Summary

Maciré Camara, a widow and mother of five, is a farmer in Diakhabia, a village in the Boké region of Guinea, West Africa.[1] Walking through Camara’s community, it’s hard to imagine the connection between the global car industry and her rural village, where most of the vehicles are beat-up taxis used to ferry people to nearby towns.

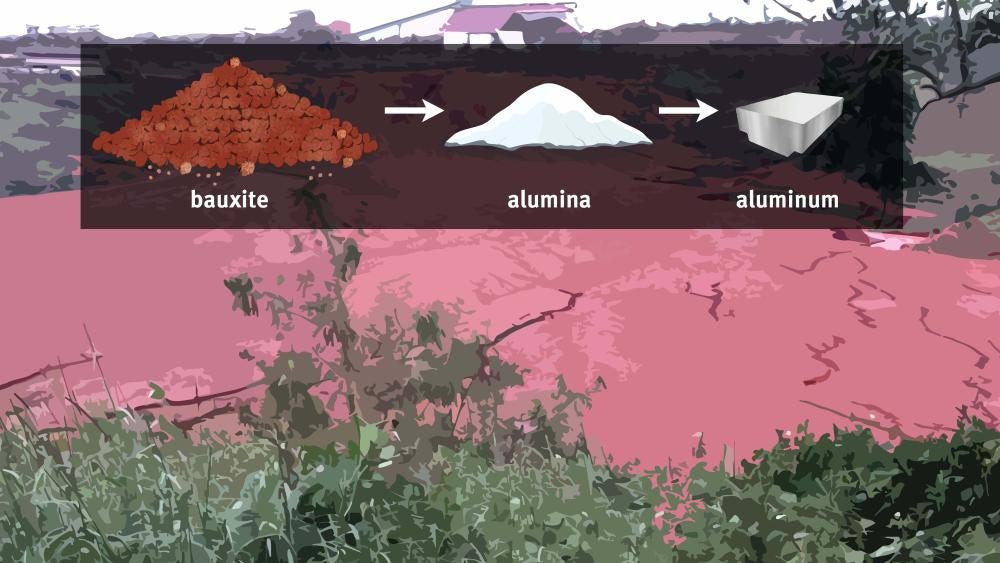

Guinea is at the center of an extraordinary boom in bauxite mining, the ore used to make aluminum, a lightweight metal that is a key component of fuel-efficient vehicles. Guinea has the world’s largest bauxite deposits and has rapidly expanded production, growing its global market share from 4 percent in 2014 to 22 percent in 2020. Guinea is now the biggest exporter of bauxite to refineries in China, which produces the majority of the world’s aluminum. Bauxite is also mined in Australia, Brazil, India, and several other countries.

Car manufacturers are major industrial consumers of aluminum, using 18 percent of all aluminum consumed worldwide in 2019, according to the International Aluminum Institute (IAI), an industry group. As car companies transition to electric vehicles, the IAI forecasts that the industry’s demand for aluminum will double by 2050. Aluminum is highly recyclable, but more than half the aluminum used by the car industry is primary aluminum produced from bauxite.

The aluminum industry portrays aluminum as a key material for the transition to a more sustainable world, with the European Aluminum Association, an industry group, saying in a 2018 video that, “The future of mobility is electric…and the metal enabling this green electric future is aluminum.” This image, however, contrasts sharply with the experience of communities, like Camara’s, for whom bauxite mining has had a devastating impact on their way of life.

Prior to the arrival of mining, Camara’s family relied on farming for food and income, planting rice and other crops on the fertile land on the banks of the nearby Rio Nunez river. She could just about afford enough food for her children, earning up to 1.5 million Guinean francs (US$152) per week during a good harvest season and taking home around 10 million Guinean francs per year ($1,010).

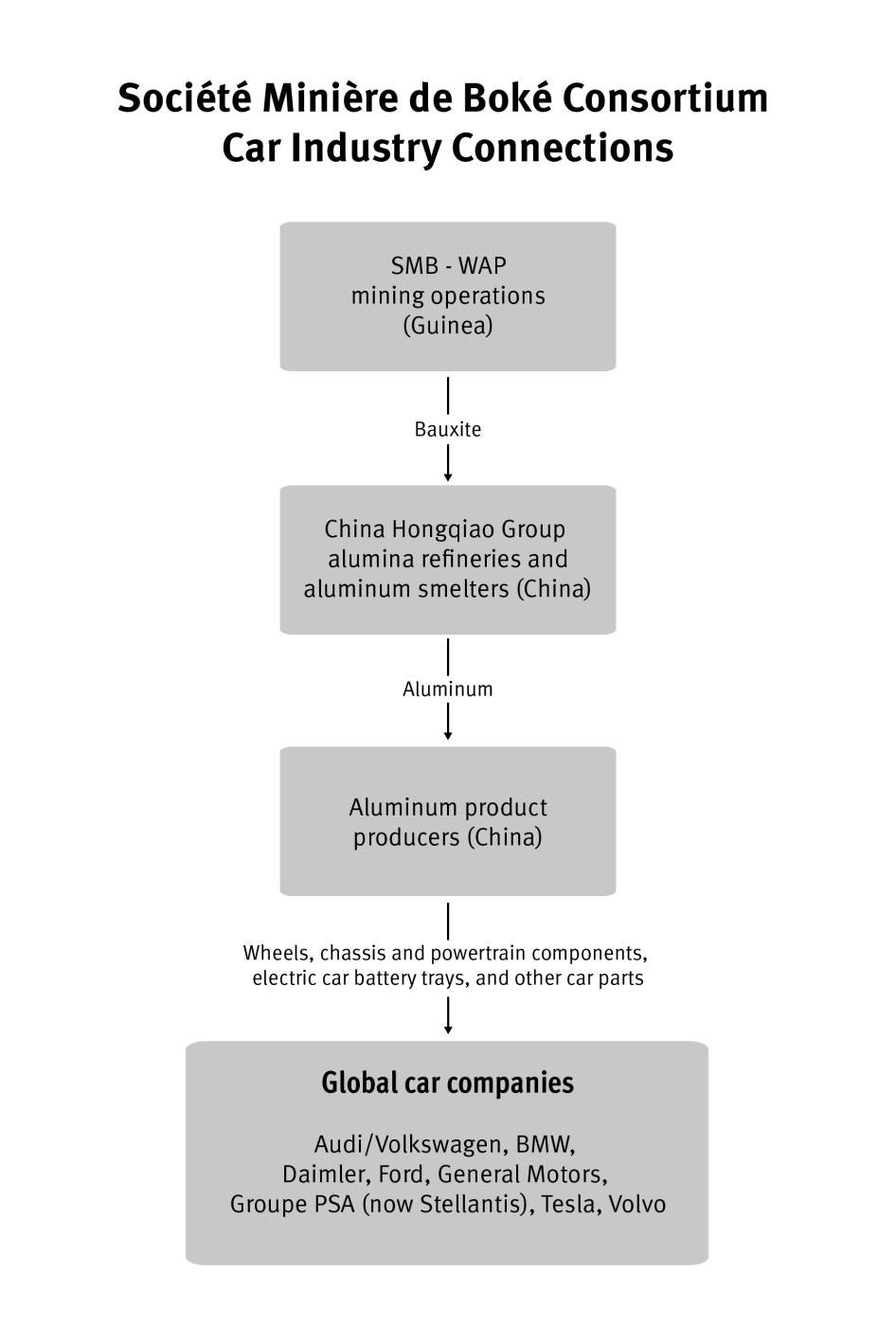

Things changed in 2016 when a consortium linked to La Société Minière de Boké (SMB), Guinea’s largest bauxite mining company, began clearing hundreds of hectares of land around Diakhabia to make way for an industrial port. Since 2017, the port has been shipping millions of tons of bauxite each year to refineries belonging to China Hongqiao, the largest aluminum producer in the world. China Hongqiao and other companies who source bauxite from Guinea make aluminum that is eventually turned into components used by some of the world’s largest car companies.

Camara’s family was among the dozens of households in Diakhabia who lost land to the port. The mining consortium paid Camara compensation of just over 4 million Guinean francs ($406) in 2016, a one-off payment that could not replace the land that her family depended on for its livelihood. More than four years later, and without land to farm, Camara has been thrust further into poverty. “I’ve only been able to find half a hectare of land to farm, and I make about 3 million Guinean francs ($303) per year,” she said in December 2020. “We used to eat three meals a day, but now we sometimes have to make do with one or two.” SMB told Human Rights Watch that its projects are audited annually by the Guinean government to verify its respect for human rights and the environment and that it pays fair compensation for the land it acquires.

Camara’s story is just one example of the profound impact that aluminum production around the world can have on the rural communities that live closest to mining and refining operations.

Bauxite mines, because they involve surface level or “strip” mining, take up a large area, often covering land that has significant ecological value and that local communities depend on for their livelihoods. In Australia, bauxite mining has for decades occurred on land belonging to Indigenous Peoples, many of whom are still fighting for adequate restitution.

