With the conclusion this summer of both UEFA Euro 2020 and CONMEBOL Copa America, qualifying matches for the FIFA World Cup, to be held in Qatar during November-December 2022, are set to resume next month. To a greater extent than previous tournaments, the Qatar World Cup has been mired in controversy. In addition to extensive reports of intrigue and corruption that generally accompany the selection of the host nation, the rights and treatment of migrant construction workers have also figured prominently. Mouin Rabbani, Editor of Quick Thoughts and Jadaliyya Co-Editor, interviewed Hiba Zayadin, Gulf researcher at Human Rights Watch, to get a better understanding of the issues involved.

Mouin Rabbani (MR): Who are the laborers involved in the construction of facilities for the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar? Do we have reliable data about their numbers, countries of origin, average pay, length of stay, and legal status in Qatar, and about worker deaths and injuries?

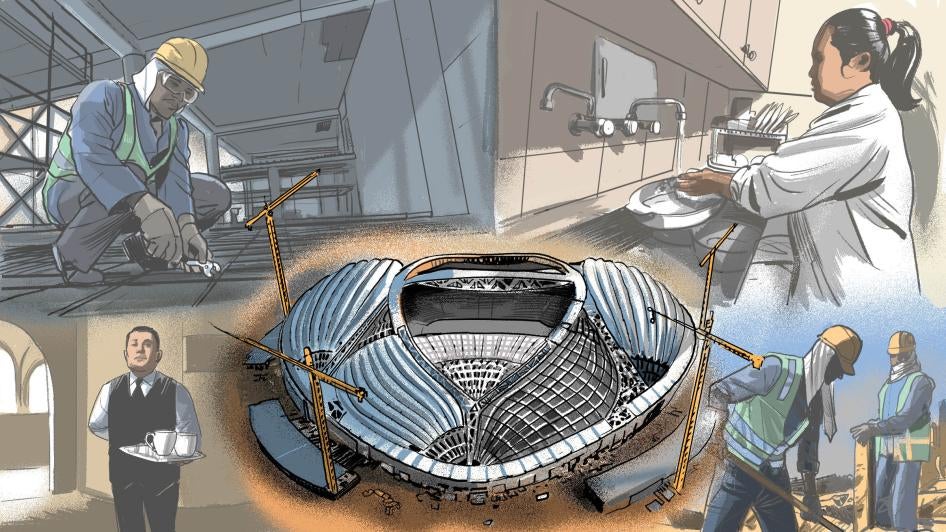

Hiba Zayadin (HZ): Qatar relies almost entirely on about two million migrants, who make up ninety-five percent of the country’s workforce in sectors ranging from construction to services to domestic work. Qatar’s migrant workers come predominantly from India, Nepal, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Kenya, and the Philippines.

They come to Qatar because they lack stable job opportunities in their home countries, or because they believe they can earn more money working abroad. Many leave behind families who depend on them financially. Qatar has the highest ratio of migrants to citizens in the world. Without these workers, its economy would grind to a halt.

Unfortunately, Qatar’s census data does not disaggregate the population by national origin, nor does Qatar publish regular, independently verifiable statistics on average pay, length of stay, or legal status in the country. In September 2020, Qatar passed legislation establishing a basic minimum wage of 1,000 QAR (US$274) that applies to all workers, regardless of nationality or employment sector.

For the past four years, Human Rights Watch has repeatedly urged the Qatari authorities to investigate the causes of unexpected or unexplained deaths among often young and otherwise healthy migrant workers, and to regularly make such data—broken down by age, gender, occupation, and cause of death—publicly available. Human Rights Watch has also urged Qatar to adopt and enforce adequate restrictions on outdoor work to protect workers from potentially fatal heat-related risks. Unfortunately, Qatar has refused to make public any meaningful data on migrant worker deaths, and heat regulations designed to protect workers from the dangers of extreme heat and humidity are still woefully inadequate.

MR: What are the main difficulties experienced by migrant workers involved in the construction industry in Qatar, particularly with respect to facilities being built for the 2022 FIFA World Cup?

HZ: Migrant workers traveling to Qatar and other countries in the Gulf region face abuses throughout their migration cycle. It starts in their home countries, where they often pay exorbitant recruitment fees just to secure jobs in Qatar, and often become heavily indebted in the process. When they arrive in Qatar, they are sometimes presented with contracts that pay less than they were promised.

Human Rights Watch research has also shown that abuses of migrant workers’ rights in Qatar are serious and systemic and that the violations often stem from its labor governance system known as kafala (sponsorship), which ties migrant worker’s legal status in the country to their employers. The system criminalizes “absconding,” that is, leaving an employer without permission, for example, to change jobs. Migrant workers are also often subjected to the routine confiscation of their passports by employers and pay recruitment fees to secure jobs in the Gulf, which can keep them indebted for years.

In conjunction with the prohibition on worker strikes and the ineffective implementation and enforcement of laws designed to protect migrant workers’ rights, these factors have contributed to abuse, exploitation, and even forced labor. Among migrant workers’ most common grievances are non-payment or delayed payment of wages, crowded and unsanitary living conditions, and excessive working hours. Construction workers and migrant workers in the service industry, including cleaners and security guards, are the most vital for hosting a successful World Cup and yet are among the most vulnerable to abuse and exploitation.

