“Swept Away”

Abuses Against Sex Workers in China

Map of China

Summary

Prostitutes, as we have been calling them, should be termed “waylaid women” from now on…. We ought to show respect to this special group of people.

—Liu Shaowu, head of the Public Order Management Bureau, Public Security Ministry, December 2010

Once when I was soliciting on the street, the police just came and started beating me up…. There were five or six of them, they just beat me to a pulp.

—Xiao Jing, a sex worker interviewed in Beijing, 2011

The Chinese Center for Disease Control tested me last year. But they never told me the results. I hope I don’t have AIDS.

—Interview with Zhangping, a sex worker interviewed in Beijing, 2009

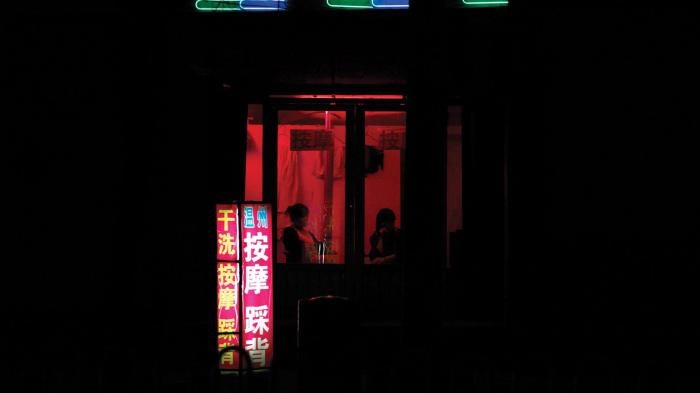

The momentous economic and social change in China in recent decades has been accompanied by a sharp increase in inequality and in the numbers of women in sex work. The United Nations, citing Chinese police sources, estimates that four to six million adult women currently engage in sex work. Although sex work is illegal in China, it is ubiquitous, present not only in large cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou, but also in smaller cities and towns down to the smallest townships in remote rural areas. Sex workers typically work from karaoke bars, hotels, massage parlors, and hair salons, as well as in public parks and streets.

Under Chinese law, all aspects of sex work—including solicitation, sale, and purchase of sex—are illegal. Chinese law treats most sex work-related offences as administrative violations, punishable by fines and short periods of police custody or administrative detention rather than criminal penalties. Nonetheless, for repeat offenders it allows for administrative detention of up to two years. In line with its prohibitionist public stance, the government periodically carries out vigorous nationwide crackdown campaigns called “saohuang dafei” (literally, “sweep away the yellow” [i.e. prostitution and pornography] and “strike down the illegal” [seize and destroy pornographic materials]).

Women engaging in sex work are victims of a wide range of police abuses; this report documents arbitrary arrests and detentions, physical violence, and other ill-treatment of sex workers in Beijing, and discusses the national legal framework that facilitates these abuses. Women interviewed for this report told Human Rights Watch of arbitrary fines, of possession of condoms used as evidence against them, of being detained following sex with undercover police officers, and of having almost no hope of winning remedies for rights violations by clients, bosses, or state agents. Sex workers also face high risks of sexually transmitted infections, including HIV.

While many of these practices violate Chinese law as well as international human rights law, the government is doing far too little to bring an end to the abuses or to ensure that women in sex work have access to health services. The women we spoke with reported abuse by public health agencies, especially local offices of China’s Center for Disease Control (CDC). These abuses included forced or coercive HIV testing, privacy infringements, disclosure of HIV test results to third parties, and mistreatment by health officials, all of which violate the right to health as defined under Chinese and international law.

Research for this report included more than 140 interviews with sex workers, clients, police, public health officials, academic specialists, and members of international and domestic nongovernmental organizations between 2008 and 2012. At the heart of the research were interviews with 75 women sex workers in Beijing, including 20 detailed interviews with women between the ages of 20 and 63. Because the information about uncorrected abuses in the nation’s capital—where in theory law enforcement should be strongest—track with the findings of interviews from other parts of the country, Human Rights Watch believes similar problems exist nationwide.

In our interviews, we focused on the women’s interactions with police and public health agencies, two institutions with which they have frequent, direct contact. It does not attempt to analyze the actions of all agencies relevant to regulation of prostitution, such as those providing social services or child protection, those addressing trafficking, and those that run Custody and Education centers for women. Nor does this report attempt to comprehensively analyze China’s response to trafficking in persons.

* * *

Officially considered as one of the “six evils” of society—along with gambling, superstition, drug trafficking, pornography, and trafficking of women and children—prostitution is labeled by the Chinese government as an “ugly social phenomenon” that goes against “socialist spiritual civilization.” Even though in practice Chinese authorities effectively tolerate prostitution and entertainment venues that offer prostitution services, these campaigns mobilize large numbers of law enforcement agents across the country and typically last between several weeks and a few months. In 2012 Beijing authorities initiated two campaigns, one lasting from April 20 to May 30, and another ahead of the 18th Party Congress in October and November. In the course of these campaigns, police repeatedly raided entertainment venues, hair salons, massage parlors, and other places where sex work occurs. They forced some venues to close, and detained large numbers of women suspected of being sex workers.

These highly publicized crackdowns generate a climate conducive to increased incidences of police brutality and other abuses of sex workers. Because police crackdowns drive the trade further underground, they effectively increase the vulnerability of women who engage in sex work to police and client abuse. They also induce some sex workers to engage in higher risk sexual behavior. Many sex workers, for instance, say they avoid carrying condoms during campaigns to minimize the risk of arrest. Moreover, activists told Human Rights Watch that women detained in these sweeps are rarely referred by law enforcement officials to services they may need or want, such as social services, health care, or employment or training resources.

The Chinese government, which in 2003 belatedly but comprehensively began addressing the HIV/AIDS crisis, has focused many of its HIV testing and educational programs on people who engage in sex work; official data suggest that the rate of HIV infection among sex workers nationwide ranges from 3 to 10 percent. Some of these efforts, however, entail coercive testing and violations of privacy rights. The Chinese government justifies these practices in the name of public health, but international experience has demonstrated that for HIV to be successfully curbed, populations such as sex workers must be able to obtain confidential health care without fear of harassment or discrimination.

Although sex work is illegal in China, people who engage in sex work are entitled to the same rights and freedoms as other people, including the rights to equality and non-discrimination, privacy, security of person, freedom from arbitrary detention, equality before the law, due process of law, health, and, importantly, the right to a remedy when the abovementioned rights are violated.

The imposition of punitive penalties for voluntary, consensual sexual relations amongst adults violates a number of internationally recognized human rights, including the rights to personal autonomy and privacy. Human Rights Watch takes the position that this also holds true with respect to voluntary adult commercial sex work, and that respecting consenting adults’ autonomy to choose to engage in voluntary sex work is consistent with respect for their human rights. Criminalization of sex work also creates barriers for those engaged in sex work to exercise basic rights such as availing themselves of government protection from violence, access to justice for abuses, access to essential health services as an element of the right to health, and other available services. Failure to uphold the rights of the millions of women who voluntarily engage in sex work leaves them subject to discrimination, abuse, exploitation, and undercuts public health policies.

Human Rights Watch believes the Chinese government should take immediate steps to protect the human rights of all people who engage in sex work. It should repeal the host of laws and regulations that are repressive and misused by the police, and end the practice of indiscriminate law enforcement “sweeps.” The government should also lift its sharp restrictions on the ability of civil society organizations—including sex worker organizations—to register and carry out their activities freely within the boundaries of the law. Finally, it should commit to international standards on HIV/AIDS testing, particularly with respect to privacy and informed consent.

