Available in Français

Summary

When armed men on motorcycles tore up to a school in Béléhédé village in Burkina Faso’s Sahel region in early 2018, panic ensued. “I was in class when the terrorists came. ... They fired a shot, and we all fled to save ourselves,” said Boureima S. (not his real name), a 14-year-old student at the time. “Afterwards, when we went back there, I saw they had burned the principal’s motorcycle... the [school’s] office... and the students’ notebooks.”

Boureima’s school closed following the attack in 2018 and never reopened. When Human Rights Watch spoke with him in February 2020, he had not yet stepped back inside a classroom. Like hundreds of thousands of students in Burkina Faso, Boureima’s education was cut short by the country’s steadily worsening armed conflict.

Since the first recorded attacks on Burkinabè schools in 2017, the number and severity of such attacks have surged. Armed Islamist groups allied with Al Qaeda or the Islamic State have burned, looted, and destroyed scores of schools. “It’s their war against education,” one teacher said.

The armed groups have also intimidated students, terrorized parents into keeping their children out of school, and killed, abducted, brutalized, or threatened scores of teachers. In many cases, the assailants committed the abuses directly in front of terrified students, leaving both teachers and children physically or mentally scarred.

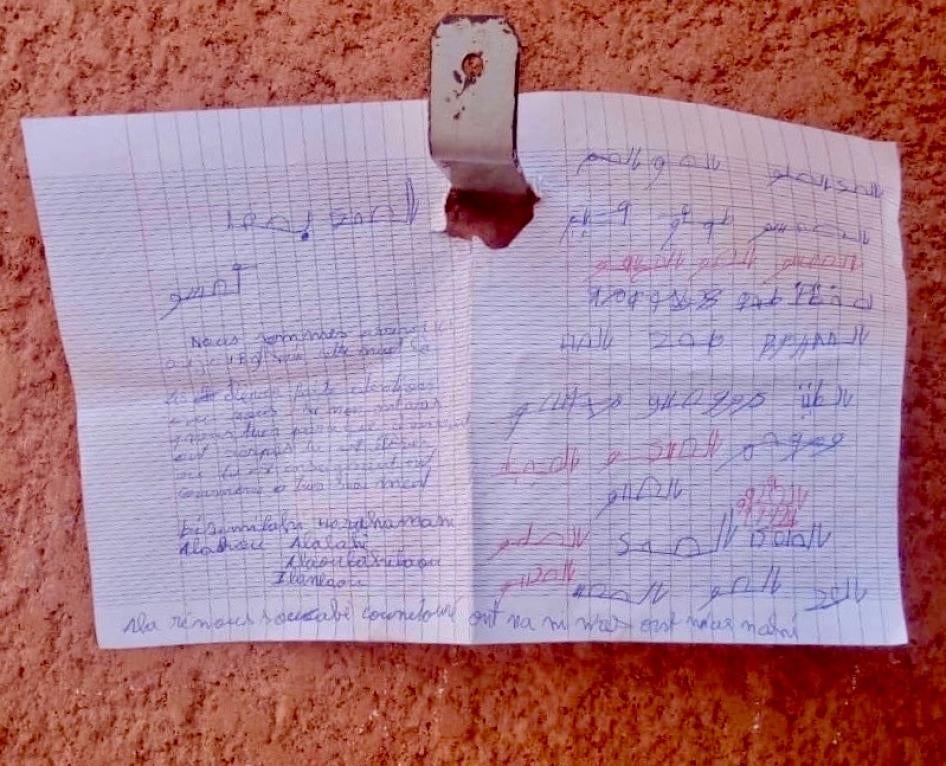

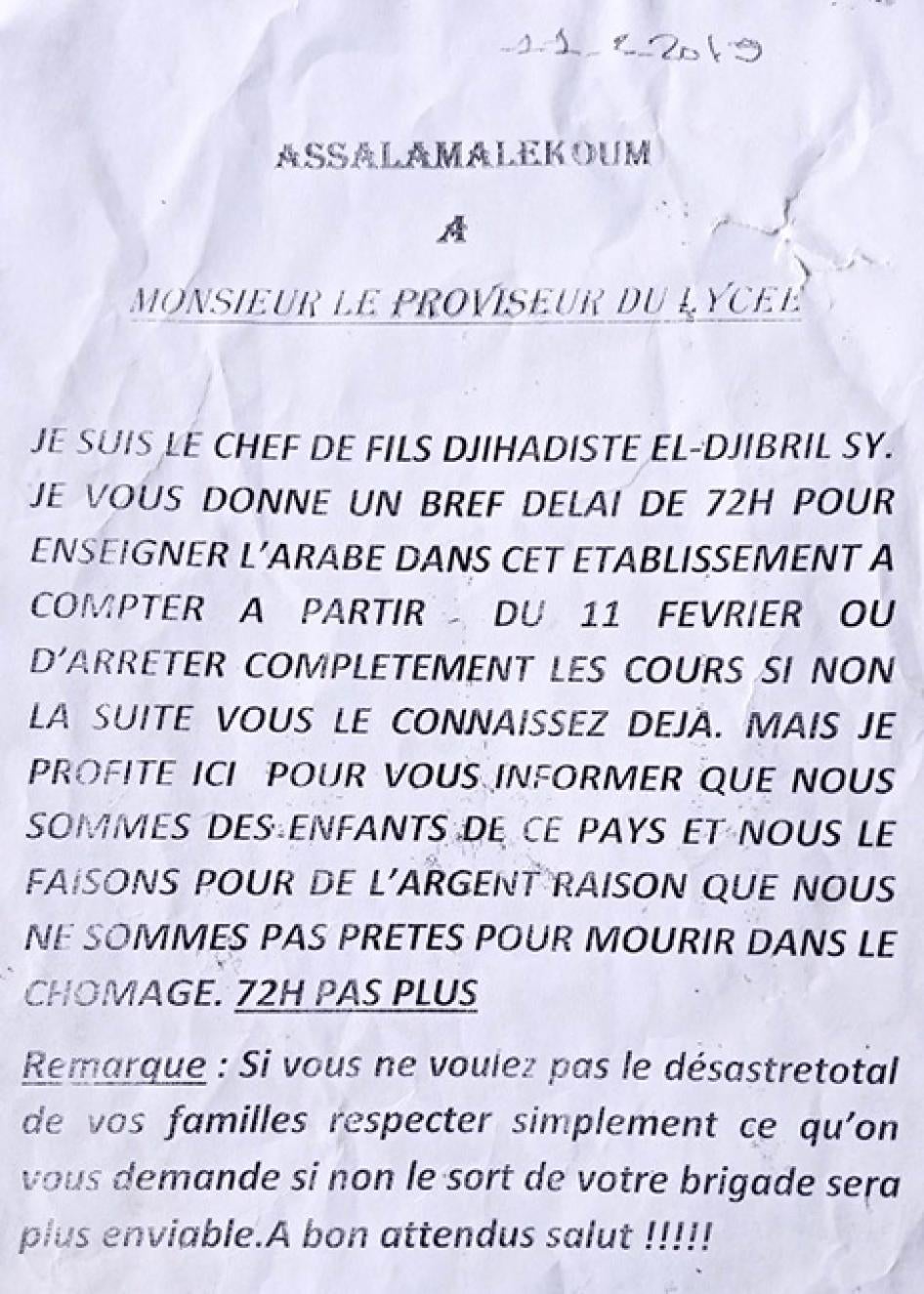

While armed Islamist groups officially claimed only a few attacks, assailants typically justified their attacks by citing their opposition to “French” education, insisting that children should study only Arabic and the Quran, or not study at all.

