Introduction

1. Genuinely Confront Allegations of International Crimes by US Personnel

2. Adopt a Constructive US Policy toward the ICC

a. Participate constructively in multilateral discussions about the ICC

b. Cooperate with ICC investigations and prosecutions as a rule, not an exception

c. Consider ICC investigations in Palestine and Afghanistan through the broader lens of the fight against impunity

d. Eliminate elements of a hostile legacy toward the ICC

3. Support Other Emerging Elements of the Global Accountability System

a. Support justice for serious crimes through domestic or hybrid courts

b. Support accountability through the United Nations

4. Strengthen and Support the Use of Universal Jurisdiction

5. Mainstream International Justice in Foreign Policy

a. Appoint a war crimes ambassador and expand the Office of Global Criminal Justice

b. Integrating justice approaches into atrocity prevention

Introduction

Given the proliferation of grave international crimes around the world[1] and the stated commitment of the United States to atrocity prevention and accountability,[2] effective initiatives by the administration of President Joe Biden on international justice are urgently needed. The previous administration’s dismissal of international justice through hostility toward the International Criminal Court (ICC), and disregard for core human rights principles has undermined the ability of the United States to fight impunity worldwide.

As an influential member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, then-Senator Biden was a vocal supporter of international criminal justice.[3] In his first foreign policy speech, President Biden signaled a much-needed renewed commitment to working with allies and participating in multilateral institutions.[4] This should extend to promoting justice for serious international crimes and a renewed engagement with the ICC.

Human Rights Watch urges the Biden administration to demonstrate a consistent and comprehensive commitment to justice for the worst international crimes. On a global landscape increasingly marked by disdain for the rule of law, the Biden administration should ensure that international justice is a key component of its embrace of multilateralism. Promoting accountability is critical for victims and survivors to obtain justice and plays a role in ending cycles of violence. Even without being a party to the Rome Statute, the US can be an important contributor to the work of the ICC if it does not let the court’s investigations in Afghanistan and Palestine interfere with its commitment to international justice.

This document offers the following recommendations to the Biden administration to promote international justice:

- Genuinely investigate and appropriately prosecute alleged international crimes by US personnel;

- Adopt a constructive relationship toward the ICC;

- Support credible domestic and hybrid war crimes courts and United Nations fact-finding and investigative bodies;

- Strengthen the domestic framework to prosecute serious crimes committed abroad; and

- Mainstream support for international justice across US foreign policy.

1. Genuinely Confront Allegations of International Crimes by US Personnel

It is crucial that President Biden pursue accountability for past US violations of human rights globally and commit to preventing future abuses. Failure to do so will diminish the ability of the United States to persuade other countries to seek accountability for grave crimes as international law requires. President Biden’s decision to withdraw all US combat troops from Afghanistan by the 20th anniversary of the September 11, 2001 attacks is an opportunity to finally and decisively address impunity for crimes committed by US personnel. The anniversary of those attacks provides a symbolic moment to acknowledge the 9/11 attacks as a widespread attack directed against US civilians, but also the violations that the US committed in response. The administration should speak publicly about its commitment to addressing detainee abuse, including torture and killings in custody, indiscriminate attacks on civilians, and unlawful targeted killings, including by conducting independent and impartial investigations and appropriate prosecutions.

Indeed, the Biden administration seems to recognize—at least in principle—that US credibility depends on addressing the US human rights record. As Secretary of State Antony Blinken has noted: “[W]e know we have work to do at home . . . and in fact, that’s exactly what separates our democracy from autocracies: our ability and willingness to confront our own shortcomings out in the open.” Now is the time to “lead by the power of our example” with respect to US accountability.[5]

The Biden administration should authorize the declassification of the report by the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence regarding the Central Intelligence Agency’s detention and interrogation program. The administration should also fully declassify the Rendition, Detention and Interrogation program, thereby facilitating civil claims by torture victims.[6]

In addition, the Biden administration should reexamine criminal prosecution for those who authorized and ordered unlawful conduct, including torture, in the “global war against terror.” The investigation conducted by Special Prosecutor John Durham was unnecessarily limited to investigating only those actions that exceeded the “legal authorizations” provided by George W. Bush administration officials at the time.[7] The investigation should be reopened to include conduct that was within the so-called authorizations but illegal under US and international law. Further, there is no indication that victims of abuses were interviewed, undermining the credibility of even that limited investigation.

While the US remains opposed to the ICC’s potential investigation into alleged crimes committed by US personnel in connection with the conflict in Afghanistan,[8] as detailed below, its best response would be to investigate these allegations and prosecute those responsible.[9] The Rome Statute of the ICC contains avenues for national authorities to challenge the court’s jurisdiction based on genuine domestic proceedings, consistent with the principle of complementarity. The abysmal US record on domestic proceedings provides the basis for ICC investigation of these very serious abuses. The US should cooperate with the ICC’s investigation into alleged crimes committed by US personnel in relation to the conflict in Afghanistan and with the broader ICC Afghanistan investigation.

The Biden administration should also close the US military prison at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, releasing to safe locations all those detainees who have not been credibly charged with criminal offenses. Those charged should be promptly prosecuted in a court system that meets internationally recognized fair trial standards, which the fundamentally flawed military commissions at Guantanamo do not meet. A part of that disposition should include full disclosure of any abuse perpetrated against the detainee whether before or while being held at Guantanamo, including any information about any steps taken towards accountability for that abuse.

The Biden administration should commit to holding US personnel accountable for violations of international law, should ensure prosecutions outside the regular US military chain of command, and emphasize the importance of adherence to the laws of armed conflict and accountability for violations. Ensuring a strong domestic accountability system should include a review of existing reporting mechanisms for alleged illegal conduct by US personnel as well as illegal conduct by partner forces that is observed or suspected.

Finally, while President Biden has announced “ending all American support for offensive operations in Yemen, including relevant arms sales,”[10] the US should make public further details of the US State Department Inspector General report “Review of the Department of State’s Role in Arms Transfers to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.”[11] The United States should investigate US officials for suspected complicity in war crimes in Yemen, given US sales of weapons to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates that may have been used in war crimes against civilians.[12]