Bauxite mining can also contaminate rivers and streams by removing vegetation and facilitating erosion, reducing the quality and quantity of water available to nearby communities. In Ghana, a coalition of civil society and local citizens’ groups say that a planned bauxite mine in the Atewa rainforest threatens to contaminate rivers that provide drinking water to millions of people.

The process of refining bauxite into alumina, an intermediate product then converted to aluminum, also has significant potential environmental and human rights impacts. Alumina refining produces large amounts of red mud, a highly caustic material that, unless stored properly, can pollute waterways and harm people who come into contact with it. In Brazil’s Pará State, a nongovernmental organization representing more than 11,000 people, including Indigenous People and Afro-Brazilians, has several ongoing legal complaints against Norsk Hydro, which operates a bauxite mine, refinery, and aluminum smelter, over the alleged contamination of waterways in the Amazon basin. Norsk Hydro told Human Rights Watch that it respects the claimants’ right to file the lawsuits and will respond based on the facts and evidence presented in court.

Aluminum production also generates significant amounts of greenhouse gas emissions, with the majority of the electricity used to convert alumina into aluminum, an energy intensive process, currently generated by coal power plants. In China, which dominates global aluminum production, 90 percent of aluminum was produced with electricity from coal power in 2018. Aluminum production is responsible for more than one billion tons of CO2 equivalent annually—around two percent of global greenhouse gas emissions.

This report, a collaboration between Human Rights Watch and Inclusive Development International, argues that, given the reliance on aluminum of the global automobile industry, car companies have a responsibility under the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights to address the human rights and environmental impacts of aluminum production.

The report begins by setting out the human rights consequences of the aluminum industry, using examples from around the world and an in-depth case study of bauxite mining in Guinea, based on extensive field and remote research from 2017 to 2020. The report then discusses the car industry’s current efforts to source aluminum responsibly, drawing on meetings or correspondence with nine car companies: BMW (headquartered in Germany), Daimler (Germany), Ford (United States), General Motors (United States), Groupe PSA (France, now part of Stellantis group), Renault (France), Toyota (Japan), Volkswagen (Germany), and Volvo (Sweden). Three companies, BYD (China), Hyundai (South Korea), and Tesla (United States), did not respond to requests for information. By combining field-driven examples of communities’ experience of aluminum production with dialogue with car companies about their ability to respond, this report makes a compelling case for the car industry to do more to protect communities like Camara’s from the negative impacts of the aluminum industry.

Aluminum Sourcing is a Blind Spot for the Car Industry

Many of the world’s leading car companies have human rights due diligence policies that commit them to identifying and mitigating human rights abuses in their supply chains. However, despite the increasing importance of aluminum to the automobile industry, the human rights impact of aluminum production – and bauxite mining in particular – remains a blind spot.

Although car companies’ knowledge of aluminum supply chains varies, none of the nine companies that responded to Human Rights Watch and Inclusive Development International had, prior to being contacted for this report, mapped their aluminum supply chain to understand the human rights risks within it. Car companies have instead prioritized supply chain due diligence for other materials central to electric vehicles, such as the cobalt needed for electric batteries, with several car industry executives underscoring the need for consistency between the transition to environmentally friendly vehicles and responsible sourcing.

Although the car industry as a whole has made limited efforts to source aluminum responsibly, several car companies, Audi, BMW, and Daimler, have sought to promote responsible sourcing by joining an industry-led certification scheme, the Aluminium Stewardship Initiative (ASI), that uses third-party audits to assess mines, refineries, and smelters against a Performance Standard that includes human rights and environmental factors. According to ASI, 11 percent of operational bauxite mines and alumina refineries and 20 percent of aluminum smelters are currently certified against the Performance Standard. Volkswagen, BMW, and Daimler are encouraging aluminum producers to join ASI and expand the amount of certified aluminum available for purchase.

ASI’s standards and audit process, however, need significant strengthening. ASI’s human rights standards, which are currently being revised, need to provide increased protection for communities who lose land to mining, particularly those with customary land rights. More broadly, the human rights requirements in ASI’s standards lack adequate detail and do not break down key human rights issues, such as how to resettle communities displaced by mining, into specific criteria against which companies’ policies and practices can be assessed. ASI’s process for verifying whether companies meet its standards also need to provide stronger guarantees for participation from communities in the audit process and should ensure that published audit reports state clearly whether and how a facility met ASI’s standards. In the absence of clear requirements for participation from communities in ASI’s audits, and more transparency in audit reports, they provide little reassurance about whether and how a company is respecting human rights on the ground.

BMW and Daimler said ASI should consider aligning its standards and assurance process more closely with another mining certification scheme, the Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance (IRMA). Human Rights Watch is a member of IRMA’s board. IRMA has more detailed human rights standards, clearer guidance on how to involve communities in audit reports, and has so far provided more detail in its published audit reports. Fiona Solomon, ASI’s Chief Executive Officer (CEO), said that as part of its standards revision, ASI is, “enhancing guidance for auditors on consultation with, and outreach to, affected communities.” She also said that IRMA and a range of other standards were being reviewed as part the standards revision.

Car companies should also understand that sourcing certified aluminum does not on its own fulfill their responsibility to address human rights risks in supply chains. Certification schemes rely on third-party audits that research has shown have significant limitations, including inadequate consultation with affected communities and lack of human rights expertise among auditors. Sourcing certified aluminum should only ever be one part of a broader due diligence process that includes supply chain mapping and public disclosure, risk analysis, grievance mechanisms, and direct engagement with mines, refineries, and smelters implicated in human rights abuses.

Some car companies have, since being contacted by Human Rights Watch and Inclusive Development International, begun to take these steps. Drive Sustainability, a coalition of 11 car companies that includes BMW, Daimler, Ford, Toyota, Volkswagen, and Volvo, in May 2021 initiated a project to assess the human rights risks inherent in aluminum supply chains and those of nine other raw materials, which it said could presage collective action by the autoindustry to drive up standards in supply chains. Other companies, including Renault, have also begun dialogue with their suppliers about human rights risks in the aluminum industry. In January 2021, Drive Sustainability also wrote to The Aluminum Association, an association of dozens of aluminum producers, in order “to express concern about the situation in Guinea,” to solicit information on members’ human rights due diligence efforts, and to express support for an ongoing mediation between a Guinean mining company and 13 impacted communities. In November 2020, BMW Group stated that, if bauxite mining in Ghana’s Atewa Forest violated the government’s commitments to fight climate change and protect biodiversity, BMW would not accept aluminum originating from the forest in its supply chain.

What the Car Industry Should Do Next

These positive steps should be the start of a wider effort by car companies to address the human rights impacts of aluminum production. Car companies should begin by ensuring that binding human rights and environmental standards are integrated into their procurement contracts and should require suppliers to integrate similar language into contracts throughout the supply chain.

Car manufacturers cannot, however, rely only on their suppliers to enforce human rights and environmental standards. All car manufacturers should make aluminum a priority raw material for responsible sourcing and should map their aluminum supply chain to identify the mines, refineries, and smelters they are sourcing from. Car companies should then disclose this information to enable communities and NGOs to share information on human rights risks.

Having mapped their supply chains, car companies should regularly assess any adverse human rights impacts through robust third-party audits at mines, refineries, or smelters, as well as through dialogue with NGOs and civil society groups. Third-party audits should be designed in consultation with a variety of stakeholders, including civil society and affected communities, and should empower affected populations to participate without fear of retaliation. Car manufacturers should also conduct visits to bauxite mines, alumina refineries, and aluminum smelters and meet with impacted communities at these sites.

Car companies should then formulate a plan for mitigating and addressing human rights abuses in their aluminum supply chains. This should include engagement with mines, refineries, or smelters implicated in human rights violations to require them to develop time-bound corrective action plans and provide remedies for victims. Where facilities do not take adequate corrective action over a reasonable period of time, car manufacturers should reject aluminum parts sourced from the facility in question and require their suppliers to terminate procurement relationships with the facility.

Car companies should also consider whether to take collective action, in collaboration with civil society groups and other key stakeholders, to address human rights risks common to bauxite mining, alumina refining, or aluminum production in a given country or region. This could include, for example, an effort to audit multiple mining companies in the region to compare practices and identify common areas for improvement.

Finally, car companies should develop grievance mechanisms through which communities can file complaints of human rights abuses by bauxite mines or aluminum producers in their supply chains. Car manufacturers should also support the development of laws requiring all business actors to conduct robust human rights due diligence, creating a level playing field across the industry and increasing their suppliers’ incentive to respect human rights.

The story of Camara and her community in Guinea is still unfolding. The SMB consortium that operates the port near her village has the right to mine in the area until at least 2031, and there is enough bauxite for mining to continue in the Boké region far beyond that. Camara’s experience with mining so far reflects the huge power imbalance between communities affected by bauxite mining and multinational mining companies. By lending their weight to efforts to drive up human rights standards in the aluminum industry, car companies can help provide a more hopeful future for Camara’s community and others like it.

