia, Peru, and Venezuela have legislation guaranteeing some measure of inviolability of their higher education institutions and their campuses from public order forces.

- Colombia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Denmark, Ecuador, Nepal, New Zealand, Nigeria, Norway, the Philippines, South Sudan, Spain, Sudan, Switzerland, Ukraine,[6] and the United Kingdom have either prohibitions or restriction on the use of their forces entering, occupying, or using schools or other education institutions, in military manuals, military orders, defense ministry directives, or other government guidance. Armed groups in Iraq, Lebanon, Libya, Mali, Myanmar, Syria, and Yemen have internal orders banning or restricting using schools for military purposes.

- In Colombia and India, courts have ordered security forces to stop occupying and using schools.

Funding (questions 6, 7)

- Universities in China are tightly controlled by a government notoriously hostile to academic freedom at home and abroad.

- Over the past decade, due to decreased state funding to higher education in Australia, Canada, the UK, and the United States, universities have been increasingly financially dependent on fee-paying students from China, and on Chinese government and corporate entities. This has made universities more susceptible to Chinese government influence.[7]

- Media reported in January 2022 that the Vrije Universiteit (Free University) of Amsterdam in the Netherlands had accepted funding between 2018 and 2020 from the Southwest University of Politics and Law in Chongqing, China. The funding to the Free University supported its “Cross Cultural Human Rights Centre,” which has articulated views strikingly similar to those of the Chinese government. For instance, several center employees denied that the Chinese government was oppressing Uyghurs, despite overwhelming evidence that the government is committing crimes against humanity against Uyghurs. The Free University later pledged to return the funding.[8]

- To help mitigate such risks to academic freedom, Human Rights Watch has proposed a code of conduct for colleges, universities, and academic institutions.[9] One key step is for universities to publicly disclose all direct and indirect Chinese government funding and list all projects and exchanges with Chinese government counterparts on an annual basis.

Surveillance (question 8)

- Surveillance practices by Russian and Chinese public authorities undermine academic freedom and teachers’ and children’s freedom of expression. We have also found that digital surveillance, including through the use of government-approved and often compulsory education technology (EdTech) during the Covid-19 pandemic, harmed children’s rights to education and privacy across the world.

- In Russia, authorities have surveilled and retaliated against Russian children who have expressed criticism of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.[10] For example, in October 2022, a police officer came to a school in Moscow and interrogated a 10-year-old girl about her pro-Ukraine social media avatar and a poll she ran in a school chat asking students what they thought about Russia’s war in Ukraine. Police interrogated the girl and her mother and conducted a “house inspection” where the police accessed their mobile phone and laptop looking for messages and social media publications “discrediting” the military. A juvenile affairs commission found the mother guilty of failing to fulfill parental duties and of “projecting her political opinions onto her daughter and failing to censor her social media activities.” They handed down a warning to the mother and put the family on record for further control. The family left Russia for fear of further retaliation.

- Students from China, Hong Kong, Xinjiang, and Tibet who participate in protests or engage in criticism of the Chinese Communist Party on foreign campuses have sometimes faced surveillance. At Australia’s universities, the surveillance, intimidation, and harassment of pro-democracy students from the mainland and Hong Kong has meant some students self-censor or change their behavior, fearful of the consequences.[11]

- Human Rights Watch verified three incidents involving Chinese university students in which police in China visited or asked to meet with their families regarding the student’s activities in Australia. The Chinese authorities threatened one student with jail after the student opened a Twitter account while studying in Australia and posted pro-democracy messages. Another student, who expressed support for democracy in front of classmates in Australia, had their passport confiscated by Chinese authorities upon returning home.[12]

- Every pro-democracy student interviewed expressed fears that their activities in Australia could result in Chinese authorities punishing or interrogating their family back home.

- Some faculty who specialize in China studies said they practiced regular self-censorship while talking about China’s human rights situation. We found that instances of censorship imposed by university administrators occurred but were less frequent. Administrators asked staff not to discuss matters the Chinese government considers “sensitive” like Xinjiang, Hong Kong, Taiwan, or Tibet publicly or discouraged them from holding public events or speaking to the media about certain human rights issues in China. Pro-Beijing students and social media users have also subjected some academics at Australian universities to harassment, intimidation, and doxing—posting of their personal information—if the academics are perceived to be critical of the Chinese Communist Party.

