(Nairobi) – All warring parties in Tigray have been implicated in the attacking, pillaging, and occupying of schools since the conflict started, Human Rights Watch said today.

On just one example, government forces used the historic Atse Yohannes preparatory school in the regional capital, Mekelle, as a barracks after taking control of the city from the region’s former ruling party, the Tigray People’s Liberation Front, in late November 2020, and continued to use the school through mid-April 2021. Recent government efforts to reopen schools have partly been hindered by continuing insecurity, damage to schools, and protection concerns for students and teachers.

“The fighting in Tigray is depriving many children of an education and the warring factions are only making matters worse,” said Laetitia Bader, Horn of Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “Occupying and damaging schools ends up affecting the lives of Tigray’s future generations, adding to the losses that communities in Tigray have faced for the last six months.”

Human Rights Watch conducted telephone interviews between January and May with 15 residents, teachers, parents, former students, and aid workers about the situation facing Tigray’s schools, and assessed reporting by media outlets, aid agencies, and national human rights institutions. Human Rights Watch also reviewed satellite imagery that confirmed the presence of military vehicles inside the compound of Atse Yohannes high school in December and March, as well as videos and photographs showing damage to school property.

Several Mekelle residents said that in early December, Ethiopian forces began using the Atse Yohannes school as a base. After occupying the school for several weeks, they left; trucking away computers, plasma screens, and food. Interim authorities soon began to repair the damage so that classes could resume, but soldiers returned in February and occupied the school for another three months.

During this time, troops posted armed sentries at the school gate and built fortifications using stones around the school grounds. A Mekelle resident working near the school witnessed women enter and leave the school’s guarded compound on several occasions. “I saw different women taken inside. Sometimes they would stay two, three, or five days, and we would see them go in and out of the school,” she said. “They appeared beaten and were crying as they would leave… No one could ask the women what happened to them, and the atmosphere made it difficult to do so.”

Human Rights Watch was unable to confirm whether the soldiers sexually exploited or otherwise abused the women, but during the conflict there have been widespread reports of sexual violence by Ethiopian and Eritrean forces, including in Mekelle.

After Ethiopian forces suddenly left the school in April, Mekelle residents found widespread damage to classrooms and offices, and destruction of electrical installations, water pipes, and other property. Videos posted on social media and photos sent to Human Rights Watch corroborated their accounts. In April, Tigray’s interim government presented aid groups with a list of damaged and pillaged property at the school, from pens and student records to 288 burned chairs and three destroyed science labs.

“I have given my life and service to the school,” one teacher said. “There is now nothing left to try and begin again, to resume classes. The school won’t be functional even for next year, because of the damage. Everything was taken.”

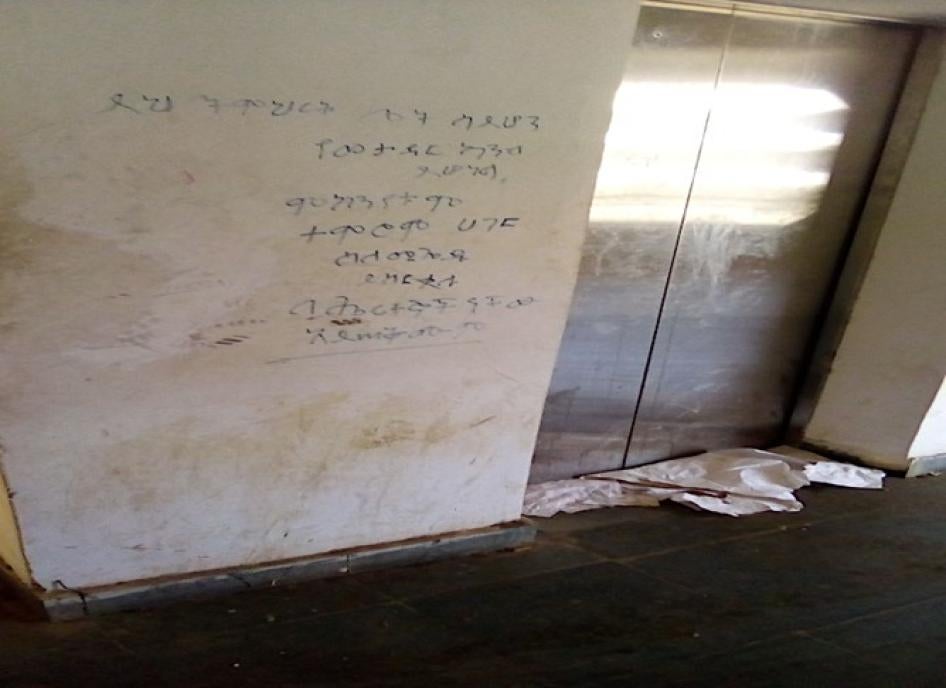

Ethiopian soldiers also left behind walls covered with hateful and vulgar anti-Tigrayan messages. “On the walls were phrases insulting Tigrayan people,” said one parent. “It was painful to see and read, let alone repeat again.”