Methodology

This joint report by Human Rights Watch and Inclusive Development International advocates for strengthened efforts by the global car industry to address the human rights impact of aluminum production, particularly the mining and refining of bauxite, the ore needed to produce aluminum. Aluminum is a key material for the transition to lighter and more environmentally friendly vehicles, particularly electric cars.

Human Rights Impact of Aluminum Production

This report’s description of the human rights impact of aluminum production draws on desk research on the impacts of the industry worldwide, including a review of material published by industry groups, NGOs, and journalists. The report then uses a detailed case study of bauxite mining in Guinea, which has the world’s largest deposits and is the second largest producer, to illustrate the industry’s human rights impacts. The chapter on Guinea focuses in particular on two mining companies, La Société Minière de Boké (SMB) and La Compagnie des Bauxite de Guinée (CBG), that together made up more than 70 percent of Guinea’s bauxite exports in 2019 and almost 60 percent in 2020.

The findings on Guinea are based on extensive research by Human Rights Watch and Inclusive Development International. Human Rights Watch conducted more than six weeks of field research in mining-affected areas in Guinea between 2017 and 2019, and published a 145-page report in 2018. During 2020, and in the course of the Covid-19 pandemic, Human Rights Watch conducted 18 telephone interviews with community members in mining-affected areas and with NGO representatives, mining executives, and journalists active in Guinea’s mining sector. Human Rights Watch’s findings on Guinea’s mining sector are also informed by satellite imagery analysis, review of environmental and social impact assessments and government and company audits, and correspondence and interviews with government officials and company executives.

Inclusive Development International has also conducted extensive research and advocacy in Guinea. In February 2019, Inclusive Development International, along with Guinean NGOs, filed a complaint on behalf of 13 villages affected by CBG’s operations against the International Finance Corporation (IFC), a World Bank body, for lending the company US$200 million to expand its mining operations. CBG and the communities are now engaged in a mediation process facilitated by the IFC’s Compliance Advisor Ombudsman to try to resolve the communities’ grievances. Inclusive Development International and two Guinean NGOs are accompanying the community representatives in the mediation process.

Prior to filing this complaint and subsequently, Inclusive Development International and Guinean NGOs conducted extensive fact-finding to document the impacts of CBG’s mining operations on local communities. This included in-person interviews, group discussions, participatory resource mapping with 17 CBG-affected villages and an analysis of satellite imagery from 1973-2019.

Despite the Covid-19 pandemic, Inclusive Development International has remained in close and frequent contact with the 13 communities involved in the complaint against CBG, speaking regularly to community representatives and conducting field research to reflect recent impacts from the mine’s expansion activities in 2020.

Human Rights Watch wrote to SMB and CBG in May 2021 informing them about the publication of this report and requesting updated information on their human rights, environmental, and social practices. Human Rights Watch also had a virtual meeting with CBG in June 2021. SMB and CBG responded with letters in June 2021 and Human Rights Watch subsequently wrote to SMB and CBG again requesting supplemental information, including comments on supply chain mapping. At time of writing, Human Rights Watch had not received an additional response.

In May 2021, Human Rights Watch wrote to the Guinean Ministry of Mines and Geology requesting responses to questions about the government’s oversight of Guinea’s bauxite mining sector. The ministry replied in June 2021. Copies of all the letters from CBG, SMB, and the Guinean government are available on Human Rights Watch’s website.

Aluminum Sourcing and the Car Industry

This report’s research on car companies’ aluminum sourcing included supply chain mapping and research on the car industry’s efforts to integrate human rights due diligence into their sourcing practices.

To demonstrate the connections between bauxite mining, aluminum production, and the global car industry, Inclusive Development International conducted a detailed investigation to examine the supply chain that links bauxite produced in Guinea, the main case study for this report, and the aluminum parts used by global car companies. The investigation, which was conducted from 2017 to 2019, used publicly available sources such as company financial disclosures, import-export data, shipping records, and media reporting.

Between May and October 2020, Human Rights Watch and Inclusive Development International conducted a desk review of car companies’ existing human rights due diligence and responsible sourcing efforts, reviewing car companies’ published materials describing their sourcing and sustainability practices and reports written by NGOs and industry groups. We then wrote to 12 car companies to ask them what steps they take to responsibly source aluminum. We identified the car companies based on factors that included their overall share of global car sales; their share of global electric vehicle sales; and a desire for geographic diversity in the companies that we targeted.

Human Rights Watch and Inclusive Development International ultimately met with representatives of seven of the 12 companies contacted ahead of the publication of this report: BMW (headquartered in Germany), Daimler (Germany), Ford (United States), General Motors (United States), Groupe PSA (France, now part of Stellantis group), and Renault (France), and Volkswagen (Germany). Toyota (Japan) and Volvo (Sweden) responded in writing to our letter. We received no reply from BYD (China), Hyundai (South Korea), or Tesla (United States).

As part of the research, we also spoke with several aluminum and automotive industry groups, including Drive Sustainability, a coalition of 11 car companies that includes BMW, Daimler, Ford, Toyota, Volkswagen, and Volvo; the International Aluminum Association, an aluminum industry group; and the Aluminum Stewardship Initiative (ASI), the leading certification scheme in the aluminum sector. We wrote to ASI in April 2021 to provide comments on proposed revisions to their standards. In June 2021, we also shared preliminary findings of this report with ASI. ASI provided comments during meetings in June 2021 and also provided a written response.

Aluminum and the Car Industry

Aluminum is a light weight but strong metal produced from bauxite, a red ore.[2] Bauxite deposits are found in Guinea, which has the world’s biggest deposits, in Australia, currently the biggest producer, and in other countries including Brazil, China, India, Jamaica, and Vietnam.[3] Primary aluminum is produced through a refining process in which bauxite is converted to an intermediate product, alumina, and then smelted into aluminum.[4] As a general rule, four tons of dried bauxite is required to produce two tons of alumina, which in turn produces one ton of aluminum.[5] Some but not all aluminum producers are “vertically integrated,” meaning that they operate or co-own their own mines, refineries, and aluminum smelters.[6]

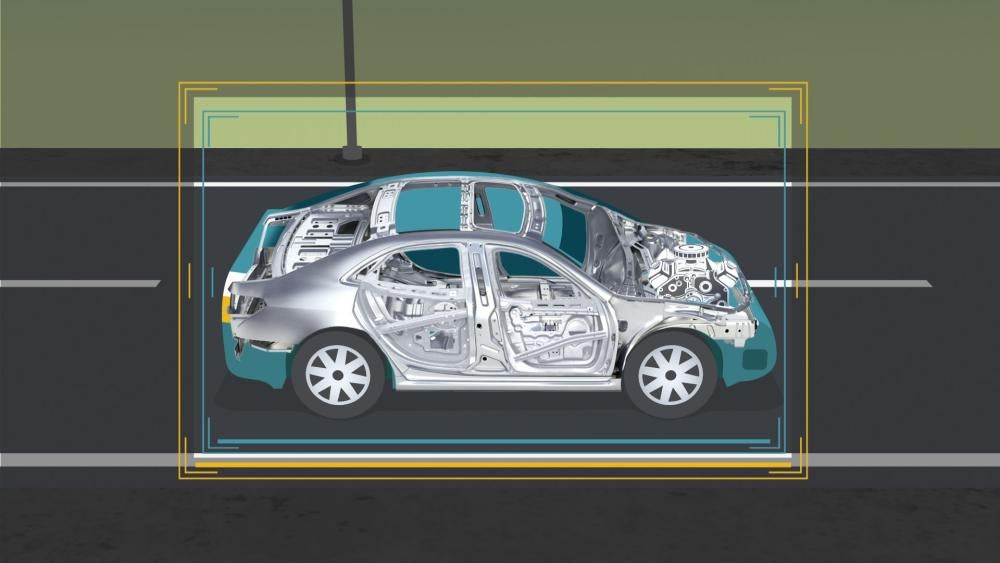

The car industry is a major industrial user of aluminum, consuming 18 percent of all aluminum consumed worldwide in 2019.[7] Although aluminum usage varies by car brand, manufacturers currently use aluminum in parts like engines, chassis, frames, body panels, wheels, and many other smaller components.[8]

The car industry’s aluminum usage has increased dramatically as car companies have sought to make gas and diesel-powered cars lighter to increase fuel efficiency and reduce emissions.[9] One study estimated that the average aluminum content in cars in North America had grown from 84 pounds (38 kilograms) per vehicle in 1975 to 340 pounds (154 kilograms) in 2010 and an estimated 466 pounds (211 kilograms)– or 13 percent of a vehicle’s total weight – in 2020.[10]

Aluminum usage in cars will now expand further as the automobile industry races to develop electric and hybrid vehicles that can cut greenhouse gas emissions and contribute to the fight against climate change.[11] Deloitte, a consulting firm, has predicted that global sales of electric vehicles will increase from 2 million in 2018 to 12 million in 2025 and 21 million in 2030.[12]

