This year’s 75th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights takes place amid a backdrop of extreme economic inequality. Around 80 percent of the world’s population lives on less than $25 a day, a threshold deemed by the World Bank as the prosperity standard, leaving many people’s economic, social, and cultural rights out of reach. Meanwhile the top 10 percent amasses a staggering 76 percent of global wealth, as highlighted in the 2022 World Inequality Report.

However, extreme inequality isn’t inevitable. Human rights, anchored in universally recognized values and reinforced by legal obligations, provide a compass for policies that can advance economic justice. Aligning policies with human rights norms and standards can correct power imbalances and tackle poverty, laying the foundation for fairer and more inclusive societies.

In this context, an often neglected but transformative human right is the right to social security.

Article 22 of the Universal Declaration asserts that “Everyone, as a member of society, has the right to social security.” This was turned into a legally binding obligation in, among others, the International Covenant on Economic Social and Cultural Rights’ Article 9, and social security is mentioned in at least 119 constitutions around the world.

Yet, 75 years after governments committed to upholding the right to social security, it remains elusive for over half of the world's population, particularly in Africa. Without social security benefits, many children are forced to drop out of school and work to support their families; older people and people with disabilities who may face a heightened risk of income insecurity rely on friends and family to survive.

The Covid-19 pandemic briefly brought social security to the forefront as governments swiftly introduced and expanded income support systems, demonstrating that societies can alleviate inequality and avert social and economic catastrophes. Regrettably, these programs were dismantled just as quickly. With 143 countries and 85 percent of the world’s population estimated to face post-pandemic austerity, the specter of social security fading into obscurity looms large.

To reclaim the right to social security, let’s explore three fundamental questions, dispelling misconceptions that have hindered progress.

What does social security entail?

Part of the problem is limited awareness of what social security actually is. Perceptions vary considerably from one country to another, reflecting decisions about coverage, funding, and eligibility. In the United States, it is synonymous with an old-age social insurance program. In Nepal and Lebanon, it often refers to contributory social insurance programs for formal sector workers, with terms like “social safety net” or “social protection” encapsulating additional benefits for informal workers.

The human rights framework offers clear guidance on what it should include. The international expert committee tasked with interpreting the international covenant defines it to cover at least nine areas of support (see Graph 1).

Graph 1 – 9 Principal Branches of the Human Right to Social Security

Source: Human Rights Watch, based on CESCR 2007.

The International Labour Organization further specified in Recommendation No. 202 that national social protection floors should guarantee, as an initial minimum, to build on at least four aspects of social security:

- access to a nationally defined set of goods and services, constituting essential health care, including maternity care, meeting the criteria of availability, accessibility, acceptability and quality;

- basic income security for children, providing access to nutrition, education, care and any other necessary goods and services;

- basic income security for individuals of working age who are unable to earn sufficient income, particularly in cases of sickness, unemployment, maternity and disability; and

- basic income security for older persons.

Just as with any other human right, governments must uphold the right to social security without discrimination on the grounds of gender, age, disability, race, nationality or immigration, or other status.

Who should benefit?

According to the Universal Declaration, “all are equal before the law”. This principle extends to the right to social security, signifying that every individual is a potential beneficiary. This doesn’t imply that everyone should always receive social security, but rather the ability to get it when needed to uphold human rights and in the nine areas of support outlined in the international covenant.

Contrary to the intuitive idea that targeting social security at the poorest is the most effective use of resources to address poverty and inequality, research by the United Nations and independent groups suggests that societies embracing universal policies tend to have lower levels of inequality. More fundamentally, relying on targeting risks can create a dual structure—one aimed at people living in poverty and funded by the state, and another aimed at the better off and provided by the private sector. Or, as Nobel Prize recipient Amartya Sen, argues, “Benefits meant exclusively for the poor often end up being poor benefits”.

Moreover, identifying and reaching those most at risk can be an impossible task, particularly in countries where most people have low incomes or work in the informal economy. In Lebanon, where the UN estimates that over 80 percent of the population lives in multidimensional poverty, the primary non-contributory social security program targets “the poorest and most vulnerable families,” identified via a proxy-means tests that assigns households a score based on over 40 variables including income, assets, and demographic characteristics correlated with poverty. Social policy experts and the UN have criticized this method for its high error rates, excluding hundreds of thousands of households from social security.

