“Treat Us Like Human Beings”

Discrimination against Sex Workers, Sexual and Gender Minorities, and People Who Use Drugs in Tanzania

Glossary

Biological Sex: Biological classification of bodies as female or male based on factors such as external sex organs, internal sexual and reproductive organs, hormones, and chromosomes.

Bisexual: Sexual orientation of a person who is sexually and romantically attracted to both women and men.

Gay: Synonym in many parts of the world for homosexual; used here to refer to the sexual orientation of a man whose primary sexual and romantic attraction is towards other men.

Gender: Social and cultural codes (as opposed to biological sex) used to distinguish between what a society considers "masculine" or "feminine" conduct.

Gender-Based Violence: Violence directed against a person based on gender or sex. Gender-based violence includes sexual violence, domestic violence, psychological abuse, sexual exploitation, sexual harassment, harmful traditional practices, and discriminatory practices based on gender.

Gender Identity: Person’s internal, deeply felt sense of being female or male, both, or something other than female and male. It does not necessarily correspond to the biological sex assigned at birth.

Heterosexual: Person whose primary sexual and romantic attraction, or sexual orientation, is toward people of the other sex.

Homophobia: Fear and contempt of homosexuals, usually based on negative stereotypes of homosexuality.

Homosexual: Sexual orientation of a person whose primary sexual and romantic attractions are toward people of the same sex.

Intersex People: People born with reproductive or sexual anatomy that does not seem to fit the typical definitions of “female” or “male”; for instance, they may have sexual organs that correspond to both sexes.

Key Populations/Key Populations at Higher Risk of HIV Exposure: Those most likely to be exposed to HIV or to transmit it. In most settings, those at high risk of HIV exposure include men who have sex with men, transgender persons, people who inject drugs, sex workers and their clients, and HIV-negative partners in serodiscordant couples (couples in which one partner is HIV-positive and one is HIV-negative). Each country should define the specific populations that are key to their epidemic and response based on the epidemiological and social context.[1]

LGBTI: Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex; an inclusive term for groups and identities sometimes associated together as “sexual minorities.”

Lesbian: Sexual orientation of a woman whose primary sexual and romantic attraction is toward other women.

Maskani: Kiswahili slang term used to signify an outdoor location for using drugs.

Men Who Have Sex With Men (MSM): Men who have sexual relations with persons of the same sex, but may or may not identify themselves as gay or bisexual. MSM may or may not also have sexual relationships with women.

Most At-Risk Populations (MARPs): Used by public health workers to describe groups likely to be exposed to HIV or to transmit it. This report uses the terms “key populations” and “most at-risk populations” interchangeably. It also uses the terms “marginalized groups” and “vulnerable groups,” to refer collectively to sexual and gender minorities, sex workers, and people who use drugs.

Panga: Kiswahili word for machete.

People Who Inject Drugs/People Who Use Drugs: Used here instead of “injecting drug users” (IDUs) or “drug users,” terms that some drug users reject as defining them based on drug use alone. In Kiswahili, the non-pejorative slang term “teja” (plural: “mateja”) is often used to refer to people who use drugs; “mtumiaji wa madawa ya kulevya” (literally, person who uses drugs) is also used.

Police Form Number 3 (PF3): Form that police must fill out before most Tanzanian hospitals will treat victims of assault.

Police Jamii: Community police; groups of civilians in mainland Tanzania and Zanzibar that provide information to the police and in some cases carry out patrols.

Sexual Minorities: Inclusive term that includes all persons with non-conforming sexualities and gender identities, such as LGBTI, men who have sex with men (and may not self-identify as LGBTI) and women who have sex with women.

Sexual Orientation: The way a person’s sexual and romantic desires are directed. The term describes whether a person is attracted primarily to people of the same sex, the opposite sex, or to both. Kiswahili, Tanzania’s national language, has a number of derogatory terms to describe people whose sexual orientation is not heterosexual. They include “shoga” and “msenge” (used to refer to men who have sex with men) and “msagaji” (used to refer to women who have sex with women). These terms are sometimes used by LGBTI people themselves in a non-derogatory way to refer to themselves or community members. “Mtu mwenye uhusiano we jinsia moja” (“a person having same-gender relationships”) is a neutral, non-offensive way to refer to someone who has same-sex relationships.

Sex Workers: Used here to refer to adult women and men who provide sexual services in exchange for money. Child sex work is strictly prohibited under international law and is a form of commercial sexual exploitation. Children engaged in sex work, however, should never be treated as criminals but are entitled to protection from the state from such exploitation and provided with appropriate assistance.

Sungu Sungu: Initially used to refer to a vigilante group formed to combat cattle rustling in western Tanzania in the 1980s; more recently, the term has come to be used to describe any neighborhood militia. (Also “Sungusungu.”)

Transgender: The gender identity of people whose birth gender (which they were declared to have upon birth) does not conform to their lived and/or perceived gender (the gender that they are most comfortable with expressing or would express given a choice). A transgender person usually adopts, or would prefer to adopt, a gender expression in consonance with their preferred gender, but may or may not desire to permanently alter their bodily characteristics in order to conform to their preferred gender.

Women Who Have Sex With Women (WSW): Women who may or may not identify as lesbian or bisexual; some WSW may also have sexual relationships with men.

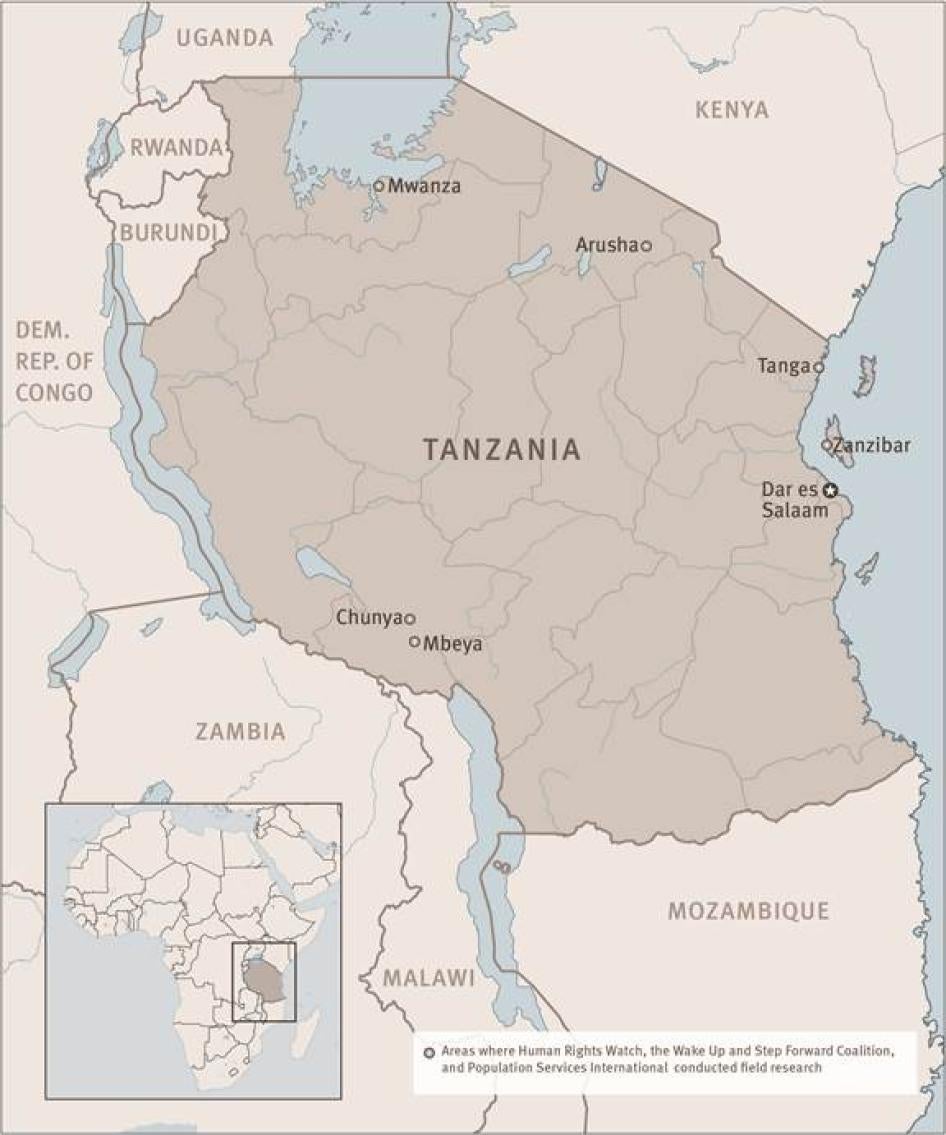

Map of Tanzania

© 2013 Human Rights Watch

Summary

In December 2010, police arrested Saidi W., an 18-year-old man in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, who identifies as gay. A police officer forced him at gunpoint to call five gay friends and tell them to meet him at a bar. When they arrived, the police arrested all of them, undressed them at the bar, beat them, and took them to Central Police Station. There the men were repeatedly raped by fellow detainees. When Saidi and his friends asked the police for help, police said, “This is what you want.” Saidi’s mother had to pay 400,000 Tanzania shillings (Tsh) (about US$250) as a bribe to release her son and his friends.