The Supreme Committee for Delivery and Legacy—the national body tasked with overseeing the organization of the FIFA World Cup 2022 in Qatar—has put in place additional protections specifically for migrant construction workers employed on stadium sites, which have led to better working conditions. But these protections only apply to about 28,000 workers—just under 1.5 percent of Qatar’s overall migrant population. They do not apply to workers building the metro system, the highways, parking lots, bridges, hotels, and other infrastructure projects essential for hosting the millions of visitors a World Cup will attract. They also exclude cleaners, restaurant staff, security guards, drivers, and stewards—men and women who will shoulder the hospitality sector’s efforts to accommodate the influx of people visiting the country. And even on stadium sites, workers have reported breaches of both Qatari law and the Supreme Committee’s additional protections.

MR: How have the Government of Qatar, FIFA, and others involved in the 2022 World Cup responded to the various criticisms about the treatment of migrant workers involved in the construction of World Cup facilities, and have the measures they have taken made a significant impact?

HZ: In October 2017, following several years of pressure by human rights organizations, media outlets, and international trade unions, Qatar promised to dismantle the kafala system, which gives employers excessive control over migrant workers’ legal status, and to implement other labor reforms as part of a three-year technical cooperation agreement with the International Labour Organization (ILO).

Since then, Qatar has introduced several reforms that chip away at abusive aspects of the kafala system and offer increased labor protections. The most significant of the reforms have been lifting the abusive exit permit requirement for most workers, which prevented migrants from leaving the country without their employer’s permission; allowing migrant workers to change jobs before the end of their contracts without first obtaining their employer’s consent; and a new law establishing a non-discriminatory basic minimum wage for all workers. Qatar also set up Labor Dispute Resolution Committees, designed to give workers a more efficient and faster way to pursue grievances against their employers; passed a law to establish a Workers’ Support and Insurance Fund, partly designed to make sure workers are paid unclaimed wages when companies fail to pay; and introduced amendments that set stricter penalties for employers who fail to pay their workers’ wages.

Yet migrant workers remain vulnerable to abuse and exploitation. Inadequate implementation and oversight of current legal provisions mean they rarely translate to worker protections in practice, and employers can pick and choose what protections to offer with relative impunity.

Other abusive elements of the kafala system also remain intact. For example, the minimum wage and increase in penalties for wage abuse, while positive, did not go far enough to eliminate wage abuse. An August 2020 Human Rights Watch report found that employers in Qatar frequently violated workers’ right to wages and that the Wage Protection System, introduced in 2015 and designed to ensure that migrant workers are paid correctly and on time, does not protect workers from wage abuses. It can be better described as a wage monitoring system with significant gaps in its oversight capacity. Wage protection measures have done little to protect workers from wage abuse.

MR: What key measures would need to be implemented to safeguard the rights and safety of these migrant workers?

HZ: Until Qatar dismantles the kafala system in its entirety and allows migrant workers to join trade unions and advocate for their own rights, workers are likely to continue to suffer abuses and exploitation. While some reforms have been introduced, key elements that facilitate abuse remain.

Migrant workers remain completely dependent upon their employers to facilitate entry, residence, and employment in the country, with employers responsible for applying for and renewing workers’ residency and work permits. Workers can find themselves undocumented through no fault of their own when employers fail to carry out these obligations, and it is the workers, not their employers, who suffer the consequences.

Qatar also continues to impose harsh penalties for “absconding”—when a migrant worker leaves their employer without permission or remains in the country beyond the grace period allowed after their residence permit expires or is revoked. Penalties include fines, detention, deportation, and a ban on re-entry.

These provisions can continue to drive abuse, exploitation, and forced labor practices, particularly as workers, especially laborers and domestic workers, often depend on employers not just for their jobs but for housing and food. In addition, passport confiscations, high recruitment fees, and deceptive recruitment practices are ongoing and largely go unpunished, and workers are prohibited from joining trade unions or engaging in strikes.

MR: How does the situation of migrant construction workers in Qatar compare with those involved in the construction industry in other Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states?

HZ: Qatar is not alone in its use of the kafala system to govern its migrant workforce. Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Oman, Bahrain, and Kuwait also have significantly large migrant worker populations and impose various forms of this system. While Qatar’s reform process has dominated international news, other governments too have declared their intention to restructure or reform their systems. However, these reforms only really tinker with the system and do little to dismantle it.

At present, migrant workers in all six countries remain tied to their employers in terms of entry into the country of destination, and the implementation of reforms that have already been adopted remains uneven across these countries. One of the most common violations of migrant workers’ rights in Gulf countries is employers’ failure to pay workers on time and in full, and low-paid migrant workers across the region remain acutely vulnerable to human rights abuses.

In 2015, in an effort to tackle the prevalent issue of wage abuse, Qatar introduced amendments to its labor law and unveiled the much-touted Wage Protection System (WPS), designed to ensure that employers pay wages to workers in compliance with the labor law. The WPS was originally created by the UAE in 2009, and today all the GCC countries except Bahrain have rolled out versions of the system, but its limitations have been exposed across these countries.

Another concern in all six GCC countries that specifically relates to construction workers and other workers laboring outdoors is the lack of adequate heat regulations to protect the lives of millions of migrant workers who do grueling work in often unbearably hot and humid weather conditions for up to twelve hours a day for six and sometimes even seven days a week.

All GCC countries operate similar summer working hours bans that are not linked to actual weather conditions and temperatures, and instead ban outdoor work during specific times of the day during the summer months. But climate data shows that weather conditions in Qatar and other Gulf countries outside those hours and dates frequently reach levels that can result in potentially fatal heat-related illnesses in the absence of appropriate rest. All six countries should do more to protect those building their infrastructure, shouldering their economies, and caring for their homes and children. The starting point is dismantling the kafala system and ending the prohibition on migrant workers joining trade unions.