2. Adopt a Constructive US Policy toward the ICC

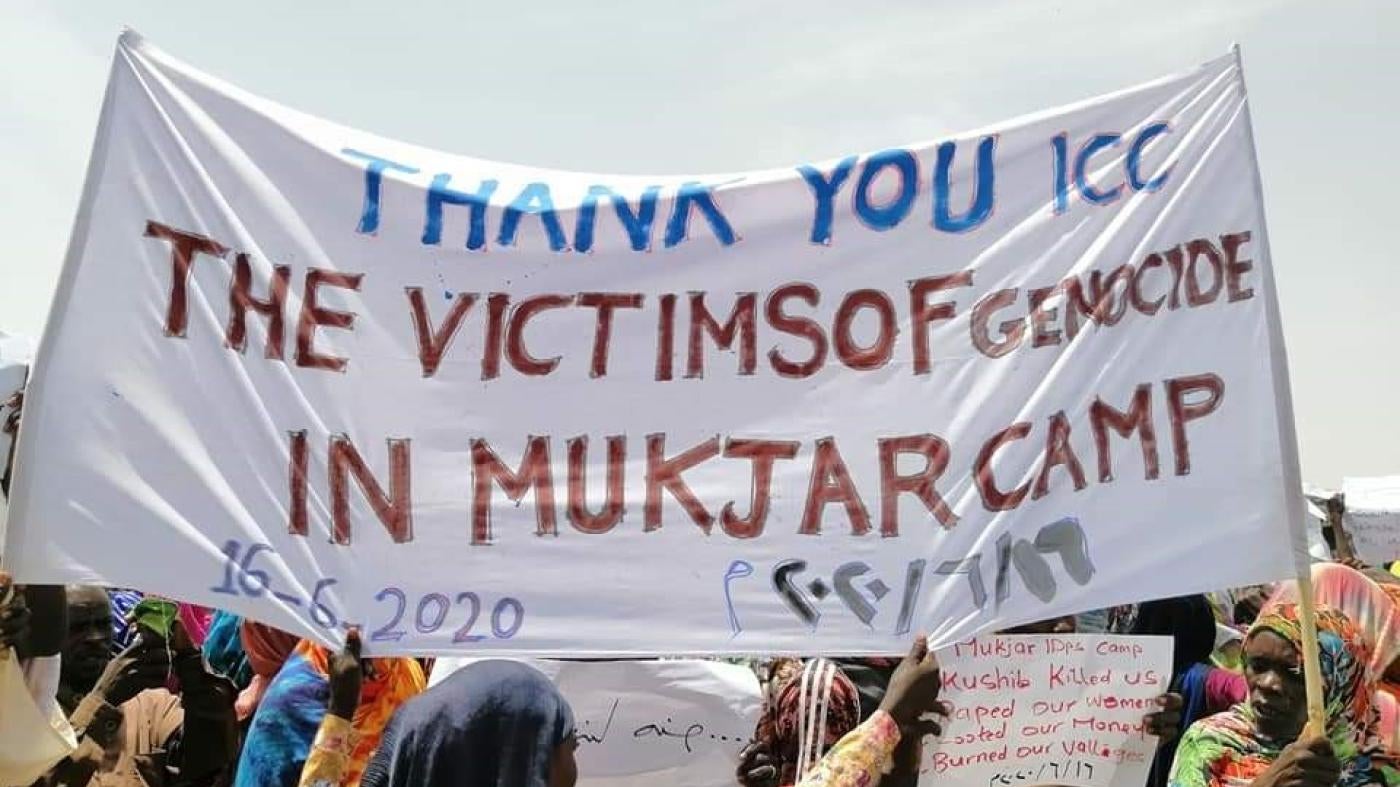

Although the ICC is not the only forum for international criminal accountability for the most serious crimes, it sits at the center of international justice efforts as its most ambitious and far-reaching institution and a court of last resort. Despite expressed bipartisan support for international justice, there remain longstanding US objections to ICC jurisdiction over nationals of non-states parties. The George W. Bush administration initially led a hostile campaign against the court, but later took a more constructive posture, notably when it did not veto a UN Security Council resolution requesting that the ICC prosecutor investigate crimes in Darfur. The Obama administration’s subsequent “case-by-case” policy of cooperation with the ICC was a good step toward justice for victims. The US voted in favor of a UN Security Council referral of the situation in Libya, played a critical role in the transfer to the court of two suspects, and expanded the US War Crimes Rewards Program to include ICC fugitives.[13] That program offers financial incentives for information leading to the arrest, transfer to, or conviction by international criminal tribunals.

The Trump administration aggressively reversed course, culminating in theJune 2020 executive orderauthorizing asset freezes and entry bans aimed at thwarting the ICC’s work and the use of this order to impose sanctions on the court’s prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda, and another senior official, Phakiso Mochochoko, in September 2020.[14] On April 2, 2021, the Biden administration revoked the executive order and associated sanctions.[15] In removing these sanctions, President Biden has begun what could be the long overdue process of restoring US credibility on international justice.

While differences, currently centered on investigations in Palestine and Afghanistan, will remain between Washington and the court, the United States should now (a) participate constructively in multilateral discussions about the ICC, (b) regularize its cooperation with the ICC’s investigations and prosecutions, (c) view the ICC’s Afghanistan and Palestine investigations through a broader lens of the fight against impunity, and (d) eliminate legacy tools, such as legislation that could undermine cooperation with the court. While acceding to the Rome Statute may not be in the administration’s sights, constructive engagement with the court can pave the way to this longer-term and ultimate goal.

a. Participate constructively in multilateral discussions about the ICC

Secretary Blinken stated that the United States “will bring to bear all the tools of our diplomacytodefend human rights and hold accountable perpetrators of abuse” and that it is “committed to working with its allies and partners to hold the perpetrators of these abhorrent acts accountable.”[16] The ICC is the principal tool for achieving this end, with 123 member countries, including many US allies, including nearly all of its NATO partners as well as some of its principal non-NATO allies.

While developing a modus operandi for engagement with the court in what may be contentious areas, the Biden administration can take steps in the near-term to restore an overall constructive approach that will simultaneously enhance US credibility on human rights in US foreign policy.

As one step, the Biden administration should return to participation in the next annual session of the member countries of the ICC, known as the Assembly of States Parties, in December 2021, as an observer state. At the same time, it will be important for the administration to be mindful of the US’s status as a non-state party—thus, its observer state status—and engage in sessions in a manner that respects the Rome Statute and promotes its goals.

ICC member countries and court officials are currently assessing and considering the potential implementation of recommendations stemming from a review of the court’s performance by a group of independent experts, as well as holding additional discussions as part of a broader review.[17] Secretary Blinken said that “this reform is a worthwhile effort.”[18] But the review process is aimed at strengthening the court’s delivery of justice and should not be used to undercut the court’s reach and its independence as a judicial institution. As a non-party—and one with a recent history of hostility towards the court—US participation should not be a Trojan horse that comes at the expense of the court’s mandate.[19] Instead, to the extent it engages in the review process, the United States should be focused on contributing to efforts to strengthen cooperation between states and the court as well as promoting assistance between governments to support domestic capacity for the effective prosecution of serious international crimes, known as “positive complementarity.” Such engagement will begin to repair the US relationship with its allies and the court.

b. Cooperate with ICC investigations and prosecutions as a rule, not an exception

A US State Department spokesperson indicated that the Biden administration may consider resuming cooperation with the court in “exceptional cases.”[20] In our view, this would fall far short of committing to advancing accountability for the most serious crimes. For the administration’s support for international justice to carry legitimacy, its cooperation with the ICC should be the rule, not the exception.