* * *

In 2012, Mwamini K., a female sex worker, was raped at gunpoint by a client who got angry when she asked that he use a condom. Mistrustful of police and hospitals, she was afraid to seek help: in 2011, when she was in the street in Dar es Salaam soliciting clients, three police officers caught her, called her a “dog” and a “pig,” and beat her for about 10 minutes before leaving her in the street. On that occasion, Mwamini went to the hospital for treatment, but told hospital workers that she had fallen down the stairs, afraid that she would be denied services if she told the truth about how she was beaten. She had also had problems with hospitals in the past: at one hospital, staff refused to treat her when she told them she had been infected with a sexually transmitted infection (STI) because of her sex work.

* * *

In December 2011, Dar es Salaam police arrested and tortured Suleiman R., who uses heroin, in an effort to extract a confession for a robbery he said he had not committed. They struck him with iron bars and burned his arm with a clothes iron. Police held Suleiman overnight and made his mother pay a Tsh 200,000 bribe ($125) to have him released the next day. Upon release, Suleiman asked the police to provide him with Police Form Number 3 (PF3), which public hospitals require before treating victims of assault. The police refused, saying, “If we give you a PF3, you will accuse the police in court.” Suleiman was forced to seek expensive treatment at a private hospital.

* * *

Saidi W., Mwamini K., and Suleiman R. have at least two things in common. First, they all belong to what public health specialists seeking to address the HIV/AIDS epidemic (see Glossary) refer to as “most at-risk populations” (MARPs) or “key populations.” While HIV prevalence among the general population has decreased in Tanzania, available data suggest it has increased among key populations, including men who have sex with men (MSM), sex workers, and people who inject drugs.

They also share another dubious distinction: Tanzanian law considers them all to be criminals. This criminal status drives them underground, making them easy targets for human rights violations by law enforcement officials; legitimizing stigma among the broader public; and giving government bodies an excuse to devote inadequate attention to key populations.

This report results from research conducted between May 2012 and April 2013 by Human Rights Watch and Wake Up and Step Forward Network (WASO), a Dar es Salaam-based network of groups that represent men who have sex with men. It documents human rights violations experienced by sex workers, people who use drugs, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex people (LGBTI), including MSM. It also exposes the very troubling situation of sexual exploitation of children in sex work. The report highlights two main categories of human rights violations: those for which law enforcement officials bear primary responsibility, and those within the health sector.

Violations by the Police

The research documents dozens of grave human rights violations by the police, including torture and rape, assault, arbitrary arrest, and extortion, as well as refusal to accept complaints from members of vulnerable groups that have been victims of crime. In one especially horrific case, police arrested John Elias, a heroin user, in a drug bust in the Kigamboni area of Dar es Salaam in February 18, 2010. At the police post, a police officer injected both of Elias’s eyes with a syringe full of liquid. A week later, when Elias went to the hospital, he discovered the liquid was acid. Today, Elias has gaping holes where his eyes should be.

Semi-official security forces, most notably the Sungu Sungu, a vigilante group, are also implicated in violence against at-risk populations, “policing” their behavior, often through the use of force. Their abuses include an attack on Mwanahamisi K. near the railroad in Tandika, Dar es Salaam, in May 2012, where she had gone to smoke heroin. She told Human Rights Watch: “Six of them forced me to have sex with them…. They didn’t use condoms. The rape lasted one or two hours. I was with my child. The baby boy was lying on the ground to the side while I was being raped…. After raping me, they told me “Don’t move around at night.”

Further reinforcing the second-class status of vulnerable groups, police sometimes refuse to accept complaints when sex workers, people who use drugs, or LGBTI people are victims of crime, whether by the security forces themselves or by private citizens. As a public health worker in Mwanza explained, “Sex workers do not have a place to speak against injustices done to them, and the police can take advantage of them if they go and report. If they go to the police, the police just become their customers for that night.”

All of these human rights violations reinforce stigma and contribute to an environment in which men who have sex with men, sex workers, and people who inject drugs become increasingly marginalized and distrustful of the state, undermining public health initiatives that depend on cooperation and partnership between the government and populations that are most at risk of HIV infection.

Among all three key populations, our research suggests that those who are the most vulnerable to police abuse are from lower socioeconomic classes. In all cases highlighted here, state actors and their proxies operate with impunity.

Violations within the Health Sector

Human rights violations within the health sector include denial of services, verbal harassment and abuse, and violations of confidentiality. Such incidents include a 2011 case in Dar es Salaam’s Temeke hospital when staff refused to use anesthesia when stitching up a person who uses drugs after he was attacked by a mob, and an incident in March 2012 when a doctor at Zanzibar’s Mnazi Mmoja Hospital refused to treat a gay man for gonorrhea, declaring, “You already have sex with men, now you come here to bring us problems. Go away.”

The report also documents onerous requirements in the health sector that, while not intended to discriminate, pose particular obstacles to access to health care for men who have sex with men, sex workers, and people who use drugs. For example, Jamila H., a sex worker, was gang-raped in February 2012 and went to a public hospital, but she was told she needed the police to fill out a form about the assault before she could receive treatment. “They said I should go to the police, but I couldn’t because I was a sex worker,” she said. Two of her rapists had not used condoms, but without access to hospital services, she did not get tested for HIV. Halima Y., also a sex worker, said health workers at Mwananyamala Hospital in Dar es Salaam refused to treat her for an STI because she could not comply with a requirement to bring in her sexual partner for testing and treatment.

Discriminatory treatment, combined with the absence of clear messages from the government that no one will be arrested or persecuted for seeking services, leads people to stay away from health services. When police or semi-official vigilante groups mistreat or arbitrarily arrest members of any marginalized group, or when health workers deny them services, their actions also violate clear international human rights principles, and also often violate Tanzanian law.

Most At-Risk Populations (MARPs)/Key Populations

The Tanzanian Ministry of Health and Social Welfare, like many health ministries around the world, has recognized that men who have sex with men (MSM), sex workers, and people who inject drugs are essential partners in the fight against HIV.

Tanzania’s Second National Multi-sectoral Strategic Framework on HIV and AIDS, 2008-2012, recognized that stigma inhibits access to services. (An updated strategic framework for 2013 to 2017 was being drafted as of this writing.) The Strategic Framework set forth several strategies aimed at reducing the risk of infection among the “most vulnerable,” including men who have sex with men, sex workers, and people who inject drugs. These included three particularly critical strategies. The framework pledged, in its own words:

- To promote increased access to HIV preventive information and services (IEC [Information, Education and Communication], condom access, peer education, friendly testing and counseling and STIs services) for the vulnerable populations.

- To build partnerships between government and CSOs [civil society organizations] and other agencies working with vulnerable populations to advocate for their empowerment and protection and stimulate documentation and exchange of experiences.

- To acknowledge the vulnerability of sex workers and men who have sex with men and advocate for their access to HIV preventive information and services and for decriminalization of their activities. (The Kiswahili version of the Strategic Framework uses slightly different language, discussed below.)

In Zanzibar—a semi-autonomous territory that maintains a political union with Tanzania, but has its own parliament and president—the National HIV Strategic Plan II (2011-1016) does not specifically call for decriminalizing sex work or consensual sex amongst men, but it recommends a national advocacy campaign promoting tolerance toward key populations. It also calls for other progressive measures, including needle exchange for people who inject drugs and for condoms and water-based lubricant to be distributed to men who have sex with men.