- In 2022, the Australian Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security released a report examining foreign interference at Australian universities, making recommendations to universities and the government, including mechanisms to report incidents of foreign interference; deterrence for students who report on activities of fellow students to foreign governments; and closer scrutiny of student associations linked to authoritarian governments.

- Some universities such as the University of New South Wales and the University of Technology Sydney have launched awareness campaigns for students and staff about the risks of foreign interference.[13] The Committee's report, coupled with updated guidelines from the University Foreign Interference Taskforce, are important steps to guarantee academic freedom in Australia.

- In Thailand, during the rule of the military National Council on Peace and Order (2014-2019) and subsequent military controlled government (2019-2023), the authorities forced the cancellation of community meetings, academic panels, issue seminars, and public forums on political matters, and especially issues related to dissent towards policies of the military junta or the state of human rights in Thailand.

- The International Conference on Thai Studies was held at Chiang Mai University in Thailand in July 2017.[14] Uniformed and plainclothes police officers, none of whom were registered for the conference, attended many of the sessions and photographed participants. In protest, some of the participants held a sign up in front of the seminar room that read “an academic forum is not a military camp,” and took a photo. In July 2018, the conference organizer, a translator, and three students who had held up the sign were indicted on charges of violating an order which authorized certain military officers to “prevent and suppress” offenses including sedition and violations of announcements or orders of the military junta. Although the case was later dismissed, the repercussions continued: a number of international academics who signed one of the many petitions in support of the defendants were detained by the Immigration Authorities or questioned by Special Branch when entering or leaving Thailand.

Surveillance in online learning

- During Covid-19-related school closures, governments across the world endorsed online learning products without adequately protecting children’s privacy.[15] Most of the 163 EdTech products reviewed by Human Rights Watch in 2021 monitored or had the capacity to monitor children, in most cases secretly and without the consent of children or their parents, in many cases harvesting data on who they are, where they are, what they do in the classroom, who their family and friends are, and what kind of device their families could afford for them to use.

- Most online learning platforms installed tracking technologies that trailed children outside of their virtual classrooms and across the internet, over time. Some invisibly tagged and fingerprinted children in ways that were impossible to avoid or get rid of. Most platforms sent or granted access to children’s data to third-party companies, usually advertising technology (AdTech) companies. In doing so, some EdTech products targeted children with behavioral advertising, not only distorting children’s online experiences, but also risking influencing their opinions and beliefs at a time in their lives when they are at high risk of manipulative interference. Many more EdTech products sent children’s data to AdTech companies that specialize in behavioral advertising or whose algorithms determine what children see online.

- Most countries in the world do not have modern child data protection laws that would provide protections to children in complex online environments, including safeguards around the collection, processing, and use of children’s data.[16]

Freedom of Expression in Teaching and Access to Books

- Human Rights Watch has long documented violations of the rights to freedom of expression and information in educational institutions. This includes access to comprehensive sexuality education.[17]

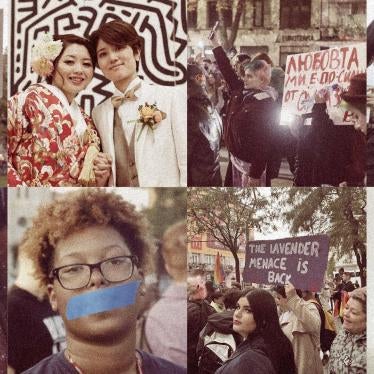

- In the United States, laws have been proposed or passed that restrict education about systemic racism and often also about gender, sexuality, or “divisive topics.” At least 7 states have enacted laws prohibiting classroom instruction on sexual orientation or gender identity, including inclusive discussions of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people and their families, and in several instances officials have removed books that address gender and sexuality from schools and public libraries.[18] Other laws change curricula to distort or omit historical accounts and contributions of specific racial or ethnic groups. In February 2023, the College Board—a nonprofit organization that administers tests and Advanced Placement courses—decided to water down its new Advanced Placement African American Studies course curriculum, under pressure from Florida Governor Ron DeSantis.[19] This decision is part of a long history of Black erasure and an alarming political example of right-wing politicians undermining democracy by limiting public access to history and ideas.

- Along with the banning of thousands of books, over 20 US states have enacted restrictions against Critical Race Theory, the teaching of structural racism and gender inequity. These attacks have grown to additionally target Black feminism, queer theory, intersectionality, and other frameworks that address structural inequality.[20] This censorship affects millions of students from preschool to college and university in areas impacted by the bans and significantly limits their understanding and awareness of racial justice.