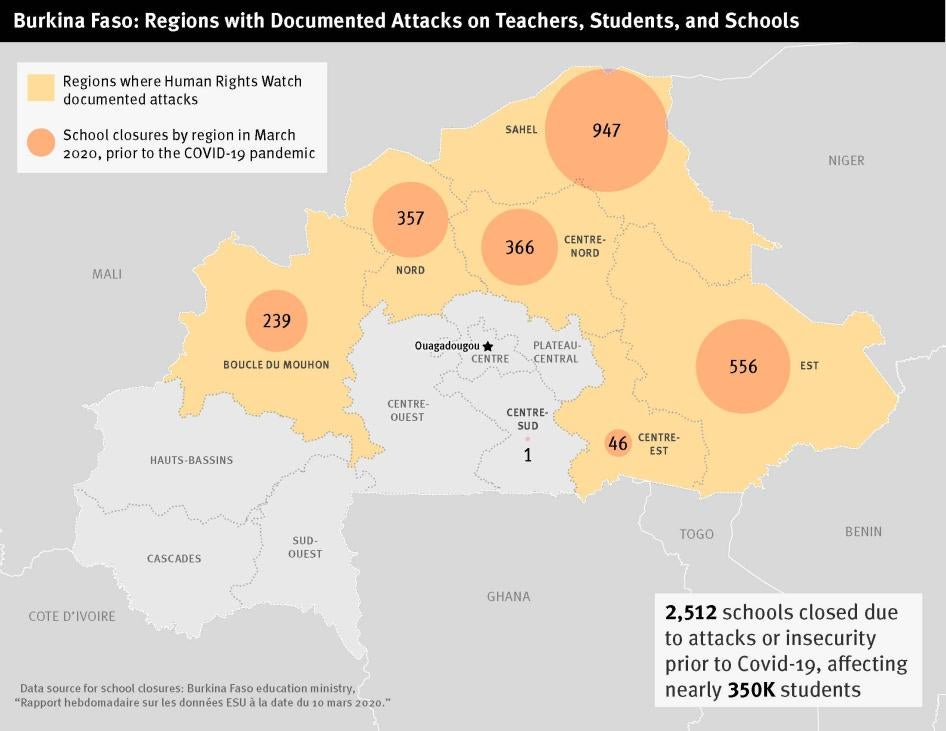

These attacks, the terror they generated, and worsening insecurity have resulted in a cascade of school closures across the country, undermining students’ right to education. By early March 2020, the Ministry of National Education, Literacy, and the Promotion of National Languages (“education ministry,” or MENAPLN) reported that over 2,500 schools had closed due to attacks or insecurity in Burkina Faso, negatively affecting almost 350,000 students and over 11,200 teachers. This was prior to the country’s Covid-19 outbreak, which resulted in the temporary closure of all schools from mid-March.

Based on Human Rights Watch interviews with 177 people—including 74 teachers and school administrators, 35 current and former students, 12 parents, and other witnesses to attacks, relatives of victims, community leaders, experts, aid workers, and officials—this report documents attacks on students, education professionals, and schools allegedly carried out by armed Islamist groups in six regions of Burkina Faso between 2017 and 2020.

Burkina Faso has been grappling with armed Islamist insurgent groups since the emergence in 2016 of Ansaroul Islam, a homegrown group with roots in the country’s northern Sahel administrative region. Ansaroul Islam and a patchwork of groups linked to Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) regularly attack civilians and civilian objects as well as military targets. These attacks have reportedly caused more than 1,800 deaths.

In 2019, there was a spike in abuses by these groups, including attacks on teachers, students, and schools. In response, the Burkinabè security forces carried out counterterrorism operations that resulted in numerous human rights violations, including the killing of civilians. From January 2019 to April 2020, the number of people displaced from their communities by the conflict skyrocketed from 87,000 to over 830,000, according to the United Nations. Hundreds of teachers were among those who fled.

The bulk of the attacks on teachers, students, and schools occurred in 5 of the country’s 13 administrative regions: Sahel, Nord, Centre-Nord, Est, and Boucle du Mouhoun. However, the most egregious attack to date—the execution of five teachers in a school in April 2019—took place in Centre-Est region. Though Ansaroul Islam and ISGS claimed a small number of the education-related attacks, most went unclaimed.

Documented Attacks and Abuses

Human Rights Watch documented 126 attacks on students, education professionals, and schools occurring between 2017 and 2020. Threatening raids by armed men ordering school closures or teacher departures (28 cases) have been included in the totals. Many additional attacks were reported in the media and elsewhere, suggesting the total number of attacks during this period is likely much higher.

The documented cases include 107 attacks on or at schools, half of which took place in 2019. At least 12 of the attacks on schools involved violence against education workers, and students were present during at least 31 incursions. In 84 cases, attackers damaged, destroyed, or pillaged school infrastructure, materials or supplies. (For a breakdown of all documented attacks by year, region, and type, see Annex I.)

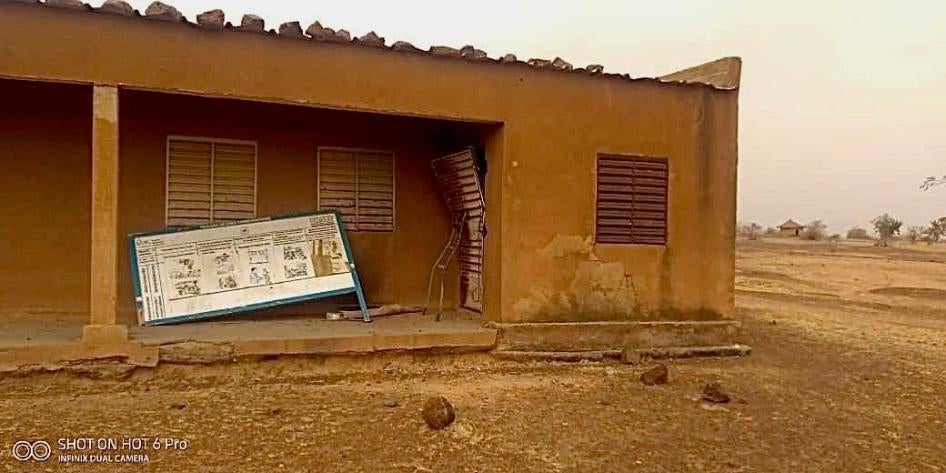

During attacks, armed men killed, beat, abducted, and threatened education workers; intimidated and threatened students; set classrooms, offices, and teachers’ residences on fire; shot at windows, doors, walls and roofs; set off explosives; burned school documents and academic materials; stole, damaged, or destroyed school employees’ property; and pillaged supplies from canteen warehouses and storerooms.

This report documents the targeted killings of 12 teachers and school administrators, as well as three school construction workers, between 2017 and March 2020. Twelve of these fifteen killings took place in 2019.