Aluminum’s light weight makes it a key component of electric cars, with reduced weight increasing the distance electric cars can travel before being recharged.[13] Aluminum can also be used as a component of, and for the casings that surround, electric batteries.[14] European Aluminum, an industry group, said in a 2018 video that, “The future of mobility is electric…and the metal enabling this green electric future is aluminum.”[15] The International Aluminum Institute (IAI), an aluminum industry group, estimates that the car industry’s demand for aluminum will double by 2050, from almost 17 million tons in 2019 to almost 35 million tons.[16]

Aluminum is highly recyclable and producing recycled aluminum – known as “secondary” aluminum – is more energy efficient and results in less waste material than producing “primary” aluminum from bauxite.[17] Primary aluminum, however, accounts for the majority of aluminum produced worldwide, accounting for 66 percent of aluminum in 2019 compared to 34 percent recycled material.[18] The IAI estimates that 42 percent of the aluminum used by the car industry is recycled and 58 percent comes from primary aluminum.[19] The IAI has forecast that even by 2050 primary aluminum will still constitute 50 percent of aluminum produced globally, and approximately 45 percent of the aluminum used by the car industry.[20]

The Human Rights Impact of Aluminum Production

Loss of Land to Mining

Bauxite mining, because it occurs at the surface level, requires access to large tracts of land, often forcing the resettlement of homes or villages, reducing access to farm and pasture land, and threatening communities’ access to housing, food, and the right to an adequate standard of living.[21]

Bauxite mining in Australia has for decades occurred on land belonging to Indigenous Peoples, who were historically forcibly displaced from or dispossessed of their ancestral lands.[22] Although Australia, beginning in the mid-1970s, strengthened protection for the land rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, many are still fighting for restitution for past land seizures, redress for damage caused to their lands, and for their right to exercise control over and fully benefit from natural resource extraction on their land.[23]

In Guinea, as discussed in more detail below, a bauxite mining boom is occurring in areas occupied by communities that have ancestral customary land rights. A Guinean Ministry of Mines commissioned study estimated in 2019 that over the next 20 years bauxite mining will eliminate 858 square kilometers of agricultural land and more than 4,700 square kilometers of natural habitat, an area six times bigger than New York City.[24] Guinean families, who are often dependent on subsistence agriculture, frequently do not receive replacement land or adequate compensation from mining companies, which means land loss deprives them of their economic base and risks plunging them further into poverty.[25]

Reduced Access to Water

Unless managed appropriately, bauxite mining can produce significant impacts on the hydrology of the surrounding landscape, threatening access to water.[26] Surface mining can increase soil erosion, sending sediment into nearby rivers and streams, gradually blocking or obstructing their flow and reducing water quality for aquatic organisms.[27] Sediment can also bring with it aluminum, iron compounds, and naturally occurring heavy metals that can be dangerous at high concentrations, reducing access to clean water for communities.[28]

In Malaysia, images of rivers and coastal areas polluted with red sediment were a key factor in the government’s decision to ban bauxite mining for environmental reasons in January 2016.[29] The government ended the ban in March 2019.[30]

In Ghana, a coalition of civil society and local citizen groups have filed a lawsuit opposing a planned bauxite mine in the Atewa Range Forest Reserve, a biodiverse rainforest.[31] The groups argue that bauxite mining, by clearing large areas of forest, would threaten the access to food and livelihoods of local communities and affect the quality and quantity of water in three rivers that provide drinking water to millions of people.[32]

In Guinea, communities have told Human Rights Watch and Inclusive Development International that sediment from bauxite mines and mining roads has reduced water quantity and quality in local rivers, streams, and wells that they rely on for washing, cooking, and drinking.[33]

Impacts from Alumina Refining

In countries that refine bauxite into alumina before export, refineries are often located near bauxite mines to enable efficient transport of bauxite to the refinery.[34] Alumina refineries bring with them additional and potentially very significant environmental and human rights impacts. The refining process, for example, produces very large amounts of a caustic by-product, known as “red mud,” with 1 to 1.5 tons of red mud produced for every 1 ton of alumina.[35] Red mud is highly alkaline and contains compounds, including iron and metallic oxides, that can be harmful to local ecosystems.[36] If not stored safely it can contaminate surrounding waterways and cause harm to people who come into contact with it.[37]

The failure of a dam used to store red mud in Hungary in October 2010 flooded more than 250 homes, killing at least 10 people and injuring 150, some of whom were burnt by the caustic mud through their clothes, according to media reports.[38] In Brazil’s Pará State, a nongovernmental organization representing more than 11,000 people, including Indigenous People and Afro-Brazilians, has several ongoing legal complaints against Norsk Hydro, which operates a bauxite mine, a refinery and an aluminum smelter, over the alleged contamination of waterways in the Amazon basin.[39] Norsk Hydro told Human Rights Watch that it respects the claimants’ right to file the lawsuits and will respond “based on the facts and evidence as requested before the court.”[40]

Aluminum and Climate Change

Production of primary aluminum, and particularly the smelting of alumina into aluminum through electrolysis, is very energy intensive. [41] Each year, aluminum production is responsible for about one billion tons of CO2 equivalent or around two percent of global greenhouse gas emissions.[42] Producing recycled or secondary aluminum requires about one tenth of the energy of primary aluminum production.[43]

The aluminum industry’s high carbon footprint is in large part due to the industry’s reliance on coal power. Globally, 71 percent of electricity generated for aluminum comes from fossil fuels, more than 60 percent from coal-fired power plants.[44] China’s aluminum smelters, which produce more than half of the world’s primary aluminum, are particularly reliant on coal, with 90 percent of Chinese aluminum produced with electricity from coal power plants in 2018.[45] Many of China’s major aluminum producers have built and operate their own coal-fired power stations, outside of China’s electricity grid, with approximately 75 percent of the energy used for China’s aluminum industry self-generated.[46]

Case Study: Bauxite Mining in Guinea

Guinea’s Bauxite Boom

Guinea is a small, resource-rich country in West Africa, with a population of approximately 13.1 million people.[47] Guinea possesses the world’s largest reserves of bauxite – the ore needed to make aluminum – with more than one-third of the Earth’s known deposits. [48] Guinea also has large deposits of iron ore, gold, and diamonds.[49]

Mining has long been a major contributor to the Guinean economy, with a World Bank report in August 2020 stating that mining accounts for 15 percent of Guinea’s gross domestic product and 20 to 25 percent of government revenues.[50] But despite its abundant mineral wealth, Guinea remains one of the world’s poorest countries, ranking 174 of 189 states in the 2019 Human Development Index.[51]

Guinea’s bauxite sector has grown rapidly since 2015, with foreign investment in bauxite mining in the Boké region totaling $5 billion since 2015, according to the World Bank.[52] Demand for Guinean bauxite in global markets sharply increased as other countries, notably Indonesia in 2014 and Malaysia in 2016, banned bauxite exports.[53] Guinea is now on its way to becoming the world’s largest bauxite producer, growing its global market share from 4 percent (17 million tons) in 2014 to 22 percent (82 million tons) in 2020.[54] Guinea is already the biggest exporter of bauxite to refineries in China, which in 2020 despite mining just 16 percent of global bauxite produced more than 56 percent of primary aluminum.[55] Guinea’s share of the global bauxite market is likely to grow further in the next few years, with the Guinean government aiming to produce at least 100 million tons

per year.[56]