- Following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russian authorities and their proxies worked to replace the Ukrainian education system in occupied Ukrainian territories with the Russian education system, teaching the Russian curriculum, in the Russian language.[21] Occupying authorities in these areas retaliated against Ukrainian teachers who refused to work under the Russian system. They pressured parents who did not want their children to study in the Russian language and under the Russian curriculum and threatened parents whose children study online in the Ukrainian school system with fines, detention, and deprivation of child custody.

- The Russian curriculum justifies the invasion, falsely portrays Ukraine as a “neo-Nazi state,” and strictly limits instruction in the Ukrainian language. In 2023, the Russian education ministry launched a new history textbook for grade 11 students. Human Rights Watch examined the textbook closely and found that it contains blatant falsehoods, distortions, and anti-Ukrainian propaganda.

- Occupation authorities use this textbook in classes in Russian-occupied areas of Ukraine, which in 2022 also received other textbooks taught in Russia. They also confiscated and destroyed Ukrainian school materials. Ukrainian children under occupation and Ukrainian children who were deported and now study in Russia also receive military training in schools. They receive indoctrination with extensive propaganda, as do Russian children, including during military training classes and the so-called “lessons about things that matter,” which were introduced by the Russian education ministry following the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, with the aim of boosting students’ “patriotism.”

- De facto authorities in Ukraine’s occupied territories have subjected some children who spoke Ukrainian in schools to ill-treatment. For example, a teacher from Melitopol who remains in contact with the family of a former student, under 18, told Human Rights Watch, “They put a bag on [his] head for speaking Ukrainian and dumped him thirty kilometers outside the city.”

- In Afghanistan, Taliban policies and practices are disproportionately harming girls and women by banning them from secondary and higher education. The Taliban are also jeopardizing education for Afghan boys: they have dismissed all female teachers from boys’ schools and made harmful changes to the curriculum.[22] Many boys are left to be taught by unqualified teachers or made to sit in classrooms with no teachers at all. Subjects including arts, sports, English, and civic education, have been eliminated.

Free expression regarding the Israel and Palestine hostilities

- Amid the escalation of hostilities between Israeli forces and Palestinian armed groups since October 7, 2023, Human Rights Watch documented a pattern of undue removal and suppression of protected speech including peaceful expression in support of Palestine and public debate about Palestinian human rights.[23] For example, on October 13, education authorities in Berlin, Germany gave schools permission[24] to ban students from wearing the Palestinian keffiyeh (checkered black and white scarf), displaying stickers with inscriptions such as “free Palestine” (or saying it), and displaying a map of Israel in Palestinian colors of white, red, black, and green, raising concerns about the right to free expression and possible discrimination.

- Academics in various countries have faced significant consequences in the form of silencing, censorship, and intimidation by some governments and private institutions as a result of non-violent advocacy for Palestinian rights or criticism of Israeli government policies. This includes undue pressure or restrictions on academic freedom.[25]

- Since October, increased numbers of cases of antisemitism have been reported at schools and universities across Europe.[26] In Germany, teachers reached out to antisemitism advice centers and civil society groups like Kreuzberger Initiative gegen Antisemitismus asking for assistance on how to deal with cases and how to speak to students about the hostilities.[27]

Comprehensive sexuality education

- Anti-gender movements have attempted to block or oppose comprehensive sexuality education in many parts of the world.[28] Opposition to sexuality education is sometimes justified by appealing to so-called “family” or “traditional” values, but is often rooted in harmful, stigmatizing, or patriarchal beliefs. It is also often linked to broader political efforts to limit civil and political rights, including the right to freedom of expression.[29]

- In Brazil, lawmakers and other public officials have used pernicious legal and political tactics to undermine and even prohibit gender and sexuality education.[30] Human Rights Watch interviews with public school teachers revealed that they were hesitant or fearful to address gender and sexuality in the classroom due to the legal and political efforts to discredit such material. Secondary school teachers said they were harassed for addressing gender and sexuality, including by elected officials and community members. Some teachers faced administrative proceedings for covering such material, while others were summoned to provide statements to the police and other officials.

- Human rights groups have for years called out these attacks on education. In 2018 and 2022, 80 education and human rights organizations published and updated a manual to protect teachers against censorship in the classroom.[31]

[1] Michael Page (Human Rights Watch), “University of Toronto’s Leadership Draws Fire Over Academic Freedom,” Human Rights Watch dispatch, April 28, 2021, https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/04/28/university-torontos-leadership-draws-fire-over-academic-freedom.