The report also documents dozens of other attacks on teachers, including assault and abduction. A parent who arrived at a school just after an attack described the horrors he witnessed: “At the school we found the fire still burning. We found the teachers there who had been beaten, some so severely that they couldn’t speak... They were in shock.” One of the teachers said, “Some students... were there watching when they beat us... They were crying.” In another case, a teacher who was abducted, robbed, and threatened said: “They tied my arms, covered my face, and took me away by motorcycle. ... I was so afraid.”

In May 2020, the education ministry reported that 222 education workers had been “victims of terrorist attacks” as of late April.

While children were not targeted for violence during the attacks on schools, at least one child was killed and one injured by stray bullets during attacks at or near schools. Students have also been killed in other attacks on civilians, including seven students returning from school break who were killed in January 2020 when an explosive device detonated under their public transport bus. “I saw my classmates dead,” said one student. Another said he lost a friend in the attack: “It has affected me to the point that I can’t sleep... I’ve continued school, but sometimes I’m following a lesson and I get lost.”

Students have also been threatened and harassed by armed Islamists to stop attending school. Human Rights Watch documented three cases in which students were forced to watch as insurgents destroyed their notebooks. A 16-year-old student recounted: “The jihadists... grabbed our backpacks and took out the notebooks, and they said, ‘Watch closely!’ Then they burned our notebooks.”

Military Use of Schools

Human Rights Watch documented the alleged use of 10 schools by members of the Burkinabè armed forces, the Defense and Security Forces (Forces de Défense et de Sécurité, FDS), for military purposes in Centre-Nord and Sahel regions in 2019, including three occupied as bases for six months to a year. In at least eight cases, the schools had reportedly closed due to insecurity prior to the occupation. For one case, there were conflicting accounts regarding the timeline of the military’s arrival and the school’s closure.

The use of schools for military purposes puts important education infrastructure at risk of damage and destruction in the event of an attack on the soldiers deployed at the school. At least four schools in Burkina Faso were attacked during or directly after the military’s occupation of the schools.

Additionally, presumed armed Islamists carried out the execution of a villager at a school in Sahel region in 2018, and they allegedly occupied at least five schools for short daytime or overnight stays in Centre-Nord region in 2019.

Negative Consequences for Students, Teachers, Society

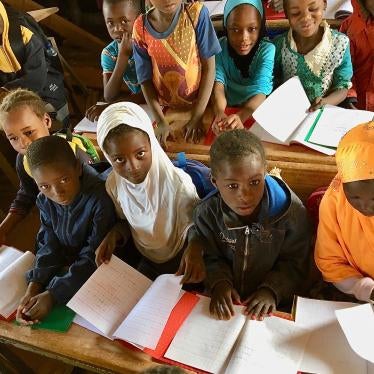

Burkina Faso already faced major challenges to ensuring education for all children, due to factors such as poverty, poor school infrastructure, poor access, low completion rates, and insufficient numbers of trained teachers, particularly in rural areas. Additional barriers for girls included gender bias, high levels of child marriage, and sexual violence and harassment in and en route to school. The education-related attacks and general insecurity—along with the Covid-19 pandemic—have exacerbated those challenges, reversing decades of progress in increasing school attendance.

Attacks on schools and class disruptions have reduced the quality of education students receive and put many students behind in their studies. One student said that she had failed her final exam after an attack forced her school to close for weeks, leaving her unable to prepare. Another said, “It makes me unhappy, to not be able to finish, to have to retake classes, to not even have any documents to show you took the class. ... You can’t even be sure you will continue your studies.”

Attacks have caused extensive fear-induced withdrawals from schools, as well as long-term psychosocial consequences for students. “Many students don’t even want to look at a school again,” said one teacher. “The attack [on my school] really disturbed me... I don’t have the spirit to go back to school,” said a former student.

Other students, despite the countless barriers in their way, are determined to return to school. “I want to go to school because it’s good,” said a 15-year-old girl who had been out of school for an entire academic year. “I want to be a teacher.”

In their desperation to continue classes, many children affected by school closures enrolled in schools in towns away from home. Some began commuting long distances, exposed to risks on the road. Others moved to towns to live in groups of children, without an adult family member, putting them at risk of exploitation and violence. These children often live in squalid conditions, struggling to pay for food and school fees.

This report also documents cases of child labor resulting from school closures, including out-of-school children working in the markets, as domestic help, in gold mines, and making bricks. It also explores how girls may be less likely to be re-enrolled in school than boys and face increased risks of child marriage when out of school.

Teachers have also suffered devastating consequences as a result of attacks, including trauma, physical problems, and loss of everything they owned. “[They] set a fire in my house. ... I found everything charred—there was nothing left,” said one teacher. “I get migraines... my head and entire body hurts,” said another. At least two pregnant teachers experienced miscarriages following attacks on schools.

Attacks on education can have an incalculable long-term effect on society. “Large numbers of children will miss out on the education necessary for their cognitive and social-emotional development, which will make them vulnerable to armed terrorist groups. That’s what the terrorists want—children to be ignorant, so they can influence them and put whatever they want in their heads,” said Jacob Yarabatioula, a Burkinabè researcher specializing in terrorism. “We all should fear this.”

Legal Protections

During an armed conflict such as is occurring in Burkina Faso, international humanitarian law, or the laws of war, apply to both national armed forces and non-state armed groups. Deliberate or indiscriminate attacks on civilians including teachers and students, as well as on civilian objects such as schools, are violations of the laws of war. Individuals who ordered or were involved in such attacks, including summary executions, torture and other ill-treatment, arbitrary detention, and looting, are responsible for war crimes.

Attacks on schools may also deprive students of their right to education, protected under international human rights law, notably the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

In 2017, Burkina Faso endorsed the Safe Schools Declaration, a political agreement committing countries to a range of measures aimed at strengthening prevention and response related to attacks on students, teachers, and schools. By doing so, Burkina Faso committed to using the Guidelines for Protecting Schools and Universities from Military Use during Armed Conflict, which urge parties to armed conflicts not to use schools—and particularly not functioning schools—“for any purpose in support of the military effort.”

Responses and Needs

The Burkinabè government has taken important steps to implement measures in line with the Safe Schools Declaration. These initiatives, notably those aimed at ensuring continued access to education, included creating a national strategy and technical secretariat on “education in emergencies,” redeploying teachers, working to reopen schools, organizing catch-up sessions for students, and instructing schools to enroll displaced students “systematically and without fees.”

Though the international humanitarian response plan in Burkina Faso remains underfunded, aid agencies have provided crucial support to government efforts and partnered on several initiatives, such as setting up temporary learning spaces.

This report identifies several gaps and needs in the response efforts to date, including the insufficient resources, personnel, and infrastructure devoted to schools enrolling displaced students. “The schools are saturated!” said a local official in Centre-Nord region prior to the Covid-19 closures. “One class can have up to 150 students,” a teacher reported.

Another problem is the lack of psychosocial support to teachers and students who experienced education-related attacks, as well as delayed or nonexistent government compensation to teachers who lost property in attacks by armed groups. “The attack hurt me very much, but the fact that after the attack, we weren’t supported... that’s what still bothers me,” said one teacher.

Other issues include the lack of adequate security for many schools operating in at-risk regions, as well as the government’s failure to regularly collect and share sufficient data on education-related attacks and military occupation of schools, which can hinder response efforts.