Advancing accountability in ICC country situations is consistent with stated US foreign policy objectives, including “support for the rule of law, access to justice, and accountability for mass atrocities.”[21] The United States provided essential support in the surrender to the court of Bosco Ntaganda, a rebel leader from the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, in 2013, and Dominic Ongwen, a former leader of the brutal Lord’s Resistance Army, in 2015. Ongwen was convicted on February 4, 2021,[22] a development which the Biden administration welcomed,[23] and was then sentenced to 25 years’ imprisonment.[24] These cases highlight the very constructive role that the US can play with the court.

Given the deficit in global cooperation with the ICC, we urge the Biden administration to continue to facilitate and press for the arrest of individuals sought by the court. Support in the arrest of suspects is crucial. Without its own police force, the ICC relies on states for cooperation in arrests, and that cooperation has been inadequate. Arrest warrants remain outstanding against a number of individuals. The United States has a role to play, as it did with the prior transfer of two ICC suspects, to ensure that those wanted by the court are brought to the dock. The administration should encourage other governments to cooperate with the ICC in ensuring the arrest and surrender to the court of ICC fugitives, share intelligence and provide other practical support to arrest operations, and expand its War Crimes Rewards Program to cover all ICC suspects.[25] It could also work to ensure that UN peacekeeping operations in countries where the ICC is conducting investigations are mandated to assist the court, including in arrests.

The United States can build on its prior support for the arrest and surrender of suspects wanted for atrocities, including the former Sudanese president, Omar al-Bashir, Lord’s Resistance Army leader Joseph Kony, and individuals sought in connection with the Libya situation.

Beyond cooperation for arrest and surrender, the Biden administration can provide the ICC with much-needed assistance given the ICC’s budgetary limitations. The United States should share relevant and lawfully obtained information and evidence. It should also support appropriate Security Council resolutions on the ICC, such as those referring cases to the court or calling for cooperation with the ICC. The Biden administration’s recent expression of support for the Darfur and Libya investigations in statements to the Security Council are particularly welcome.[26] The United States should join the General Assembly’s annual consensus resolution on the ICC and not dissociate from other UN resolutions that bear on accountability simply because of a reference to the ICC. At the Human Rights Council, the US should support initiatives aimed at bolstering the ICC’s role. The Biden administration should also consider contributing to the ICC’s Trust Fund for Victims, which is an entity distinct from the court and thus not subject to legislative funding restrictions.

c. Consider ICC investigations in Palestine and Afghanistan through the broader lens of the fight against impunity

While lifting the Trump administration sanctions, the Biden administration made clearthat the United States continues to oppose the “ICC’s actions” in the Afghanistan and Palestine situations, and more generally, any ICC jurisdiction over the nationals of non-states parties.[27] The Biden administration should reconsider this position.

The Rome Statute provides for jurisdiction over nationals of non-states parties when alleged abuses are committed in ICC member countries. There is nothing unusual about this: US citizens who commit crimes abroad are already subject to the jurisdiction of foreign courts, including pursuant to many international treaties, and the ICC draws from that authority.[28] There is no principled reason for the United States’ objection.

Particularly given the US government’s minimal efforts to hold US personnel accountable for alleged crimes committed in Afghanistan, the objection on jurisdictional grounds serves as a demand for impunity. The authorized scope of the ICC’s Afghanistan investigation is much broader than the crimes allegedly committed by US personnel, encapsulating the alleged crimes committed on a larger scale by Afghan government and Taliban forces against civilians.[29] Accountability could help bolster efforts to promote durable peace in the country.[30] Impunity for a subset of those accused of crimes risks further entrenching the notion of unequal justice.

Similarly, the court’s Palestine investigationprovides a long-awaited path to justice for both Palestinian and Israeli victims of serious international crimes.[31] US objections to this investigation—including because of its position that Palestine is not a state, that an investigation could undermine the peace process, and its stated support for Israel[32]—should not stand in the way of justice for victims.[33]

The Biden administration should articulate its disagreements with the court’s investigations in accordance with the rule of law and procedures under the Rome Statute.[34] Ultimately, the best way to preempt ICC scrutiny and protect US national interest is by genuinely investigating and appropriately prosecuting alleged crimes committed by US nationals in connection with the Afghanistan conflict. As noted above, the US’s record on accountability for abuses committed there is poor. If the US conducts genuine proceedings relevant to cases the ICC prosecutor is likely to pursue in Afghanistan, it would be much better positioned to challenge the admissibility of cases before the court. But while impunity persists, the ICC has a mandate to ensure that victims of grave crimes have a path to justice.The administration should consider outreach to members of Congress and the American public to explain why credible accountability (even if it requires an ICC investigation) is, in fact, in the best interest of the US, as well as necessary to meet victims’ rights to access justice.

d. Eliminate elements of a hostile legacy toward the ICC

The Biden administration should also eliminate relics of the hostile legacy of prior US administrations toward the ICC. This includes repealing the remaining provisions of the American Servicemembers’ Protection Act (ASPA).[35] Numerous US government officials have expressed concern about the impact of ASPAon foreign relations, including President Biden who voted against ASPA as a senator and said: “I do not want to harm U.S. interest overseas. Many of our closest allies in Europe are strong supporters of this Court. This legislation will further complicate our relationship with those friends. Moreover, it takes aim at allies outside of Europe with punitive measures.”[36]

While ASPA has been watered down by amendments removing restrictions on military education and training for all nations and on foreign military financing for nations refusing to agree to bilateral immunity agreements, opposition to all remaining provisions ofASPA—including to its infamous so-called “Hague invasion” provision—and other legislation that restricts cooperation with or funding to the ICC is needed.[37]

Similarly, for several years, the George W. Bush administration sought to force ICC member countries to choose between their obligations under the ICC statute and significant military and financial aid cuts if they refused to sign bilateral immunity agreements with the United States. While this policy was abandoned by Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice,[38] these agreements are still in force and they should be formally rescinded.

3. Support Other Emerging Elements of the Global Accountability System

Over the past three decades, there have been significant advances in closing the accountability gap for the gravest crimes through international, hybrid, and domestic courts, along with various fact-finding and investigative bodies. Together with the ICC, these are important components of the emerging “system” of international justice. The United States has been supportive of many of these mechanisms and should continue to provide political support and resources for these efforts, particularly as the international geopolitical landscape in support of international justice efforts has deteriorated.

a. Support justice for serious crimes through domestic or hybrid courts

Where national and hybrid courts undertake efforts that can fairly and effectively hold perpetrators to account, they should be reinforced. We urge the Biden administration to financially and politically support credible national and hybrid efforts to prosecute serious crimes. This should include support for civil society organizations, which play a critical role in promoting effective national and international justice efforts, through documentation, legal analysis, litigation, advocacy, and monitoring. Support should help address security and protection issues that often arise for justice advocates.[39]

Below are non-exhaustive highlights of some country-specific recommendations, with further information available at the provided links. Human Rights Watch can provide further information on any of these recommendations.