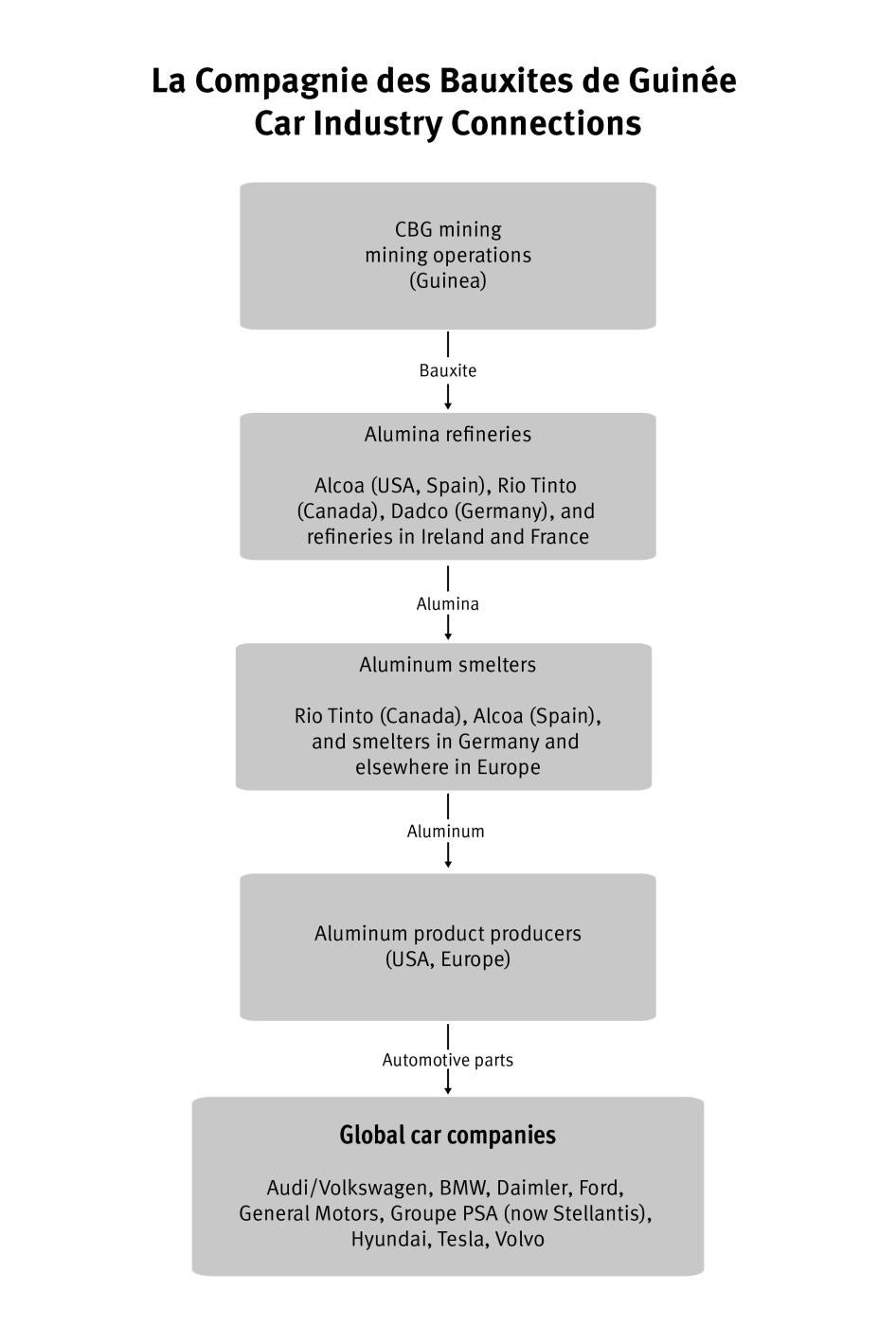

La Société Minière de Boké (SMB) and La Compagnie des Bauxite de Guinée (CBG), the two companies examined in this report, made up more than 70 percent of Guinea’s bauxite exports in 2019 and almost 60 percent in 2020.[57] SMB is a consortium bringing together the world’s largest aluminum producer, China Hongqiao Group, which operates its own alumina refineries and aluminum smelters in China, as well as a Singaporean shipping company, Winning International Group, and a Guinean logistics company, United Mining Services International.[58] CBG is a joint venture co-owned by the Guinean government and multinational mining companies Rio Tinto, Alcoa, and Dadco.[59]

Guinea’s Role in Global Supply Chains

The expansion of bauxite mining in Guinea means that it is playing an increasingly significant role in global aluminum supply chains. In addition to China, bauxite from Guinea is also shipped to refineries in Canada, France, Germany, Ireland, Russia, Spain, and the United Arab Emirates.[60] Guinea itself refined less than 1 million tons of the 82 million tons of bauxite it produced in 2020, although Guinea’s government aims to expand the country’s refining capacity in the next few years.[61]

To explore in detail the connections between Guinea’s mining industry and the global car industry, Inclusive Development International traced how the bauxite produced by CBG and SMB flows through global supply chains. CBG and SMB have mining permits running until at least 2040 and 2031, respectively, meaning they, like other bauxite mining companies in Guinea, are likely to contribute to global supply for many years.[62]

Inclusive Development International’s supply chain investigation, which was undertaken from 2017 to 2019, used open-source data such as company filings, import-export data, shipping records, and other public reporting to trace bauxite from Guinea to the supply chains of aluminum companies operating globally.

In the case of CBG, the investigation found that the bulk of the company’s bauxite is shipped to alumina refineries and aluminum smelters in North America and Europe that belong to CBG’s co-owners, Rio Tinto, Alcoa, and Dadco.[63] The aluminum is then converted into semi-industrial aluminum products used by industrial manufacturers, including suppliers of many of the world’s leading automobile brands. The graphic below illustrates key features of CBG’s supply chain based on supply chain mapping from 2017 to 2019.

SMB’s bauxite takes a different route. The bauxite is shipped to China and bought, refined, and smelted by facilities owned by the China Hongqiao Group, a member of the SMB consortium.[64] China Hongqiao’s refineries and smelters, which produce the largest amount of primary aluminum in the world, get the majority of their bauxite from SMB’s Guinean mines.[65] Aluminum produced by China Hongqiao is used by industrial manufacturers in China that supply parts to many of the world’s biggest car companies.[66] China Hongqiao, in its 2020 annual report, noted that, “with energy savings, reduced emissions and low carbon footprints being strongly advocated by society, aluminum for...lightweight aluminum for motor vehicles [is] expected to become key consumption growth for the aluminum processing industry.”[67] The graphic on the next page illustrates key features of SMB’s supply chain based on supply chain mapping from 2017 to 2019.

The Human Rights Impact of Bauxite Mining in Guinea

The Boké region, in northwestern Guinea, has been at the center of the bauxite sector’s recent growth. Government figures estimated the region’s population at 1.3 million people in 2020.[68] Like other parts of Guinea, the region has high levels of poverty, with a 2014 census finding that 73 percent of its population, and 86 percent in rural areas, live in poverty, which the census defined according to a range of criteria evaluating a person’s living standards and access to health and education.[69]

Boké is highly dependent on agriculture, with government data stating that, in 2014 to 2015, more than 890,000 people in the region, or approximately 80 percent of the population, relied on agriculture for their livelihoods.[70] Most farmers live in rural villages surrounded by land that has been cultivated by their families or communities for generations. Many rural villages also source water from wells or natural water sources, although they often struggle to find clean and reliable drinking water.[71]

The expansion of bauxite mining in the Boké region has significant potential economic benefits, with an October 2020 World Bank report on Guinea’s economy stating that, “mining sector growth can potentially act as a critical catalyst for local economic development.”[72] Guinea’s mining ministry, in a June 2021 letter to Human Rights Watch, said that mining decreases poverty in mining areas and noted that mining companies are required to devote a portion of their revenue to the development of local communities.[73]

In the rural communities in Boké where Human Rights Watch and Inclusive Development International have conducted research, however, residents have often described a different experience. Families describe how mining is destroying the land that they have relied on for generations and harming the natural environment they depend on for their food and livelihoods.[74] The World Bank’s October 2020 report stated that, “there are tensions among local communities in the Boké region, which often lack access to basic services (water, electricity), and do not perceive sufficient local benefits from the expanding mining industry.”[75] An earlier 2017 assessment by the Bank had concluded that, “it is urgent to mitigate the [mining] industry’s negative environmental impacts, dramatically improve its contribution to socioeconomic welfare and for the country to invest in more sustainable, diversified, and inclusive economic activities.”[76]

Land Lost to Mining

Rural land in Guinea is typically organized under customary (i.e. traditional) systems and laws.[77] A 2001 government land policy called for the formalization of customary rights to land, but has not been adequately implemented, leaving most rural land unregistered and vulnerable to transfer by the state or acquisition by private enterprises.[78] International human rights standards protect individuals and communities, including those with customary land tenure, from forced eviction and arbitrary interference with their rights to property and land.[79] Land acquisitions for mining, whether permanent or temporary, should only occur either through legally authorized processes for involuntary land acquisition or on terms agreed to by customary landholders. Individuals and communities should in all cases receive the payment of fair compensation, the provision of equivalent replacement land, and support for re-establishing livelihoods.[80]

In Guinea, however, mining companies have taken advantage of the lack of legal registration of rural land rights – and the challenges Guineans face in claiming their legal rights in the courts – to arbitrarily determine if and how they compensate families for their land.[81] The Guinean mining ministry, in a June 2021 letter to Human Rights Watch, said that land acquisitions by mining companies occur, “following an agreement negotiated between the landowner and the mining company with the assistance of government officials and local authorities according to international best practices.”[82] In reality, however, the dozens of interviews that Human Rights Watch and Inclusive Development International have conducted across the Boké region suggest that communities have little influence as to the amount and type of compensation they receive – which are determined by the mining company in question and approved by the government – and have little choice but to accept the payment offered.[83] Communities frequently neither receive adequate replacement land or compensation for land nor adequate support obtaining alternative livelihoods.[84]

The practices of CBG and SMB illustrate the approach that companies take towards communities’ land rights. Since it began exporting bauxite in 1973, CBG has progressively excavated and mined large tracts of farmland surrounding the town of Sangaredi, where its mining operations are concentrated.[85] In 2019, participatory mapping of land use conducted by local communities, Guinean NGOs, and Inclusive Development International, supported by satellite imagery analysis, found that 17 villages had lost at least 80 square kilometers of farmland and grazing land to CBG since the 1980s.[86] A central issue in communities’ complaint to the IFC’s accountability mechanism concerns CBG’s failure to provide restitution in the form of equivalent replacement land and assistance to restore livelihoods that have been destroyed as a result of land loss. According to the February 2019 complaint on behalf of 13 communities:

Since commencing its operations in the region of Sangaredi, CBG has systematically minimized and negated the customary land rights of the local communities who were living there, under an organized tenure system, long before CBG arrived. In doing so, CBG, like other mining companies in Guinea, has treated rural land as state property, and ignored or negated the customary land rights of rural farmers. Adopting this interpretation of the law, CBG has acquired land without the free, prior, and informed consent of customary landowners, without following a public expropriation process, as required under national legislation, and without the payment of fair compensation.[87]

CBG said in a May 2021 letter to Human Rights Watch that it was working to update its policy for resettling or displacing communities from land and would make public the revised document in the third quarter of 2021.[88] CBG said that the revised framework, which it said was formulated with assistance of community representatives, “acknowledges customary land rights and that it commits CBG to help communities develop alternative livelihoods and access new lands where possible.”[89] CBG also said that it has begun programs to support the restoration of livelihoods affected by mining and is “committed to prepare livelihood restoration plans in all the established communities impacted by the extension of CBG’s mining operations.”[90]

SMB’s approach to land acquisitions differs from CBG but is also problematic. Since it began operating in 2015, the consortium has made one-off financial payments to farmers for their land, helping the company to acquire land quickly and expand rapidly.[91] This approach, however, has often left farmers, unused to managing or investing money, without the resources, support, or training needed to find new land or income sources.[92] International human rights and IFC standards make clear that financial compensation alone cannot replace the lasting benefits that farming communities derived from land.[93] SMB itself stated in 2018 that:

The money [paid to individuals or communities] represents a very large amount of money that can suddenly destabilize the budget of some households and villages. Experience has taught us that people receiving these sums can spend them in a way that some people consider unreasonable (lack of budgetary vision in the medium and long term; lack of investment in potential revenue-creating activities).[94]

SMB has, since 2018, landscaped new farmland in some of the communities where it operates, but a community leader said in November 2020 that the amount of replacement land falls far short of what the community needs.[95] “The company [SMB] has only landscaped one hectare of land, where 50 people can work,” said a community leader from the village of Dapilon in December 2020.[96] “That’s only a fraction of the number of people who have lost land in this area.” Satellite imagery shows that families in Dapilon, which shares the name of one of SMB’s ports, and surrounding villages, have lost at least 200 hectares (2 square kilometers) to the SMB consortium since 2016.

Human Rights Watch asked SMB in a May 2021 letter for details of the replacement land that it has provided to communities impacted by its operations, including in Dapilon specifically.[97] SMB, in a June 2021 response, did not provide any information on the amounts of replacement land it has provided, but said that its land acquisitions are conducted consistent with Guinean law and international standards and that local communities have received fair compensation.[98]

Guinea’s ministry of mines told Human Rights Watch in June 2021 that it is taking steps to strengthen the legal framework governing land rights in the mining sector. The government is drafting a reference document for how public and private institutions approach land acquisitions that will provide guidance, “on the management of the impacts of compensation and reinstallation in line with national legislation and international best practices.”[99]

Impacts on Local Environment and the Right to Clean Water

Bauxite mining in the Boké region is also having a damaging impact on many communities’ local environment, particularly their access to water. The 2019 participatory mapping exercise conducted by Inclusive Development International with local communities concluded that CBG’s operations had polluted or destroyed 91 water sources, serving 17 villages, due to sediment runoff and the development of mining infrastructure.[100] CBG said in a May 2021 letter to Human Rights Watch that in 2018 it had implemented a water management plan to protect water resources in communities, including measures to control erosion from its mining operations. CBG also said it is installing and restoring water wells in villages bordering its mines, and constructed 15 wells in 2020.[101]

Ahead of Human Rights Watch’s 2018 report on Guinea’s bauxite mining sector, dozens of people, across more than 13 villages, told Human Rights Watch that the water sources they rely on for drinking, washing, and cooking had been negatively impacted by the arrival of SMB’s mining operations.[102] “The company cut across the rivers where we get water when they dug their mining road, without giving any warning,” said a community leader from Djoumayah, a village near SMB’s Malapouya mine.[103] “Sediments and rocks…washed down from the road into the water source.” SMB told Human Rights Watch in a June 2021 letter that it has adopted a water management plan that includes measures to mitigate its impact on water, such as the redirection of water carrying sediment run-off from mining sites to reservoirs.[104] SMB also said it had, over the past three years, constructed 87 bore holes and 10 wells for local communities, as well as made annual payments to local development funds for the Boké region, including $2.1 million for 2020.[105]

Beyond the impact of individual mining projects, the cumulative long-term impacts of mining also have potentially profound repercussions for the Boké region’s environment.[106] The World Bank’s October 2020 report noted that, “managing cumulative impacts [in Guinea’s mining sector] will inevitably be beyond the scope of any individual investments, and hence will require proactive planning and monitoring capacity on the part of the government, which currently appears to be lacking.”[107]

“Everything That Made Fassaly a Village is Gone”:

|

Inadequate Government Oversight

Guinea’s government, although cognizant of the damage that mining can cause, has not done enough to require mining companies to meet strong environmental and human rights standards.[116] In SMB’s case, for example, Human Rights Watch’s 2018 report concluded that the consortium received mining permits in 2015 despite submitting environmental and social impact assessments that did not adequately assess the impacts of the project and how to mitigate them.[117] SMB said in 2018 that it had commissioned an international consulting firm to conduct new ESIAs and devise a new environmental social management plan (ESMP) for its mining sites.[118] SMB also said in 2018 that, “as soon as this study…is available it will be shared” and said it would be available on its website.[119] These ESIAs, if conducted appropriately, should have considered the impacts of SMB’s operations on local communities in the Boké region from 2015 onwards and provided recommendations on how to address them.[120]

SMB told Human Rights Watch in June 2021 that the revised ESIA and ESMP were completed by the international consultancy and approved by the Guinean government in June 2020. The consortium, however, has not yet published either document.[121] Instead, SMB said that Human Rights Watch should contact a Guinean environment ministry agency for a copy. Human Rights Watch contacted the agency in question and the agency said that it had not reviewed an updated ESIA or ESMP for SMB, which it said do not require government approval.[122] Human Rights Watch wrote to SMB again requesting a copy of the studies but did not receive a reply. CBG, in contrast, publishes all its environmental and social impact assessments on its website, and also conducts and publishes annual audits of environmental, social, and governance practices.[123]

Human Rights Watch’s 2018 report identified a range of factors underlying the Guinean government’s failure to adequately ensure mining companies are meeting strong environmental and social standards, including a lack of adequate resources in agencies providing oversight of mining companies and the government’s focus on growing the mining sector quickly instead of prioritizing environmental and social safeguards.[124] But there are also other factors potentially at play: a 2018 report co-commissioned by Drive Sustainability and the Responsible Minerals Initiative, a group of 360 companies that promotes responsible sourcing, ranked Guinea’s rule of law as “very weak” and its experience of corruption as “very high.”[125] The Natural Resource Governance Institute, an NGO, in June 2021 issued an updated Guinea chapter for its Resource Governance Index, which assesses how countries govern their mineral wealth. Guinea scored relatively highly in several areas, including in its management of mining revenue (scored “satisfactory”) and the conditions for establishing and realizing mining activities (“good), but continued to receive low marks for control of corruption (“poor”) and rule of law (“failing”).[126]

In a June 2021 letter to Human Rights Watch, Guinea’s ministry of mines stated that the government “works tirelessly for sustainable mining development” and “is putting everything in place to ensure mining and environmental laws are respected.”[127] The ministry’s letter also described a long list of reforms implemented to strengthen government oversight of the mining sector, and noted that the government in June 2021 negotiated and signed a new $65 million World Bank project to further strengthen its management of natural resources and the environment.[128]

An Urgent Need for Improvement

Added urgency to address human rights and environmental issues in Guinea’s aluminum sector comes from the prospect of a significant expansion in alumina refining, with approximately eight bauxite mining companies planning to set up alumina refineries in Guinea.[129] Guinea’s mining ministry said in a June 2021 letter to Human Rights Watch that processing bauxite inside the country, “as well as creating more value, will facilitate the development of a service economy that will supplant an economy based on extraction.”[130]

New alumina refineries, however, also risk adding to the human rights and environmental burden that Guinea’s mining sector places upon communities. A February 2021 environmental and social impact assessment (ESIA) for a planned SMB refinery in the Boké region, for example, states that the refinery will produce the electricity needed to convert bauxite into alumina using a generator supplied by coal from China.[131] Even with efforts to limit emissions, coal generators produce pollutants, such as sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides, linked to asthma, cancer, heart, and lung ailments, and neurological problems, while also emitting large quantities of carbon dioxide that contribute to global warming.[132]

SMB told Human Rights Watch in a June 2021 letter that the Guinean government had approved the ESIA for the refinery but that the company is still considering potential sources of energy.[133] The Guinean ministry of mines said in a June 2021 letter that, “the repercussions linked to the energy needs of the refinery and the means foreseen to achieve them are given particular attention by the administration, particularly measures put in place to control emissions of dust, smoke, and gas and improve air quality.”[134]

A Role for Car Industry Engagement?