Unfortunately, existing law, combined with abusive practices by both law enforcement and health officials, undermines all these strategies, both in the mainland and in Zanzibar.

Criminals under the Law

Tanzanian law criminalizes consensual sexual conduct between adult males, with a penalty of 30 years to life in prison, one of the most severe punishments for same-sex intimacy in the world. Zanzibar has slightly different laws but criminalizes both male homosexual conduct and lesbianism. In both regions, prosecutions for same-sex conduct have not taken place in recent years, but the law—and the abusive way that it is often enforced—keeps lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) people marginalized. It also makes them more vulnerable to police blackmail and extortion as they seek to maintain their secret status.

Tanzanian law also criminalizes sex work: loitering for the purposes of prostitution carries a three-month prison penalty on the mainland, and providing sex in exchange for money carries a three-year penalty in Zanzibar.

Personal use of any narcotic drug or psychotropic substance is punishable by 10 years in prison on the mainland, a fine of Tsh 1 million (about $614), or both. In Zanzibar, it is punishable by up to seven years in prison.

Children

The use, offer, procurement, or provision of a child under 18 years old for sex work is a form of commercial sexual exploitation. This is prohibited under both Tanzanian and international law. Children who engage in sex work, or are otherwise commercially sexually exploited, should not be prosecuted or penalized for having been party to illegal sex work, but should receive appropriate assistance. Those who commit crimes of sexual exploitation should be prosecuted. However, commercial sexual exploitation of children—especially of girls—is frequent in Tanzania and usually goes unpunished. Moreover, children engaged in sex work with whom we spoke are frequently victims of police abuse and have no remedy against violence by private actors. Some of the most serious human rights violations we documented involved police raping children involved in sex work. For instance, Rosemary I., a child engaged in sex work in Mbeya, told us that police had raped her “about seven times,” the first time when she was just 12. According to the US State Department, no one was prosecuted in Tanzania in 2012 for sexual exploitation of children.

Limited Progress

Some progress has been achieved under the existing Strategic Framework and Strategic Plan, with a few state hospitals and some nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) throughout the country providing “MARPs-friendly” services. The government has also, through its health agencies, supported several outreach programs implemented by local and international organizations that target key populations. However, health workers continue to discriminate against patients based on their presumed sexual orientation, engagement in sex work, or drug use, compromising their right to the highest attainable standard of health.

The conduct of Tanzanian state agents systematically undermines the framework’s strategies, including its pledge to “promote increased access to HIV preventive information and services,” including “friendly testing,” to vulnerable groups. Many people interviewed for this report said that discriminatory treatment still poses a serious obstacle to testing and treatment. When it comes to access to information, marginalized groups, particularly men who have sex with men, are often ignored by public outreach campaigns around HIV/AIDS.

The Strategic Framework pledges to “build partnerships between government and CSOs [civil society organizations] and other agencies working with vulnerable populations to advocate for their empowerment and protection.” The government has, through its health agencies, supported several outreach programs implemented by CSOs and other non-governmental organizations (NGOs) targeting key populations. But the best representatives of vulnerable populations’ needs are membership organizations composed of those populations themselves – and in a context where men who have sex with men, sex workers, and people who use drugs face a constant threat of violence at the hands of police and other state actors, including torture and rape, it is difficult to speak of a “partnership” between these groups and the government.

MSM and sex worker activists told us that they were not aware of any efforts by government health agencies to advocate for decriminalization of same-sex conduct or sex work since the Strategic Framework was published, despite its commitment to “acknowledge the vulnerability of sex workers and men who have sex with men and advocate for their access to HIV preventive information and services and for decriminalization of their activities.” In early 2013, a government health official informed Human Rights Watch that his agency was beginning to reach out to police, with hopes of initiating discussions on decriminalization. But no further concrete advocacy initiatives – which would ultimately have to include lawmakers, not just police – had been undertaken. This may be due, in part, to some public officials’ lack of awareness of the Strategic Framework’s content in English: Human Rights Watch discovered that where the English version calls for “decriminalization of their activities,” the Kiswahili version only calls for “not scorning their activities” (kutokudharau shughuli zao).

A Holistic, Rights-Based Approach to HIV/AIDS

If Tanzania is truly committed to addressing HIV/AIDS among key populations, it should do so holistically. Institutions in the public eye, such as police and the health sector, should provide protection and treatment to at-risk groups, modeling positive behavior to other Tanzanians, rather than setting an example of hatred and bigotry.

Tanzanian laws and practices toward men who have sex with men, sex workers, and people who use drugs do not only prevent full realization of Tanzania’s commitment to stamp out HIV, they also violate international law. The criminalization of voluntary, consensual sexual relations amongadults is incompatible with respect for a number of internationally recognized human rights, including the rights to privacy and non-discrimination. Criminalization of the voluntary, commercial exchange of sexual services, as in the case of consensual sex work by adults, is also incompatible with the right to privacy, including personal autonomy. Human rights violations also often accompany enforcement of both sets of criminal laws, and enforcement of criminal laws against drug use and possession for personal use.

Human Rights Watch and WASO call on Tanzania to uphold human rights for all people, including marginalized groups. The Criminal Code should reflect principles of equality, rather than cementing discrimination into law. State agents’ actions should consistently reflect an understanding that LGBTI people (including men who have sex with men), sex workers, and people who use drugs are entitled to the full spectrum of rights enjoyed by other Tanzanians.

There is a clear link between human rights and the public health imperative to reduce HIV infections and treat existing ones. Ending discrimination and abuse against key populations is both a public health imperative, and a question of basic human dignity.

Key Recommendations

To President Kikwete

- Publicly call for an end to police abuse, discrimination in the health care sector, and all other forms of discrimination against sex workers, people who use drugs, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex people.

To the Government of the United Republic of Tanzania

- Establish an independent civilian policing oversight authority mandated to receive complaints regarding police misconduct, carry out investigations, and refer such complaints to prosecutors.

To the Parliaments of Tanzania and Zanzibar

- Begin decriminalizing consensual sexual activity between adults, including same-sex conduct and consensual adult sex work. Also review laws on personal drug consumption and possession in order to ensure they are consistent with public health and human rights imperatives.

To the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare of the Republic of Tanzania, Ministry of Health of Zanzibar, and all Government Institutions Working on HIV/AIDS

- Issue orders to health workers that discrimination against members of marginalized groups will not be tolerated, and conduct trainings and inspections to ensure this order is followed.

To the Tanzania Police and Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions

- Issue orders to all police that no crime victim should be denied assistance, arrested, or harassed on the basis of their sexual orientation or gender identity, or their status as a sex worker or drug user. Publicly announce that members of at-risk populations can report crimes without facing the risk of arrest, and establish police liaisons to these communities.

To Donor Governments and Institutions Supporting HIV/AIDS Programs or Human Rights Programs in Tanzania

- Support the development of membership organizations among sex workers, LGBTI people, and people who use drugs, such that these persons can have collective institutional voices.

- Ensure that funding directed to HIV/AIDS in Tanzania includes funds specifically aimed at key populations’ health needs.

Methodology

This report is a collaboration between Human Rights Watch and the Wake Up and Step Forward Coalition (WASO), a coalition of organizations serving men who have sex with men (MSM) in Dar es Salaam. The Tanzania Gender Networking Program (TGNP) and the Nyerere Centre for Human Rights, both based in Dar es Salaam, also helped to conceive and research this report.

Between May 2012 and April 2013, Human Rights Watch and WASO conducted field research in Dar es Salaam, Zanzibar, Tanga, Arusha, and Mwanza. Human Rights Watch conducted additional research in Mbeya and Chunya with the assistance of Population Services International (PSI), an international NGO focusing on reproductive and sexual health.

Two Human Rights Watch researchers and two WASO researchers interviewed 254 people for this report, including 121 members of key populations:

- 47 men who have sex with men (14 of whom also engaged in sex work, either occasionally or as a full-time occupation)

- 3 transgender people (two male-to-female and one female-to-male)

- 39 adult women sex workers

- 13 girls under 18 engaged in sex work

- 19 people who inject drugs, 5 of them female

Interviewers asked young women and girls engaged in sex work to state their own ages in order to determine which of them were children. In Tanzania, many people do not have birth certificates so exact age can be difficult to determine.