The Burkinabè government should immediately address these issues, and its humanitarian and international partners should consider increasing their support to meet the identified needs. Authorities should pay attention to the ways in which school closures differently impact boys and girls, and should address the particular challenges to education for girls.

The government should also take concrete measures to deter the use of schools for military purposes, drawing upon examples of good practice by other African Union countries, and at a minimum implementing the Guidelines on Protecting Schools and Universities from Military Use during Armed Conflict.

Armed Islamist groups should cease all attacks on teachers and schools, extrajudicial killings, abductions, and other serious laws-of-war violations and human rights abuses.

Students, parents, and teachers have suffered immensely as a result of attacks on education in Burkina Faso. Education has become one of the greatest casualties of the conflict, crushing the hopes of hundreds of thousands of children for a better future.

During times of insecurity, maintaining access to education is vital. If children remain in safe and protective environments, schools can provide an important sense of normalcy essential to children’s development and psychological well-being.It is crucial that a generation of children in Burkina Faso do not lose access to education.

Recommendations

To the Burkinabè Government

- During the period in which schools remain closed as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, prioritize and expand efforts to continue education for all children through available distance-learning programs, including educational radio and television programming and online education resources, as well as contextually-tailored approaches for localities with limited access to these technologies.

- When schools are reopened nationally after Covid-19 lockdowns are lifted, ensure that all children regain access to education. In particular:

- Ensure that students deprived of access to education as a result of armed conflict are promptly given access to accessible alternative schools.

- In areas where children are unable to enroll in schools, ensure the provision of alternative learning opportunities such as community education, distance learning, and temporary learning spaces.

- Ensure that any post-Covid-19 “back-to-school” campaigns and remedial classes are inclusive of children who previously stopped studies due to attacks on schools, insecurity, or displacement; and continue and expand distance-learning programs established in response to Covid-19 to benefit these children.

- Encourage parents who had withdrawn their children from school due to fear of attack to re-enroll them, or to make use of distance learning programs or temporary learning spaces.

- Consider implementing special education outreach programs for displaced children who have never attended school, including those from nomadic Peuhl communities.

- Rebuild and re-equip damaged or destroyed schools as soon as possible.

- Increase support to overloaded “host schools” taking in large numbers of displaced students, with a view to expanding their capacity, including by constructing additional classrooms, deploying additional teachers, and providing more desks, materials, and canteen food supplies.

- Take greater measures to protect schools that are operating in high-risk areas, including by setting up prevention measures (risk mapping and early warning systems) and rapid reporting and response systems for attacks on schools. This should include setting up a hotline for teachers and parents to quickly report threats or attacks on schools to local security forces and education authorities.

- Take concrete measures—for example, through legislation, standing orders, and training—to deter the military use of schools, drawing upon examples of good practice by other African Union countries, and at a minimum implementing the Safe Schools Declaration and the Guidelines on Protecting Schools and Universities from Military Use During Armed Conflict.

- Develop and expand the work and capacity of the Technical Secretariat for Education in Emergencies.

- Consider permitting teachers to adopt alternate listings for their “profession” on their national identification cards, in order to decrease their risk of being targeted.

- Address barriers to girls’ education, including implementing nationwide programs to empower girls to attend school and ensuring that “education in emergencies” responses address the particular needs of pregnant girls and young mothers of school-going age.

To the Burkinabè Defense and Security Forces

- Take greater steps to ensure the protection and security of schools operating in high-security risk areas, including by increasing patrols, while minimizing activities that would turn schools into military targets.

- Vacate all schools being occupied as military bases where feasible alternatives exist, and where they do not, take steps to identify or create feasible alternatives. Increase logistics planning and supplies to minimize the need to use schools, and consider using temporary accommodations such as tents.

- Order commanding officers not to use the buildings or property of functioning schools for military purposes such as camps, barracks, or deployment. Draw upon examples of good practice by other African Union countries and implement the Guidelines for Protecting Schools and Universities from Military Use during Armed Conflict, which Burkina Faso committed to use by endorsing the Safe Schools Declaration in 2017.

- Incorporate protections for schools from military use in military doctrine, operational orders, trainings, and other means of dissemination to ensure compliance throughout the chain of command.

- Ensure that doctrine and trainings applicable to Burkinabè armed forces being deployed on United Nations peacekeeping missions reflect the requirement of the UN’s 2012 Infantry Battalion Manual that “schools shall not be used by the military in their operations.”

To the Ministry of Education

(Ministry of National Education, Literacy, and the Promotion of National Languages)

- Ensure availability and accessibility of schools, effectively implement the Safe Schools Declaration, and work with school authorities, community leaders and parents to ensure better security for schools in conflict-affected regions.

- Ensure that teachers and administrators are not pressured to reopen schools in insecure zones where there are credible threats to their safety, without appropriate security measures.

- Ensure that public schools follow the ministry’s instructions to eliminate school fees for displaced students.

- Designate a fund to support schools hosting displaced students, and ensure they have adequate personnel, infrastructure, and equipment.

- Extend temporary learning spaces (both temporary classrooms for formal schooling, and “child-friendly” spaces) and other “education in emergencies” programs to reach additional towns and sites hosting large numbers of displaced people, prioritizing those that have not yet benefitted from these programs.

- Provide timely compensation to education workers who suffered property loss or injury in targeted attacks, and take steps to share information and increase public communication regarding public school employees’ entitlements in this regard.

- Expand data collection efforts to include the following, disaggregated by gender:

- Attacks on students, teachers, and schools: date and location; type of school; victims and suspected perpetrators; number of students affected.

- Military use of schools: types and locations of schools being used; purpose and duration of use; the unit or group making use of the school; whether the school had ceased functioning prior to military occupation; student attendance prior, during, and after the period of use.

Support to Schools in Conflict-Affected Areas

- Take greater steps to ensure the protection of schools operating in high-risk areas, including by implementing protocols and a rapid reporting and response mechanism (with a hotline) for school attacks, in order to ensure that the relevant authorities are informed, and timely assistance provided.

- Extend training in risk mitigation and emergency response to cover all schools in at-risk areas and assist schools to develop individualized plans.

- Improve school infrastructure and construct walls or fences around schools as needed, in order to provide some measure of increased protection.

- Equip all schools, including those rebuilt or rehabilitated following attacks, with adequate facilities for menstrual hygiene management.

To the Ministries of Education and Humanitarian Action

(Ministry of National Education, Literacy, and the Promotion of National Languages; Ministry of Women, National Solidarity, Family, and Humanitarian Action)

Support to Victims and Witnesses of Attacks

- Ensure that all teachers and school administrators who are victims of attacks receive timely, appropriate, and subsidized medical and psychosocial support, and ensure that such support includes follow up.

- Dispatch appropriate medical and psychosocial experts to the victim’s location, or as near as possible, to ensure that victims are not required to travel long distances to obtain care. If victims are required to travel, ensure that transportation, lodging, and other expenses are covered.

- Inform all public-school teachers about how they can access free support services.

- Establish a system to follow up with students who have witnessed attacks in order to assess their psychological and emotional well-being, and provide counseling services or other treatment as necessary.

Reducing Negative Impacts on Children

- Develop and implement measures to remedy the disproportionate impact of school closures on girls, including by working to reduce child marriage and adopting measures to assist girls who have lost access to education.