Government authorities are now trying to reopen schools in Tigray, where an estimated 25 percent of schools have been damaged. In western Tigray, fighting displaced many teachers and left shortages of learning materials. The Education Ministry estimated that 48,500 teachers are in need of psychosocial and mental health support, and that some teachers at private schools are struggling to feed their families due to unpaid salaries.

Under the laws of war applicable to the armed conflict in Tigray, the occupation of a school by military forces makes the school subject to attack. The military’s destruction or seizure of civilian property not justified by reasons of military necessity is prohibited and may be a war crime. An extended military deployment without providing alternative educational facilities can also deny students their right to education under international human rights law.

The African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child has called on African countries to “either ban the use of schools for military purposes, or, at a minimum, enact concrete measures to deter the use of schools for military purposes.”

The African Union Peace and Security Council has urged all African countries to endorse the Safe Schools Declaration, an international political commitment – currently supported by 108 countries – to take concrete measures to better protect students, teachers, schools, and universities from attack during conflict, including by refraining from using schools for military purposes.

The Ethiopian government should endorse the declaration and incorporate the declaration’s standards in domestic policy, military operational frameworks, and legislation, Human Rights Watch said. Forces affiliated or allied with the Tigray People’s Liberation Front should also refrain from using schools as barracks or to store weapons. For schools that are housing internally displaced persons or need repair, the authorities should consult with communities and assess their needs and priorities, including protection concerns before pushing for schools to reopen, and request assistance from the United Nations and aid agencies to ensure that students deprived of education are provided safe and suitable alternative facilities.

“The conflict in Tigray has taken a terrible toll on children and their education,” Bader said. “International partners should now urge the Ethiopian government to take all necessary steps to ensure schools can reopen safely, including by ending the military use of schools and punishing military personnel responsible for abuses.”

For background information and further accounts of the Tigray conflict, please see below.

Attacks and Military Use of Schools during Tigray Conflict

Following a prolonged disruption in education due to the Covid-19 pandemic, schools in Tigray briefly reopened, only to shut down again after the outbreak of fighting in early November. Since then, warring parties have attacked, looted, or used schools as military bases across the Tigray region, leaving some unusable for educational purposes.

Attacks on schools in Tigray ranged from indiscriminate shelling to pillage and destruction. Human Rights Watch documented the unlawful shelling by Ethiopian forces of urban areas in Tigray, which struck near schools during military operations in November. Similarly, according to Doctors Without Borders (MSF), the Tsegaye Berhe secondary school in Adwa – which once accommodated over 1,200 students, but now houses families and communities displaced by violence – was hit by rockets early in the conflict, leaving at least two classrooms “littered with the smashed remains of computers, monitors, chairs, and books,” and the roof of the building exposed.

In January, satellite imagery revealed extensive damage to UN and humanitarian facilities, including a school and a clinic at two refugee camps hosting Eritrean refugees in Tigray.

According to Human Rights Watch’s research, armed forces pillaged food and school materials in at least three schools and a university in Tigray. Several residents said that Eritrean troops looted food and materials reserved for students at Axum University after Eritrean forces massacred civilians in the town. Eritrean refugees at Hitsats camp witnessed Eritrean forces loot offices and education facilities in mid-November.

Throughout the conflict, all parties have used schools as military bases. Residents in Axum described the occupation of Basen primary school by Eritrean forces, who used it as a camp after Ethiopian and Eritrean forces took control of the town in mid-November. In the farming village of Bissober, in southern Tigray, Tigrayan armed groups occupied the local elementary school before the conflict began and remained for several months, digging trenches around the school, and storing weapons in the principal’s office, according to media reports. Ethiopia’s National Human Rights Commission also described the school as partially damaged by heavy artillery after clashes between Tigrayan fighters and Ethiopian soldiers.

Tigrayan forces also occupied a secondary school outside of Shimelba refugee camp – satellite images show that the ground around the secondary school had burned down before fighting broke out near the camp between Tigrayan and Eritrean forces in December, according to refugee accounts.