Prior to publication of this report, Human Rights Watch asked the Guinean mining ministry, SMB, and CBG what role car companies and the aluminum industry more widely can play in strengthening respect for human rights in the mining sector. Guinea’s mining ministry said that it, “it remains open and ready to examine any initiative or measure of accompaniment adapted to a country’s context that could guarantee the evolution and improvement of practices in the mining sector.”[135] SMB said that, “industrial consumers of aluminum, and the autoindustry in particular, can play a determinative role in improving environmental and social standards in aluminum supply chains.”[136] CBG said “it believes in the advocacy, call to action, sourcing, certification, and auditing roles of the various stakeholders, including civil society, NGOs and bauxite production and processing companies, industrial aluminum consumers, and governments, to promote honest, transparent, and good faith discussions on environmental, social, and human rights issues in the bauxite development industry.”[137] As Guinea’s bauxite industry plays an increasingly central role in global supply chains, car companies, through engagement with their suppliers and the mining companies they source from, should work to ensure that Guinean communities benefit from, and are not harmed by, aluminum production.

Car Companies’ Responsible Sourcing Practices

Human Rights Due Diligence and the Car Industry

Under the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, companies have a responsibility to put in place human rights due diligence processes to identify, prevent, mitigate, and remedy human rights abuses throughout their supply chain.[138] Businesses whose operations or products are directly linked to adverse human rights impacts, including through their supply chains, should take appropriate action, including using their leverage to address the harms.[139] Companies must ensure respect for human rights in their operations even where a national government lacks the necessary regulatory framework or is unable or unwilling to protect human rights.[140]

Beyond the UN Guiding Principles, the majority of car companies examined in this report have made their own commitments to human rights due diligence. As part of the Drive Sustainability initiative, 11 major car manufacturers, including BMW, Daimler, Ford, Toyota, Volkswagen, and Volvo, in 2017 adopted the Global Automotive Sustainability Guiding Principles, which commit members to, “responsibly source raw materials used in their products.”[141] Guidance on implementing the principles states that companies, “are expected to conduct due diligence to understand the source of the raw materials used in their products” and that, “companies should work to reduce the risk of potential human rights violations in their operations and through their business relationships by identifying risks and remediating any non-conformance in a timely manner.”[142]

The extent to which car companies have operationalized their commitments to human rights due diligence varies by company. Overall, however, the car industry has significant work to do to integrate human rights due diligence effectively. In June 2020, a report by Investor Advocates for Social Justice, an NGO promoting responsible investing, examined in detail the human rights due diligence policies and practices of 23 companies in the automotive sector.[143] The report concluded that, “the automotive industry is failing to demonstrate respect for human rights,” that the sector’s “most severe human rights risks are in the supply chain,” and that there is “inadequate supply chain transparency or oversight to monitor even direct suppliers.”[144]

In preparing this report, Human Rights Watch and Inclusive Development International asked car companies about their overall approach to human rights due diligence as well as their specific approach to aluminum. Many of the car companies contacted said they have publicly available standards that require or encourage their direct suppliers to ensure respect for human rights and which, with varying degrees of rigor, require or encourage their suppliers to work with companies further up the supply chain to ensure respect for human rights.[145]

But while car companies’ public commitments to human rights standards are important, their enforcement and monitoring of those standards need significant strengthening. In its report on car companies’ human rights due diligence practices, Investor Advocates for Social Justice concluded that:

Enforceable commitments that are cascaded from one supplier to the next through the supply chain either do not exist or are not monitored…Few companies have robust management systems that enable them to embed human rights criteria into business functions like assessing suppliers before entering contracts, incorporating human rights into purchasing decisions, and monitoring compliance with human rights criteria in contracts.[146]

Prioritizing Minerals Critical for Electric Vehicles

Car company executives said that monitoring suppliers’ conduct, including their efforts to source responsibly, is an enormous challenge when car companies have thousands of direct suppliers, each with their own sometimes complex supply chains.[147]

Car companies have therefore often chosen to focus their supply chain due diligence efforts on certain priority raw materials. In some cases, the decision on what materials to prioritize is driven by regulatory requirements, such as the requirement under US and European Union law to conduct human rights due diligence on gold, tin, tungsten, and tantalum.[148] In other cases, car companies have conducted their own assessment of what to focus on, based on factors like the risk of human rights violations, reputational risk, the amount of material sourced by the company, and the leverage the company might have to change their suppliers’ conduct.[149]

This approach has led many car companies to prioritize certain minerals critical to electric vehicles, such as the cobalt needed for electric batteries.[150] Widespread reporting by human rights groups of child labor and other human rights abuses in cobalt mining communities in the Democratic Republic of Congo, which produced approximately 70 percent of world supply in 2019, has helped raise awareness of the human rights risk in the cobalt supply chain.[151] Eight of the nine car companies who responded to Human Rights Watch and Inclusive Development International said they have taken at least some steps to specifically address the risk of human rights abuses in their supply of cobalt.[152]

Car companies have also begun to prioritize human rights due diligence for other materials required for car batteries, such as lithium.[153]

For some companies, the decision to prioritize oversight of the supply chain for minerals linked to electric batteries is partly driven by the need for consistency between environmentally friendly vehicles and responsible sourcing. Ullrich Gereke, head of procurement strategy at the Volkswagen Group, said in November 2020 that, “For our e-mobility strategy, sustainable and responsible sourcing of raw materials is of the utmost importance.”[154] The Chairman of BMW Europe, Manfred Schoch, said in 2019 that, “The growth in electromobility is increasingly transforming the supply chain…When purchasing new materials, such as cobalt or lithium… the BMW Group [is] working intensely to ensure fair working conditions and respect human rights.”[155]

Aluminum is Currently a Blind Spot

Despite its central role in more fuel-efficient vehicles, the human rights impact of aluminum – and bauxite mining in particular – remains a blind spot for the car industry. Although car companies’ knowledge of aluminum supply chains varies, none of the nine companies that responded to Human Rights Watch and Inclusive Development International had, prior to being contacted for this report, mapped their aluminum supply chain to understand the particular human rights risks within it. When asked, for example, about connections between their operations and CBG and SMB, the two Guinean mining companies discussed above, car companies either refused to disclose information about their supply chains or said that they do not currently track their supply chains down to the mine level.[156] Only two companies, Volkswagen and Daimler, acknowledged in writing that they might have connections to one or both of the mines.[157]

The complexity of aluminum supply chains was a key reason cited by several car companies for their inability to identify the source of their aluminum products.[158] Volkswagen, for example, said in a June 2021 letter that, “due to the high variety and number of parts in our vehicles using aluminum, a process to track and trace all material back/up to mining level and have one hundred percent transparency for all aluminum parts is currently not possible.”[159] BMW said that, “due to the high complexity of the supply chain, full traceability down to mine or refinery level is currently not possible.”[160] Daimler said that, “through [exchanges] with our [aluminum] suppliers we realized many do not yet operate adequate traceability systems to make the connection to the mine site.”[161] BMW and Daimler said that confidentiality considerations with suppliers or between suppliers and sub-suppliers also prevented full traceability to the mine level.[162a] Ford did not say that confidentiality prevented full traceability. Rather, the company said that it “cannot disclose supply chain links to the mine level due to confidentiality obligations with suppliers.” [162b]

Several car companies acknowledged, however, the need for more efforts to understand aluminum supply chains and the human rights risks within them.[163] Volvo, for example, said in a December 2020 letter that, “We have made a prioritization of raw materials from a responsible sourcing perspective. Aluminum/Bauxite is one of the materials we have decided needs further investigation and evaluation of potential risks and impacts.”[164] At least one car manufacturer said that the complexity of aluminum supply chains should not necessarily be an obstacle to increased human rights due diligence, noting that even if car companies don’t have fully traceable supply chains in the short-term, they can still work with their suppliers to identify and address “hotspots” where there are significant risks of human rights abuses.[165]

Certification in the Aluminum Sector

Although the car industry as a whole has made limited efforts to source aluminum responsibly, several car companies, BMW, Daimler, and Audi, which leads Volkswagen Group’s aluminum sourcing activities, have joined the Aluminum Stewardship Initiative (ASI), an industry-led certification scheme that aims to, “recognize and collaboratively foster responsible production, sourcing, and stewardship of aluminum.”[166] Globally, an increased focus on responsible sourcing and human rights due diligence has contributed to the emergence of a range of certification schemes, like ASI, which are established by multistakeholder initiatives (MSI) or industry associations to audit mines and other facilities against an agreed standard.[167]