We also spoke with other members of vulnerable populations that are not necessarily considered most at-risk, including nine lesbians or women who have sex with women (WSW), one of whom was also a sex worker, and one of whom also identified as intersex; 13 people who use non-injection drugs; and 12 people who formerly used drugs.

Most interview subjects were approached with the assistance of local or international NGOs. In some cases, particularly where we could find no organizations working with female sex workers, we approached female sex workers in bars or in the street to request interviews with them.

In locations outside Dar es Salaam and Zanzibar, it was difficult to identify and interview members of key populations, in part because of a near-total absence of local organizations that liaise with them. Our two- to four-day visits to mid-size towns, where same-sex intimacy and other socially controversial issues are rarely discussed openly, did not allow sufficient time to gain the trust of a significant number of LGBTI people, sex workers, and people who use drugs. Due to this limitation, and the greater amount of time we spent conducting interviews in Dar es Salaam, this report includes many more case studies from Dar es Salaam compared to other parts of the country. Further research into the specific situations facing key populations in other parts of the country would be beneficial for stakeholders seeking to develop interventions that address their needs.

In each location, we spoke with local and international NGOs, specifically those engaged on issues such as HIV education and outreach, gender equality, and harm reduction.

We also interviewed officials from the government, including from the police; the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare; the Ministry of Gender, Youth, and Community Development; and the Preventing and Combating Corruption Bureau, as well as members of government commissions addressing human rights, HIV/AIDS, and drugs. We also interviewed academics at Muhimbili University and the University of Dar es Salaam who are conducting research on HIV among key populations.

Interviews were conducted in English and Kiswahili by researchers and a consultant fluent in those languages. Interview subjects who traveled to meet with us, generally on public buses, were reimbursed for transport and lunch, up to Tsh 5,000 ($3) depending on the distance traveled. All interview subjects consented to take part in our interviews, which they were informed would be included in a human rights report.

The names of most interview subjects from key population groups have been withheld to assure their anonymity. Each has been assigned a first name and an initial that bear no relation to their real name.

I. Background

HIV in Tanzania: High Prevalence amongst Key Populations

KEY DATES |

|

|

1983 |

First AIDS cases documented in mainland Tanzania.[2] |

|

1980s, early 90s |

HIV prevalence escalates rapidly. |

|

1996 |

AIDS epidemic peaks: 8.4 percent of the population aged 15-49 is infected with HIV.[3] |

|

1988 |

National AIDS Control Programme (NACP) set up to coordinate HIV/AIDS response. |

|

2001 |

Tanzania develops national AIDS policy, establishes the Tanzania Commission for AIDS (TACAIDS) to coordinate a multi-sectoral response. Rates begin to decline.[4] |

|

2007 |

Prevalence decreases to 5.8 percent.[5] |

|

2007-2012 |

Progress stagnates. |

|

2012 |

TACAIDS places prevalence at 5 percent.[6] |

A recent report by World Bank economists finds

Tanzania is falling behind other countries in the region in reducing Aids-related deaths.… The fact that so many Tanzanians still die from Aids, despite the existence of treatment, signals that the country’s health system does not reach those in need of HIV testing and therapy.[7]

Today, Tanzania ranks fourth in the world in terms of the total number of AIDS deaths.

The stagnation in reducing prevalence does not reflect lack of investment by Tanzania and its partners in the fight against HIV/AIDS. Between 2004 and 2012, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria disbursed over US$400 million to Tanzania for HIV/AIDS.[8] And between 2009 and 2011, the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) gave Tanzania over $1 billion for HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment, signing a five-year partnership agreement with Tanzania’s government in 2010 that commits both the US and the Tanzanian government to reducing new HIV infections and AIDS-related deaths.[9] According to PEPFAR, the Tanzanian government has steadily increased its expenditures on HIV/AIDS activities, and there have been notable gains in public awareness, testing, and the availability of antiretroviral therapy (ART).[10]

But the stagnation in reducing prevalence suggests that some groups are not being reached. Among those hard-to-reach groups are those who belong to what public health agencies have identified as “key populations” or “most at-risk populations” (MARPs). These populations—comprising men who have sex with men (MSM), transgender people, people who inject drugs, and commercial sex workers—are most likely to be exposed to HIV or to transmit it.[11]

Indeed, while overall HIV prevalence hovers around 5 percent on the Tanzanian mainland, some studies indicate that rates are significantly higher among MSM, sex workers, and people who inject drugs. Reliable figures on a nationwide scale are not available. However:

- HIV prevalence was 31 percent among Dar es Salaam female sex workers compared to 10 percent among women in the general population, according to a 2010 NACP study;[12]

- A staggering 70 percent of female sex workers in Mbeya were HIV positive, according to a 2001 study;[13]

- HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men in Dar es Salaam is as high as 40 percent, according to preliminary results from a recent study;[14]

- An estimated 35 percent of people who inject drugs in Dar es Salaam have HIV.[15]

In semi-autonomous Zanzibar,[16] HIV prevalence among the general population has remained low—around 0.6 percent in 2008—since the first reported AIDS cases in 1986.[17] But Zanzibar faces a concentrated epidemic, with key populations bearing the brunt. According to government estimates, 12.8 percent of female sex workers, 10.8 percent of men who have sex with men, and 16 percent of people who inject drugs have HIV.[18]

Legal and Policy Environment

Health specialists have called upon governments to acknowledge the link between human rights and the public health imperative to reduce HIV infections and treat existing ones. As UNAIDS argues, criminalization and discrimination drive key populations away from essential services:

The criminalization of people who are at higher risk of infection, such as men who have sex with men, sex workers, transgender people and people who use drugs, drives them underground and away from HIV services. This increases their vulnerability to HIV, as well as to stigma, discrimination, marginalization and violence.[19]

The Global Commission on HIV and the Law, a commission of experts that the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) established in 2010, also calls for decriminalizing sex work and same-sex conduct.[20] Even Zanzibar’s own National HIV Strategic Plan II recognizes the barriers erected by discriminatory laws and policies:

Discriminatory laws, and both unhelpful policies and regulatory frameworks, have had a negative bearing on some of the key sub populations limiting their access to services.[21]

However, Tanzania criminalizes the activities of all three groups. Consensual “carnal knowledge against the order of nature” is punishable in mainland Tanzania by a minimum of 30 years and a maximum of life in prison, [22] while “gross indecency” between males is punishable by five years in prison. [23] In Zanzibar, the law prohibits consensual same-sex relations between men (with a 14-year penalty) and women (with a 5-year penalty). [24] Zanzibar also criminalizes undefined “unions” between couples of the same sex. [25] The laws prohibiting same-sex conduct are rarely enforced, but do serve to drive LGBTI people underground.

Engaging in sex work is illegal in both mainland Tanzania and in Zanzibar, and sex workers are frequently arrested in both places.[26] Tanzania’s penal code punishes with three months in prison “loitering or soliciting in a public place for the purposes of prostitution.”[27] Zanzibar’s penal code is harsher, stating, “Any person who for consideration offers her or his body for sexual intercourse commits an offence and shall on conviction be liable to imprisonment for a term of three years.”[28]

Personal consumption of narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances is prohibited in both the mainland and in Zanzibar, with sentences ranging from seven to ten years.[29] A 2009 Zanzibar law allowed for an alternative sentence by which first-time offenders convicted of possessing a small quantity of drugs for personal consumption may be sentenced to six months in an education center followed by treatment at a rehabilitation center.[30] The law was modified in 2011, replacing the education center option with six months in prison.[31]

Tanzania’s Second National Multi-sectoral Strategic Framework on HIV and AIDS lists, as one strategy to reduce prevalence among vulnerable groups, “To acknowledge the vulnerability of sex workers and men who have sex with men and advocate … for decriminalization of their activities.”[32] But Tanzanian lawmakers have not engaged in serious discussion about decriminalizing same-sex conduct or sex work.