Africa

- Cameroon: Press authorities to ensure accountability for abuses by both government forces and armed groups. Consider halting military assistance to Cameroonian security forces pending inquiries into abuses and impose targeted sanctions on perpetrators.

- Central African Republic: Continue to provide financial support for the Special Criminal Court, a new war crimes court based in the country’s capital, Bangui, which is staffed by international and national judges and prosecutors.

- Democratic Republic of Congo: Continue to support domestic accountability efforts. Press for the establishment of an internationalized mechanism to investigate and prosecute serious crimes and provide support for its operationalization. Press for the creation of a mechanism to remove abusive commanders from the security forces.

- Guinea: Press for the commencement of Guinea’s trial of crimes committed during Guinea’s 2009 stadium massacre.

- Kenya: Support thegovernment to develop and implement a reparations programfor victims of human rights violations committed during the2007-08post-election violence.

- Liberia: Press for the establishment of a war crimes court to prosecute atrocities committed during Liberia’s successive civil wars.

- South Sudan: Press the government and the African Union for the speedy establishment of the proposed Hybrid Court for South Sudan and continue to provide financial support for its operationalization and functioning.

- Sudan: Press for fair, credible domestic trials of past serious crimes committed in the country, including in Darfur, Blue Nile, and Southern Kordofan.

- Uganda: Press for improvement in the practice of the domestic International Crimes Division to bring fair, credible, justice for serious crimes committed.

Americas

- Colombia: Support the Special Jurisdiction for Peace, while engaging with the jurisdiction’s authorities to ensure that they deliver meaningful justice for war crimes committed by all sides of the conflict, and monitoring any attempts to undermine the genuineness of proceedings, including from the governing party, the Democratic Center.

- Guatemala: Continue to support and promote accountability and investigation of corruption and human rights violations, strengthen the role of the Prosecutor’s Office against Impunity, and promote fair and transparent selection of judges.[40]

- Venezuela: Continue to promote accountability efforts in Venezuela, includingthe preliminary examination by the ICC prosecutor and investigations by the United Nations appointed Fact-Finding Mission on Venezuela and reporting by the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights.

Europe/Central Asia

- Belarus: Continue support for the International Accountability Platform for Belarus.

- Georgia: Press relevant authorities in Georgia and Russia to cooperate with the ICC investigation and support national efforts to address additional accountability needs in connection with the 2008 Georgia-Russia conflict over South Ossetia.

- Kosovo: Continue US financial and political support for the Kosovo Specialist Chambers and Specialist Prosecutor’s Office, currently run by a US chief prosecutor.

- Ukraine: Provide expertise in investigations and prosecutions regarding conflict-related abuses in eastern Ukraine and Crimea.

Middle East/North Africa

- Iraq: Press authorities to hold perpetrators of serious crimes accountable, including state forces in credible proceedings. Monitor and press for improvement in criminal proceedings, particularly in trials of ISIS suspects. Consider a broader accountability process, including a non-judicial mechanism for those suspected only of ISIS membership without evidence of any other serious crime.

- Libya: Press for credible accountability to hold perpetrators of serious crimes on all sides to account, regardless of their rank or title.

b. Support accountability through the United Nations

Unfortunately, there are (and will continue to be) situations where there may not be a clear avenue for justice for serious international crimes at the national or international level. The United States should innovate with partners on filling this part of the accountability gap, including by supporting UN-mandated bodies that can lay the groundwork for future criminal justice, such as the investigative mechanisms created for Syria and Myanmar. It should also support the ongoing work of the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) in its documentation of mass atrocities.

Alongside these efforts, the Biden administration should also press for debates and resolutions on serious human rights violations in various UN forums and push for accountability where gaps exist.

Now that it has re-engaged with the UN Human Rights Council and has expressed its intent to seek election for a seat on the council, the Biden administration should also continue to support existing fact-finding bodies, commissions of inquiry, and special procedures on various country situations where serious crimes are ongoing. Examples include Israel/Occupied Palestinian Territory, Libya, Myanmar, Philippines, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, Syria, Venezuela, and Yemen.

i. Syria and Myanmar

The Biden administration should continue to support UN-mandated investigative mechanisms established for crimes allegedly committed in Syria (theInternational, Impartial and Independent Mechanism(IIIM)) and Myanmar (the Independent Investigative Mechanism for Myanmar(IIMM)).[41]

The Biden administration should provide political, material, technical, and financial support to those mechanisms as appropriate. It should cooperate with those investigations and share any relevant information and material to support their ongoing investigations.

But these mechanisms are not sufficient and other complementary steps should be taken to ensure that their investigative work can feed into a credible judicial process, including through domestic criminal cases using the principle of universal jurisdiction.

The Biden administration can also use its permanent seat on the Security Council (together with like-minded governments on the council) to encourage debates on Syria’s and Myanmar’s human rights records and work toward concrete action to end violations and bring about accountability.

ii. China

The Biden administration should move swiftly to support the establishment of an ongoing mandate to monitor and regularly report on the Chinese government’s human rights violations to the Human Rights Council, as urged in June 2020 by an unprecedented group of 50 UN human rights experts.

In particular, the US government should support an independent, council-mandated investigation into the detention of more than a million Uyghur and other Turkic Muslims in the Xinjiang region. The Biden administration’s use of the term “genocide” to describe the situation in Xinjiang has raised expectations considerably among various communities that the United States will use its influence to seek accountability. Until such a body can be established, the US should press the OHCHR to continue monitoring and reporting in accordance with its independent protection mandate.

iii. Ethiopia

The Biden administration has recently demonstrated the concern it accords to the crisis in Ethiopia’s Tigray region, including calling for an independent investigation into alleged atrocities committed since November 2020.[42]

It should make Ethiopia a priority of its renewed engagement at the Human Rights Council. The OHCHR is conducting joint investigations with the country’s national human rights institution, although that body’s ability to exert complete independence and the communities’ trust in it still need to be tested. The US should continue to call on the Ethiopian government to allow full, unrestricted access for OHCHR to conduct its own investigation into war crimes and possible crimes against humanity in the Tigray region, to collect and preserve evidence of international crimes, and pave the way for accountability. The US should join efforts, including by the European Union, to ensure that Ethiopia is on the Human Rights Council agenda with the aim of pushing for a full, independent, OHCHR investigation, as well as requesting that the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights regularly briefs member states on the ongoing crisis.