- Follow up on reported cases of children living alone to continue their studies, to ensure these children are placed in the care of an adult family member or guardian.

- Implement programs to support out-of-school children and reduce child labor.

- Proceed with the establishment of Community Child Protection Units as soon as possible, and ensure that units are set up in displacement camps and sites.

To the Ministry of Justice

- Ensure impartial investigation and appropriate prosecution of members of armed Islamist groups implicated in unlawful attacks on students, teachers, and schools, and for other abuses of international human rights and humanitarian law.

To Armed Islamist Groups in Burkina Faso

- Cease all violations of the laws of war, including attacks on civilians and civilian structures related to education, such as the killing, abduction, assault, robbery, and intimidation of teachers, school administrators and students; and the looting, burning and damaging of schools.

- Cease human rights abuses against students and teachers, as well as threats undermining children’s right to education.

- Cease the indiscriminate use explosive devices, including on routes used by civilian vehicles.

- Refrain from using schools for military purposes.

To Burkina Faso’s International and Regional Partners

- Urge the Burkinabè government and military to adopt the above recommendations and support their implementation.

- Continue to support and consider expanding “education in emergencies” programs in Burkina Faso, notably to benefit still-unreached children affected by conflict-related school closures, as well as to build capacity among “host schools” accepting large numbers of displaced students.

- Support victim rehabilitation in Burkina Faso, including psychosocial care for teachers and students who experienced attacks.

To the United Nations

- The UN secretary-general should include Burkina Faso in his annual report on children and armed conflict to the UN Security Council, initially as a situation of concern, pending the establishment of a monitoring and reporting mechanism.

- Pending the establishment of a formal Monitoring and Reporting Mechanism on children and armed conflict, the UN country team should actively document and verify cases of grave violations against children, including attacks on students, teachers, and schools, and provide this information to the special representative to the secretary-general for children and armed conflict. The special representative should also actively request this information.

Methodology

The report is based on in-person interviews conducted in the cities of Ouagadougou and Kaya in Burkina Faso during four weeks between December 2019 and February 2020, as well as telephone interviews conducted between December 2019 and April 2020. The attacks documented took place between January 2017 and March 2020.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 177 people, including 74 education professionals, 35 current or former students, and 12 parents of students. The current and former students included 22 children (13 girls, 9 boys) ages 10-17, and 13 young adults (9 women, 4 men) ages 18-26. The remaining interviews were with witnesses to abuses, relatives of victims, civil society members, community leaders, humanitarian workers, UN officials, security analysts, education ministry officials, and local government officials.

Interviewees included current or former residents of seven regions: Boucle du Mouhoun, Centre, Centre-Est, Centre-Nord, Est, Nord, and Sahel.

Interviews were conducted in French, Mooré (spoken by ethnic Mossi), and Fulfulde (spoken ethnic Peuhl). Interviews in Mooré and Fulfulde were conducted with interpreters.

To maintain security for interviewees, all in-person interviews were conducted in or around Ouagadougou, the capital, and Kaya, a city in Centre-Nord region. Some individuals travelled to these cities for the interviews, while others were already there, having previously fled violence.

Nearly all survivors of attacks and witnesses to abuses by armed Islamist groups expressed extreme anxiety about their identities being revealed. Names and identifying information of many interviewees have therefore been withheld to protect their safety. All children’s names have been withheld or replaced by pseudonyms.

The Human Rights Watch researcher informed all interviewees of the nature and purpose of the research, and of Human Rights Watch’s intention to publish a report with the information gathered. The researcher obtained oral consent for each interview and gave each interviewee the opportunity to decline to answer questions. Interviewees did not receive material compensation for speaking with Human Rights Watch, however travel expenses incurred by interviewees were reimbursed.

On April 20, 2020, Human Rights Watch sent three letters to the Burkinabè government: one to the education ministry; one to the humanitarian action ministry; and one to the Burkinabè ambassador to the United States, requesting that the letter be transmitted to the prime minister and the ministries of defense, security, justice, and human rights. The letters presented our preliminary findings and included questions on the government’s responses to education-related attacks and the military use of schools.

On May 18, 2020, Human Rights Watch received two letters, one from the education ministry and one from the humanitarian action ministry, with detailed responses to our questions. Certain elements of these responses have been integrated into the report, and the letters are included as Annexes II and III.

Terminology

Students: A “student” may refer to a child (under age 18) or an adult (18 or older). In Burkina Faso, many students begin school late, or stop and restart, with the result that primary to secondary students can range from 6 to around 25 years old, or sometimes older.

Teachers: In Burkina Faso, all teachers are referred to as enseignants. Primary school teachers are also called instituteurs or maîtres; middle school and high school teachers are also called professeurs.

School principals: Directeurs for primary and middle schools; proviseurs for high schools. Many also teach classes, and thus may be considered both teachers and administrators.

“School administrators”: May include principals, supervisors, bursars, treasurers, stewards, and others.

“Education professional”: Teachers, school administrators, members of teachers’ unions, or local education officials (such as basic education district inspectors).

School year in Burkina Faso: October to June.

School levels in Burkina Faso:

- Primary school (école primaire): grades CP1, CP2, CE1, CE2, CM1, CM2

- Post-primary school / middle school (école post-primaire, or collège d’enseignement générale): grades 6ème, 5ème, 4ème, 3ème; BEPC exam

- Secondary school / high school (école secondaire, or lycée): grades seconde, première, terminale; BAC exam

- Note: some combined schools include both post-primary and secondary levels.

I. Conflict and Education in Burkina Faso

Spreading Armed Islamist Activity

Across the West Africa portion of the Sahel—a vast semi-arid region south of the Sahara Desert—armed conflict and violence among non-state armed groups and national armed forces, underscored by the growing presence of armed Islamist groups, has led to a humanitarian and security crisis. In Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso, over 4,000 people were killed in 2019 alone, according to one estimate, and over 1.1 million people were displaced by early 2020.[1]

In January 2020, the United Nations called the levels of violence “unprecedented.”[2] Perpetrators of violence against civilians include armed Islamist groups allied to Al Qaeda and the Islamic State; ethnic self-defense or separatist groups; and state security forces. Human Rights Watch previously reported that abusive counterterrorism operations and unlawful killings of suspects in custody, as well as abusive self-defense groups, are widely believed to have pushed many into the ranks of the armed Islamist groups.[3]

A landlocked nation of 20 million people, Burkina Faso spiraled from a largely peaceful—while imperfect—democracy in 2016 to a country struggling in 2020 to cope with over 830,000 people displaced from their homes, 2.2 million people (including 1.2 million children) in need of humanitarian assistance,[4] and attacks of varying frequencies by armed insurgents across at least 7 of its 13 regions. In January 2020, a state of emergency was extended in provinces of six regions for another year.[5] The number of killings multiplied from about 80 in 2016 to over 1,800 in 2019, according to the UN.[6]

The growing presence of armed groups in Burkina Faso is linked to insecurity in neighboring Mali, where northern regions fell to separatist Tuareg and Al-Qaeda-linked armed groups in 2012.[7] From 2015, armed Islamist groups spread to central Mali, and from 2016, with the emergence of Ansaroul Islam, into Burkina Faso.[8] Initially concentrated in Burkina Faso’s Sahel region, armed Islamist activity steadily spread to the Nord, Est, Boucle du Mouhoun, and Centre-Nord regions, which together have suffered the bulk of the attacks, as well as to Centre-Est and Centre-Sud. Additional attacks have occurred in other regions.[9]