Key Recommendations

- Enact legislation to remove criminal and administrative sanctions against voluntary, consensual adult sex work and related offenses, such as solicitation.

- End periodic mobilization campaigns to “sweep away prostitution and pornography” (saohuang dafei) that have generated widespread and severe abuses against women engaging in sex work.

- Publicly commit to strict nationwide enforcement of provisions that prohibit arbitrary arrests and detentions, police brutality, coerced confessions, and torture, and ensure swift prosecution of police officers who violate these provisions.

- Immediately end mandatory HIV/AIDS testing of sex workers, require informed consent prior to testing, inform anyone tested for HIV of the results, make appropriate counseling available before and after the test, and implement testing programs that conform with international standards.

- Initiate consultations with sex workers and relevant nongovernmental organizations to consider other legislative reforms to better protect the rights of sex workers.

Methodology

The scope of this study is necessarily limited by research constraints in China. The country remains closed to official and open research by international human rights organizations, and the Chinese government strictly limits the activities of civil society and nongovernmental organizations on a variety of subjects, particularly those related to human rights abuses.

Human Rights Watch focused its investigation on adult women who engage in sex work on the streets, in public places such as parks, and in small brothels that masquerade as massage parlors and hair salons, primarily in Beijing. These women are vulnerable to violence, abuse, and public health risks. They have limited protection from abusive police and clients because they tend to work alone or in the vicinity of only a few other sex workers. They tend to have little knowledge of their legal rights and strategies to protect their health. This subset of the sex worker population has previously been often overlooked in research on sex work in China, which tends to focus on women working as hostesses in karaoke venues (yule changsuo), as they are generally easier for researchers to access.

Research for this report included more than 140 interviews with sex workers, clients, police, public health officials, academic specialists, and members of international and domestic nongovernmental organizations between 2008 and 2012. At the heart of the research were interviews with 75 women sex workers in Beijing, including 20 detailed interviews with women between the ages of 20 and 63. All of those 20 detailed interviews were conducted in the homes of two women engaging in sex work: a small rented room and a makeshift shack in a back alley. Human Rights Watch also carried out two focus group discussions, one with a group of six women who solicit clients in public spaces, and one with a group of five women who work in hair salons and massage parlors. All of the sex workers we spoke with said they had voluntarily chosen sex work, though many had few job options and could earn significantly more money in sex work than in other jobs. None were currently in a situation that qualifies as trafficking.

The names and identifying details of those with whom we met have been withheld to protect their safety. All names of sex workers used in the report are pseudonyms. All those we interviewed were informed of the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, and the ways in which the information would be used. All interviewees provided verbal consent to be interviewed. All were informed that they could decline to answer questions or could end the interview at any time. In some cases, interviewees who traveled to attend interviews were reimbursed up to 100 yuan (US$15) for public transport and meal costs.

None of the interviewees were minors when this research was conducted. At least four had experienced commercial sexual exploitation when they were children, at ages 15 and 16. At least two of the interviewees had originally been trafficked into forced prostitution; at the time of our research, they had escaped their traffickers, and said they were selling sex voluntarily. In assessing the voluntariness of women’s decision to engage in sex work, Human Rights Watch applied the elements of the definition of trafficking set forth in the UN Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children.

Ten of the sex workers we spoke with solicited customers in public spaces. Eight of them worked in small brothels that were disguised as hair salons and massage parlors. Two of them worked in small karaoke venues but had previously worked in public parks.

Secondary sources we consulted include Chinese government documents, laws, and policies; reports from domestic NGOs, international NGOs, and international organizations; interviews with members of domestic nongovernmental organizations, international nongovernmental organizations, foreign governments, and international organizations working on issues pertaining to sex work, public health, trafficking, and human rights; news articles from Chinese and international media; and writings by Chinese and foreign academic experts on prostitution.

Male and transgender sex workers are also vulnerable to abuse, but due to research limitations this report does not address their situation.

This report also does not address Chinese government responses to children (those under 18) in situations of commercial sexual exploitation. The approaches appropriate to children, who in no way can be considered to be voluntarily engaging in sex work and in most cases should be considered trafficking victims, differ from those that should be applied to adults.

The report also does not attempt to analyze the Chinese government’s overall response to trafficking in persons, although it includes some references to legal standards and protections applicable both to individuals engaging in sex work and to trafficking victims.

I. Background

While prostitution decreased significantly in the years following the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, it reemerged with the economic liberalization reforms that began in 1978.[1] It first reappeared in the large coastal cities, and is now widespread in urban and rural areas throughout China.[2]

There are no exact figures on the number of people who engage in sex work in China.[3] Estimates of the number of women sex workers from the past decade range from one million to ten million.[4] The United Nations Theme Group on HIV/AIDS in China, citing Chinese Public Security sources, estimated that there were four to six million sex workers in 2000.[5] In 2010 the official China Daily cited estimates ranging from three to ten million.[6] Others have used figures in police reports on anti-prostitution campaigns to estimate city-level rates, calculating that in 2000 Beijing had between 200,000 and 300,000 sex workers.[7] While many of these sources do not distinguish between numbers of women and men, or adults and children engaged in sex work or in situations of commercial sexual exploitation, adult women appear to constitute the overwhelming majority of sex workers.

Venues for Sex Work

Sex work occurs in many different venues in China.[8] While reported rates per service varied 30-fold in our research, there were some correlations between the rate and the type of venue, as noted below.

Sex work takes place in massage parlors, hair salons, and bathhouses and saunas. These venues sometimes signal the availability of prostitution with actual red lights visible from the street. Eight of the women we interviewed work in such places. Some of these venues offer the advertised services, such as massages and haircuts, as well as prostitution, but the client must specifically ask for “special services” (teshu fuwu.) Other such venues only offer sexual services. Participants in our focus groups said 120 yuan (US$18) was an average price per sexual service for such venues.

Women also solicit clients in public places such as streets and parks. In such cases, the sex act might take place in a secluded place outdoors but, more often, those involved go to the sex worker’s or client’s home, or rent a hotel room.[9] Participants in our focus groups said that 100 yuan (US$15) per sexual service was the norm for workers in streets and parks[10] Others noted that such workers can earn as little as 5 yuan (75 cents) per sexual service,[11] and one 63-year-old Beijing interviewee who solicits in parks told us she earned 30 yuan (US$4.5) per service.[12]

Entertainment establishments such as karaoke venues and nightclubs also serve as venues for sex work. Hostesses who work in such locations are expected to entertain clients, and talk, drink, and dance with them. For this reason, they are called “three accompaniments ladies” (sanpei xiaojie). Some of these women also sell sex to clients. Human Rights Watch interviewed two karaoke venue sex workers. They reported earnings of 100 to 500 yuan (US$15 to 75) per sexual service. Sex rarely occurs in the actual entertainment venue. Instead, they usually go to the client’s home, the sex worker’s home, or a hotel.[13]

Other venues for sex work include hotels[14] or private locations arranged through the Internet.[15]

Venues in which sex work takes place are typically run by managers (laoban), who are responsible for the overall business, such as food, drink, and music in karaoke bars. Madams (mami) work in these venues, and are responsible for all aspects of business that pertains to sex workers. They arrange transactions with clients, and usually receive a 10 to 30 percent commission.[16] Women who sell sex in public spaces often also work for madams or pimps. Some women work independently.