[2] Lydia Gall (Human Rights Watch), “Hungary Continues Attacks on Academic Freedom,” Human Rights Watch dispatch, September 3, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/09/03/hungary-continues-attacks-academic-freedom.

[3] Ibid., “Central European University Opens Vienna Campus After Hungary Ousting,” Human Rights Watch dispatch, November 18, 2019, https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/11/18/central-european-university-opens-vienna-campus-after-hungary-ousting; “Hungary Renews its War on Academic Freedom,” Human Rights Watch dispatch, July 2, 2019, https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/07/02/hungary-renews-its-war-academic-freedom.

[4] At least 13 teachers have been fired since June 2022 based on a May 2022 law extending the state of emergency due to the war in Ukraine. Edina Hajnal, “Hungary’s ‘revenge bill’ against teachers, students and parents,” Heinrich Böll Foundation, May 12, 2023, https://cz.boell.org/en/2023/05/12/hungarys-revenge-bill-against-teachers (accessed January 22, 2024).

[5] Except where noted, all examples can be found in Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack, “Protecting Schools from Military Use 2021: Law, Policy, and Military Doctrine,” October 2021, https://protectingeducation.org/wp-content/uploads/Protecting-Schools-from-Military-Use-2021.pdf (accessed January 9, 2024).

[6] Human Rights Watch, “Tanks on the Playground”: Attacks on Schools and Military Use of Schools in Ukraine (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2023), https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/media_2023/11/ukraine1123web_0.pdf.

[7] Within the Chinese Communist Party, a special section called the United Front Work Department (UFWD) is responsible for organizing outreach to key Chinese interest groups, including ethnic Chinese abroad, and representing and influencing them. Overseas Chinese students have long been a target of the United Front, but in 2015, this was reinforced when Xi Jinping designated them as a “new focus of United Front work.” See Human Rights Watch, “They Don’t Understand the Fear We Have”: How China’s Long Reach of Repression Undermines Academic Freedom at Australia’s Universities (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2021), https://www.hrw.org/report/2021/06/30/they-dont-understand-fear-we-have/how-chinas-long-reach-repression-undermines.

[8] Sophie Richardson (Human Rights Watch), “Dutch University Hit by Chinese Government Funding Scandal,” Human Rights Watch dispatch, January 20, 2022, https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/01/20/dutch-university-hit-chinese-government-funding-scandal.

[9] Human Rights Watch, “Resisting Chinese Government Efforts to Undermine Academic Freedom Abroad: A Code of Conduct for Colleges, Universities, and Academic Institutions Worldwide,” available at https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/supporting_resources/190321_china_academic_freedom_coc_0.pdf.

[10] For more details, see Human Rights Watch, “Russia: Submission to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child,” December 21, 2023, https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/12/21/russia-submission-un-committee-rights-child.

[11] “Australia: Beijing Threatening Academic Freedom,” Human Rights Watch news release, June 29, 2021, https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/06/30/australia-beijing-threatening-academic-freedom.

[12] Human Rights Watch, “They Don’t Understand the Fear We Have.”

[13] Sophie McNeill (Human Rights Watch), “How Australian universities are working to counter China's global attacks on academic freedom,” ABC News, April 4, 2022, https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/04/04/how-australian-universities-are-working-counter-chinas-global-attacks-academic.

[14] The conference, held annually, is hosted by different universities each year. Human Rights Watch, To Speak Out is Dangerous: Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Thailand (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2019), https://www.hrw.org/report/2019/10/25/speak-out-dangerous/criminalization-peaceful-expression-thailand.

[15] Human Rights Watch, “How Dare They Peep into My Private Life?”: Children’s Rights Violations by Governments that Endorsed Online Learning During the Covid-19 Pandemic (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2022), https://www.hrw.org/report/2022/05/25/how-dare-they-peep-my-private-life/childrens-rights-violations-governments.

[16] For more details, see ibid., section IV: Failure to Protect, “Child Data Protection Laws.”

[17] See Human Rights Watch, “Submission by Human Rights Watch to the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Privacy,” October 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/10/19/submission-human-rights-watch-un-special-rapporteur-right-privacy.

[18] Movement Advancement Project (MAP), “Equality Maps: LGBTQ Curricular Laws” (webpage) [n.d.], https://www.lgbtmap.org/equality-maps/curricular_laws (accessed January 25, 2024). See also Human Rights Watch, “Feminist Florida,” blog, https://www.hrw.org/blog-feed/feminist-florida.