African Union mechanisms have by and large been silent, or absent. The Ethiopian leadership has rejected efforts of mediation and resolution of the conflict from both the African Union as well as the UN. Positively, on May 12, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR) adopted an important resolution establishing a commission of inquiry to investigate violations of international humanitarian and human rights law and identify perpetrators.[43] It is unclear how the ACHPR’s inquiry will interact and coordinate its investigative efforts with the UN. The US should engage with the ACHPR inquiry, including regarding mandate and expertise, request coordination between the two initiatives, and call on the Ethiopian government to allow access for the ACHPR investigators.

The Ethiopian government has announced the domestic prosecution of Ethiopian military officers for sexual violence and rape and the killing of civilians during the conflict. The US government should call on the government to conduct these trials in civilian courts, guarantee witness protection, and ensure transparency of these ongoing trials.

iv. North Korea

The Biden administration should re-prioritize human rights in North Korea. For several years after the 2014 UN Commission of Inquiry report on human rights in North Korea, there was increased attention on North Korea’s human rights record at the UN Security Council. During those debates, some member countries even raised the idea of a formal Security Council resolution referring the situation in North Korea to the ICC. The United States should use its seat at the Security Council to re-establish regular discussions on North Korea’s human rights record as a critical component of any assessment of the risk posed by Pyongyang on the Korean peninsula and the region.

The OHCHR currently has an office in Seoul to gather information for use in future prosecutions. The administration should engage with the UN General Assembly member states to support the mandate of the accountability project on North Korea at the OHCHR, and expand its mandate to be aligned with the other international mechanisms, to collect and preserve evidence of international crimes.

v. Philippines

There is increasing concern over extrajudicial executions and other serious human rights violations in the context of the Duterte government’s “war on drugs.” In October 2020, instead of launching a much-needed independent international investigation, the Human Rights Council passed a resolution requesting the OHCHR to provide “technical assistance” for domestic investigative and accountability measures and report to the council for two more years. This response was clearly inadequate given that the government is the architect and implementer of the abusive policies in question, coupled with its refusal to acknowledge the scope and scale of extrajudicial executions.

To bring heightened scrutiny to the human rights situation in the Philippines, the United States should work actively to form a core group of states to establish an international investigative mechanism through the Human Rights Council, with a view to ending violations and ensuring accountability. Such a mechanism could in turn support efforts by the ICC, following the May 2021 request by the ICC prosecutor for authorization to investigate. A UN-mandated investigation is especially crucial to address crimes given the Philippines’ effective withdrawal from the ICC on March 17, 2019.

Congress has introduced thePhilippine Human Rights Act, which seeks to suspend US defense and security assistance to the Philippines for abuses until the government undertakes significant reform.[44] Secretary Blinken should maintain the suspension until there is genuine progress on accountability.

vi. Sri Lanka

Fundamental human rights protections in Sri Lanka have been in serious jeopardy following Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s election as president in November 2019. In February 2020, Sri Lanka withdrew its commitments to justice and accountability made at the Human Rights Council in 2015 to address war crimes and other grave violations committed during and since the civil war between the government and the separatist Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), which ended in 2009.

At its 46th session ending in March 2021, the council adopted a resolution mandating the OHCHR to “collect, consolidate, analyse and preserve information and evidence,” to develop “strategies for future accountability processes,” and to “support relevant judicial and other proceedings.” In addition to supporting the OHCHR, the United States should implement the recommendations of UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Michele Bachelet that governments should “actively pursue investigation and prosecution of international crimes committed by all parties in Sri Lanka before their own national courts,” and explore “targeted sanctions, such as asset freezes and travel bans against credibly alleged perpetrators of grave human rights violations and abuses.”[45]

4. Strengthen and Support the Use of Universal Jurisdiction

National courts of an increasing number of European countries have exercised universal jurisdiction over individuals suspected of committing serious international crimes,[46] including for crimes committed in Syria drawing on evidence gathered by the IIIM. These cases have been crucial in beginning to address the large accountability gap in the face of formidable limitations in national courts’ jurisdictional reach and limited resources.

In contrast, the United States appears to be lagging behind in pursuing cases against alleged perpetrators of atrocity crimes committed abroad, despite having several federal statutes that authorize prosecutions for genocide, war crimes, torture, and the recruitment and use of child soldiers (among others)[47] and the comparatively large resources of the Department of Justice (DOJ). Effective leadership by the Biden administration could make a real difference in spurring more cases of this kind.

The US government has relied mostly on immigration laws for the prosecution or deportation of foreign nationals who are also implicated in serious international crimes,[48] instead of prosecuting them for the underlying substantive crime. We urge the Biden administration to encourage the DOJ to actively apply laws that allow US courts to prosecute alleged human rights abusers, where possible. This includes assessing the obstacles that may exist to more prosecutions and increasing resources and coordination among relevant government agencies.The indictment of Michael Sang Correa of Gambia in June 2020 under the US torture statute[49] is a welcome development in this regard and his trial should lay the groundwork for more frequent application of the relevant US statutes. Inside the DOJ, the Human Rights and Special Prosecutions Section is mandated precisely to conduct this type of prosecution. Using DOJ resources to implement these statutes would constitute a significant step in reestablishing and bolstering US commitment to international justice among states that are at the forefront of universal jurisdiction efforts (as well as others).

The administration should also press for Congress to close key loopholes that persist in the statutory framework on serious international crimes.[50]For instance, the war crimes statute has limited jurisdictional reach, extending only to cases in which the alleged perpetrator or victim is a US national, and thus not reaching alleged suspects present on the territory of the United States irrespective of nationality. Another blind spot is the complete lack of any express legislation on crimes against humanity.

In parallel to working to bolster domestic legislation, the Biden administration should also promote potential multilateral treaties on international crimes, specifically the International Law Commission’s Draft Articles on the Prevention and Punishment of Crimes Against Humanity,[51] presently under consideration by the Sixth Committee of the UN General Assembly. It has been observed that the United States is one of only five states that seems to have developed a more negative view of the Draft Articles in the last four years.[52] We urge the Biden administration to take a more positive approach in any future negotiations on the Draft Articles, including by opposing any regressive steps on previously codified definitions of crimes against humanity. The United States should also constructively engage in diplomatic negotiations about a proposed treaty on Mutual Legal Assistance for all atrocity crimes.[53]

In addition, the United States should also provide support for credible investigations pursued on the basis of universal jurisdiction where possible, including through cooperation, information-sharing, and intelligence, to national judicial authorities as they build these cases. One forum for strengthened engagement, already attended by DOJ prosecutors, is the European Network for investigation and prosecution of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes (Genocide Network), which meets in The Hague twice a year. Any cooperation should be done in a way that is consistent with US human rights obligations and ensures that partners’ conduct is consistent with international human rights law.

