Human Rights Watch submission to the UN Special Rapporteur on violence against women and girls

Human Rights Watch (HRW) is pleased to have the opportunity to offer input for the upcoming report on prostitution and violence against women and girls, which will be presented to the UN Human Rights Council at its 56th session in June 2024.

HRW has conducted research on sex work around the world, including in Cambodia, China, Greece, South Africa, Spain, Tanzania, and the United States. This included extensive consultations with sex workers, sex worker rights defenders, anti-trafficking organizations, and other experts. It shaped the HRW policy on sex work, including the language used to speak about sex work, trafficking for sexual exploitation, and consent.

In more than a decade of investigations in countries with different political and socio-economic realities, the fundamental findings have not changed. Criminalization, including partial criminalization, increases violence, discrimination, and sexual assault while having no demonstrable effect on eradicating trafficking. The use of criminal law to regulate women’s bodies is not an effective tool for their protection.

This submission focuses on the following themes:

- Accuracy and respect when speaking about sex work and trafficking;

- The causal relationship between violence against women and criminalization (Question 4);

- How stigmatizing, dehumanizing language normalizes violence against women (Question 4);

- Legislative frameworks (Question 9);

- Obstacles faced by organizations (Question 12);

- The ability of sex workers to give and withdraw consent (Question 8).

- Accuracy and respect when speaking about sex work and trafficking

On 12 January, Human Rights Watch submitted a letter to the Special Rapporteur clarifying the report’s subject (Annex A).

The Call for submissions’ title highlights prostitution, but the text addresses both sex work and trafficking. The report seeks to address “the nexus between the global phenomenon of prostitution and violence against women and girls,” but the Call repeatedly cites international law related to trafficking. In several instances, it uses trafficking and prostitution interchangeably.

As areas of investigation and under international law, these are three distinct concepts: trafficking into sexual exploitation, trafficking into labor exploitation, and sex work (Annex A).

HRW investigative findings and policy analysis related to sex work and trafficking for sexual exploitation are provided in answer to questions about “prostituted women and girls.” HRW does not use this phrase to refer to either adult sex workers or adult or child survivors of trafficking for sexual exploitation.

In the future, and in the report, it is strongly recommended that the Special Rapporteur use “sex work” when referring to women who call themselves “sex workers,” not only out of respect for the women involved, but also for legal clarity.

- The causal relationship between violence against women and criminalization (Question 4)

HRW investigations have found that sex workers face physical, psychological, sexual, economic, and other forms of violence from a wide range of perpetrators, including police, clients, health care providers, government bodies, and others. Our research has repeatedly found that the criminalization of sex work, prostitution, and related themes – including partial criminalization, discussed below – exacerbates, or is one of the underlying causes, of much of this violence, making decriminalization a critical step in the eradication of violence against sex workers and survivors of trafficking for sexual exploitation.

HRW research in South Africa found that criminalization of sex work fuels human rights violations, including by police officers, and undermines women’s right to health. Police officers use the criminality of sex work to coerce sex workers into having sex with them and threaten to arrest them if they refuse. The context of criminality leads to rampant underreporting of abuses against sex workers due to the legitimate fear of retaliation. In one case study from a 2019 HRW report:

“Rofhiwa Mlilo [a 40-year-old sex worker and a single mother of two children] described ... arbitrary arrests, lack of due process, and abusive policing practices. One policeman ‘arrested’ her and tried to make her have sex with him. When she was raped by a man who threated her with a broken bottle, she didn’t report because she could not see the police taking her seriously.”

In China, where sex work is also illegal, HRW documented arbitrary arrests and detentions, physical violence, and other ill-treatment of sex workers. Women in Beijing told HRW that possession of condoms was frequently used as evidence against them, putting them in the impossible position of risking their health or their liberty. Others were detained following sex with undercover police officers.

In Tanzania, HRW found physical and sexual violence, including rape, perpetrated by police. Identity-based arrests also take place, in which police arrest someone solely because they are known as a “sex worker.” Research from other human rights organizations uncovered identity-based arrests in Myanmar, Kyrgyzstan, and El Salvador, and found transgender women and women living in impoverished communities to be especially at risk of profiling and abuse.

- How stigmatizing, dehumanizing language normalizes violence against women (Question 4)

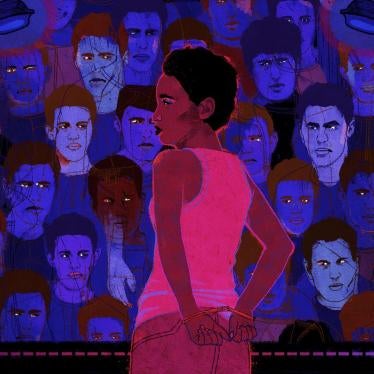

Objectifying, patronizing, and dehumanizing language – including “prostituted women” – is directly tied to several forms of violence that women face, in part because it normalizes that violence.

A 2017 article published by the Journal of Sex Research found that stigmatization "plays a role in fostering an environment where disrespect, devaluation, and even violence are acceptable". The term “prostitute,” except in cases in which it is explicitly reclaimed by affected communities, connotes criminality and discursively suggests that sex workers are deserving of punishment (Annex A).

The language used to discuss sex work and trafficking should be respectful and precise, so as not to further the dehumanization of the women. Sex workers should lead discussions about their lives and be supported to participate meaningfully in policy forums.