While the Education Bureau appears to collect some data to track military use and damage of schools, the authorities were only able to conduct assessments in larger towns to which they had access, but not those occupied by Eritrean and Amhara forces. Although it is likely an underestimate due to limited access, the authorities in May had determined that 15 schools in the region had been significantly damaged in Tigray, while 53 others had some damage, and 2 primary schools in southern Tigray remained under occupation by Ethiopian forces.

The military occupation and attacks on schools have taken place in the context of mounting reports of laws-of-war violations, including apparent war crimes. These involve unlawful shelling, widespread pillage, destruction of crops and infrastructure, extrajudicial killings and large-scale massacres targeting young men and boys, sexual violence, and forced displacement. More than 60,000 refugees have fled to neighboring Sudan.

Over a million Tigrayans are now internally displaced within the region, some hosted in makeshift shelters or by families; others have sheltered on university campuses and in schools, including those damaged by artillery fire or from looting during the early phases of the conflict.

Even prior to the Tigray conflict, the Ethiopian government had failed to adequately protect schools from attack and occupation. In 2012, Ethiopian military forces used a school in Chobo-Mender, Gambella region as a prison. During the 2015-2016 Oromo protests, federal defense forces occupied schools and university campuses, where they harassed, beat, and arrested students. In 2007, Human Rights Watch documented that Ethiopian forces in Somalia carried out indiscriminate attacks from a base inside the Mohamoud Ahmed Ali Secondary School in Mogadishu.

Military Use and Pillage at Atse Yohannes Preparatory School

Atse Yohannes preparatory school is a public school that sits on a main road in Tigray’s regional capital, Mekelle, near government offices, including the police commission and the education bureau. The school was built over 60 years ago and recently renovated through alumni donations and support from organizations. It had approximately 2,000 students and 150 staff.

After taking control of Mekelle in late November, Ethiopian soldiers began occupying the school and prevented staff and local residents from entering the grounds. “It was difficult … to observe what [the soldiers] were doing in the school,” said one resident. “We saw when they were leaving, or when they sat with the coffee and tea sellers across the road. When they left the school, they were carrying different property with them on trucks that passed by our homes.”

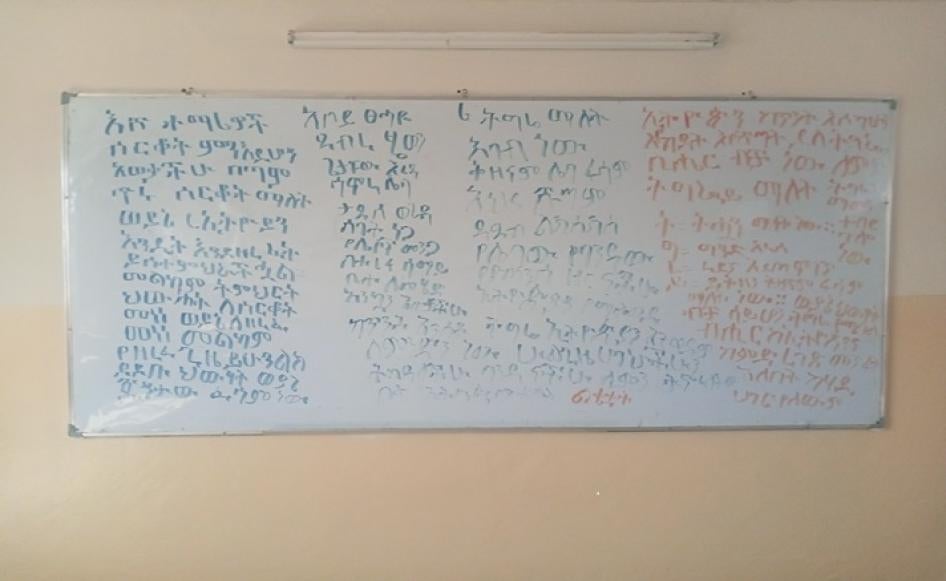

Administrators and residents assessed the pillaged property after the soldiers evacuated the school in January and wrote letters to the Education Bureau outlining losses and damage. As preparations began for classes to resume, a second contingent of soldiers arrived in February, forcing local officials and administrators to leave.

“They brought different army equipment,” said one staff member. “They built a fort, inside and outside of the school, it looked like a war zone.” Soldiers fortified parts of the school with stones, sandbags, and material from collapsed old buildings. Residents said they also placed weapons on the roof of the school building. “They used the school to control and patrol the town,” said one man.