5. Mainstream International Justice in Foreign Policy

To achieve the objectives outlined above, the Biden administration should mainstream support for justice for serious international crimes across foreign policy, as it also pursues accountability for US abuses, as discussed above.

a. Appoint a war crimes ambassador and expand the Office of Global Criminal Justice

The Clinton administration created the position of Ambassador-at-Large for Global Criminal Justice (previously for War Crimes Issues) and a functional Office of Global Criminal Justice (OGCJ) dedicated to the prevention of, response to, and accountability for atrocity crimes.[54] At times in the past, going back to its creation, the position of Ambassador-at-Large was hugely important in both symbolizing and implementing US commitment to accountability. Under the Trump administration, the office’s very existence was threatened.[55]

The Biden administration should promptly appoint and seek Senate confirmation of a new Ambassador-at-Large for Global Criminal Justice. The standing, expertise, and commitment of this individual is crucial to their success. The office should be bolstered with additional staff to support its broad mandate, as international justice mechanisms and pathways have multiplied. The 2021 Consolidated Appropriations Act committed at least $10 million to the office to administer to accountability programs.[56] These funds can provide critical contributions to support domestic and international authorities in the investigation and prosecution of serious international crimes, providing a more focused approach than available through other streams of US funding in support of broader rule-of-law objectives.

The OGCJ can also continue coordination across agencies to ensure a whole-of-government approach to promoting justice and accountability, and work to promote engagement and transparency with partners. For example, the office could convene regular roundtable discussions with relevant stakeholders, including the Justice Department’s Human Rights and Special Prosecutions Section and civil society groups, to promote an exchange of views on supporting a range of national and international justice efforts. The Department of Defense should also ensure that promotion of justice and accountability are key components of its partner relationships, and coordinate with OGCJ and others as appropriate to promote security sector reform to prevent abuses.

b. Integrating justice approaches into atrocity prevention

In recent years, the US government (during both Democratic and Republic administrations) has expressed a national interest in the prevention of mass atrocities and created an interagency framework to address this priority. President Barack Obama established the Atrocities Prevention Board in 2012, with a primary mission “to coordinate a whole-of-government approach to preventing mass atrocities and genocide.” In 2018, Congress adopted the Elie Wiesel Genocide and Atrocities Prevention Act (the Elie Wiesel Act), which identifies atrocity prevention and response as a critical US national security interest and institutionalizes interagency coordination.[57] In December 2019, the Global Fragility Act similarly mandated interagency cooperation to help stabilize conflict-affected areas.[58] The Atrocities Prevention Board was later renamed the Atrocity Early Warning Task Force (the Task Force) under the Trump administration.

Although there has been progress institutionalizing statutory requirements on atrocity prevention, there is significant room for improvement, particularly to ensure effective implementation of the Elie Wiesel Act and to incorporate international justice. The Prevention and Protection Working Group, a coalition of civil society organizations dedicated to improving US policies on atrocity prevention,[59] has made important recommendations.

In particular, there is a need to “enhance public messaging on the U.S. government’s atrocity prevention work,” as recommended in the 2020 Report to Congress pursuant to the Elie Wiesel Act.[60] The Task Force should release the list of countries designated at-risk, as required by the act, and publicly report on the Task Force’s work. It should also publicize and depoliticize the process by which the US government determines if an atrocity crime is occurring, including making public identifying factors.[61] Justice considerations should be included as a risk factor, since impunity fuels further atrocities and cycles of violence (as is now unfolding in Myanmar).

Finally, Congress also has an important role to play by convening briefings and hearings on atrocity situations, including the Executive Branch’s annual briefing under the Elie Wiesel Act. These yearly reports should integrate transitional justice and accountability, and be transparent and straightforward about the ICC’s involvement in relevant situations.

[1] United Nations at 75, “A New Era of Conflict and Violence,” undated, https://www.un.org/en/un75/new-era-conflict-and-violence (accessed May 27, 2021).

[2] See “Ending Sanctions and Visa Restrictions against Personnel of the International Criminal Court,” US Department of State press statement, April 2, 2021, https://www.state.gov/ending-sanctions-and-visa-restrictions-against-personnel-of-the-international-criminal-court/ (accessed May 18, 2021).

[3] “Participants Biographies: 2006 Human Rights Defender’s Forum,” see biography of Joseph Biden, https://www.cartercenter.org/documents/nondatabase/2006BIOS.pdf (accessed May 18, 2021).

[4] “Remarks by President Biden on America’s Place in the World,” February 4, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2021/02/04/remarks-by-president-biden-on-americas-place-in-the-world/ (accessed May 18, 2021).

[5] “Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken On Release of the 2020 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices,” US Department of State remarks to the press, March 30, 2021, https://www.state.gov/secretary-antony-j-blinken-on-release-of-the-2020-country-reports-on-human-rights-practices/ (accessed May 18, 2021).

[6] See Andrea Prasow (Human Rights Watch), “Declassify the Post-9/11 Torture Program,” commentary, The Hill, January 25, 2021, https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/01/25/declassify-post-9/11-torture-program.

[7] See Laura Pitter (Human Rights Watch), “Delusion of Justice on CIA Torture,” commentary, The Hill, December 14, 2015, https://www.hrw.org/news/2015/12/14/delusion-justice-cia-torture.

[8] See generally “Situation in the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan,” International Criminal Court (ICC), https://www.icc-cpi.int/afghanistan (accessed May 19, 2021).

[9] Elizabeth Evenson and Andrea Prasow (Human Rights Watch), “Why the US should be supporting, not undermining, international justice,” Responsible Statecraft, March 27, 2020, https://responsiblestatecraft.org/2020/03/27/why-the-us-should-be-supporting-not-undermining-international-justice/ (accessed May 19, 2021).

[10] See Afrah Nasser, “US Resuming Arms Sales to UAE is Disastrous,” Human Rights Watch dispatch, April 15, 2021, https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/04/15/us-resuming-arms-sales-uae-disastrous.

[11] Office of the Inspector General, US Department of State, “Review of the Department of State’s Role in Arms Transfers to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates,” August 2020, https://www.oversight.gov/sites/default/files/oig-reports/ISP-I-20-19.pdf (accessed May 28, 2021).

[12] Andrea Prasow (Human Rights Watch), “U.S. War Crimes in Yemen: Stop Looking the Other Way,” commentary, Foreign Policy in Focus, September 21, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/09/21/us-war-crimes-yemen-stop-looking-other-way.

[13] “War Crimes Rewards Program,” US Department of State, https://2009-2017.state.gov/j/gcj/wcrp/index.htm (accessed May 19, 2021).

[14] See Human Rights Watch, “Q&A: The International Criminal Court and the United States,” September 2, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/09/02/qa-international-criminal-court-and-united-states#8; “US Sets Sanctions Against International Criminal Court,” Human Rights Watch news release, June 11, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/06/11/us-sets-sanctions-against-international-criminal-court; “US Sanctions International Criminal Court Prosecutor,” Human Rights Watch news release, September 2, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/09/02/us-sanctions-international-criminal-court-prosecutor.

