Ms. Tania Reneaum Panszi

Executive Secretary

Inter-American Commission on Human Rights

Organization of American States

1889 F St NW

Washington, D.C., 20006

Re: Request for Hearing on Voter Suppression Against Black, Latinx, and Native American People in the United States of America

Dear Secretary Panszi:

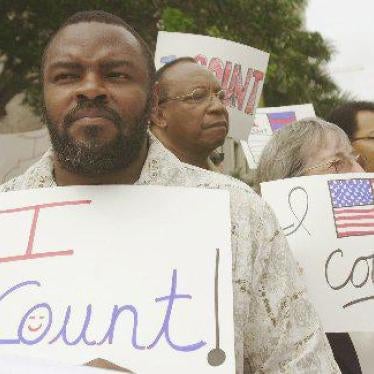

Pursuant to Articles 61, 62 and 66 of the Regulations of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, the undersigned organizations respectfully request a hearing during the 184th Period of Sessions (June 21-24, 2022) to address the issue of the suppression and dilution of voting by Black, Latinx, and Native American people in the United States of America.

BASIS FOR THE HEARING

Article 23(1) of the American Convention on Human Rights provides that every citizen has the right to participate in the conduct of public affairs, including by voting with “universal and equal suffrage and by secret ballot that guarantees the free expression of the will of the voters.” People of color in the United States, and in particular Black, Latinx, and Native American residents, have faced and continue to face barriers to participation in representative democracy on an equal basis with their white counterparts. Barriers to the right to vote are now rapidly increasing and threaten to irreparably undermine US democracy. Following his recent visit to the United States, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on minority issues found that “effective protection of this fundamental human right is weak in the United States.”[1]

Laws Restricting Access to Voting.

While the US constitution has many provisions related to the right to vote, and Congress passed the Voting Rights Act in 1965 expressly to prohibit discrimination against Black citizens in voting, states have been steadily weakening the meaning and enjoyment of those protections for Black and Brown citizens for more than a decade. Since the 2013 US Supreme Court decision in Shelby County, Alabama v. Holder, which gutted a key provision of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 requiring jurisdictions with a history of racial voting discrimination to obtain federal clearance before changing their voting laws, states have implemented dozens of new laws restricting and impeding voting access.

The pace of the adoption of such laws accelerated over the last two years following the 2020 election,[2] with at least 36 new voting restrictions being passed through 14 state legislatures since the beginning of 2022.[3] In addition to passing voter restrictions intended to suppress voters of color, state legislatures are also passing laws that undermine election processes and allow for election subversion in direct response to the events of the January 6th, 2021 insurrection at the US Capitol. Although the Shelby County decision left room for Congress to restore the preclearance requirement, which would have prevented many of these laws from going into effect, Congress has failed to act in the nearly ten years since that decision. Earlier this year, bills[4] that would have restored federal oversight in locations with a history of racial discrimination in voting, expanded opportunities to exercise the right to vote, provided protections from voter suppression, and enhanced election security were blocked from even receiving a vote in the US Senate.[5]

The imposition of new obstacles to voting access continues almost daily. Laws adopted in recent months make it more difficult to register to vote or to receive an absentee or mail-in ballot, restrict voting times or locations, and even ban and criminalize providing food or water to people waiting in long lines to vote. Typical of these state voter suppression laws is Florida’s Senate Bill 90.[6] Like recently passed laws in other states, the Florida law contains numerous provisions designed to make voting more difficult and less likely – including:

(a) a requirement that groups working to register voters inform people that they might not turn the registrations into the state on time, or at all, which is likely to discourage prospective voters from proceeding to complete the application;

(b) banning “any activity with the intent to influence or effect of influencing a voter” within 150 feet of a polling station, which will prevent groups from engaging in bipartisan voter assistance such as the provision of food and water to voters waiting in long lines at polling stations;

(c) limitations on the availability of ballot drop boxes;

(d) onerous new identification requirements for absentee ballots;

(e) several measures that make voting by mail harder.