A former health official in Arusha, in northern Tanzania, confirmed that the criminalization of same-sex conduct made it more difficult to reach MSM in public health campaigns:

There is no specific program here for MARPs… it’s very difficult for the medical authorities to find them. We know they exist, but how can you access them when it’s illegal? If it were a legal activity, maybe it wouldn’t be difficult.[33]

Criminalization also complicates outreach by NGOs. The representative of an Arusha-based organization that conducts sensitizations on HIV and safer sex told Human Rights Watch and WASO that she had thought about trying to reach out to men who have sex with men, but had been afraid to do so, thinking that it was illegal to conduct workshops for MSM and that she would run into problems with the government.[34]

Mistrust of state officials—a result of both criminal laws and abusive practices—constitutes an obstacle to outreach work. In Zanzibar, a representative of the HIV/AIDS organization ZAYEDESA explained:

The police are a problem. In our HIV prevention work we had to convince them [key populations] that we’re not coming with the police to arrest them. [35]

In Mwanza, a representative of a local HIV/AIDS organization working with people who use drugs told Human Rights Watch, “We have to build trust with them, to explain that we are not from the government.”[36] Similarly, a representative of an international NGO seeking to do HIV outreach with sex workers in Mwanza said, “There is a need to sit and address some of the issues relevant to them. They need to know you, to build trust. They may think we want to chase them from this town.”[37]

Dr. Joyce Nyoni, a lecturer at the University of Dar es Salaam who is carrying out research among men who have sex with men, told Human Rights Watch that criminalization complicates academic research on key populations:

Because [same sex conduct] is illegal, it’s more difficult for us to do outreach and sensitization. It would be easier to find a platform to do so if it were legal. People are afraid to come to us. Just for doing the research I had an office outside the university. We had to do things in a low-key way, not have groups come…

The main challenge is, how do we reach them? It’s more difficult now with SIM cards being registered. They [the government] can track people. We were giving messages by cell phone about HIV/AIDS and condom use, to correct misinformation. Some thought condoms don’t prevent HIV/AIDS, or that anal sex doesn’t spread HIV/AIDS. It could be harder to do this programing now. [38]

Criminalization also gives other government bodies an excuse to devote inadequate attention to key populations. An official at the Commission on Human Rights and Good Governance (CHRAGG), Tanzania’s national human rights institution, told Human Rights Watch that the commission does not address rights abuses against LGBTI people. According to the official, “It’s sensitive, no one wants to talk about it. As a government institution, we can’t do it. It would be against the framework that is in place. It’s a criminal case.”

Despite having conducted no research on the subject, the CHRAGG official assured Human Rights Watch that key populations are nonetheless “not harassed or discriminated against.” [39]

Access to Information

Public health campaigns around HIV in Tanzania largely target heterosexual couples. In a study on condom use among MSM, the key researchers noted, “Almost no HIV prevention materials in Tanzania are written with MSM mentioned…. There is an urgent need for MSM-relevant and accessible HIV prevention materials.” The researchers attribute this information gap to the law that criminalizes sex between men, as well as to a social context “where MSM are almost universally denigrated.”[40]

The information gap contributes to ignorance on the part of some of the people most vulnerable to HIV. Dr. M.T. Leshabari, a public health professor at Muhimbili University, said he had encountered many misconceptions about HIV among MSM:

Some believe anal sex is not a form of transmission, because in popular sensitization campaigns in Tanzania, it’s sex between a man and a woman that is portrayed as a form of transmission. Some believe the anus is hot and can kill the virus; some believe they can flush it out afterwards. There is nothing specific for MSM in terms of public awareness campaigns.[41]

Human Rights Watch and WASO’s research also found evidence of these misperceptions. Daudi L., a gay man in Mwanza, told Human Rights Watch and WASO that he did not know HIV could be spread through anal sex.[42] Kashif M. told us he does not consider himself gay, but had anal sex with a man on one occasion, with no awareness of the risks:

I had sexual relations with a guy the other day. He wanted me to have sex with him, so I did it. I did not use a condom. I did not know you could get AIDS from anal sex.[43]

The Second National Multi-sectoral Strategic Framework on HIV and AIDS calls for collaboration between government and civil society groups representing key populations, but men who have sex with men, people who use drugs, and sex workers have few organizations that directly represent them, and are often excluded from public debates about issues that directly concern them.

As far as Human Rights Watch and WASO could ascertain, LGBTI organizations exist only in Dar es Salaam and Zanzibar. These organizations cannot operate with complete openness, as they are afraid of being shut down by the government, but they have established working relationships with government health institutions such as TACAIDS and the Zanzibar AIDS Commission. There are no harm reduction programs for people who use drugs outside of Dar es Salaam. There is currently no organization of any kind working with sex workers in Arusha, a tourist hub, despite the sizable sex worker population there.[44] While sex worker organizations exist in Dar es Salaam, none of them have even attempted to register with the government.

As noted above, some mainstream human rights organizations hesitate to reach out to key populations out of fear that programming for these marginalized groups may be illegal. The criminalization of key populations poses a challenge to human rights defenders. For the small but burgeoning community of self-identified human rights defenders in Tanzania, a lack of clarity regarding the legality of work with LGBTI people and sex workers—combined with intolerant attitudes on the part of some human rights defenders—poses a barrier to collaboration between LGBTI and sex worker activists and mainstream human rights groups. One human rights activist told Human Rights Watch that if the government were to demonstrate greater tolerance toward LGBTI people and sex workers, his network would feel safer in reaching out to marginalized groups and collaborating with them on addressing basic human rights violations, including arbitrary arrests, torture, and denial of access to health care and justice.[45]

Ujamaa and ExclusionUnder Tanzania’s first president, Julius Nyerere (1961-1985), Tanzania developed a unique ideology of African socialism, known as Ujamaa—Kiswahili for “relationship, kin, or brotherhood.” Nyerere’s Ujamaa was a socialist philosophy of development, said to be based on principles of freedom, equality, and unity. Nyerere established Kiswahili as the national language to promote national identity and prevent ethnic conflict. Tanzania’s constitution includes strong language on non-discrimination, human dignity, and the eradication of all forms of discrimination and injustice (see Section VII for citations). The model of national unity and non-discrimination has, in many regards, been effective. Tanzania is the only East African country that has not suffered vicious cycles of ethnic and political violence. For a country with large Christian and Muslim populations, religiously motivated violence is rare, although recent attacks on churches have raised concerns. [46] But Tanzania is not free from social exclusion. Due to either their immutable characteristics or their general social status, there have always been outsiders in Tanzania. In recent decades, “outcasts” have included groups such as people with albinism, refugees, and street children. [47] Further, an overstated emphasis on social cohesion has not always been good for human rights in Tanzania. A ruling party member of parliament (MP) told a journalist in 2012 following a wave of opposition protests, several of which the police shut down, “This is a country where consensus is valued—calm and peace is a big deal. Law enforcement authorities probably need to learn how to deal with this [new] kind of expression.”[48] Under an enforced veneer of unity, discussion of human rights can seem provocative. One Dar es Salaam-based activist explained, “There were no human rights organizations before because of the community system…. When we started to talk about human rights, for many in Tanzania, it was a strange thing.”[49] Discussion about the rights of marginalized groups, such as LGBTI people, sex workers, or people who use drugs, is considered especially sensitive.[50] The HIV crisis has to some extent brought these groups into the spotlight, with government ministries for the first time recognizing them as vulnerable to HIV infection and particularly marginalized within Tanzanian society. But most rhetoric around “key populations” in Tanzania has focused exclusively on access to HIV services and health care. |

II. Social and Legal Context for Abuses against LGBTI People, Sex Workers, People Who Use Drugs

The three key populations addressed in this report face a similar array of human rights abuses. This section provides an overview of the particular ways in which the law, discriminatory application of the law, and social stigma combine to reinforce the marginalization of each group. The three stories highlighted in text boxes demonstrate how members of marginalized groups are victims of multiple, compounded violations.

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Intersex (LGBTI) People

Tanzania has one of the most stringent anti-homosexuality laws in the world, with penalties in the mainland of 30 years to life in prison for consensual sex between men.[51] The legal provisions that criminalize same-sex conduct are based on a British colonial law, which provided for 14-year prison sentences for “carnal knowledge against the order of nature.”[52] The sentence was revised in 1998 and again in 2002, and is now the second most draconian anti-homosexuality law in East Africa after Uganda’s law, which mandates a life sentence for same-sex conduct.[53] Zanzibar’s law, as noted, does not criminalize just sexual relations, but also undefined “unions” between same-sex partners.