ASI, which was formed in 2015, has more than 150 members, including mining companies, refiners, industrial users of aluminum, and civil society groups.[168] ASI has developed a Performance Standard, which includes social, human rights and environmental factors, against which any actor in the aluminum supply chain – whether a mining operation, processing facility, or manufacturing plant – can seek certification.[169] Companies can join ASI provided that they commit to certify at least one of their facilities (a site or premises controlled by the company, not necessarily a mining site) against the Performance Standard within two years of joining, with certification requiring third-party audits of the facility’s compliance.[170] ASI has also developed a “Chain of Custody” standard that companies can use to demonstrate that an end-use aluminum product has been produced by mines, refineries, smelters and manufacturers that all respect ASI’s Performance Standard.[171]

ASI had by June 2021 certified 92 facilities against its Performance Standard in more than 40 countries.[172] In 2019, seven percent of global bauxite was mined by facilities certified against ASI’s Chain of Custody standard, as well as around four percent of global alumina and just over one percent of aluminum ingots. [173] ASI said that its preliminary analysis showed that 16 percent of bauxite produced globally in 2020 was certified against ASI’s Chain of Custody standard, which it said represented, “very strong year on year growth.”[174] ASI also said its data showed that globally 11 percent of operational bauxite mines, 11 percent of alumina refineries, and 20 percent of alumina smelters are currently ASI Performance Standard certified.[175]

Volkswagen, BMW, and Daimler told Human Rights Watch and Inclusive Development International that they were encouraging mines, refineries, and smelters to join ASI and expand the amount of certified aluminum produced worldwide.[176] Volkswagen, for example, said in a June 2021 letter that, “It is our goal to increase the share of certified materials in our portfolio…. We believe that the growing share of certified aluminum in the market including certified mining operations is the right way to institute more sustainable supply chains.”[177] Volkswagen said one of its brands is requiring ASI certification for certain aluminum components in its supply chain.[178] Daimler also said that it had made ASI a sourcing requirement for all future procurements for “all primary aluminum suppliers to our stamping plants and foundries in Europe” and that, “by sending a clear demand signal, we intend to support the mainstreaming of ASI in the market.”[179]

Certification processes can help car companies source responsibly by clarifying and defining industry standards and providing car manufactures with information about compliance with those standards at mines, refineries, and smelters in their supply chain. Participation in certification schemes is not, however, sufficient to discharge companies’ responsibilities to detect human rights abuses and provide remedies to victims of corporate abuses.[180] Third-party audits, a key element of certification, have been found to have severe limitations, including potential conflicts of interest, lack of human rights expertise among auditors, and inadequate consultation with affected communities.[181] Car companies’ efforts to source certified aluminum should only ever be one part of a broader due diligence process that includes supply chain mapping, risk analysis, mitigation measures, verification, grievance mechanisms, public reporting, and direct engagement with mines, refineries, and smelters implicated in, or at risk of, human rights abuses.

The different characteristics of certification schemes also means that they vary in their effectiveness in advancing human rights. In ASI’s case, despite its potential advantages, the initiative also has significant limitations. ASI’s board does not have equal participation and voting rights for impacted communities and civil society groups versus downstream and upstream industry representatives, even though it does allow for participation and input from non-industry players.[182] MSI Integrity, an NGO, found in a July 2020 report that where MSIs have minority representation of civil society groups or rights holder in their governing bodies, it exacerbates their tendency to avoid significant changes to their standards or oversight systems, particularly reforms that would strengthen human rights protections for communities and impose additional human rights obligations on companies.[183]

Fiona Solomon, ASI’s Chief Executive Officer (CEO), said in a July 2021 letter to Human Rights Watch and Inclusive Development International that ASI’s board is responsible for the corporate governance of the initiative, but emphasized that ASI’s Standards Committee, which includes equal representation from industry and civil society/community groups, is responsible for formulating the initiative’s standards and verification processes.[184] ASI’s board adopts standards once they have been formulated by the Standards Committee, although the board’s oversight is limited to assessing whether the committee followed due process and “review of material risks.”[185] ASI also has an Indigenous Peoples Advisory Forum (IPAF), made up of Indigenous, community, and civil society groups impacted by the aluminum sector, which functions as a “dialogue and engagement platform between ASI and representatives of Indigenous Peoples.”[186] ASI’s Standards Committee includes at least two members of IPAF.[187]

The Standard Committee is currently in the process of revising ASI’s standards, and Human Rights Watch and Inclusive Development International wrote to ASI’s Secretariat in April 2021 to provide comments on ASI’s proposed revisions.[188] Key issues raised in the letter included the need for increased protections for communities that lose land to mining, particularly those with customary land rights, and a need for the standards to more clearly articulate communities’ right to participate in, and benefit from, natural resource exploitation.[189] The letter praised ASI’s decision to integrate a supply chain due diligence requirement into the standard, in line with the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas,[190] but also underscored that ASI standards should require companies to conduct due diligence for the full range of human rights abuses in their supply chains, whether they occur in conflict-affected and high-risk areas or otherwise.[191] ASI’s revised standards do include strengthened language on managing greenhouse gas emissions at aluminum smelters, including requiring members to reduce the volume of emissions per metric ton of aluminum manufactured and a requirement to set absolute emissions reduction targets in line with the most ambitious goal of the Paris Agreement on climate change to keep global warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius.[192]

More broadly, however, the human rights requirements in ASI’s Performance Standard currently lack adequate detail and do not break down key human rights issues into specific criteria against which companies’ policies and practices can be assessed. The section of ASI’s revised Performance Standard on resettling communities, for example, requires companies to develop a Resettlement Action Plan for physical displacements, in line with relevant IFC standards, and requires that a company regularly review the plan and implement improvements to ensures that communities’ “living conditions and income generating options equal or exceed those prior to the resettlement.”[193] The IFC’s resettlement standards are extremely lengthy, and resettlements themselves are very complex. ASI’s Performance Standard does not break down the IFC standard into specific criteria against which auditors should assess a Resettlement Action Plan or evaluate companies’ efforts to ensure communities’ living conditions are maintained or improved.[194]

The lack of detail in ASI’s Performance Standard can be contrasted with the more specific requirements in a standard developed by the Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance (IRMA), a mining sector certification scheme whose members include BMW, Ford, and Daimler. IRMA’s standard focuses only on mining companies’ operations, not facilities further down the supply chain, although IRMA is developing a processing standard that would apply to smelters and refineries.[195] IRMA’s standard, which so far has not been adopted by any bauxite mine but has been by mines in other mineral sectors, breaks down each of its key elements into detailed criteria against which mines should be assessed.[196] IRMA’s section on resettlement, for example, although not yet finalized, includes 28 criteria with which to asses a mine’s resettlement policies and practices, ranging from community engagement during resettlement to monitoring and evaluating the impacts of resettlement on households after it is complete.[197] Human Rights Watch is a member of IRMA’s board.

In addition to the lack of detail in its Performance Standard, ASI’s current certification process contains insufficient guarantees that the third-party audits necessary for certification effectively capture whether companies respect the rights of local communities. There are, for example, insufficiently detailed requirements in ASI’s assurance standard setting out when and how auditors should consult with local communities and the issues on which auditors should seek communities’ input.[198] The guidance to IRMA’s mining standard, in contrast, sets out detailed “means of verification” that describe when and on what issue auditors should consult with impacted communities or civil society groups.[199] ASI’s assurance manual also lacks adequate guidance on how outreach to affected communities should be conducted so that they can freely and openly engage in the process, how much consultation with affected communities is required, and how their experiences and perspectives are to be reflected in auditing reports.[200] Solomon, ASI’s CEO, said in a July 2021 letter to Human Rights Watch, that, “enhancing guidance for auditors on consultation with, and outreach to, affected communities is being addressed as part of the current Standards Revision and through development of new auditor training modules for 2022.”[201]

ASI currently publishes a summary of the audit conducted for each certification, but the summaries do not include adequate detail to enable external stakeholders, including local community and civil society groups, to investigate the quality of the audit and ensure a company addresses the deficiencies it identifies. The lack of detail in summary audits reports is in part a result of the lack of detailed criteria for assessment in ASI’s Performance Standard. But the summary audits also provide little information about why a company is or is not in conformity with the criteria in the Performance Standard, often limiting their analysis to a few short sentences.[202] Solomon, ASI’s CEO, said that, “auditors prepare the summary statements and are expected to give the reader a clear sense of how they came to the conclusion of conformance or non-conformance (major or minor).”[203] In contrast to ASI, the two summary audit reports published by IRMA so far provide clear explanations as to why a company met or partially met the standard’s detailed criteria.[204] IRMA’s summary audits reports, however, do not include any explanatory narrative where a company is deemed not to meet a specific IRMA criterion.

ASI does have a grievance mechanism that can be accessed by communities that allege that a member company or a certified facility is implicated in human rights abuses.[205] ASI’s assurance and complaints processes create pathways for a member company implicated in serious human rights abuses to be expelled from the initiative but does not require it.[206] Solomon, ASI’s CEO, said that if a member company was implicated in serious human rights abuses, “a time-bound corrective action (remedial action) plan would be required…and other consequences (loss of membership and/or certification) may also apply.”[207]

The Future of Certification in Aluminum Supply Chains