Restrictions on voting methods such as early and mail-in voting are direct attacks on voting access for people of color. Record turnout by Black and Latinx voters in 2020 was supported by their greater likelihood to use early and mail-in voting methods,[7] which are now being restricted in many states. Black voters used early in-person voting at a higher rate than did white voters,[8] while Latinx voters made more use of voting by mail.[9] These new restrictions followed others adopted in Florida over the years, including such measures as prohibiting early voting on the Sunday before an election – widely understood to be relied on by Black voters as Black churches provide transportation to the polls after Sunday services in an effort known as “Souls to the Polls.” SB 90 also creates an election crime office – an “election police force” – specifically to investigate and prosecute allegations of election law violations and fraud, even though cases of election fraud are extremely rare.[10] Among the election-related activities that have been criminalized is so-called “ballot harvesting,” which will prevent volunteers from churches and community groups from collecting ballots from voters and delivering them to election offices or placing them in drop boxes.[11] This is a process that has been heavily relied upon in Black communities, and especially by voters whose age or physical disability makes it difficult for them to deliver their own ballots.[12] These threats of criminalization serve no legitimate purpose but are intended to and do intimidate voters and suppress their willingness to exercise their right to vote.

On 31 March 2022, a federal district court in Florida issued a sweeping injunction prohibiting Florida from implementing many of the new measures contained in SB 90,[13] finding that they had been adopted “with the intent to discriminate against Black voters.”[14] The court found the violations so egregious that it placed Florida under federal preclearance requirements for the next ten years and prohibited it from passing any law relating to drop boxes, line warming activities, or third party voter registration organizations without getting the court’s permission.[15] In so doing, the district court recognized that “the right to vote, and the VRA particularly, are under siege” in the nation’s courts as well as in its state legislatures. The district court cited a string of other recent decisions,[16] including from the US Supreme Court, that threaten to completely eviscerate protections for voting rights and demonstrate that the Florida court’s decision may well be overturned on appeal, leaving Florida voters at the mercy of myriad new obstacles and intimidation.

The day before the federal district court in Florida struck down SB 90, the Governor of Arizona signed HB 2492 into law, a bill requiring all voters to provide documentary proof of citizenship in order to vote in presidential elections. Arizona passed this law despite the fact that the US Supreme Court held in 2013 that requiring voters who only vote in federal elections to provide documentary proof of citizenship is unconstitutional.[17] The bill also requires voters to provide proof of their address, which is especially difficult for Native American voters who live on reservations and do not have traditional mailing addresses. This bill is expected to and may well have been intended to have devastating effects on Latinx and Native American voters in Arizona. Arizona’s insistence on passing a bill that directly violates US Supreme Court precedent from as recent as 2013 is representative of many state governments’ belief that the current Court is increasingly hostile to the voting rights of Black, Latinx, and Native American voters and less willing to protect them from discrimination.

New threats also increasingly come from far-right activists gaining or seeking to gain control of state and local election authorities.[18] At least 15 candidates who have questioned or denied the legitimacy of President Biden’s election are now running for the office that oversees elections in the states in which they live.[19] In Georgia, a new law abolished existing county election boards and handed control over to newly appointed commissions. One Georgia county’s new elections board attempted to close seven polling places and require all of the voters living there to drive 15 miles or more in order to vote at a single polling place– and no public transportation exists in the area.[20] County election boards across Georgia closed 214 polling places between 2012 and 2018.[21]

In states with large Latinx populations, many new voting restrictions are aimed at suppressing their growing impact on elections. In Florida, Arizona, and Texas, new laws make it difficult or impossible for voting rights organizations to provide assistance in casting ballots. In Texas, monthly citizenship checks have frequently purged eligible voters from rolls in error.[22] Another provision of Texas law adding multiple layers of identification requirements for mail-in ballots has resulted in tens of thousands of ballots being rejected.[23] The ballots of Black voters appear to have been rejected at a disproportionate rate.[24] Bans on 24-hour and drive through voting, which were used more heavily by people of color, are anticipated to suppress the Latinx vote.[25]

Redistricting.

The US is in the midst of a redistricting cycle that is consolidating power in one overwhelmingly white political party in southern states, where a significant majority of people of color live. Redistricting has been one of the most effective and consistent tactics used to disenfranchise voters of color in the South. The current cycle is being manipulated to dilute the voting power of Black and other racial minority groups, despite the fact that they represent a majority of US population growth since the last redistricting cycle. As of December 2021, 26 lawsuits had been filed in seven US states challenging new district maps as either racially discriminatory or as partisan gerrymandering, which often has a racially disparate impact even if not intentionally based on racial motivations.