The status of LGBTI people in Tanzania was rarely discussed openly until the last decade, and the initiation of public discussion on the subject has met with backlash. In 2003, about 300 Tanzanians protested a planned visit to Dar es Salaam by a gay tour group from the United States. The visit was subsequently canceled.[54] In 2007, a Tanzanian bishop came under fire for proposing further dialogue about homosexuality in the community and the church.[55] In September 2011, the Gender Festival—an event bringing together gender activists from throughout Africa since 1996 and organized by the Tanzania Gender Networking Programme (TGNP) and the Feminist Activist Network, two Tanzanian NGOs—became a flashpoint for heated debate on sexual rights and whether same-sex conduct was “natural.” Participants who self-identified as LGBTI were chased by media and forced to flee the premises, and then attacked by members of the public.[56] According to one gay participant, “[A] mob had gathered there saying they wanted to kill gays. I was getting into a dala dala [public minibus] and the conductor started to beat me. Then everyone started beating me.” A popular TV anchor rescued him and drove him to the hospital.[57]

The events contributed to heightened backlash from certain media and social networking sites, and the “outing” of MSM participants affected their relationships with families, employers, and landlords. Participants told Human Rights Watch that at least six MSM lost their jobs or were forced to change their residence after the festival, some because they had been seen on television, others simply because the debate provoked by the Gender Festival led to a witch hunt in which suspected gays were publicly accused by family members, neighbors, and employers.[58]

In October 2011, the United Nations Human Rights Council held its Universal Periodic Review (UPR) of Tanzania.[59] During the UPR, Tanzania refused to accept all three recommendations from fellow UN members related to sexual rights: to take steps to protect the rights of all persons irrespective of their sexual orientation, to adopt anti-discrimination legislation, and to decriminalize consensual same-sex conduct.[60]

In November 2011, Tanzanian officials responded critically to comments by British Prime Minister David Cameron to the effect that a country’s record on LGBTI rights would play a role in British foreign aid determination. While donor countries linking human rights to aid is not a new concept, the specific mention of human rights for LGBTI people produced a backlash. A Tanzanian daily newspaper reported Foreign Minister Bernard Membe as saying, “Our position on this matter is crystal clear. Our moral values and culture will always prevail even if we remained poor.”[61] The paper offered its own opinion, arguing that homosexuality is

[A] cardinal sin that smells to high Heaven [which] can only happen in a rabid world where lunatic men and scarlet women have no qualms about flouting the tenets established societal customs or offending Almighty God.[62]

Against this backdrop, arrests, violence, and harassment of LGBTI people are common, particularly for MSM.[63] Examples of discrimination in housing, education and employment have also been reported and affect lesbians and bisexual women as well as gay and bisexual men.[64]

Discrimination against sexual and gender minorities is partly rooted in a misunderstanding of homosexuality as something one “does,” not something one “is.” A representative of a local NGO in Tanga, while emphasizing the importance of providing services to LGBTI people, said being gay is “a business,” conflating male homosexuality with sex work—reflecting a common assumption throughout Tanzania.[65] This belief contributes to homophobia even among those working in fields such public health and human rights: in an interview with Human Rights Watch, the regional manager of a well-respected international public health organization called for “killing the gays” in order to prevent others from “becoming members.”[66]

While discrimination occurs at many levels, one gay man blamed the lack of positive leadership at the highest level of government: “The president doesn’t promote the rights of LGBT people. When he does—one day when he says ‘These people have equal rights’— people will stop abusing us.”[67] Abdalla J., a 32-year-old gay man whose father expelled him from the family home after he attended the 2011 Gender Festival, blamed Tanzania’s anti-homosexuality law: “You should tell the government to decriminalize us. What I do is my personal life. I don’t know who it affects but me.”[68] A gay man in Tanga expressed a simple wish: “I just want the government to treat us like human beings.”[69]

Transgender and Intersex People

LGBTI organizations working in Tanzania were only aware of a few cases of individuals who identify as transgender or who publicly present a non-normative gender expression. Of the three transgender Tanzanians Human Rights Watch and WASO were able to identify and interview in the course of this research, two had experienced human rights abuses at the hands of the police, documented in Section III.[70]

Human Rights Watch interviewed one intersex person in Tanzania (see Glossary). The concept of “intersex” is even less understood in Tanzania than that of being transgender, and it is likely that many intersex people “pass” as one gender identity or the other. However, the many documented cases of discriminatory treatment on the basis of sexual orientation in the Tanzanian health care system suggest intersex people may experience discrimination as well.

No research has been published on HIV among transgender or intersex people in Tanzania. In other countries, stigma against transgender and intersex people has been found to significantly impede prevention and treatment efforts.[71]

SAIDI W.’S STORYSaidi W., a 20-year-old gay university student who sometimes does sex work to support himself, told the following story: In December [2011], I was in a place where I look for clients. I met a client, but [it turned out] it was not a normal person, it was a police officer. We went to a guest house. The client said, “Take off your clothes.” I took off my clothes and suddenly the man pointed a pistol at me. Suddenly the guy had a tape recorder and a video camera. He said “You will be an example for others. I am from CID [Criminal Investigation Department] and I’m looking for people like you.” He took me to Central Police Station and put me in lock-up. The police there told me, “Call your fellow gays. We are going to a bar.” They were asking for gays in general, not just sex workers. They were five police. They gave me their phone and said, “Call your friends, tell them there is a party here, so there are a lot of drinks.” They were threatening to shoot me if I didn’t call my friends. They had SMG [submachine] guns. They cocked the guns at me, saying, “If you don’t call your friends, we’ll shoot you.” We went together to Sun Cillo Club in Sinza. The police put out a lot of drinks. I called five friends. All of them came. Some of them were in skirts, some were wearing make-up. Police came and put them in the Defender [police vehicle]. They said, “We’re arresting you because you’re gays and you’re shaming us. Our country does not allow homosexuals. Our law and our religion and customs don’t allow this.” They beat all of us a lot in the bar. They beat us with our belts. The bar owner and others didn’t help us—they laughed, they were happy that this was happening. The police undressed us and started to beat us with sticks. They beat us everywhere on the body. They took us to the lock-up at Central Police Station. They were calling us mashoga [derogatory term for gay] while beating us—“You are gay, why are you selling your body?” We were in the police station for four days. The other detainees gave us problems. On the fourth day, those guys decided to rape us. They didn’t use condoms. We refused, but they were bigger and older than us and used force. We called to the police and screamed for help, saying, “These guys are forcing us to have sex with them.” But the police said, “That is good, that’s what you want.” So the police were encouraging the guys in there. There were about 50 other detainees, and five of them were raping us. Three of them raped me personally. I got a lot of pain. The following day, the five men were taken to Sitakishari Police Station. A female police officer interrogated them, and seemed sympathetic when they said they had been raped: “She said, ‘Wait until tomorrow, we’ll go to the hospital.’ She gave us her phone to tell us to call a relative to come for bail.” Saidi called his mother, who came in to meet the officer. However, despite the officer’s sympathetic attitude, she wanted her cut: [The officer] wanted money as a bribe to let us free and end the case. The police were asking Tsh 500,000 (about $307) for all five. My mother cried a lot, saying, “I don’t have money.” I said, “Mom, this case is really bad.” My mother managed to get Tsh 400,000 after three more days [from] someone who loans money. After bribing the police, we were released…. It took a long time for my mom to pay that money back. Saidi concluded: “When I remember that situation I want to cry.”[72] |

Sex Work and Commercial Sexual Exploitation

Although sex work is illegal in Tanzania, it takes place openly in many cities and towns, with sex workers gathering at well-known locations. While they are occasionally prosecuted and serve prison sentences, sex workers are often simply beaten or raped by police and then return to the streets, as documented in Section III.