A patchwork of groups with shifting and overlapping allegiances are involved in—and have claimed responsibility for—the attacks, including the homegrown Burkinabè armed Islamist group Ansaroul Islam, the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), and Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and its affiliates, notably the Group for Support of Islam and Muslims (JNIM).[10]

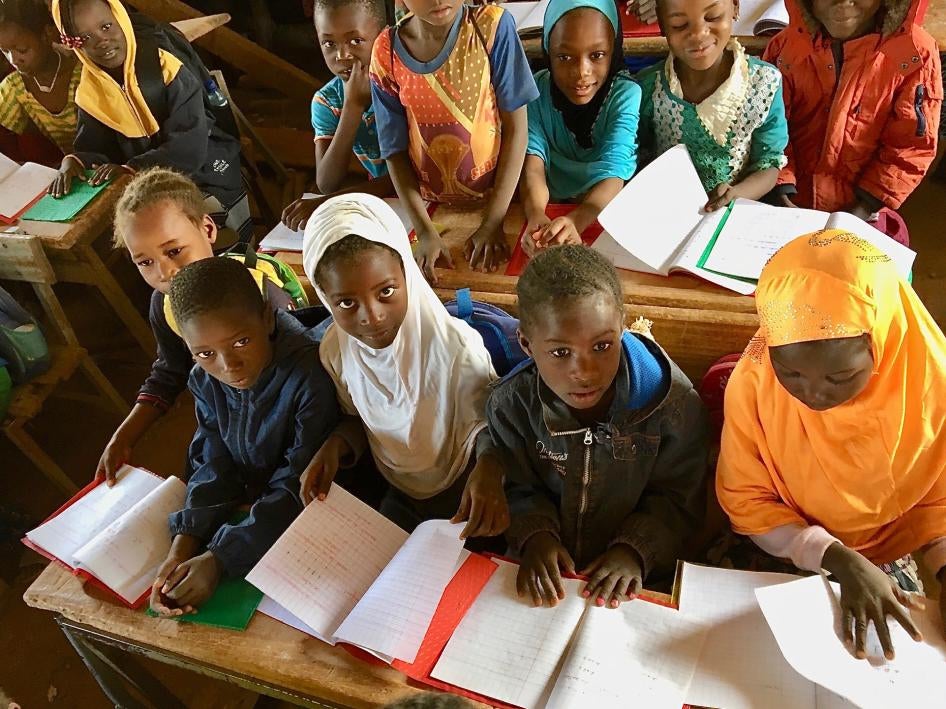

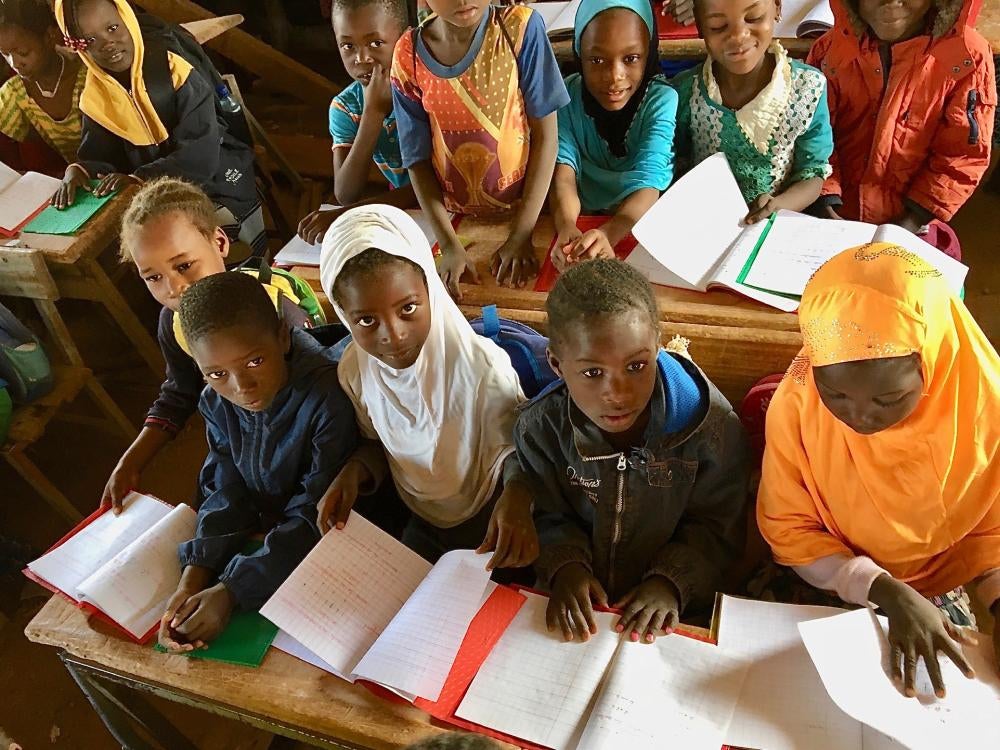

Education in Burkina Faso

Burkina Faso’s 2007 education law declares education a “national priority,” guarantees everyone the right to education, and makes schooling compulsory from ages 6 to 16. The law guarantees free basic public education, excluding registration fees.[11]

In practice, public education in Burkina Faso is not free. Communities frequently take on responsibility for constructing primary school buildings and teachers’ housing or keeping school supplies stocked. As a result, community parents’ associations, which manage much of the upkeep of local schools, often impose registration fees on students. This remains a financial barrier to education for many families.[12]

Schools in Burkina Faso include government public schools, private schools accredited by the government, and unaccredited private schools. Traditional Quranic schools (foyers coraniques) are not integrated into the formal education system.

Even prior to the security crisis, Burkina Faso’s education system faced serious challenges including lack of qualified teachers, overcrowded classrooms, insufficient infrastructure and teaching materials, low completion rates, and gender bias.[13]

Many school buildings remain unfinished, lacking boundary walls for protection and sufficient classrooms, desks, or materials. In rural areas, schools often operate under a thatched canopy outdoors.[14] Public school teachers are frequently deployed to areas outside their localities of origin, and many schools include teacher housing located on school grounds or nearby. However, in schools without housing, some teachers sleep in classrooms, offices or warehouses.[15]

The government made notable progress during the decade prior to the conflict in improving girls’ access to education. For example, primary school net enrollment rates[16] for the 2001-2002 school year were 30 percent for girls and 42 percent for boys; completion rates were 23 percent for girls and 34 percent for boys. As of the 2015-2016 school year, prior to the conflict, primary school net enrollment rates were 71 percent for both girls and boys; completion rates were 61 percent for girls and 55 percent for boys. For post-primary (middle) school, girls had also achieved parity with boys in enrollment rates, and near-parity in completion rates.[17]

Nevertheless, girls in Burkina Faso still face particular barriers impacting their education, including high levels of child marriage, female genital mutilation, and sexual violence and harassment in and en route to school.[18] Although the government adopted a strategy to prevent teenage pregnancies, some school officials still reportedly ban pregnant girls from school due to social norms and stigmas.[19]