[19] Human Rights Watch, “US: School Censorship Violates Basic Human Rights,” May 3, 2023, https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/05/03/us-school-censorship-violates-basic-human-rights.

[20] “Organizational Letter Endorsing the Freedom to Learn Campaign,” Human Rights Watch letter, May 3, 2023, https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/05/03/organizational-letter-endorsing-freedom-learn-campaign.

[21] For more details, see Human Rights Watch, “Russia: Submission to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child.”

[22] Human Rights Watch, “Schools are Failing Boys Too”: The Taliban’s Impact on Boys’ Education in Afghanistan (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2023), https://www.hrw.org/report/2023/12/06/schools-are-failing-boys-too/talibans-impact-boys-education-afghanistan.

[23] Human Rights Watch, Meta’s Broken Promises: Systemic Censorship of Palestine Content on Instagram and Facebook (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2023), https://www.hrw.org/report/2023/12/21/metas-broken-promises/systemic-censorship-palestine-content-instagram-and.

[24] Senatsverwaltung für Bildung, Jugend und Familie Berlin, Schreiben an alle Schulen des Landes Berlin im “Umgang mit Störungen des Schulfriedens im Zusammenhang mit dem Terrorangriff auf Israel,” October 13, 2023, https://www.tagesspiegel.de/berlin/downloads/umgang-mit-storungen-des-schulfriedens-im-zusammenhang-mit-dem-terrorangriff-auf-israel (accessed January 22, 2024).

[25] See for example “US rights group urges colleges to protect free speech amid Israel-Gaza war,” Al Jazeera, November 1, 2023, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/11/1/us-rights-group-urges-colleges-to-protect-free-speech-amid-gaza-war (accessed November 30, 2023), and Vima Patel and Anna Betts, “Campus Crackdowns Have Chilling Effect on Pro-Palestinian Speech,” New York Times, December 17, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/17/us/campus-crackdowns-have-chilling-effect-on-pro-palestinian-speech.html (accessed January 25, 2024).

[26] Human Rights Watch, “Israel-Palestine Hostilities Affect Rights in Europe,” October 26, 2023, https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/10/26/israel-palestine-hostilities-affect-rights-europe.

[27] Juedische Allgemeine, “Immer mehr Antisemitismus an Schulen und Unis,” December 10, 2023, https://www.juedische-allgemeine.de/unsere-woche/immer-mehr-antisemitismus-an-schulen-und-unis/ (accessed January 31, 2024), and Jenny Barke, “Was tun gegen den Antisemitismus an Berliner Schulen?,” rbb24, October 10, 2023, https://www.rbb24.de/politik/beitrag/2023/10/nahost-konflikt-berlin-schule-kiga-vermittlung-antisemitismus.html (accessed January 31, 2024).

[28] For more country examples, see for instance Human Rights Watch, No Support: Russia’s “Gay Propaganda” Law Imperils LGBT Youth (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2018), https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/12/12/no-support/russias-gay-propaganda-law-imperils-lgbt-youth; Cristian González Cabrera (Human Rights Watch), “Censoring Sexuality Education is Not a ‘New Idea’,” El Mundo, October 11, 2o22, https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/10/11/censoring-sexuality-education-not-new-idea; “Poland: Veto Bill Targeting Sex Ed,” Human Rights Watch news release, December 8, 2022, https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/12/09/poland-veto-bill-targeting-sex-ed; and Ryan Thoreson, “UN Body Urges South Korea to Improve Sexuality Education,” Human Rights Watch dispatch, October 16, 2019, https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/10/16/un-body-urges-south-korea-improve-sexuality-education.

[29] See for example Mauricio Albarracín-Caballero (Human Rights Watch), “How Targeting LGBTQ+ Rights Are Part of the Authoritarian Playbook,” Advocate, September 6, 2022, https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/09/06/how-targeting-lgbtq-rights-are-part-authoritarian-playbook.

[30] Human Rights Watch, “I Became Scared, This Was Their Goal”: Efforts to Ban Gender and Sexuality Education in Brazil (New York: Human Rights Watch, 2022), https://www.hrw.org/report/2022/05/12/i-became-scared-was-their-goal/efforts-ban-gender-and-sexuality-education-brazil.

[31] Defense Manual Against Censorship in Schools, 2022, available at https://manualdedefesadasescolas.org.br/ (accessed January 25, 2024).