Factors Leading to Sex Work

Domestic surveys show that a majority of Chinese women engaged in sex work are migrants from rural areas or small cities who have not completed high school.[17]

Women engaged in sex work told Human Rights Watch that a number of factors contributed to their decision to enter into sex work. Their accounts echo findings by other researchers on sex work by women in China. The factors include poverty, lack of economic and educational opportunities for women (especially in the countryside), job loss, and divorce or separation.[18]

While not all sex workers face the constrained choices presented by these circumstances, none of the women interviewed by Human Rights Watch had other employment options that would provide earnings close to the earnings they anticipated in sex work. Lili, a widow who left her job selling clothes in her hometown in Henan to enter prostitution in Beijing, cited her ability to support her family as the main reason for selling sex services:

I earn a few thousand yuan a month, which is enough to support my family. It is much more than I could earn working in an office or doing manual labor.[19]

Xiao Li, who left her 13-year-old daughter with her parents in rural Hubei to work in Beijing, explained that her income was considerably higher as a sex worker than what she previously earned farming:

My income now [as a sex worker] is a couple thousand yuan a month, which is about four times more than I used to earn.[20]

Several interviewees said they entered the sex trade after losing financial support from their husbands. Both Mimi and Amei started selling sex after getting divorced.[21]

|

Gender Inequality and Prostitution in China Gender inequality is recognized the world over as an important reason that women engage in sex work and have little protection against abuse. In 2000, 11.3 percent of China’s rural population lived on less than US$1 per day, and Chinese researchers and scholars have underscored the feminization of poverty in China. [22] In addition, significant gender disparities exist in education. In the poorest regions, women are twice as likely as men to be functionally illiterate. [23] In 2000, 6.42 million women over the age of six had never been to school—2.5 times more than men. Only one-third of college-educated individuals in China are female. [24] Furthermore, unemployment disproportionately affects women, who are also less likely to be re-hired. [25] In the late 1990s, over 12 million workers at state-owned enterprises were laid off ( xiagang ). Many sex workers over the age of 40 are part of the generation of xiagang workers who turned to prostitution after losing their jobs. This was the case for Lingling, an older sex worker from the northeastern city of Harbin whom Human Rights Watch interviewed. [26] Non-prostitution job opportunities for women living in poverty include employment in factories, restaurants, retail, and domestic service. The average monthly salary of a migrant woman in the southern province of Guangdong who is not selling sex is 300 to 500 yuan (US$45 to 75). [27] As a sex worker, she might earn 4000 yuan (US$600). [28] |

Sex Work Under Current Chinese Law

Under Chinese law, all aspects of sex work—including solicitation, sale, and purchase of sex—are illegal. Most sex work-related offences are deemed administrative rather than criminal offenses under domestic law, and most are punished through the imposition of fines and short periods of police custody or administrative detention. The law nonetheless allows for long administrative detention sentences of up to two years for repeat offenders. Meager due process protections exist on paper but are largely absent in practice in China’s administrative detention systems, leading to frequent arbitrary detention.

Administrative penalties are set out by the Security Administrative Punishment Law, the 1991 decision on the Strict Prohibition Against Prostitution and Whoring, and a host of complementary regulations. Criminal penalties can apply to sex work-related offenses, but usually apply to third-party involvement, such as organizing the prostitution of others. Trafficking in persons is a criminal offense. These laws and regulations apply across China.

By law detaining a person for prostitution-related offenses requires evidence that sexual services were provided in exchange for money or property.[29] In practice, however, police frequently detain sex workers with little or no evidence, and have extensive powers to take suspects into custody for periods ranging from several days to several months.

While those suspected of engaging in sex work are not entitled to a state-appointed lawyer under Chinese administrative law. In theory they may also contact a lawyer if they believe their rights have been violated through, for example, a forced confession, or physical or sexual assault. None of the arbitrarily detained sex workers that Human Rights Watch interviewed had been offered the opportunity to seek legal counsel. Limited legal awareness also plays a role. A Chinese lawyer with experience on issues pertaining to sex workers’ rights told Human Rights Watch:

They are very surprised when they hear about their legal rights. They don’t have any legal knowledge. They don’t know that lawyers can protect them.[30]

Sex workers face one of four levels of administrative punishment that can be imposed entirely at the discretion of the police without court proceedings:[31]

- Five days of administrative detention, or a fine of up to 500 yuan (US$75) if the circumstances are judged “minor.”[32]

- Ten to 15 days of administrative detention, and/or a fine of up to 5,000 yuan (US$750) in “ordinary” cases.[33]

- An “educational coercive administrative measure” of six months to two years of detention in a Custody and Education (shourong jiaoyu) facility.[34]

- A sentence to Re-education Through Labor (RTL) (laodong jiaoyang) for up to two years (limited to repeat offenders).[35]

Fines

Only a small proportion of women suspected of involvement in sex work are actually incarcerated for prostitution.[36] Most are first detained, either on site or at the police station (paichusuo), often on grounds of “solicitation,” fined, and then released. According to the Ministry of Public Security, the fines help supplement the operational costs of local law enforcement.[37]

These fines are generally not recorded as part of the prostitution case data published in official annual statistical yearbooks, making it impossible to know how many such fines are imposed each year. The Ministry of Public Security warns local police against substituting fines for detention.[38] However, the practice is widespread.[39]

Fines for prostitution are an important source of extra-budgetary revenue for local law enforcement.[40] Local police at times have fixed quotas for the amount of money they are expected to collect through fines, even though the Ministry of Public Security prohibits such targets.[41] Discretion over the imposition of fines on sex workers also provides opportunities for corruption, as described by many sex workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch and detailed below.

Administrative Detention

Due process protections are virtually absent from the administrative detention systems in which prostitution offenders are held.[42] As noted above, defendants are not entitled to a lawyer, and a sentence to administrative detention is not decided by a court but by a committee headed by the police. There are no meaningful procedures to appeal or seek remedies for procedural violations.

As a result, both the Custody and Education system, which is administered by the Ministry of Public Security, and Re-education Through Labor (RTL), which is administered by the Ministry of Justice, constitute forms of arbitrary detention under international law since they allow individuals to be deprived of their liberty without due process of law.[43] Past research conducted on these institutions has documented widespread abuses, including arbitrary detention, forced labor, and physical and psychological abuse.[44]

The government does not disclose information on the number of individuals held in Custody and Education centers, and the exact number of centers is unclear.[45] In 2000, 183 such facilities existed, holding 18,000 inmates.[46]

The Custody and Education system is supposed to provide sex workers and clients with educational support, including literacy and vocational training; health monitoring, with testing and treatment for sexually-transmitted diseases (STDs); and work experience.[47] Previous research shows that, in practice, this system of incarceration largely fails to achieve its purported rehabilitative mandate, with forced labor by inmates taking precedence over the other stated goals.[48]

RTL is only imposed on sex workers who are repeat offenders. Since 1999 sex workers are increasingly sent to Custody and Educationinstitutions instead of RTL.[49] In January 2013 Chinese media reported that the government intended to “stop using” the RTL system by the end of the year.[50] However, there has been no such announcement for Custody and Education or forced drug detoxification centers, and the government may be considering setting up another system of administrative detention in place of RTL, rather than abolishing the system outright.[51]

In the Chinese legal system, individuals suspected of administrative offences enjoy far fewer procedural protections than do suspects in the criminal system. On paper, those charged with crimes are entitled to access to a lawyer within 48 hours of detention, among other defense rights, and are tried and sentenced by a court composed of a three-judge bench rather than police. In practice, however, the procedural rights of criminal suspects are also routinely violated and ignored by the judicial system.[52]

“Anti-Prostitution” Mobilization Campaigns

Enforcement of anti-prostitution statutes is at its most stringent during periodic public campaigns against crime in general, or prostitution and pornography in particular. During these campaigns, sex workers are most at risk of abuses such as police brutality and arbitrary detention.[53] These campaigns are often held simultaneously, with the “sweep away” component one aspect of a larger “strike hard” campaign.