Gender disparities persisted in access to secondary education both prior to and during the conflict, with girls still lagging slightly behind boys in secondary (high) school enrollment, and even more so behind boys in secondary school completion.[20]

Negative Consequences of the Conflict on the Education System

The conflict and attacks on education have greatly compounded the preexisting challenges and further eroded education infrastructure. Frequently, attacks on teachers or schools not only resulted in the closure of the school concerned, but provoked “cascades” of school closures and the panicked flight of teachers from neighboring communities.[21] Additionally, at least 62 schools were used by displaced people seeking shelter in 2019.[22]

As of March 10, 2020, the education ministry reported that 2,512 schools were closed due to insecurity—a surge of more than 1,000 schools since the end of the previous academic year—affecting 349,909 students and 11,219 teachers.[23] This meant that around 13 percent of Burkina Faso’s schools (preschool to secondary) had already closed due to attacks or insecurity prior to the Covid-19 outbreak, which resulted in the closure of all schools from mid-March.[24]

Of the five regions most affected by the conflict-related school closures, Sahel region topped the list in early March with a reported 947 schools closed (80 percent of the region’s schools), followed by 556 schools in Est (38 percent), 366 in Centre-Nord (21 percent), 357 in Nord (18 percent), and 239 in Boucle du Mouhoun (13 percent). The remaining closed schools were in Centre-Est (46) and Centre-Sud (1).[25]

While enrollment and completion rates for primary, post-primary, and secondary school in Burkina Faso had increased every year between 2015 and 2018, they decreased for the 2018-2019 school year for primary and post-primary school,[26] likely in response to surging attacks during that period.

Prior to the Covid-19 crisis, the Burkinabè government had reopened at least 840 schools as of early March 2020,[27] in addition to other steps to ensure continued access to education for displaced children and those affected by school closures. These efforts are examined in section VIII.

|

Burkina Faso: School Enrollment and Completion Rates During the Conflict |

|||||||||

|

2017-2018 School Year |

|||||||||

|

|

Primary |

Post-Primary (Middle School) |

Secondary (High School) |

||||||

|

Girls |

Boys |

All |

Girls |

Boys |

All |

Girls |

Boys |

All |

|

|

Net enrollment rate |

74.1% |

74.4% |

74.3% |

29% |

26.2% |

27.6% |

4.7% |

6.1% |

5.4% |

|

Gross enrollment rate |

90.9% |

90.6% |

90.7% |

54.6% |

49.6% |

52% |

14.5%, |

20.6% |

17.6% |

|

Completion rate |

67.6% |

58.8% |

63% |

42.1% |

39.2% |

40.6% |

11.9% |

17.7% |

14.8% |

|

2018-2019 School Year |

|||||||||

|

|

Primary |

Post-Primary |

Secondary |

||||||

|

Girls |

Boys |

All |

Girls |

Boys |

All |

Girls |

Boys |

All |

|

|

Net enrollment rate |

72.7% |

72.8% |

72.7% |

28.4% |

24.9% |

26.6% |

6.1% |

7.1% |

6.6% |

|

Gross enrollment rate |

89.2% |

88.4% |

88.8% |

54.1% |

47.1% |

50.5% |

19% |

24.2% |

21.6% |

|

Completion rate |

66.3% |

57.4% |

61.7% |

41.7% |

36.3% |

39% |

12.9% |

17.8% |

15.4% |

|

*Rates in red show decreases from prior year, likely due to increasing insecurity and attacks on schools. |

|||||||||

Data source: MENAPLN, “2018/2019 Statistical Yearbooks” for primary, post-primary and secondary school.

II. Perpetrators of Attacks on Teachers, Students and Schools

Most of the attacks on students, teachers, and schools documented by Human Rights Watch were unclaimed. However, the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) and Ansaroul Islam identified themselves or claimed responsibility in a few cases.

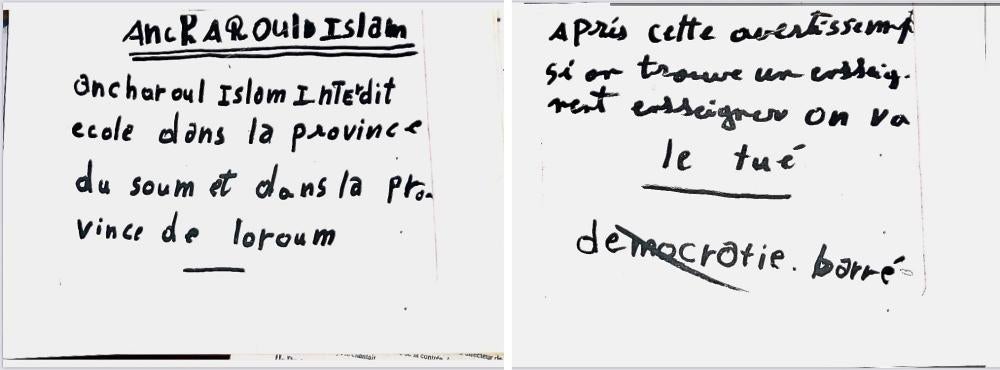

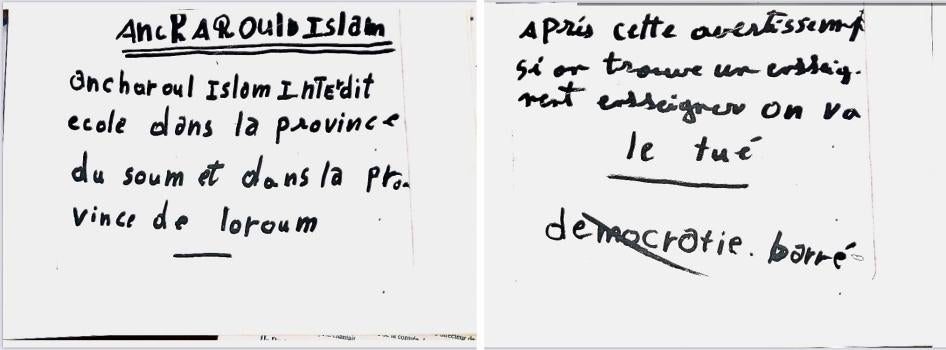

During a November 2018 attack on a middle school in Toulfé, Nord region, in which five teachers were whipped and the school burned, the attackers orally stated they were with Ansaroul Islam and left a signed note.[28]