A recent World Bank-funded study describes “addressing violence, stigma and discrimination against sex workers” as “a human rights imperative.”[73] According to the study,

Criminalization enables police to perpetrate abuse and humiliation, demand free sexual services, and extort fines from sex workers with impunity, and renders those who suffer violence and other human rights abuses with little legal recourse…. By driving sex work underground, criminalization is also counterproductive to community mobilization efforts to strengthen sex workers rights and promote autonomy.[74]

These impacts of criminalization are manifest in Tanzania. Sex workers who suffer violence, at the hands of both police and civilians, rarely report the crimes against them. A National AIDS Control Programme study of sex workers in Dar es Salaam found that 33.3 percent reported being beaten by their clients.[75] A representative of an international public health organization in Mwanza explained, “Sex workers do not have a place to speak against injustices done to them, and the police can take advantage of them if they go and report. If they go to the police, the police just become their customers for that night.”[76]

Both adults and children engaged in sex work are regularly forced into sex without condoms, including by police officers. As a sex worker in a small mining village put it: “Some men have knives, and if you want to use a condom, they threaten to kill you. This happened to me here in Itumbi. I decided to have sex without a condom because I was afraid. All the men here carry knives.”[77] In Dar es Salaam, while NACP found high levels of reported condom use among sex workers, it also found that “the high prevalence of sexual and physical abuse by partners indicates that FSWs [female sex workers] may not be able to make protective choices.”[78]

Many sex workers mistrust public hospitals, where they risk being refused service or stigmatized, as seen below. NACP found that while most female sex workers in their study had been tested at least once for HIV, “Access to services and HIV testing were not as routine or frequent as is recommended for members of high-risk groups.”[79]

Sexual Exploitation of Children

A particularly vulnerable group comprises children who are sexually exploited through sex work. Girls engaged in sex work, or otherwise sexually exploited, are significantly more likely to experience sexual, physical, and emotional violence, according to a national study on violence against children in Tanzania.[80]

International law strictly prohibits commercial sexual exploitation of children.[81]Any child who is engaged in sex work or otherwise commercially sexually exploited should not be prosecuted or penalized for having been party to illegal sex work but should be provided all appropriate assistance. The use of children in sex work is punishable by a prison term of up to 20 years under Tanzanian law.[82] However in several cases that Human Rights Watch and WASO documented, police physically and sexually abused children engaged in sex work, rather than protect them. According to the US State Department, no one was prosecuted in Tanzania in 2012 for sexual exploitation of children.[83]

ROSEMARY I.’S STORYRosemary I., an orphan, started sex work when she was 10. When Human Rights Watch interviewed her in Mbeya, she was 14 and had a one-year-old child. She was expelled from school in Form 3 after becoming pregnant.[84] Rosemary sees little opportunity for herself beyond earning money through sex work. Rosemary is a child under international and Tanzanian law, but to the Tanzanian police, she is also a criminal. She is also easy prey for sexual predators within the police force. She has been raped by police “about seven times” by her calculations. She explained, “When they catch you, they don’t send you to the police station. Wherever they meet you, they could take you to the toilets in the club, or if they meet you in the road, they just find a hidden place and have sex with you there. They don’t use condoms—they always refuse.” Refusing sex with police is not an option for most sex workers we interviewed. In December 2010, when Rosemary was 12, she was arrested while working in Tunduma, near the Zambian border. The police asked for sex, and she refused. She told Human Rights Watch, One time I refused and they sent me to [Tunduma] police station. I asked for forgiveness when I reached the station. They were four or five cops. They said, “If you want forgiveness, you have to sleep with us.” So I slept with all of them, because all of them wanted it. After I slept with them all, they let me go. The same month, Rosemary was beaten and raped by another set of police officers, again at Tunduma police station: Once I was beaten on the road and sent to the police station. They were beating me with the thick sticks they carry. They beat me on the head, on the arms. When I arrived at the station, I was in pain and bleeding from the nose. Other police there said, “We have to have sex with you if you want us to release you.” In April 2011, Rosemary was drugged by a client in Mbeya. She later deduced that the client had taken her to a guest house, vaginally and anally raped her while she was unconscious, and left her naked body outside the guest house. According to Rosemary, I woke up in the morning and found myself outside, bleeding from my private parts. People found me and wanted to send me to the hospital, but I refused because I was afraid. How was I going to explain myself? I was also afraid to go to the police because the police might just want money, and I had no money. Also, I couldn’t explain that I was selling myself because then it could be a case against me.[85] |

People Who Use Drugs

Parts of Tanzania, including Dar es Salaam, Zanzibar, and Arusha, have high levels of drug use, especially injection drug use. An estimated 25,000 to 50,000 people inject drugs in Tanzania.[86] Most are injecting heroin, which spread in the 1990s when drug smugglers switched from traditional overland routes from Asia to Europe, opting instead for transport across the Indian Ocean. Zanzibar and Dar es Salaam both became ports of entry.[87]

People who inject drugs (PWID) are particularly vulnerable to HIV/AIDS, largely because of sharing needles. Research suggests that new HIV infections among PWID in Tanzania are increasing. [88]

To address high HIV rates, Médecins du Monde (MdM), an international NGO, is pioneering harm reduction work among people who inject drugs in Temeke, Dar es Salaam’s poorest district. MdM runs a needle and syringe program, and has trained at least 150 police officers in Dar es Salaam on the importance of access to clean needles and syringes.[89] It is also documenting human rights abuses affecting its beneficiaries, and working with police commanders to address the cases systematically. There are no needle and syringe programs in Tanzania outside Dar es Salaam, although they have been considered in Zanzibar.[90]

Tanzanian public health officials have also introduced methadone treatment for heroin users.[91] The methadone clinic at Dar es Salaam’s Muhimbili Hospital, founded in 2011 and funded by PEPFAR, is only the second such clinic in sub-Saharan Africa.[92] A second methadone clinic in Dar es Salaam opened at Mwananyamala Hospital in 2012.

In Zanzibar, the government has begun to recognize that heroin use is widespread, and is not best addressed through punitive measures. The president of Zanzibar has spoken publicly about the need to support people who use drugs and provide them with services; according to members of the Zanzibar Drug Control Commission, the president’s statements have played a positive role in decreasing stigma by introducing non-punitive approaches into the public debate.[93]

Nonetheless, people who use drugs in Tanzania are heavily stigmatized and subjected to abuse. Dozens of those interviewed by Human Rights Watch and WASO spoke of being victims of physical violence at the hands of the police, vigilante groups, and neighbors. A number of them told us that people who use drugs are generally regarded as “thieves,” regardless of whether they have actually stolen anything.

JANUARY H.’s STORYJanuary H. lives in Temeke District and uses heroin. In 2011, he was attacked by members of a mob of Sungu Sungu—a militia group, discussed further below—who accused him of robbery. They dragged him to a nearby schoolyard, where they cut him on the head and face with pangas [machetes]. January extracted himself from the mob and ran to the Mashini ya Maji police post, where he lost consciousness. When he came to, he said, I heard the police saying [to the Sungu Sungu], “Why didn’t you kill him? Why did you bring him here?” Then a senior police officer asked “Who did he steal from?” and nobody answered. The police took me to another police station, Mtongani. They asked who the complainant was and what the R.B. [Reporting Book] number was, but there was none. When no one complained, the Mtongani police called the Chang’ombe police. They came… and took me to the hospital. January thought his travails were over, but the health workers at Temeke District Hospital who treated him only made things worse. He recounted: The doctor examined me, wrote things down, and sent me for stitches in Ward 10. There they started sewing me up without any injection [anesthesia]. I asked for it, and the nurse said, “We don’t need to. We are going to sew you without. We could inject you with poison rather than with anesthesia.” I heard them [hospital staff] saying, “That one is a thief.” So they stitched me everywhere without anesthesia. When January was discharged, he considered filing a complaint with the police against his attackers, but had second thoughts: “[For] many of us youth who use drugs, the police create obstacles to us opening cases. They might keep telling you to wait. And then later they’ll make up a fraud [fraudulent] case against you and take you to prison.” He added, with regard to the Sungu Sungu, “I know the reality is one day they’ll kill me.” [94] |

III. Police Violence, Intimidation, and Extortion

Violence, prejudice, and extortion by police contribute to severe mistrust between key populations and state institutions. For many Tanzanians, police are the face of the Tanzanian state that they encounter most regularly. For key populations, these interactions are anything but positive. Human Rights Watch and WASO documented cases of violent assault by the police against all three groups that are the focus of this report: LGBTI people, people who use drugs, and sex workers. Police also targeted children who were victims of commercial sexual exploitation. Of those who had not experienced assault, nearly everyone had experienced extortion for money, sexual favors, or both.