[15] “US Rescinds ICC Sanctions,” Human Rights Watch news release, April 2, 2021, https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/04/02/us-rescinds-icc-sanctions.

[16] “Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken On Release of the 2020 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices,” US Department of State remarks to the press.

[17] Independent Expert Review of the International Criminal Court and the Rome Statute System, “Final Report,” September 30, 2020, https://asp.icc-cpi.int/iccdocs/asp_docs/ASP19/IER-Final-Report-ENG.pdf (accessed May 19, 2021).

[18] “Ending Sanctions and Visa Restrictions against Personnel of the International Criminal Court,” US Department of State press statement.”

[19] See generally Elizabeth Evenson and Esti Tambay (Human Rights Watch), “The US Should Respect the ICC’s Founding Mandate,” commentary, Just Security (blog), May 19, 2021, https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/05/19/us-should-respect-iccs-founding-mandate.

[20] Simon Lewis, “Biden administration to review sanctions on International Criminal Court officials,” Reuters, January 26, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-biden-icct/biden-administration-to-review-sanctions-on-international-criminal-court-officials-idUSKBN29V2NV (accessed May 19, 2021).

[21] “Ending Sanctions and Visa Restrictions against Personnel of the International Criminal Court,” US Department of State press statement.

[22] “Uganda: First ICC Conviction of an LRA Leader,” Human Rights Watch news release, February 4, 2021, https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/02/04/uganda-first-icc-conviction-lra-leader.

[23] “Welcoming the Verdict in the Case Against Dominic Ongwen for War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity,” US Department of State press statement, February 4, 2021, https://www.state.gov/welcoming-the-verdict-in-the-case-against-dominic-ongwen-for-war-crimes-and-crimes-against-humanity (accessed June 15, 2021).

[24] “Dominic Ongwen sentenced to 25 years of imprisonment,” ICC press release, ICC-CPI-20210506-PR1590, May 6, 2021, https://www.icc-cpi.int/Pages/item.aspx?name=pr1590 (accessed May 19, 2021).

[25] The relevant legislation was expanded in 2013 to authorize rewards for information leading to the arrest, transfer to, or conviction by any “international criminal tribunal,” which would include the ICC. See Department of State Rewards Program Update and Technical Corrections Act of 2012, S. 2318, https://www.congress.gov/bill/112th-congress/senate-bill/2318 (accessed June 8, 2021). The State Department has so far designated Joseph Kony, Okot Odhiambo, Dominic Ongwen, and Bosco Ntaganda (Ongwen and Ntaganda were subsequently surrendered to the ICC, and Odhiambo is deceased). See “Fugitives from Justice (Submit a Tip),” US Department of State, https://2009-2017.state.gov/j/gcj/wcrp/c56848.htm (accessed June 8, 2021).

[26] “Remarks at a UN Security Council Briefing by the ICC Prosecutor on Sudan,” United States Mission to the United Nations, June 9, 2021, https://usun.usmission.gov/remarks-at-a-un-security-council-briefing-by-the-icc-prosecutor-on-sudan (accessed June 15, 2021); “Remarks by Ambassador Linda Thomas-Greenfield at a Security Council Briefing on Libya,” United States Mission to the United Nations, May 21, 2021, https://usun.usmission.gov/remarks-by-ambassador-linda-thomas-greenfield-at-a-security-council-briefing-on-libya (accessed June 15, 2021).

[27] “Ending Sanctions and Visa Restrictions against Personnel of the International Criminal Court,” US Department of State press statement.

[28] See Kenneth Roth (Human Rights Watch), “Biden’s Next Steps on Human Rights: Multilateral Institutions,” commentary, Newsweek, February 17, 2021, https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/02/17/bidens-next-steps-human-rights-multilateral-institutions; Human Rights Watch, “The ICC Jurisdictional Regime; Addressing U.S. Arguments,” undated, https://www.hrw.org/legacy/campaigns/icc/docs/icc-regime.htm.

[29] In March 2020, the government of Afghanistan requested a deferral of the prosecutor’s investigation under Article 18 of the Rome Statute, which is still under review at the time of this writing. See Situation in the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, ICC, No. ICC-02/17, Notification to the Pre-Trial Chamber of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan’s letter concerning article 18(2) of the Statute, April 15, 2020, https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/cqiv2p/ (accessed June 15, 2021).

[30] See Elizabeth Evenson and Andrea Prasow (Human Rights Watch), “Why the US should be supporting, not undermining, international justice.”

[31] “Israel/Palestine: ICC Judges Open Door for Formal Probe,” Human Rights Watch news release, February 6, 2021, https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/02/06/israel/palestine-icc-judges-open-door-formal-probe.

[32] See “The United States Opposes the ICC Investigation into the Palestinian Situation,” US Department of State press statement, March 3, 2021, https://www.state.gov/the-united-states-opposes-the-icc-investigation-into-the-palestinian-situation/ (accessed May 19, 2021).

[33] Balkees Jarrah, Human Rights Watch dispatch, “Gaza Hostilities Underscore ICC’s Role,” May 20, 2021, https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/05/20/gaza-hostilities-underscore-iccs-role.

[34] See generally Thierry Cruvellier, “How Biden’s America Can Reverse Its Course on International Justice,” Interview with Beth van Schaack, Justice Info, January 19, 2021, https://www.justiceinfo.net/en/68467-how-bidens-america-can-reverse-its-course-on-international-justice.html (accessed May 19, 2021); Christopher “Kip” Hale, “U.S.-ICC Relations Under a Biden Administration: Room to Be Bold,” Just Security (blog), January 22, 2021, https://www.justsecurity.org/74302/u-s-icc-relations-under-a-biden-administration-room-to-be-bold/ (accessed May 19, 2021).

[35] American Servicemembers’ Protection Act, 22 U.S.C. §§7421–7433 https://uscode.house.gov/view.

xhtml?path=/prelim@title22/chapter81&edition=prelim (accessed May 28, 2021).

[36] Joseph Biden, “Warner Amendment,” Congressional Record – Senate, June 6, 2002, https://www.congress.gov/crec/2002/06/06/CREC-2002-06-06-pt1-PgS5132.pdf (accessed May 28, 2021), p. S5145.

[37] See, for example, Foreign Relations Authorizations Act (FRAA), FY2000-01, Restriction of Funding on the ICC, §705(b), https://www.congress.gov/bill/106th-congress/house-bill/3427/text (accessed May 28, 2021).

[38] Steven Weisman, “U.S. Rethinks Its Cutoff of Military Aid to Latin American Nations,” New York Times, March 12, 2006, https://www.nytimes.com/2006/03/12/politics/us-rethinks-its-cutoff-of-military-aid-to-latin-american-nations.html (accessed June 8, 2021).