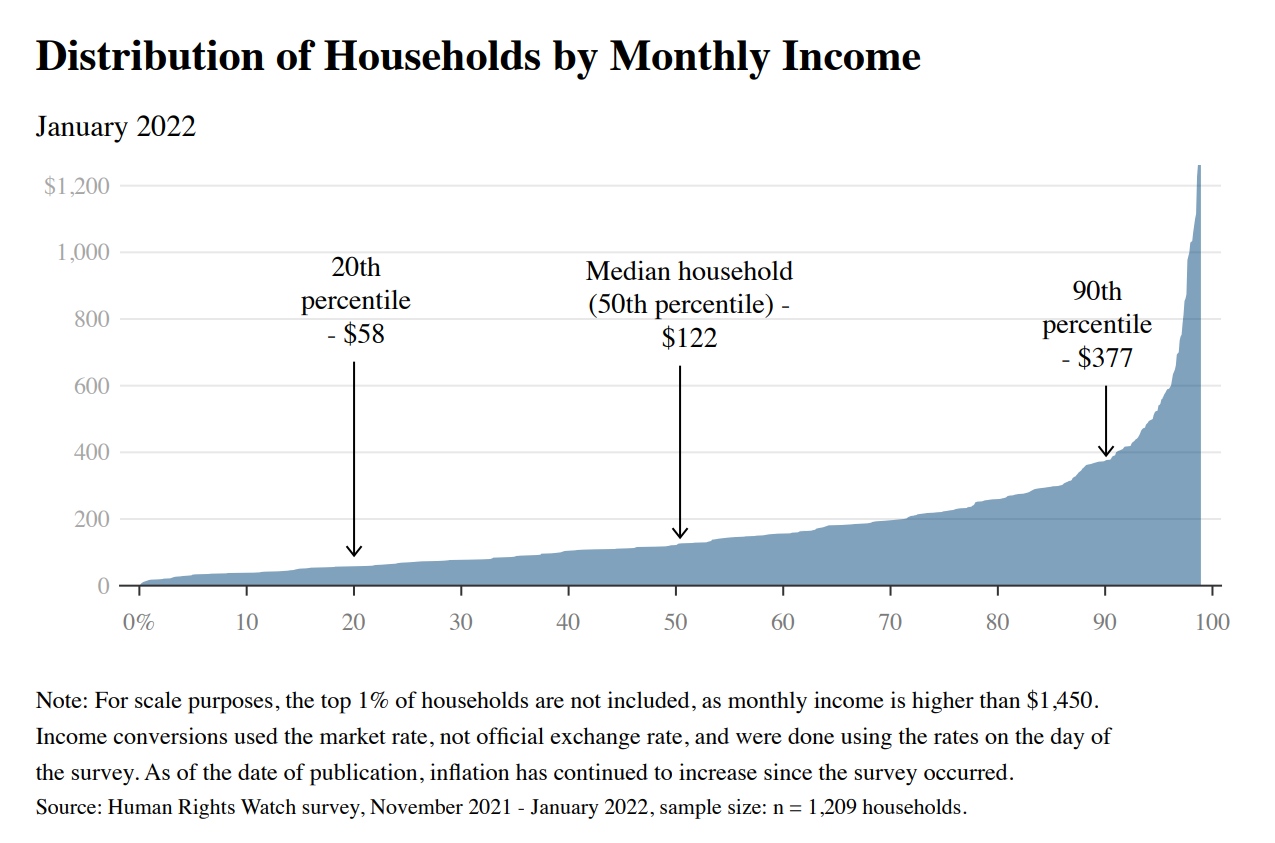

As illustrated in Graph 2, in January 2022 Lebanon’s income distribution was relatively flat, turning the distribution of benefits into an error-riddled lottery-like selection process, eroding trust in a system perceived as arbitrary. Such systems not only fall short of their intended impact, but also contribute to tensions and undermining trust in already polarized societies, instead of building solidarity and social cohesion.

Graph 2 – Lebanon’s Distribution of Households by Monthly Income

Targeted systems have also been found to contribute to social stigma, which in turn creates disincentives for individuals to seek benefits they are entitled to. A review of causes for the “non-take-up” of benefits by the UN special rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights identified shame and stigma as major barriers to claiming benefits, especially when conditionalities are attached to their provision.

What cuts across targeted programs is an ideological view that sees social security not as a right, but as the minimal support provided by governments to avoid destitution among the “deserving poor.”

Universal programs offer a simpler, more transparent structure with lower administrative costs, aligning better with the universality of rights, reducing opportunities for corruption, and avoiding stigmatizing beneficiaries. Additionally, by providing benefits that are visible to all taxpayers, including the middle classes, universal programs can foster political support, ensuring the sustainability of social security over time, and increasing the financing capacities.

Can governments pay for universal social security?

Implementing the right to social security is affordable and redistributive as long as individuals and corporations pay their fair share in taxes and social insurance contributions.

Under international human rights law, states are obliged to take steps to the maximum of their available resources to progressively realize rights, including the right to social security. The committee charged with interpreting the ICESCR has emphasized that although realizing the right to social security has “significant financial implications for States parties […] the fundamental importance of social security for human dignity and the legal recognition of this right by States parties mean that the right should be given appropriate priority in law and policy”.

The committee further noted (para. 13) that governments can expand fiscal space for social security, even in the poorest countries. This can be achieved through the reallocation of public expenditure, increasing tax revenues, reducing debt or debt servicing, adapting the macroeconomic framework, fighting illicit financial flows, and increasing social security revenues.

Raising additional revenue to fund social security is not a zero-sum matter. It can help build trust in the government by demonstrating that it cares for its people and helps them weather challenging economic times. This, in turn, encourages people to contribute through taxes, resulting in higher government revenues. It also serves as an economic catalyst, as evidenced by the International Trade Union Confederation, which found that social security investments of 1 percent of GDP yield multiplier effects ranging from 0.7 to 1.9.

According to ILO estimates, the global financing gap for social security amounts to about three percent of global GDP. Closing this gap sustainably demands a substantial share to be shouldered by national resources. Experiences from countries at various income levels show that implementing universal programs to address this gap is feasible everywhere. A case in point is Nepal, which initiated a universal pension in the 1990s, later introducing universal disability benefits. These popular programs remain on the political agenda, ensuring their continuity and contributing to increased benefit values over time.

At a time when the world is in the grip of an inequality crisis, the global community should renew its commitment to making the right to social security a reality. Embracing the universality of this right and expanding the required fiscal space is not only feasible, but also urgently needed.