“Sweep Away” Campaigns

A defining feature of China’s approach to prostitution are periodic “sweep away” (saohuang dafei) anti-prostitution campaigns. Thesecampaigns typically last between several weeks and a few months. During such periods, police repeatedly raid entertainment venues, hair salons, massage parlors, and other spaces where sex work occurs, force venues to close, and detain large numbers of women suspected of being sex workers.[54]

One such campaign, conducted in Beijing from April 20 to May 30, 2012, resulted in the closing of 48 entertainment venues, according to the Beijing Municipal Public Security Bureau.[55] In a second campaign, launched on June 26, the Beijing police raided 180 entertainment venues and detained 660 suspects in a two–week period.[56]

“Strike Hard” Campaigns

In addition to “sweep away” drives, Chinese law enforcement agencies periodically carry out massive drives against crime, called “strike hard” (yanda) campaigns. At various times, sex workers have been among the targets of these campaigns, including in 1983, 1986, 1987, 1989, 1991-1993, 1996, 2000, and 2009-2010.[57] Sex workers are particularly vulnerable to detention and abuse during such concentrated campaigns.

Sex worker organizations have reported a general increase in the focus on the “anti-prostitution” component of the strike hard campaigns in recent years, culminating in an exceptionally intense crackdown in cities throughout China in 2010.[58] The 2010 crackdown started in Beijing in April, with public raids on four elite karaoke venues, and gradually spread throughout the country.[59] Sex workers in cities throughout China reported increased detention and fines.[60] The 2010 crackdown was accompanied by the physical destruction of many venues in which prostitution was thought to take place.[61] Sex workers said they were beaten, blackmailed, and harassed during the 2010 crackdown.[62] Some said that, during the crackdowns, they stopped carrying or using condoms for fear that the police would use their possession of condoms as evidence of prostitution.[63]

Shame Parades

Police sometimes parade suspected sex workers through city streets in “shame parades” designed to “educate” the public. Although the practice has now been banned by the government, several shame parades were given media coverage during the 2010 campaign.[64]

Such public shaming events resulted in significant public outcry. Through internet posts and blogs, citizens expressed support for the women and criticized the police.[65] Following these reactions, the Ministry of Public Security issued a notice in July 2010 that called for an end to shame parades in anti-prostitution crackdowns.[66] Similar notices had been issued several times previously.[67] No sex worker shame parades have been reported in state media since July 2010, although the public shaming of individuals suspected of other offenses has occurred. Absent efforts to prosecute those who oversee public shaming efforts, it is possible they will occur again in the future.

Grassroots Organizations Supporting Sex Workers

There are currently about a dozen grassroots organizations in China that focus on issues pertaining to sex workers. Some of them are mainly service providers concentrating on health issues such as HIV/AIDS prevention. Others carry out rights awareness programs within sex worker communities and promote activities in support of the legalization of prostitution. Some of these groups have organized to create a forum whose mission is to “support the development of its members, [and] to improve the occupational health environment of sex workers so that sex workers can live and work in an environment free from discrimination with equal right to development.”[68] Among other activities, this forum collaborated to produce a report on the effects of the 2010 crackdown on the provision of health services to people who engage in sex work.[69]

Individual activists have also played a critical role in raising awareness about discrimination and violence against sex workers. Writer and activist Ye Haiyan, who blogs under the name “Hooligan Sparrow,” first began to raise such concerns in 2005, and has since documented police abuse of sex workers and the detrimental public health effects of possession of condoms being used as evidence of prostitution.[70]

In December 2012 a coalition of Chinese sex worker organizations took the unprecedented step of publicly circulating a petition calling for an end to violence against sex workers. The letter decried the lack of protection of personal safety for female, male, and transgender sex workers, citing 218 documented incidents, including eight in which sex workers were killed. The letter also mentioned that sex workers are often reluctant to use the law to protect their rights because they are often detained for illegal actions.[71]

These groups face challenging working conditions.[72] While Chinese civil society organizations generally encounter significant state-level resistance and harassment, sex worker organizations are in a particularly tenuous situation because they work with a population the government primarily sees through a law enforcement perspective. The China Grassroots Women’s Rights Center in Wuhan, founded by Ye Haiyan, has been the target of police raids in response to Ye’s activism.[73] One prominent grassroots organization had to shut down in 2011 after harassment by local officials left staff feeling it was unsafe for them to carry out their work.[74]

Peer educators for some sex worker NGOs report that the 2010 crackdown had a negative effect on their work. They found that “[p]revious prevention patterns are gone, and it’s more difficult for sex work peer educators to find target groups, which will decrease the health services provided.”[75]

II. Police Abuse of Sex Workers

I was beaten until I turned black and blue, because I wouldn’t admit to prostitution.

—Xiao Yue, interviewed in Beijing, 2011

In 2000, law enforcement agencies launched a campaign to strengthen control and management of recreational and entertainment facilities, and combat the vice of prostitution, during which 38,000 cases of prostitution, involving 73,000 individuals, were investigated and dealt with.

—Official Chinese report to the UN Committee for the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, 2004[76]

Sex workers report a wide range of abuses at the hands of the police. These range from arbitrary arrests and detention to physical violence, ill-treatment, violation of due process rights, use of condoms as evidence of prostitution, and discrimination by law enforcement officials when sex workers try to report crimes or abuse.

In researching this report, we focused on police abuse of women engaging in sex work in Beijing. Although many of the women we interviewed could not specify which police units were involved, the law enforcement officers most often involved in enforcing criminal and administrative laws on prostitution in Beijing are from the local Public Security Bureau (PSB). PSB regulations explicitly prohibit police from beating, insulting, using disproportionate force, fining arbitrarily, or confiscating property from suspects and members of the public.[77]

Beatings, Ill-Treatment, and Torture in Custody

Police violence against sex workers is often most serious at the initial detention stage, when the police seek to have suspects confess to engaging in prostitution. Confessions relieve police officers from the more onerous task of finding and presenting conclusive evidence of prostitution. The coerced confessions serve as the basis for deciding the administrative punishment that will be imposed by the police or, in some cases, by the police-run Re-Education Through Labor committee. This problem is not unique to cases involving sex work.[78]

Several women interviewed by HRW said that when police arrested them, they beat them to coerce confessions. Experts on sex work and police practices in China say this is a common occurrence.[79]

Xiao Yue, a laid-off worker from the northeastern province of Heilongjiang, told us she was assaulted in police custody in Beijing in 2009 for refusing to admit she was engaging in sex work:

I was beaten until I turned black and blue, because I wouldn’t admit to prostitution. They kept yelling at me, “Fuck you! Just admit it!”[80]

Some of the abuses meted out to sex workers in police custody constitute torture under domestic law. According to Mimi, who said she was assaulted by police along with two colleagues Yuanyuan and Shishi:

They attached us to trees, threw freezing cold water on us, and then proceeded to beat us.[81]

Xiaohuang says she was beaten by police in Beijing:

The first time I was arrested, they had no proof of prostitution. The police interrogated me, and threatened me. They used verbal abuse and violent methods to make me confess. I refused to, regardless of how hard they beat me. They finally let me go.[82]

Yingying, a 42-year-old from Chongqing, recounted:

The police will sometimes extort confessions out of you. They’ll beat and insult sex workers, and extort confessions out of you. If you can’t endure the process, then you just give up and admit [it].[83]

Xiao Li, from rural Hubei, told Human Rights Watch that admitting to sex work under duress also entails risks:

After you are arrested and taken to the police station, they need to get you to admit [to prostitution]. They look for evidence. If you don’t admit, they’ll beat you. But if you can bear the beating, usually they’ll detain you for 24 hours and then let you go. But if you admit to prostitution when they beat you, [you might] be sent to Re-education Through Labor for six months.[84]

Experiences of manifestly unlawful abuses while in police custody, as well as the trauma that often results from such episodes, constitute a powerful deterrent for sex workers to turn to other police to report these or other crimes. None of the women we interviewed said they had lodged a complaint or filed criminal charges against police who had abused them.

