Almost 12 years ago, on December 2, 2010 – the football world was surprised, some even shocked, that Qatar had won the right to host the FIFA Men’s World Cup 2022. The Gulf peninsula state, with a population of just over a million, had only three stadiums and little other infrastructure and summer temperatures of up to 50 degrees Celsius.

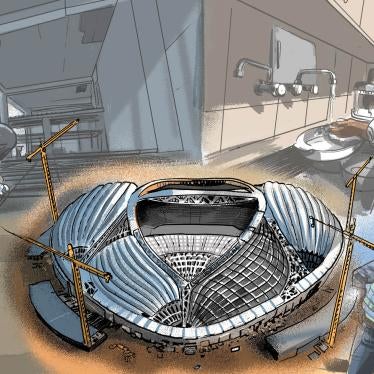

There was concern about the feasibility of delivering the World Cup in Qatar’s desert temperatures for both fans and footballers, who are not allowed, by FIFA’s rules, to play in more than 32 degrees Celsius (89.6 degrees Fahrenheit) without mandatory cooling breaks. But Qatar batted away these concerns with their plans to build solar-powered air cooling stadiums, and necessary infrastructures like a metro, a new airport, and a substantial number of hotels.

Little to no attention was given by the sporting and state authorities, however, to the conditions for the millions of migrant workers who would be needed to build the massive infrastructure and stadiums for the World Cup in the extreme heat. In 2010, low-paid migrants from Asia and Africa already made up more than 90 percent of the country’s workforce. Football’s governing body, FIFA, in its 2010 evaluation of Qatar’s bid acknowledged the “significant human resources” required for the considerable number of infrastructure projects, but otherwise did not require labor rights commitments from Qatar, despite human rights reports detailing abuses against migrant workers there.

Winning the bid did not have to spell disaster. Qatari authorities could have made the necessary reforms to ensure that workers had decent living and working conditions. A 2012 Human Rights Watch report identified Qatar’s systemic gaps in labor protection as well as its abusive kafala (sponsorship) system that ties workers’ legal status to their employer. The kafala system enables serious abuses including forced labor, such as charging recruitment fees that trap workers in debt, confiscating their passports, stealing their wages, and providing unsafe working conditions and crowded and unsanitary labor camps. Several human rights organizations and trade unions issued similar warnings and recommendations.

The past decade has been a tug-of-war to secure reforms to safeguard workers and end the kafala system. Under pressure from the International Labour Organization (ILO), Qatar introduced key labor protections including, in 2020, a minimum wage, an end to a requirement for exit permits from employers for migrants to leave the country, and allowing migrant workers to change jobs before the end of their contracts without first obtaining their employer’s consent. They also operationalized the Workers’ Support and Insurance Fund to pay workers back wages when companies defaulted.

These reforms are crucial. Many workers were able to send money to their families to feed them, pay school fees for their children, and build new homes. But many workers did not feel the impact of these reforms because they were introduced too late or were poorly enforced. And reforms such as the 2014 worker welfare standards and the 2017 Universal Reimbursement Scheme which reimbursed workers charged illegal recruitment fees applied only to people contracted to work on projects for the Supreme Committee for Delivery and Legacy, the government’s World Cup agency.

Neither Qatar nor FIFA had spared much thought for the migrants needed for the World Cup, but after 12 years of hard work, Qatar is about to deliver the games. It has not been an easy road with a three and half year-forced isolation by its neighbors and the Covid-19 pandemic, but the Qatar World Cup’s lasting legacy will be whether they can lock in and build on these reforms to stem worker abuses. The most crucial test is whether Qatar and FIFA will provide a remedy for the deaths and other abuse since 2010. FIFA and Qatar should not forget migrant workers who returned home humiliated without their wages, injured or dead, with families left uncompensated and in debt.

In July, a worker who had left Qatar with seven months’ unpaid wages told us: “When surviving in Qatar became unaffordable despite charity support for food, we decided to return. I was gutted on the flight back. Homecoming is usually a happy occasion when we bring back gifts for families. I was instead returning empty-handed without any savings on a ticket purchased by my family with borrowed money.” After over a year and a half of waiting, he finally got the overdue check via the Qatari embassy.

“It was like a dream,” he said. “With the compensation, I managed to get out of the debt trap my family had been stuck in for years.”

Deaths and harm cannot be undone, but for so many migrant workers and families waiting for compensation, some financial assistance—a slender slice of the huge profits from the event—could have far-reaching consequences. A large-scale attempt to give back to those migrant workers short-changed while making the World Cup possible would send a powerful, positive message from FIFA and Qatari authorities.

It is not too late to commit to a remedy fund and to end this long, tumultuous journey on a positive note that finally puts migrant workers at the center of the World Cup they made possible.