In Alabama, Black voters are challenging new district maps that employ both “packing” and “cracking” to dilute the Black vote – many Black voters are packed into a single district, and the remainder cracked among multiple districts to prevent their votes from swaying elections in all but a single district. In a detailed and forceful opinion,[26] a three-judge panel held that the plaintiffs were substantially likely to win on their claims that the new district maps were racially discriminatory and ordered Alabama to draw new maps that would correct this inequity, but the US Supreme Court put that order on hold,[27] and the discriminatory district maps will be in place for this year’s election cycle. Although the population of Alabama is 27% Black, Black voters are a majority in only one of the state’s seven districts or just 14% of the districts.[28] Though the three-judge panel ordered Alabama to draw maps that created two Black opportunity districts to ensure the state’s Black voters had equal representation, the US Supreme Court put that decision on hold and may very well overturn it completely in the near future.

In Texas, Black, Latinx and Asian voters, along with civil rights organizations and the Department of Justice, are challenging cracking and packing that resulted in increased white voting power despite most of the population growth being non-white. According to the Brennan Center, white people are the majority of eligible voters in 60% of the newly drawn districts despite accounting for less than 40% of population growth, and two new Congressional seats Texas gained after the recent census were gerrymandered to give them white majority districts, despite the fact that the percentage of white voters in Texas decreased.[29] Half of the population growth in Texas (and nationwide) was Latinx.[30]

The US Supreme Court asserted that it was halting the three-judge court’s decision that would have increased Black voting power in Alabama because it was too close to the election, invoking an overbroad and inconsistently applied rule known as the Purcell principle. Yet over two months later, even closer to the election, the US Supreme Court refused to apply that principle in a Wisconsin redistricting case. There, the US Supreme Court ordered the Wisconsin state supreme court to redraw Wisconsin’s state legislative districts after the state court originally drew them to increase the number of majority Black state legislative districts from six to seven.[31]

As the US Supreme Court has refused to block state laws suppressing Black, Latinx, and Native American voters’ right to vote, it has also increasingly prevented Black, Latinx, and Native American from electing the representatives of their choice by allowing racially discriminatory redistricting plans to go into effect and preventing states from implementing redistricting plans that increase minority representation. While the federal judiciary is actively rolling the clock back on voting rights for Black, Latinx, and Native American voters, the US Congress is failing to pass legislation to remedy the problems created by recently passed state laws and federal court decisions. America’s system of checks and balances is quintessential to its democratic form of government, yet that system is failing to protect America’s Black, Brown, and Indigenous communities.

The Spread of Disinformation.

Disinformation spread using digital platforms has developed into a major threat to democracy in the US. Throughout the 2020 election cycle, disinformation was used to threaten and intimidate voters, as well as to mislead them in order to suppress turnout. Voters received robocalls, traced to far-right operatives, spreading lies about dangers associated with mail-in voting – particularly critical during an election impacted by a pandemic. Threatening emails were sent to Florida voters. They appeared to be from a far-right US hate group but were later discovered to have originated in Iran. False information about voter fraud, including fake news stories and doctored videos, was widely spread on social media, engendering distrust in the election process and suppressing voter turnout.[32]

Disenfranchisement of Voters with Felony Convictions.

In many US states, people convicted of any of a long list of felony offenses are automatically deprived of their right to vote, with no consideration of their individual circumstances. In some states, this disenfranchisement continues to apply long after people have served their sentences of incarceration.[33] As the United Nations Human Rights Committee has observed, the right to vote “lies at the heart of democratic government based on the consent of the people,” and any restrictions on that right must be “objective and reasonable,” and not based on discrimination.[34]

Although the Convention permits a State party to regulate voting on the basis of several specified factors, including “or sentencing by a competent court in criminal proceedings,” the imposition of felon disenfranchisement laws in the US is plainly discriminatory in purpose and effect. Data estimates compiled by The Sentencing Project as of 2020[35] illustrate the racially disparate impact of these disenfranchisement laws, which tend to have the most disproportionate impact in southern states:

Total Disenfranchised Due to Felony Convictions

|

State |

Total Disenfranchised |

Voting Age Population |

Percent Disenfranchised |

|

Alabama |

328,198 |

3,671,110 |

8.94% |

|

Florida |

1,132,493 |

14,724,113 |

7.69% |

|

Georgia |

275,089 |

7,254,693 |

3.79% |

|

Louisiana |

76,924 |

3,452,767 |

2.23 |

|

Mississippi |

235,152 |

2,228,659 |

10.55% |

|

Tennessee |

451,227 |

4,964,909 |

9.09% |

|

Texas |

500,474 |

17,859,496 |

2.80% |

Black Voting Age Population Disenfranchised Due to Felony Convictions

|

State |

Total Disenfranchised |

Voting Age Population |

Percent Disenfranchised |

|

Alabama |

149,716 |

962,519 |

15.55% |

|

Florida |

338,433 |

2,194,488 |

15.42% |

|

Georgia |

145,601 |

2,322,275 |

6.27% |

|

Louisiana |

47,951 |

1,087,270 |

4.41% |

|

Mississippi |

130,501 |

817,493 |

15.96% |

|

Tennessee |

174,997 |

814,576 |

21.48% |

|

Texas |

138,926 |

2,372,001 |

5.86% |

Such disparities are potentially outcome determinative in elections. For example, in the 2018 election for governor in Georgia, white Republican Brian Kemp defeated Black Democrat Stacey Abrams by a margin of only about 1.4%.[36] In the 2020 Presidential election, official counts showed former-President Trump won Florida by about 3%; President Biden won Georgia by only 0.23%.[37]

Moreover, many US jurisdictions extend the denial of voting rights for persons convicted of felony offenses long past the sentences imposed by a court – sometimes effectively for life. More than five million Americans who are no longer incarcerated are nevertheless denied the right to vote due to a criminal conviction, and almost half of that population resides in the South. The scope of their disenfranchisement varies depending on the laws passed by the US state in which they reside.

Even where bars based on felony conviction have been eased, right-wing politicians continue to find ways to prevent people from voting. For example, voters in Florida approved a law to automatically restore voting rights to about 1.4 million disenfranchised voters in 2018. In 2019, the Florida legislature passed a new law prohibiting the newly re-enfranchised (disproportionately people of color) from voting until they paid all court-related debt,[38] which can amount to many thousands of dollars and act effectively as a lifetime bar. In a lawsuit challenging the Florida law, plaintiffs (including two Black women represented by SPLC) argued the law was an unconstitutional poll tax. Although a district court struck down the law as unconstitutional after several days of trial, a federal appeals court first stayed and then overturned that ruling and reinstated the law.[39] The US Supreme Court refused to step in to overturn the appeals court’s stay.[40]

Criminal prosecution of people who make honest errors will further suppress efforts to regain the right to vote. In Tennessee, a Black woman named Pamela Moses was recently sentenced to six years in prison after being convicted of breaking the law by registering to vote, even though she relied upon advice provided by local election officials in doing so.[41] Another Black woman named Crystal Mason was sentenced to five years in prison by a Texas court after casting a provisional ballot while under the mistaken belief that she was entitled to vote. Her ballot was never counted.[42]

PURPOSE OF THE HEARING

The US presents itself to the region, and to the world, as the leading defender of democracy. The Biden administration recently hosted the first session of a two-part, global Summit for Democracy, and will soon host the Summit of the Americas, focused in part on protecting and promoting strong and inclusive democracies in the region. The US often uses its influence to apply pressure for greater transparency, accountability, and legitimacy to elections and political systems in the Americas. But the US is currently failing to protect its own people from clear and present dangers to their rights to live in and equally participate in a democratic society within its own borders. As discussed above, this is due to action and inaction by various parties. Nevertheless, the decline of US democracy is a threat to democracy and international human rights throughout the region and globally. We therefore believe it is vital for the Commission to address the undermining of US democracy and its government’s failures to take necessary actions to protect and strengthen its democracy.

If granted, the requested hearing would take place five months before the next US election cycle, when control of the US House and Senate, as well as many vital state and local offices nationwide, will be decided. The hearing would provide an opportunity for marginalized voting populations and their civil society representatives to present evidence that would provide the Commission with up-to-date information and an opportunity to make appropriate findings and consider what actions it can take to defend a rapidly diminishing democracy. Applicants will present evidence showing the ways in which the votes of people of color in the US are being suppressed and diluted and will offer concrete recommendations for how the Commission can act in support of strengthening democracy in the US and throughout the region. The hearing will also provide an opportunity for federal, state, and local representatives with the authority to implement human rights obligations to address the Commission and those impacted by these issues.

The undersigned organizations respectfully request a hearing on “Voter Suppression Against Black, Latinx, and Native American People in the United States of America” for the 184th Period of Sessions, which will take place June 13-24, 2022.