Violence at the Time of Arrest

Although the worst abuses documented by Human Rights Watch took place while women were in custody, several interviewees also said they experienced police brutality while being arrested. Mimi, who has been soliciting sex in a park in Beijing since she divorced her husband in 2000, told Human Rights Watch that a police officer hit her head against the wall while he was arresting her: “The police ran after me, grabbed me, and smashed my head into the wall.”[85]

Neighborhood level police sometimes employ “auxiliaries” (zhi’an lianfang), who are not generally trained or monitored, and who have a reputation for brutality among sex workers.[86] Auxiliaries are contractors who are not officially part of the police force but assist police officers in their missions.[87] Several women interviewed by Human Rights Watch said auxiliaries beat them during arrests for suspected prostitution. Xiao Mei told of having been beaten by police auxiliaries in Beijing in 2010 under the watch of police officers:

Last year when I was soliciting on the street, the police just came and started beating me. They made the assistant police beat me. There were five or six of them; they just beat me to a pulp.[88]

Meimei, a young woman from Hebei who solicits in a public park in Beijing, also told Human Rights Watch that she had been beaten by an auxiliary acting on the orders of a police officer:

Once in 2005, I had already settled on a price with a client. But I had a feeling that someone was following us from behind, so to be safe, I told the client that I wasn’t willing to do it. I got arrested anyway. The police officer said the client had solicited me, and wanted me to admit it. Because I didn’t admit it, the assistant police beat me, and as he was beating me he said there was a reason he was beating me, I was a whore. The police officer stood by the side and watched. He pretended that he didn’t know what was going on. That is the most horrible thing that has ever happened to me in my life.[89]

Arbitrary Arrest and Detention

Women engaged in sex work interviewed by Human Rights Watch described severe procedural irregularities in the arrest process. Interviewees reported that police rarely told sex workers why they were being detained or whether they were charged with an offense.

Caihong, for example, said:

I was once arrested when I was just in the venue. I wasn’t doing anything. When I was arrested, I don’t know what reason they gave to detain me. They didn’t say.[90]

Zhanghua, who had just arrived in Beijing a month prior to her arrest and was working in a hair salon but had not yet become involved in the sex trade, told Human Rights Watch that she was falsely accused of selling sex and that the police forced her to confess:

They told me it was fine, all I needed to do was sign my name and they would release me after four or five days. They deceived me into signing. That is really morally reprehensible. Instead, I was locked up in Custody and Education center for six months.[91]

In some cases, sex workers are released after detention at the police station, oftentimes after paying a fine or a bribe:

I was once arrested and had to pay a 3,000 yuan (US$485) bribe to be let go. I know it was a bribe because the police didn’t give me a voucher receipt. I know they should give one because I attended a NGO training. That’s how I learned that they were not following the right procedures. [92]

She said the police did not return the money to her once she was released.

Sex workers also run the risk of being arrested and detained as retribution against managers of entertainment venues who have displeased local power holders. Tingting, a 31-year-old karaoke hostess in Beijing, described one such incident:

When I was working at [a previous entertainment venue], they [the police] told us we were arrested because our boss offended someone. That was the first time I was arrested. They just kept us for a couple hours and released us.[93]

Zhanghua, who worked in a massage parlor that also provides sexual services, said the police were predisposed to trust false statements from clients:

One client came to our massage parlor to get a regular foot massage. He left after a few minutes, because he thought the price of the foot massage was not appropriate. A few minutes later, the police came and arrested us for prostitution. They said the man had said we offered him sexual services. But we had not. I felt so wronged. Those police officers will do whatever it takes to get the results they want.[94]

One woman told Human Rights Watch that it was illegal for police to arrest clients:

The police don’t have the right to interrogate clients, they are only allowed to interrogate sex workers. If they are good clients, they’ll say the girl is a friend of theirs and that there isn’t a problem. If it’s a bad client, then the girl will get into trouble.[95]

In fact, by law, clients as well as sex workers are liable for legal penalties and, particularly during anti-prostitution drives, some clients are fined or administratively detained.

Other Violations

Use of Condoms as Evidence of Prostitution

As mentioned above, administrative punishments for prostitution in China, including fines and fixed-term detention, require evidence that sexual services were provided in exchange for money or property.[96] Despite regulations specifically forbidding the practice, sex workers told Human Rights Watch that on occasion police in Beijing used mere possession of condoms as evidence of prostitution.[97] This practice deters sex workers from carrying condoms, putting them at increased risk of HIV.[98] One woman told Human Rights Watch:

In the police station…they will look to see if you have condoms, and will ask you why. The law says it is not a problem [to carry condoms], but the police act differently.[99]

Several women engaged in sex work reported that police interrogated them about why they had condoms without any evidence of prostitution. Shushu, for example, said that when police in Beijing questioned her they asked her about condoms she had in her possession:

They saw my condoms, and asked how many I use every day, how many men do I have sex with.[100]

In addition, police reports of sex worker detentions, as recounted in Chinese media, frequently note the number of condoms found at the scene.[101] For example, a Hainan news outlet in 2009 reported on the police gathering condoms to use as evidence at the scene of a prostitution arrest.[102] Similar cases have been reported elsewhere.[103]

Entrapment, Bribes, and Police Solicitations for Sex

Law enforcement agents sometimes extort sex from sex workers. Several interviewees reported having police officers as clients who do not pay for sexual services, allegedly in exchange for protection for the venue. Jia Yue, who works in a massage parlor in Beijing, said:

One local police officer here said that if we had sex with him, he would protect us. Police won’t pay in those cases. If they want sex, they’ll get sex from us. But when we asked for his help once, he didn’t help. The police really don’t care about sex workers.[104]

Jingying, a 23-year-old from Sichuan who works in Beijing, said police had also extorted sex from her, and she felt it was futile to report this to the police:

At first, I didn’t know he was a police officer. After three hours, he refused to pay. The boss told me to let it go because he was a cop. I felt really wronged, but didn’t get any money. You can’t report that kind of thing to the police. Lots of them come here.[105]

Xiao Yue, who started selling sex in Beijing after being laid off from her factory job in Heilongjiang, reported a police officer posing as a client, having sex with her, and then arresting her. After arresting her, the undercover police officer allegedly said to her:

We can solicit sex wherever we want, whenever we want. After we’re done, we still have our job to do, we will still crack down on prostitution.[106]

Jianmei, a 22-year-old from Sichuan working in a massage parlor in Beijing, told Human Rights Watch that police entrapped her and other sex workers in order to extort money:

The police are really unfair. In this neighborhood, when there are crackdowns and they want to earn more money, they arrange to have a client come into our venue and ask for sexual services. Once the services have started, the client calls the police, who arrest us both. They then fine the sex worker, and split the money with the client.[107]

Sex workers are sometimes victims of police retribution if they refuse their sexual advances:

One off-duty police officer solicited me one night. He was really drunk, and very rude. I had to hit him with my purse and run away from him. He and some other police officers arrested me the next day and detained me overnight…It’s because I hit him.[108]