Even though the Ethiopian military’s northern command headquarters is based in Mekelle, three to five kilometers away, a Tigray interim official said that the city did not have a functioning police system, so the federal forces justified the use of the school as “they needed a camp nearby to deploy and respond quickly… So the [military] would just come and go…We can’t guarantee that the forces won’t come back.”

After the military vacated the school in mid-April, they left uniforms in classrooms and metal ties used to bind hands. One parent said: “We found blood on the floors and livestock parts in the school. Maybe they were butchering animals in the school. And they had also burned and destroyed student documents.” Signs of fortifications, including stones and sandbags, were also visible, creating the risk that the school may be identified as a military target.

Parents, teachers, residents, and officials began to assess the damage and provided a long list of property looted and damaged during the total occupation of the school. “After the second round, we made an inventory too, but everything was destroyed, from electric installations, the toilets, the elevators, everything,” a teacher said. “The buildings are just left standing.”

Several Mekelle residents and officials said that what was most striking and painful was the hateful slogans written in Amharic on the school walls. One person explained the graffiti:

It was insulting to Tigray and its people: “Tigray and snakes are the same”; “Tigray must be cleansed”; “Tigray must be cleansed for the development of the country”; “insults about junta, Tigray are junta.” There were a lot of different things that were written about Tigray women that I cannot repeat. It is too painful.

Many experienced trauma and financial loss, underscoring that the harmful consequences of military use and attacks on schools go beyond the immediate impact of the closures.

“When they left the school, everyone was happy and relieved. They stayed for several months, and they terrified us,” one man living near the school said.

Concerns about Reopening Schools in Tigray

As administrators prepare for schools in Tigray to reopen, professionals and parents have expressed protection concerns. “There is no security in Mekelle because there is war around Mekelle and in Tigray,” said one teacher. “They want to reopen the school to be able to say Tigray is in peace, that everything is ok, that there is no war. But that is for propaganda purposes Even now, I don’t even have a guarantee to go home safely at night.”

Interim authorities admit that there are ongoing security challenges, including the need to provide psychosocial services to address the community’s trauma. “We’ve been talking to communities, teachers, trying to convince them to return to school,” said one official. “But even families in Mekelle don’t want to send their children back.”

The ongoing threats and intimidation by armed forces, as well as reports of sexual violence, shootings, and arrests were the reasons parents and others frequently cited for not wanting to send their children to school. One teacher said:

I don’t feel comfortable. There is no security. The students can’t come to the school. I am crying … sad, desperate. I am not happy to reopen the school. They [the forces] can come back again at any point.

For many parents and residents, however, the protection concerns stem from fear of abusive Ethiopian government forces. A parent said:

The soldiers must withdraw. They are raping women, killing people. So even if the schools reopen, it is hard to send our children to school if they are still raping women and girls and killing people. The international community needs to help, for our children’s sake.

Protecting Schools from Military Use in Africa

Under Ethiopia’s criminal code, during wartime the “the confiscation, destruction, removal, rendering useless or appropriation of property such as … schools” is a war crime.

Other countries on the African continent have more explicitly banned the use of schools for military purposes. For example, in 2020, the Central African Republic criminalized the occupation of schools on the same basis as an attack on a school, susceptible to 10 to 20 years in prison, and/or a fine of 5 to 20 million francs (US$9,000 to $37,000). In 2017, the Sudanese Armed Forces issued a command order prohibiting the military use of schools in areas of active conflict. In 2014, South Sudan’s army chief of staff issued an order reiterating a prohibition on occupying schools in any manner, subject to “the full range of disciplinary and administrative measures.”

In 2013, the Democratic Republic of Congo’s defense minister issued a ministerial directive providing for criminal and disciplinary sanctions for soldiers who requisition schools for military purposes. Currently, Nigeria – which will host the Fourth International Conference on the Safe Schools Declaration later in 2021 – is considering a proposed amendment to its Armed Forces Act that would state that “No premises or building or part thereof occupied for educational purposes or accommodation of persons connected with the management of school or vehicles and other facilities of educational institutions shall be requisitioned.”

Ethiopia is also one of the largest troop contributors to UN peacekeeping operations. Such troops are required to comply with the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations’ “UN Infantry Battalion Manual,” which includes the provision that “schools shall not be used by the military in their operations.” In January, the African Union adopted a new doctrine requiring troop contributors to its peace operations to “ensure that schools are not attacked and used for military purposes.”