- Legislative frameworks and the prevention of violence against women (Question 9)

Human Rights Watch supports the full decriminalization of consensual adult sex work and encourages all governments to enact data-driven policies to save women’s lives.

HRW research, as well as credible investigations and analysis from academics, health journals, anti-trafficking organizations, UN women’s rights bodies, and sex workers themselves, consistently find that criminalization of the demand or supply of sexual services makes sex workers more vulnerable to violence, including rape, assault, and murder, while having no demonstrable impact on the eradication of trafficking.

Credible research consistently shows that criminalizing the purchase of sex (Nordic Model, Equality Model, Partial Criminalization, or End Demand Model) pushes the sale of sex into more secluded areas. This has several harmful impacts for both sex workers and survivors of trafficking for sexual exploitation, including forcing women to abandon basic safety strategies, such as:

- Working together because the law criminalizes doing so;

- Recording license plates, phone numbers, and faces of clients before heading into a private area because clients fear being or parking in public areas for long periods of time.

It also exposes sex workers to increasingly brutal physical and sexual violence by police and abusers. Médecins du Monde research found that the 2016 introduction of partial criminalization in France created a fear of arrest for clients, which forced street sex workers into dangerous locations. Soon after there was a spike in gruesome murders, with 10 sex workers killed in France in a six-month period.

Partial criminalization is predicated upon a contradiction: it treats women who sell sex as both victims and perpetrators. HRW’s analysis of several states’ legal codes concluded that terms such as “prostitution” and “prostituted person” create significant, problematic legal ambiguity which puts women at risk. Ireland’s 2017 law criminalizing the purchase of sex, for example, brought harsher penalties for sex workers found guilty of brothel-keeping and “living on earnings of prostitution”. Sex workers who share a flat now face possible arrest for keeping a brothel and a €5,000 fine or 12 months in prison. These punishments are for “prostituting” one another, when in reality women share space to protect one another. Partial criminalization functions as the full criminalization of womenand their collective protection tactics.

- Obstacles faced by organizations and frontline service providers in their mission to support victims and survivors (Question 12)

Women human rights defenders who are sex workers are experts in the lived realities of their communities. They possess the skills and knowledge to address human rights violations to which both sex workers and survivors of trafficking for sexual exploitation are subjected. However, they endure risks, threats, stigma, and backlash for their life saving work.

A 2021 investigation by Front Line Defenders interviewed more than 350 sex worker rights defenders and sex workers in more than a dozen countries. The investigation revealed widespread attacks on sex worker rights defenders including:

“arrest; sexual assault in detention; raids on their homes and offices; immense psychological pressure; threats from managers, family, and clients; physical attacks; police surveillance while conducting health outreach work; public defamation campaigns; extreme financial burdens as a result of activism; and discriminatory exclusion from policy making in areas in which they have clear, demonstrable and unmatched expertise.”

In the same report, advocates defending the rights of both sex workers and survivors of trafficking reported dozens of cases in which—although they were exclusively engaged in human rights work and were not selling sex—the acts of meeting, gathering testimonies, engaging in community outreach, and publicly advocating for their rights put them at risk of arrest under existing anti-prostitution laws.

Criminalization also makes the work of anti-trafficking, health, and women’s rights organizations more dangerous and difficult. As HRW previously stated in its Letter from Human Rights Watch to the Spanish Congress of Deputies for Proposed Law on Pimping, research demonstrates that criminalization causes establishment managers (such as in hotels, massage parlors, and karaoke bars) to deny that sex work happens on their premises. This makes it harder and more dangerous for advocates to enter, leaving the women inside with even fewer resources and witnesses.

Criminalization endangers and undermins human rights defenders’ ability to negotiate access to brothels, identify sexually exploited children, train survivors on accessing justice, offer harm reduction, help women plan escape routes, and provide health care for survivors deprived of freedom of movement.

- The ability of sex workers to give and withdraw consent (Question 8)

Women’s autonomy is essential to achieving gender equality. Any regulation that denies women’s consent must be subject to extreme scrutiny, used in exceptional circumstances, and carefully crafted to respect women's rights.

In the case of trafficking in persons, Article 3 of the UN Trafficking in Persons Protocol states that consent of a victim is irrelevant if certain “means” have been used. It requires both a third person “trafficking” another person and the conditions indicated in the article for consent to be irrelevant.

As stated in a UN Office of Drugs and Crime paper:

“the requirement to show ‘means’ affirms that, at least within the Protocol, exploitative conditions alone are insufficient to establish trafficking of adults: Agreement to work in a situation that may be considered exploitative will not constitute trafficking if that agreement was secured and continues to operate without threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, abduction, fraud, deception, abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person.”

Additionally, a trafficking survivor retains the ability to consent, not consent, or give and then withdraw consent to many factors such as: working with authorities to bring perpetrators to justice; not seeking support for fear of being deported; or continuing to sell sex for economic reasons.

In the case of sex work, to imply that all sex work is sexual exploitation is to say that women do not know the difference between sex and rape. Sex workers can and do:

- give and rescind consent about the location, time, place, labor to be performed, and payment, as with any worker;

- give and rescind consent about if, when, how, with whom, and for how long they will have sex, as with any person who has sex.

From an exploitation perspective, unilaterally denying women’s ability to consent to sex work precludes their ability to refuse or withdraw consent to a wide array of abuses which happen while working.