Women in sex work also said that at times police officers extort bribes from clients in facilities they raid:

Police once busted us—three men and two girls. They came in with a gun. The guys just handed over 30 or 40,000 yuan (US$4,500-6,000) and they left. The police then took us in to the station.[109]

Xiao Mei, who had been arrested five times in 2008-2009 by the police in Beijing, described how police used their knowledge of her past arrests to extort money from her:

Last time I was arrested, I was just standing on the street doing nothing wrong. The police took me in, and put a lot of pressure on me. They forced me to admit that I had engaged in prostitution. I paid a 3,000 yuan fine (US$485) and they let me go after 24 hours.[110]

Barriers to Justice after Client or Police Abuse

Women engaging in sex work face significant barriers to justice after abuse by police, clients, or managers. All women engaged in sex work interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that they felt it was futile to report crimes committed against them to law enforcement officers. They said they believed the police would refuse to investigate complaints if police suspected the women were engaged in prostitution, would not undertake serious investigations of fellow police officers, or might even detain the women themselves if they exposed that they were victims in the course of engaging in sex work. The few sex workers who had reported crimes said the police did not pursue the cases. Domestic Chinese NGOs have reported similar findings.[111]

Xiaohuang, from rural northwestern China, told Human Rights Watch that Beijing police refused to accept her complaint when she tried to report that someone had drugged her by spiking her drink in a bar:

I was working in an entertainment venue, and left to go to the bathroom. I think the client spiked my drink then […] I passed out. I don’t remember what happened afterwards, I only woke up the next day feeling horrible. I went to the police but when I told them where I worked, they told me to leave and that I deserved it.[112]

Juanxiu, a 42-year-old from Zhejiang province who worked in a foot massage parlor in Beijing, reported similar lack of police response when she was robbed:

Once three men came into our venue. They noticed my purse hanging by the door. When they left, they just took it away with them. I reported it to the police. But they weren’t going to make a concerted effort to find it…The police won’t take us seriously.[113]

Xiaoyue, who has been selling sex for 17 years to pay for her son’s education, told Human Rights Watch that she had been raped by a client, but that when she reported it to the police, she felt like they did not take her claim seriously:

It had no effect, and I felt like I could not voice my grievance.[114]

One woman said she was convinced that filing a criminal complaint after she was robbed led to many subsequent detentions for prostitution. Xiaojing said:

I was once robbed at knifepoint by a client…I decided to follow the rules like a normal person [i.e., a non-sex worker], and reported the crime to the police. But the case was never solved, there was no outcome… After that, I was arrested for prostitution many times by the police, they identified me as a sex worker because I had reported the robbery.[115]

Another said:

I’ve encountered clients who have stolen my cell phone, or who haven’t paid me. I’ve dealt with it on my own, or have asked friends to help. I don’t seek out the police. Other sex workers I know who have encountered such problems also just deal with it on their own.[116]

Mimi, a farmer in Henan prior to moving to Beijing and entering the sex trade, told Human Rights Watch:

My friend got her bag stolen by a client, who also beat and wounded her. She eventually reported it to the police, but they refused to handle the case.[117]

Mimi said that her friend’s experience made it unlikely she would report anything the next time she was a victim of crime. Some sex workers do not contact police even when they are victims of serious physical and sexual violence, including rape:

I’ve been raped several times. But because I am a sex worker, and selling sex is a violation of the law, I could be arrested. So I have never been willing to report to the police. I just have to grin and bear it.[118]

Lingxue, who recounted having been raped, said that she had not contacted the police:

I went to a hotel with one client, and when I arrived, three of his friends were also there. They raped me all night. I wasn’t willing to report to the police. I just cried for weeks. My friends told me to report it.[119]

Similarly, Lili said:

If I experience client violence, I’ll try to talk him out of it. If it is really unbearable, I’ll just leave without getting paid. In any case, I would never report to the police.[120]

Some women engaged in sex work told Human Rights Watch that they had not reported crimes committed against fellow sex workers, also out of fear or a sense of futility. Manqing said she once saw a woman who was taken away unconscious by the client who had beaten her at their workplace in Beijing:

Once a client started kicking and beating a girl who worked in our venue. He beat her unconscious. Then, he took her away in his car. We didn’t call the police because we didn’t want to encounter any trouble. I don’t know what happened to her that night, but she eventually came back to work.[121]

Even women who had previously been victims of trafficking told Human Rights Watch that, at the time, they did not dare seek police assistance. Mengfei, trafficked into forced prostitution at age 15, said that even though the police came to the venue where she was working, she was too afraid to approach them:

I met a woman who said she would help me find a job and feed me. When she told me she would pay me 2,000 yuan (US$324) to host clients in a karaoke bar, I wanted to run away. But I couldn’t escape. Then, she and her boyfriend told me that I would have to sell sex. I hid in a room and cried, and when they found me, they beat me and broke my nose. Then they forced me to work…The police once came to the karaoke bar, but I was too scared to ask for help.[122]

The failure of law enforcement to respond appropriately when crimes against sex workers are brought to their attention leads to severe under-reporting of such crimes. It also contributes to the perception that crimes against sex workers are less serious and less worthy of investigation than crimes against people who do not engage in prostitution.

Police Abuse as a Violation of Domestic Laws, Regulations, and Policies

Many of the abuses described above are clear-cut violations of existing Chinese law.

Arbitrary sentencing to detention violates the Regulations on the Procedures for Handling Administrative Cases by Public Security organs. These regulations require that at least two officers investigate an unlawful act, and that they show official identification.[123] The suspect is to be summoned to the police station and interviewed.[124] A permanent written record of the interview must be made and approved by the suspect.[125] A written decision must provide evidence, and reasons and legal basis for the decision.[126] The suspect must be informed of their right to appeal the decision, and must be able to appeal without fear of being penalized even more harshly.[127]

Physical abuse and torture of sex workers by police, and police sex with a sex worker prior to arrest, are violations of the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China, the People’s Police Law of the People’s Republic of China, and the Prison Law of the People’s Republic of China.

Article 38 of the Constitution guarantees “the personal dignity of citizens.” According to the Police Law, law enforcement agents must “exercise their functions and powers respectively in accordance with the provisions of relevant laws and administrative rules and regulations.”[128] They may not inflict bodily punishment on detainees.[129] The Prison Law prohibits guards from violating the personal safety of detainees, using torture or corporal punishment, beating or conniving with others to beat a prisoner, or humiliating the human dignity of a prisoner.[130]

The use of condoms as evidence of prostitution is a violation of the 1998 “Notice on Principles for Propaganda and Education Concerning AIDS Prevention,” which instructs police to “refrain from using condoms as evidence of prostitution.”[131]

The National Human Rights Action Plan of the Chinese government denounces “corporal punishment, abuses, insult of detainees or extraction of confessions by torture.”[132] It further requires police and prison authorities to “undertake effective measures to prohibit abuse and insult of detainees.”[133]

In failing to take crimes against sex workers seriously, the police are violating the Police Law, which obligates them to “prevent, stop and investigate illegal and criminal activities.”[134] Police who fail to do so are guilty of dereliction of duty and liable to administrative sanctions and possible criminal prosecution.[135]

Chinese activists have argued that public shaming is also a violation of the Chinese Constitution, which guarantees that “[t]he personal dignity of citizens of the People’s Republic of China is inviolable. Insult, libel, false accusation, or false incrimination directed against citizens by any means is prohibited.”[136]

Police Abuse as a Violation of International Law

Arbitrary arrest and detention of sex workers is a violation of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). Although China has not ratified the ICCPR, it is a signatory, and should thus abstain from taking steps that contravene that Covenant.[137] The ICCPR stipulates that “[e]veryone has the right to liberty and security of person. No one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest or detention. No one shall be deprived of his liberty except on such grounds and in accordance with such procedure as are established by law.”[138] At the time of their arrest, everyone “shall be informed…of the reasons for his arrest and shall be promptly informed of any charges against him.”[139] Any person detained on grounds that are not in accordance with the law is detained arbitrarily and therefore unlawfully.