[39] Open Society Justice Initiative, International Crimes, Local Justice: A Handbook for Rule-of-Law Policymakers, Donors, and Implementers, 2011, https://www.justiceinitiative.org/uploads/4d978a66-7e25-4f40-a231-08388779c18c/international-crimes-local-justice-20111128.pdf (accessed May 28, 2021), pp. 177-182.

[40] Ned Price, US State Department Spokesperson, Twitter, @StateDeptSpox, “The fair and transparent selection of Guatemala’s Constitutional Court justices is critical for democracy. We value the U.S.-Guatemala partnership and support the fight against endemic corruption and impunity to help build a future Guatemalans deserve,” January 28, 2021, https://twitter.com/StateDeptSpox/status/1354928192683991046 (accessed May 19, 2021).

[41] International, Impartial, and Independent Mechanism to Assist in the Investigation and Prosecution of Persons Responsible for the Most Serious Crimes under International Law Committed in the Syrian Arab Republic since March 2011, https://iiim.un.org/ (accessed May 19, 2021); Independent Investigative Mechanism for Myanmar, https://iimm.un.org/ (accessed May 19, 2021).

[42] “Atrocities in Ethiopia’s Tigray Region,” US Department of State press statement, February 27, 2021, https://www.state.gov/atrocities-in-ethiopias-tigray-region/ (accessed June 15, 2021).

[43]“Press Statement on the official launch of the Commission of Inquiry on the Tigray Region in the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia,” African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights, June 15, 2021, https://www.achpr.org/pressrelease/detail?id=583#:~:text=The%20Commission%20of%20Inquiry%20was,virtually%20on%207%20May%202021 (accessed June 15, 2021).

[44] See Catherine Gonzales, “US Congress Bill Seeks to Halt Assistance to PH Police, Military,” Inquirer, September 24, 2020, https://globalnation.inquirer.net/191153/fwd-bill-seeking-to-halt-assistance-to-ph-police-military-introduced-to-us-congress (accessed May 19, 2021).

[45] “Promotion reconciliation, accountability and human rights in Sri Lanka,” Report of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Advance unedited version, January 27, 2021, https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Countries/LK/Sri_LankaReportJan2021.docx (accessed June 3, 2021), para. 59; “Sri Lanka on alarming path towards recurrence of grave human rights violations – UN report,” United Nations, Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights press release, January 27, 2021, https://www.ohchr.

org/en/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=26695&LangID=E (accessed June 3, 2021).

[46] See Human Rights Watch, Universal Jurisdiction in Europe: The State of the Art, June 27, 2006, https://www.hrw.org/report/2006/06/27/universal-jurisdiction-europe/state-art; “Europe: National Courts Extend Reach of Justice,” Human Rights Watch news release, September 16, 2014, https://www.hrw.org/news/2014/09/16/europe-national-courts-extend-reach-justice; Human Rights Watch, “Basic Facts on Universal Jurisdiction,” October 19, 2009, https://www.hrw.org/news/2009/10/19/basic-facts-universal-jurisdiction.

[47] 18 U.S.C. §1091, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2011-title18/pdf/USCODE-2011-title18-partI-chap50A-sec1091.pdf (accessed June 14, 2021); 18 U.S.C. §2441, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2015-title18/pdf/USCODE-2015-title18-partI-chap118-sec2441.pdf (accessed June 14, 2021); 18 U.S.C. §2340A, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2011-title18/pdf/USCODE-2011-title18-partI-chap113C-sec2340A.pdf (accessed June 14, 2021); 18 U.S.C. §2442, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2015-title18/pdf/USCODE-2015-title18-partI-chap118-sec2442.pdf (accessed June 14, 2021).

[48] 18 U.S.C. §1425 and §1426, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2010-title18/pdf/USCODE-2010-title18-partI-chap69-sec1425.pdf (accessed June 14, 2021); 18 U.S.C. §§1544-1581, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2015-title18/pdf/USCODE-2015-title18-partI-chap75-sec1546.pdf (accessed June 14, 2021).

[49] “Gambia: US Charges Alleged ‘Death Squad’ Member with Torture,” Human Rights Watch news release, June 12, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/06/12/gambia-us-charges-alleged-death-squad-member-torture.

[50] See Beth van Schaack, “Crimes Against Humanity: Repairing Title 18’s Blind Spots,” Stanford Public Law Working Paper No. 2705094, December 19, 2015, https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2705094 (accessed May 19, 2021).

[51] Draft articles on Prevention and Punishment of Crimes Against Humanity, International Law Commission, 2019, https://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/english/draft_articles/7_7_2019.pdf (accessed June 4, 2021).

[52] Leila N. Sadat and Madaline George, “An Analysis of State Reactions to the ILC’s Work on Crimes Against Humanity: A Pattern of Growing Support,” African Journal of International Criminal Justice (Fall 2020), https://ssrn.com/abstract=3684796 (accessed May 20, 2021), p. 25.

[53] See Mutual Legal Assistance Initiative, https://www.gov.si/en/registries/projects/mla-initiative/ (accessed June 4, 2021).

[54] “About Us,” US Department of State, Office of Global Criminal Justice, https://www.state.gov/about-us-office-of-global-criminal-justice/ (accessed May 20, 2021).

[55] Beth Van Schaack, “State Dept. Office of Global Criminal Justice on the Chopping Block–Time to Save It,” Just Security (blog), July 17, 2017, https://www.justsecurity.org/43213/u-s-office-global-criminal-justice-chopping-block/ (accessed May 20, 2021).

[56] Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021, Public Law No: 116-260, §7065(a)(2), https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/133/text (accessed May 20, 2021).

[57] Elie Wiesel Genocide and Atrocities Prevention Act of 2018, US Congress, Public Law No: 115-441, https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/senate-bill/1158/text (accessed June 9, 2021).

[58] See “The Global Fragility Act: A New U.S. Approach,” The United States Institute of Peace, January 15, 2020, https://www.usip.org/publications/2020/01/global-fragility-act-new-us-approach (accessed May 20, 2021).

[59] “Prevention and Protection Working Group,” Friends Committee on National Legislation, https://www.fcnl.org/issues/peacebuilding/prevention-and-protection (accessed May 20, 2021).

[60] US State Department, Bureau of Conflict and Stabilization Operations, “2020 Report to Congress Pursuant to Section 5 of the Elie Wiesel Genocide and Atrocities Prevention Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-441),” August 7, 2020, https://www.state.gov/2020-Report-to-Congress-Pursuant-to-Section-5-of-the-Elie-Wiesel-Genocide-and-Atrocities-Prevention-Act-of-2018 (accessed May 20, 2021).

[61] Beth Van Schaack, “Good Governance Paper No. 13: Atrocities Prevention and Response,” Just Security (blog), October 29, 2020, https://www.justsecurity.org/73141/good-governance-paper-no-13-atrocities-prevention-and-response/ (accessed May 20, 2021).