Sincerely,

Southern Poverty Law Center

American Civil Liberties Union

Human Rights Watch

Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights

League of Women Voters of the United States

Oxfam America

[1] Report of the Special Rapporteur on minority issues, Fernand de Varennes, on his visit to the United States of America, 14 March 2022, at 6.

[2] Voting Laws Roundup: February 2022, Brennan Center for Justice, 12 January 2022.

[3] The race to change voting rules is on, CNN, 22 March 2022.

[5] After a day of debate, the voting rights bill in blocked in the Senate, New York Times, 19 January 2022.

[6] SB 90: Elections, Florida Senate.

[7] What Methods Did People Use to Vote in the 2020 Election?, US Census Bureau, 29 April 2021.

[8] Black voters most likely to say November election was run very well, Pew Research Center,, 12 January 2021.

[9] Voting trends analysis prepared for SPLC, 2 November 2020.

[10] Florida Senate Passes Voting Bill to Create Election Crimes Agency, New York Times, 4 March 2022.

[11] Florida lawmakers approve an elections police force, the first of its kind in the U.S., Washington Post, March 9, 2022.

[12] Voters with Disabilities Face New Ballot Restrictions Ahead of Midterms, Pew Stateline, 12 April 2022.

[13] Final Order Following Bench Trial, League of Women Voters v. Lee, United States District Court for the Northern District of Florida, 31 March 2022.

[14] Final Order, passim.

[15] The court invoked a lesser known preclearance provision of the VRA – section 3(c) – known as “bail in.”

[16] Id. at 3.

[17] Arizona v. Inter Tribal Council of Arizona, 570 U.S. 1 (2013).

[18] ‘Slow-motion insurrection’: How GOP seizes election power, Associated Press, 30 December 2021.

[19] Here’s where election-denying candidates are running to control voting, NPR, 4 January 2022.

[20] Poll closure plan defeated in rural Georgia’s Lincoln County, Atlanta Journal-Constitution, 30 December 2021.

[21] Id.

[22] Texas’ renewed voter citizenship review is still flagging citizens as “possible non-US citizens,” Texas Tribune, 17 December 2021.

[23] Almost 25% of mail-in ballots were rejected in Texas for its March 1 primary election, NPR, 6 April 2022.

[24] Mail Ballot Rejections Surge in Texas, With Signs of a Racial Gap, New York Times, 18 March 2022.

[25] Latino Communities on the Front Lines of Voter Suppression, Brennan Center, 14 January 2022.

[26] Milligan v. Merrill, United States District Court for the Northern District of Alabama, 24 January 2022.

[27] Merrill v. Milligan, 595 U.S. ___ (2022).

[28] Alabama Redistricting Ruling Sparks Hope for Democrats, New York Times, 25 January 2022.

[29] Redistricting Litigation Roundup, Brennan Center for Justice, 20 December 2021.

[30] It’s Time to Stop Gerrymandering Latinos Out of Political Power, Brennan Center, 4 November 2021; Black and Latino voters have been shortchanged in redistricting, advocates and some judges say, Washington Post, 25 January 2022.

[31] Wisconsin Legislature v. Wisconsin Elections Commission, 595 U.S. ______ 23 March 2022

[32] Overcoming The Unprecedented: Southern Voters’ Battle Against Voter Suppression, Intimidation, and a Virus, Southern Poverty Law Center, 10 March 2021.

[33] Felony Disenfranchisement Map, ACLU, 2022.

[34] General Comment Adopted by the Human Rights Committee under Article 40, Paragraph 4, of the ICCPR, CCPR/C/21/Rev.1/Add.7, August 27, 1996, Annex V (1).

[35] Locked Out 2020: Estimates of People Denied Voting Rights Due to a Felony Conviction, The Sentencing Project, 30 October 2020.

[36] Georgia Governor Election Results, The New York Times, 28 January 2019.

[37] Presidential Election Results: Biden Wins (interactive map), The New York Times.

[38] Voting Rights Restoration Efforts in Florida, Brennan Center for Justice, 11 September 2020.

[39] Jones v. Governor of Florida, 975 F.3d 1016 (11th Cir. 2020).

[40] Supreme Court Deals Major Blow To Felons' Right To Vote In Florida, NPR, 17 July 2020

[41] Black Woman’s Bid to Regain Voting Rights Ends with a 6-year prison sentence, New York Times, 7 February 2022.

[42] Texas Court of Criminal appeals will review Crystal Mason’s controversial illegal-voting conviction, Texas Tribune, 31 March 2021.