Detention is also considered arbitrary, even if authorized by law, if it includes “elements of inappropriateness, injustice, lack of predictability and due process of law.”[140]

Physical beatings and public shaming of sex workers constitute torture or cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment under international law, as well as violations of the right to physical integrity guaranteed under article 9 of the ICCPR. China is a party to the U.N. Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment.[141]Article 1 defines torture as “any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as…intimidating or coercing him …when such pain or suffering is inflicted by…or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity.”[142]

Under its obligation as a party to the U.N. Covenant on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), China has agreed to pursue by all appropriate means and without delay a policy of eliminating discrimination against women.”[143] The U.N. Committee on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women, a committee of experts that monitor states parties implementation of CEDAW, has clarified that the anti-discrimination provisions of CEDAW apply to gender-based violence, defined as “violence that is directed against a woman because she is a woman or that affects women disproportionately. It includes acts that inflict physical, mental or sexual harm or suffering, threats of such acts, coercion and other deprivations of liberty.” Police violence disproportionately directed at women suspected of engaging in sex work constitutes a form of gender-based discrimination.

Article 6 of CEDAW requires that states take measures to suppress all forms of trafficking in women and exploitation of the prostitution of women. The CEDAW Committee has emphasized that: “Poverty and unemployment force many women, including young girls, into prostitution. Prostitutes are especially vulnerable to violence because their status, which may be unlawful, tends to marginalize them. They need the equal protection of laws against rape and other forms of violence.”[144]

III. Abusive Public Health Practices Against Sex Workers

[The ministries] are committed to protecting these women's rights to health, their reputation and privacy.

—China Daily editorial, December 15, 2010

The CDC tested me last year. But they never told me the results. I hope I don’t have AIDS.

—Zhangping, a sex worker interviewed in Beijing

Sex workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that they faced mistreatment by public health workers in Beijing. They described practices that violate their rights to health and privacy, including forced HIV/AIDS testing, which remains legal under Chinese law; violations of privacy and patient confidentiality; disclosure of HIV/AIDS test results to third parties; disclosure of test results to patients without provision of appropriate health services; lack of access to personal medical records; and mistreatment by health officials in charge of testing and providing health services to sex workers. These violations occur in implementation of government policies designed to curb the spread of HIV/AIDS policies that specifically identify sex workers as a “high risk” group.

In some instances, these abuses drive sex workers away from public health agencies, especially when the latter work closely with law enforcement agencies. The situation is compounded by government restrictions on sex worker NGOs, making it less likely that HIV/AIDS education and other programming will reach the least accessible segments of the sex worker population.

These practices directly undermine China’s public health objectives of reducing the burden of HIV/AIDS within communities of sex workers, and successfully reducing HIV/AIDS in the population at large.

For HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted infections to be successfully reduced in China, marginalized populations such as sex workers must be able to obtain HIV information, prevention, and health care without fear of mistreatment or discrimination.

This section describes the experiences of women engaged in sex work who have come into contact with public health authorities in Beijing, especially the local offices of the Chinese Center for Disease Control (CDC). Beijing health authorities apply national health policies, and the findings are thus likely to be relevant beyond Beijing.

Forced and Coercive Testing of Sex Workers, Violations of Privacy Rights

Reflecting increased public concern about privacy, the Ministry of Health has issued policy statements calling on the CDC to “strictly guard secrecy for [AIDS] sufferers,” and for healthcare workers not to release medical information to third parties. The State Council has issued a comment forbidding the publication or transmission of information, including names and addresses, of HIV/AIDS patients. Yet public health authorities such as the Ministry of Health and CDC are still allowed under Chinese law to carry out HIV testing without prior consent of the tested, and are not obliged to disclose the test results to those tested.

National law and local regulations permit mandatory HIV/AIDS testing of sex workers.[145] In Beijing, the main agencies that carry out testing for HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases are local offices of the CDC. Beijing regulations also allow the police to require that sex workers get tested, and do not require their consent.

Internationally, the “3Cs”—confidential, counseling, and consent— advocated since the HIV test became available in 1985, continue to be the basic principles guiding HIV testing for individuals. Such testing of individuals must be confidential, accompanied by counseling, and conducted only with informed consent, meaning that testing should be both informed and voluntary. Mandatory HIV testing violates fundamental rights to the security of the person, and the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, both protected by international treaties to which China is a party.

Several interviewees told Human Rights Watch of having been forcibly tested by CDC or detention center staff, either in detention centers or while working in venues monitored by the CDC.[146]

Shushu, for example, said she had been tested without consent after she was brought to a clinic by Beijing police:

When I was arrested, they brought me to the detention center, but first they took me to the health clinic next door to get an AIDS test and a pregnancy test. You have to do the tests.[147]

Lanying, a 25-year-old from Guizhou province, told of being tested by a person she believed was a public health official in the venue where she worked in Beijing:

Once when I was at the venue someone came to do testing. The boss [of the venue] told us to do it so we all did it. Most sex workers just do what the boss tells them to do. I don’t know what would have happened if we didn’t want to do the test…They said it was to test if we have AIDS…I don’t remember if they came back to tell us the results.[148]

The coercive and forced testing of sex workers has been documented in several studies by the Beijing Aizhixing Institute, a civil society group.[149] The institute has repeatedly raised concern about national and local regulations that permit forced testing of sex workers.

One Chinese CDC employee in Beijing and two foreign public health experts working for foreign governments who have direct experience in the matter told us of HIV testing practices that do not appear to involve informed consent.[150] According to the Chinese CDC employee:

The local CDC develops relationships with brothel managers to do blood tests. They cultivate relationships with the managers, who then tell their girls to participate.[151]

This practice can be problematic because sex workers are under the authority of their managers, and cannot easily opt out of testing. According to sex workers who participated in the focus groups that Human Rights Watch conducted, they fear retribution, such as beatings or losing their job, if they do not obey manager instructions.[152]

A staff member of a sex worker nongovernmental organization explained how some of the testing occurs: “Once the CDC has established a relationship with the manager, they go to the venue and test everyone.”[153]

The representatives of international organizations that collaborate with the Ministry of Health and the CDC expressed concern to Human Rights Watch about the voluntariness of HIV testing of sex workers. One staff member rejected the term “forced testing” but said that the practices were “coercive”:

It isn’t totally forced testing. But there is coercion.[154]

Many of the sex workers interviewed by Human Rights Watch were hesitant to get tested for HIV/AIDS because they feared the results would be disclosed without their consent. They fear repercussions if they test positive, such as social ostracism and unwanted state intervention in their lives.[155] One Chinese civil society activist told Human Rights Watch that CDC employees violated sex worker privacy and patient rights when conducting HIV testing. In some cases, test results are disclosed to third parties. Venue managers, for instance, are sometimes given access to test results. One CDC official explained:

When we collaborate with managers [who give health workers access to sex workers], they say that we have to give them the test results.[156]

One civil society representative described to Human Rights Watch having observed CDC officials in Beijing displaying test results publicly:

I accompanied several sex workers to get tested. We waited for the results, and when they came, they just put them out on a table for everyone to see. And two of them tested positive.[157]