Among all three key populations, our research suggests that those who are the most vulnerable to police abuse are from lower socioeconomic classes. Men who have sex with men, people who use drugs, and sex workers from secure economic backgrounds often manage to avoid the police. A heroin user from a middle-class family told Human Rights Watch he was never caught by police because he used drugs in the privacy of his own home.[95] Similarly, a group of sex workers in Arusha said that because they were working in an enclosed bar frequented by a middle-class clientele, they were relatively protected from police harassment, whereas their colleagues who worked the streets were more frequently arrested and beaten.[96] While police abuse of male sex workers is common, Human Rights Watch and WASO heard of no cases in which their clients, generally well-off men, were arrested or ill-treated by police. Wealthier individuals’ ability to pay bribes also helped them, in some cases, to escape detention and violence.

Marginalized groups are not the only ones who suffer violence and abuse at the hands of the Tanzanian police. The Legal and Human Rights Centre (LHRC), an NGO, reports that the Tanzanian police extra-judicially executed at least 11 people in 2012.[97] LHRC cited a culture of impunity and the lack of an external, independent oversight body as explanations for high levels of police violence against civilians.[98]

Police corruption is also a widespread problem in Tanzania.[99] According to a representative of a foreign aid agency that works with the Tanzanian police, “Police are worse on corruption than other institutions. They may also be the worst institution on human rights.”[100] Tanzanian police regularly shake down civilians for bribes. This may include for instance, drivers, whether they do or do not break the law; victims of crime, who are seeking police assistance and are told it only comes at a price; refugees or asylum seekers who are caught without proper documentation; or people involved in unlawful sexual conduct or drug consumption.[101] Police know that the latter group is an easy target, as members of marginalized groups are less likely to file complaints.

Some efforts have been undertaken to combat police corruption. Police told Human Rights Watch that 47 officers were dismissed due to corruption in the first half of 2012.[102] However, vulnerable groups are particularly unlikely to report corrupt or violent police, as the stories below demonstrate.

Torture and Ill-Treatment

Human Rights Watch and WASO interviewed dozens of members of key populations that had been tortured, raped, ill-treated, or coerced into paying bribes by police in the last several years. In none of these cases were police held accountable for the abuses.

In Temeke, a Dar es Salaam district with high levels of drug use, victims frequently referred to a police officer nicknamed “Tyson,” based at Chang’ombe Police Station, who by all accounts seemed to draw sadistic pleasure from assaulting and humiliating people who use drugs. In one such case, Suleiman R. was arrested on December 31, 2011, and taken to Chang’ombe Police Station. There had been three robberies the previous week, and since Suleiman was known to inject drugs, police suspected him. He said,

They took me to a special room to torture me and get me to confess to the cases…. First they hit me with iron bars on the right arm. Then they took a clothes iron and ironed me on the arm. They ironed me two times. One of them was Tyson, who is also known as Adnan.[103]

Human Rights Watch saw burn marks on Suleiman’s arm consistent with those that might be left by an iron. The following day, Suleiman’s parents paid a bribe of Tsh 200,000 (about $123) in order to have him released.

Zeitoun Y. was arrested in January 2009 just after smoking heroin in his maskani.[104] He tried to run away; when police caught him, he said, “I was tied around the neck with a rope. I was dragged about 200 meters. Tyson put the rope on me and dragged me personally.” Zeitoun was taken to Chang’ombe Police Station, where he said police beat him and tried to make him confess to a robbery.[105]

Mwajuma P. reported that in 2011, Tyson beat and humiliated a group of women who use drugs:

He came to a maskani with two other police, rounded us up, and forced us to pray…. He told us to put our hands on our heads. Then he made us walk to the police and sing songs: “Us, we are drug users. Us, we steal phones.” Tyson started treating us like cows, beating us with a five-foot long heavy plastic pipe. He came with it. He beat me on the back, on the legs.[106]

Tyson forced the women to walk more than four kilometers in the hot, midday sun, according to Mwajuma. At Chang’ombe station, police took their statements. Mwajuma was released without charge after two days, when her sister-in-law paid Tsh 20,000 (about $12).

Ally H., who uses heroin, said that police from Chang’ombe beat him and his wife in August 2012:

The police came from Chang’ombe at about 8 p.m. They kicked in the door by force. They came in and started to beat me and my wife.... They were suspecting us of being drug sellers. They didn’t have any warrant. They were about seven police.

I was beaten with a rungu [club] on the knees and forearms and back. I still have pain on my knees. They hit me on the back with a stick that was like a thick branch. [107]

At the station, Ally said, an investigating officer ordered him to lie down on the floor, and different police beat him. Even after Ally paid a bribe of Tsh 40,000, he said, police “continued beating us with sticks while chasing us out of the police station. It was afternoon, and all the other police officers saw.” [108] Approximately a month after his release, a Human Rights Watch researcher observed bruises on Ally’s back that were consistent with being beaten by sticks.

Several victims also cited police from Dar es Salaam’s Oysterbay Police Station as being responsible for assault, sexual exploitation, and extortion. Fazila Y. said police from Oysterbay Police Station beat her in the middle of the street when she was caught in the maskani in October 2011 using drugs with friends:

Passers-by and shopkeepers looked on as the police kicked me, verbally assaulted me, and tore my clothes. After they were satisfied that I was hurt to their liking, they dragged me into the back of the police car. [109]

Asked whether she considered filing a complaint against the officers who beat her, Fazila said, “I do not see the point of complaining about treatment that we receive from police. What will change? Who will listen?” [110]

A police sergeant arrested and beat Mickdad J., in Tandika, Dar es Salaam, in June 2012 because he was carrying unused syringes from Médecins du Monde’s (MdM) harm reduction program:

I was coming from MdM with syringes, yellow boxes [for disposal of sharps], things that I use to inject. I was outside my home arranging these things. The sergeant saw me, stopped and arrested me. I wanted to call MdM, but [the sergeant] took me to Mamboleyo Police Post. There, he beat me with his hands, a stick, and also with his police boots.[111]

Mickdad’s mother came to the police post and paid Tsh 30,000 (about $18) to have him released, but the experience had a lasting impact due to his fragile health, Mickdad said, “Even now I have pain in my spinal cord and my coordination is not good. I am HIV positive, so when people beat me it’s a problem.”[112]

One particularly horrific case of alleged police abuse involved John Elias (his real name), a heroin user in the Kigamboni area of Dar es Salaam. On February 18, 2010, he was arrested in a drug bust in Kurasini neighborhood. According to Elias, one of the police officers involved in the arrest had a personal problem with him: the officer believed Elias was having an affair with his girlfriend. The officer seemingly used the drug bust, and Elias’s vulnerable status, as an opportunity to get revenge.

Elias told Human Rights Watch that police burst into the house at 4 p.m. and said they were conducting an operation to look for drugs:

They looked but found nothing. They arrested three of us. I was arrested by a policeman called James who suspected me of walking with his girlfriend. He knew me from before. He suspected me of using drugs, but also walking with his woman. The other two were arrested because they were drug users. [113]

All three men were taken to Kilwa Road police station. Police began taking statements from Elias’s friends, but Elias said the Officer Commanding District (OCD)—the superior of James and other officers present—ordered that he be taken to a different police post.

I was put inside a car with chains on my hands and feet. They didn’t say why. James said, “We’re sending you to Chang’ombe to break your leg.” But they were lying—they took me to Minazini post.

They put chains on my arms and legs and pushed me down. I saw a syringe with liquid inside. James was holding it. He said, “Today is your last day to see, Mr. John.” First he injected my right eye, and then the left one. I was lying on the ground. About five police were there. They were grabbing me, holding me, stepping on me with boots…. I felt like my eyes were burning. It was so hot. [114]

At around 7 p.m., Elias said, the police returned him to Kilwa Rd Police Station and put him in lockup with his friends. Police took him directly to court in the morning. Although he told court officials what the police had done to him, he was taken directly to prison and was not taken to the hospital until a week later. [115] There, he discovered that the police had injected his eyes with acid.

Today, Elias has gaping holes where his eyes should be.