The 16-year-old Venezuelan boy hugged his dog as he sat by the side of the road. They were in Colombia’s Berlin Paramo, the highest point on the route used by Venezuelans walking across the Venezuela-Colombia border, where temperatures can drop to 0°C. The boy and two other teens had been walking for hours.

Perhaps even harder than listening to their stories was the feeling of déjà vu and the certainty that their suffering was unnecessary.

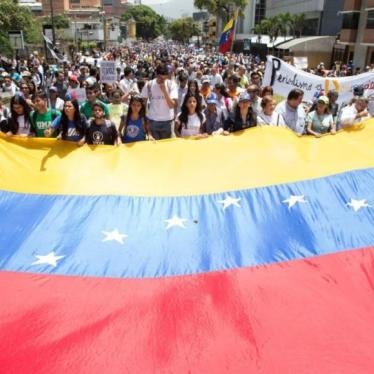

In 2018, we saw some of the first hundreds of Venezuelans, including pregnant women and children, walking for days toward larger cities in Colombia and other Latin American countries. They were escaping the devastating human rights, humanitarian, and political crisis in Venezuela that has forced over 6 million people to leave.

Three years (and a pandemic) later, hundreds are still taking these dangerous roads, ill-prepared for the extreme temperatures and security risks. UN agencies estimate that 400 people walk these roads every day to reach Bogotá and other Colombian cities, including 10 to 15 unaccompanied or separated children, who are exposed to human trafficking and, in parts of the road, to recruitment by armed groups.

The Maduro government’s brutal crackdown on opponents in Venezuela has led to the first formal investigation of alleged crimes against humanity in the Americas by the International Criminal Court prosecutor. Meanwhile, the humanitarian emergency in the country, which predates the Covid-19 pandemic, has left one in three Venezuelans without enough food and millions in need of proper health care.

The Colombian government has taken landmark steps to provide legal status to the over 1.8 million Venezuelans in the country. This critically important step ensures that Venezuelans can legally work in Colombia, making them safer from exploitation. Once they obtain their permits, they can send their children to school, seek healthcare, and report crimes without fear of being deported.

The Colombian government and UN and international humanitarian agencies have created several centers along the road to provide walkers with food, short-term shelter, health care, and access to the internet. In 2021, over 100,000 walkers received help. Colombian groups, some with the support of organizations such as Aid for Aids and Funvecuc, have also set up their own stations along the road.

But, with very limited exceptions, including for families with children under 12 and pregnant women, no one provides Venezuelan walkers with transportation. It may sound absurd, but most walkers aren’t allowed on buses.

The answer appears to be a combination of fear, poor laws, and cruel policy. Some transportation companies are concerned that allowing migrants without legal status on their buses could amount to “trafficking of migrants,” a crime under Colombian law. An immigration decree passed in 2018 makes it an administrative infraction for companies to carry migrants without legal status, so some transportation companies fear they could be fined since most Venezuelans who cross the border on foot have not yet been able to regularize their status. And some mayors of cities where they are heading want to slow down the influx of Venezuelans, government officials and humanitarian workers told us. Some appear to believe that allowing Venezuelans to use buses will persuade more to leave their country.

But thousands of Venezuelans, like many desperate migrants in the region, have not been dissuaded by this policy. They just suffer more because they have to walk.

The Colombian government should work with humanitarian agencies to provide transportation for the walkers and revise laws so that Venezuelans can move around the country safely.

Helping Venezuelan exiles get to their final destination by bus wouldn’t just be humane. It also makes economic sense. UN agencies and their partners spend approximately $200-$300 daily to feed and support each walker. A $30 bus ticket would leave more funding to help Venezuelans where they choose to live or ensure they have quicker access to legal status.

In 2020, when Covid-19 hit Colombia, many Venezuelans lost their jobs and tens of thousands decided to return home. Colombia provided buses then to take them back to the border, so there is no logistical reason they couldn’t offer bus service now.

The walkers we saw in 2021 receiving humanitarian aid during their difficult journey were better off than those we saw in 2018 and had no assistance. No one wins by making them suffer needlessly. Colombia has made the right decision to give Venezuelans legal status, but now it must take this critical step to end the suffering along the road.