The CDC does not systematically report test results to sex workers. If HIV/AIDS results are positive, they will contact them to draw blood again and get a second test. However, reporting of negative results occurs inconsistently, creating confusion amongst sex workers.[158] Zhangping, who engages in sex work in Beijing, told Human Rights Watch:

The CDC tested me last year. But they never told me the results. I hope I don’t have AIDS.[159]

Human Rights Watch also spoke with a CDC employee who said that they sometimes draw blood without telling sex workers that they are testing them for HIV/AIDS.[160] A public health academic familiar with CDC outreach also said CDC staff members sometimes tell women working in entertainment venues that they are drawing blood as part of a general physical exam, without providing details on the types of tests they will conduct.[161]

These practices are clearly at odds with the CDC’s own mission statements, which provides that it must provide HIV/AIDS counseling and treatment for sex workers, a process “in which individuals make an informed decision about undergoing an HIV test after receiving adequate counseling… with all aspects of the individual session and results being kept strictly confidential.”[162]

|

Eliminating Anonymous HIV Tests In February 2012 a domestic debate emerged at the occasion of a push for the elimination of anonymous HIV testing. The local congress in Guangxi province, which has one of the highest HIV rates in the country, proposed legislation requiring that individuals getting an HIV test provide their real name. [163] The proposal aims to facilitate contact between health officials and individuals who test positive for HIV. [164] The director of the China CDC, Wang Yu, has spoken out in support of the proposal. [165] Some Chinese civil society activists and researchers have spoken out against this proposal, suggesting that it would reduce the number of people willing to get tested. [166] |

Allegations of CDC Personnel Mistreatment of Sex Workers

Sex workers have also reported poor treatment by staff at some government run health clinics in Beijing where they can get an HIV/AIDS test.

One interviewee told Human Rights Watch:

I don’t go to those [government-run] clinics anymore. They were really disdainful of me when I went last time. Also, I was scared they would report me to the police. I was embarrassed to ask them any questions.[167]

Chinese NGOs working with sex workers are uniformly critical of the attitude of CDC staff in Beijing towards sex workers. According to one staff member:

Sex workers feel uncomfortable when they go to the clinic, because CDC staff will give them dirty looks. It is an attitude problem at the CDC.[168]

One member of an international NGO familiar with CDC sex worker outreach programs described the attitude of CDC personnel, which the individual had directly observed. In this individual’s view, the CDC’s treatment of sex workers is driving them away from needed services:

The CDC needs to provide sex-worker-friendly services. The clinics discriminate against sex workers, and are judgmental. I have heard that sex workers have gone to the clinic, whose staff knows they are sex workers, looks down on them, and treats them poorly. Because the clinics are not open and friendly, sex workers do not want to go there.[169]

Domestic activists charge that the mistreatment that sex workers experience in interactions with health workers amounts to a violation of “the personal dignity of citizens of the People’s Republic of China,” guaranteed under article 38 of the Chinese Constitution and the provisions contained in the 1992 Law on the Protection of Women’s Rights and Interests.[170]

Health Abuses and International Law

China is a party to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR).[171] Article 12 calls upon state parties to “recognize the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health,” and to create “conditions which would assure to all medical service and medical attention in the event of sickness.”[172] Article 2 stipulates that states must “take steps, individually and through international assistance and cooperation…with a view to achieving progressively the full realization of the rights recognized in the present Covenant.”[173] CEDAW also provides in article 12 that “States Parties shall take all appropriate measures to eliminate discrimination against women in the field of health care in order to ensure, on a basis of equality of men and women, access to health care services.”

General Comment 14 of the U.N. Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights provides a framework for understanding the right to health. It specifies that this is a right “to a system of health protection which provides equality of opportunity for people to enjoy the highest attainable level of health.”[174] It proscribes “any discrimination in access to health care and underlying determinants of health.”[175] The CEDAW Committee’s General Recommendation 24 on the right to health also calls on states to give special attention to the health needs and rights of “disadvantaged and vulnerable groups, such as… women in prostitution….” [176]

International law also prohibits non-consensual medical procedures. The ICESCR’s General Comment 14 declares that the right to health includes “the right to be free from interference, such as the right to be free from…non-consensual medical treatment.”[177] The CEDAW Committee’s General Recommendation 24 provides that states should “Require all health services to be consistent with the human rights of women, including the rights to autonomy, privacy, confidentiality, informed consent and choice.”[178]

The U.N. HIV/AIDS and Human Rights International Guidelines specify that “public health legislation should ensure that HIV testing of individuals should only be performed with the specific informed consent of that individual.”[179] These guidelines also explicitly reject all forms of mandatory and compulsory HIV testing, and make plain that HIV testing should be voluntary.[180]

The coerced testing and discrimination reported above violate these international laws and principles. Such behavior conflicts with the article 12 stipulation to create conditions that “assure to all medical service.”[181]

Mandatory HIV testing violates fundamental rights to the security of the person[182] and the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health[183] protected by international treaties to which China is a party.

IV. Recommendations

To the State Council:

- Publicly and unambiguously acknowledge and condemn abuses by police against sex workers.

- Publicly commit to strict nationwide enforcement of provisions that prohibit arbitrary arrests and detentions, police brutality, coerced confessions, and torture, and ensure swift prosecution of police officers who violate these provisions.

To the National People’s Congress:

- Enact legislation to remove criminal and administrative sanctions against voluntary, consensual adult sex work and related offenses, such as solicitation.

- Initiate consultations with sex workers and relevant nongovernmental organizations to consider other legislative reforms to better protect the rights of sex workers.

- Enact reforms to ensure enhanced oversight of the police and appropriate disciplining of offenders.

To the Ministry of Public Security:

- Ensure that crimes against sex workers are properly investigated, and actively encourage reporting of crimes against sex workers.

- End periodic mobilization campaigns to “sweep away prostitution and pornography” (saohuang dafei) that have generated widespread and severe abuses against women engaging in sex work.

- In collaboration with civil society organizations working on the rights of sex workers, carry out police awareness trainings to encourage appropriate treatment of sex workers.

- Initiate a public education campaign promoting the legal rights of sex workers, the illegality of police and public health abuse against them, and the due process rights of all suspects under Chinese law and international instruments.

- Law enforcement agencies should immediately cease official interference with, or police harassment of nongovernmental organizations promoting and protecting the rights of sex workers.

- Prohibit police from using the possession of condoms as grounds for arresting, questioning, or detaining persons suspected of sex work, or as evidence to support prosecution of prostitution and related offenses. Issue a directive to all officers emphasizing the public health importance of condoms for HIV prevention, and sexual and reproductive health. Ensure that officers are regularly trained on this protocol and held accountable for any transgressions.

To the Ministry of Health and the Center for Disease Control:

- Immediately end mandatory HIV/AIDS testing of sex workers, require informed consent prior to testing, inform anyone tested for HIV of the results, make appropriate counseling available before and after the test, and implement testing programs that conform with international standards.

- Publicly acknowledge and condemn abuses by public health officials against sex workers.

- When there are credible allegations implicating government employees in abuse of sex workers, suspend the employees pending investigation of the allegations.

- Provide training to Chinese Center for Disease Control HIV/AIDS treatment site staff on confidentiality, stigma and discrimination, and related subjects. Retrain or discharge staff who discriminate or behave inappropriately towards sex workers.

- Expand access to voluntary, affordable, community-based health care for sex workers.

- Give a greater role to civil society organizations in conducting HIV/AIDS testing, outreach, and education of sex workers, as such organizations frequently develop relationships of trust in local sex worker communities.