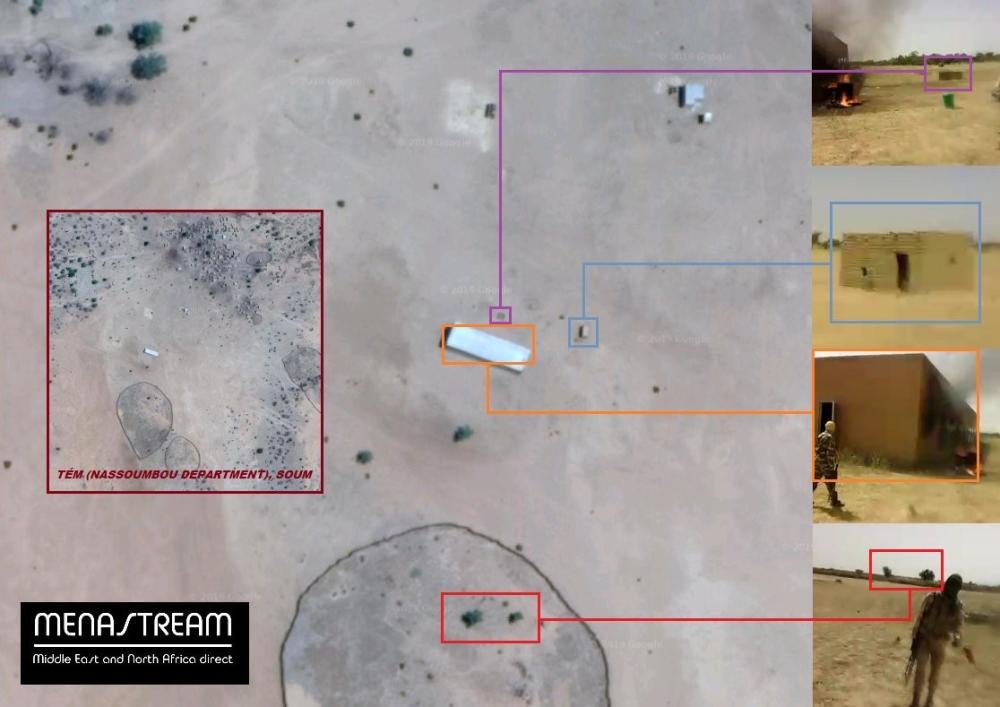

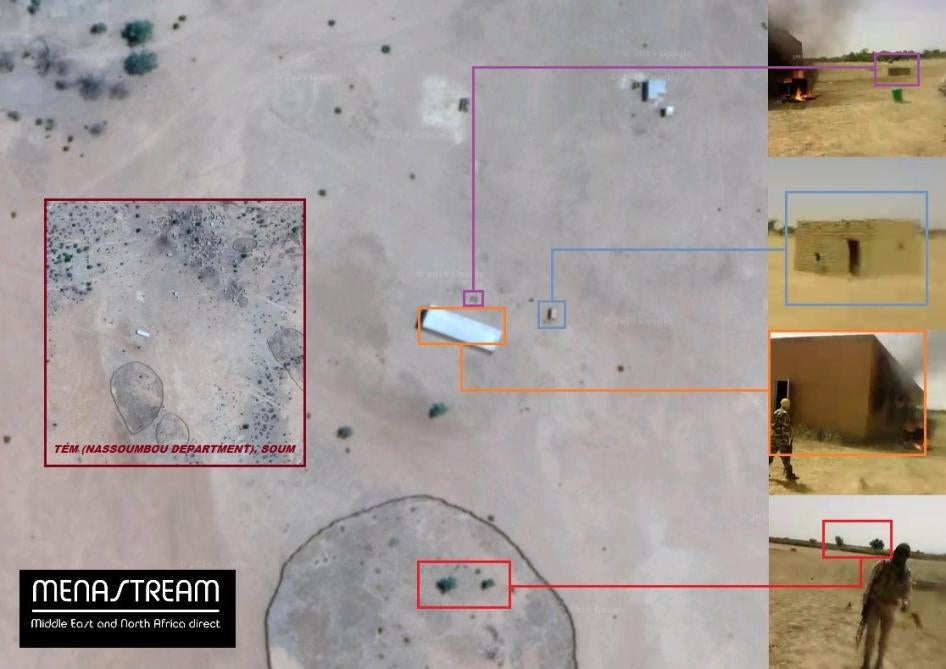

ISGS reportedly took responsibility for the April 2018 abduction of primary school teacher Issouf Souabo in Soum province, Sahel region.[29] Additionally, in a video circulated in early 2019—which reportedly depicts the October 19, 2017 burning by several armed Islamists of a school in Tem commune, Soum province, Sahel region—attackers spoke Fulfulde and Arabic and “identified themselves as ‘soldiers of the Islamic State in Burkina Faso and Mali [ISGS],’” according to an analyst for the Middle East and North Africa security research group MENASTREAM.[30]

During a 2018 attack on a primary school in Centre-Nord region, according to an eyewitness, armed men carried a black flag with white Arabic script similar to both Al Qaeda and Islamic State flags.[31] In a 2020 attack on a school in Est region, armed men told teachers “they were jihadists” and ordered them to stop classes.[32]

Witnesses, community members, and security sources widely presumed armed Islamist groups—most notably Ansaroul Islam, but also ISGS and the Group for Support of Islam and Muslims (JNIM)—to be behind the unclaimed education-related attacks across the country.

In dozens of cases documented by Human Rights Watch, survivors recounted that the perpetrators—typically armed with Kalashnikov military assault weapons, wearing either military uniforms or longer traditional garments (boubous), and often wearing turbans with their faces covered—gave speeches before, during, or after their attacks stating their position against education and issuing threats. In nearly all cases, attackers stated that they were against “French education,” “classic education,” or the education of “whites”; and that teachers “should only be teaching Arabic” or the Quran.[33]

Attackers typically issued variations of the same threat, as recounted by scores of witnesses: “If we return and find anyone here [at the school] again” or “anyone here teaching in French,” “we will kill you.” They often denounced “anything connected to the government,” to “whites” or to “Europeans.”[34] All of these threats aligned with the stated ideology of armed Islamist groups.

III. Attacks on Teachers and Education Professionals

Attacks and abuses against teachers, principals, school staff, and other education professionals—anyone perceived to be promoting government-run, French education in Burkina Faso—have steadily increased since 2017, when the first principal, Salifou Badini, was killed in Sahel region. These attacks, mostly targeting teachers, have included killings; violent assault; physical restraint including tying, chaining and blindfolding; robbery and destruction of personal property; and threats and intimidation. Principals, many of whom also teach, were often sought out for particularly harsh treatment.

Human Rights Watch documented the execution-style killings between 2017 and 2020 of 15 people allegedly targeted by armed Islamist groups for their connection to education. Human Rights Watch also documented the assault, abduction, or detention of 20 education professionals by presumed armed Islamists between 2018 and 2020. Abductions lasted between a day and two months.

Incidents took place in six regions: Sahel, Nord, Centre-Nord, Boucle du Mouhoun, Est, and Centre-Est. During seven attacks, assailants also damaged or destroyed school infrastructure or materials. Seven attacks were perpetrated in front of students.

In dozens of other cases documented by Human Rights Watch, teachers and school employees were threatened, often with death, and ordered to cease teaching in French or to leave the locality. In some cases, teachers were also robbed or suffered destruction of personal property.

Among the cases documented, all of the education professionals targeted for the gravest attacks—killings, violence, abduction—were men. Both male and female teachers were victims of threats, intimidation, robbery, and property destruction. According to survivors and witnesses, victims were of various ethnicities including Mossi, Peuhl, Gourmantché, Bobo, and Foulsé, while attackers most frequently spoke Fulfulde (a language of the ethnic Peuhl), followed by Moore (spoken by the Mossi), Gourmantché, Dioula, French, and, in at least one instance, Tamasheq (spoken by the Tuareg or Bella).

In a May 2020 letter to Human Rights Watch, the education ministry reported that 222 education workers had been “victims of terrorist attacks,” including 12 killed and others who were assaulted, robbed, or had their property destroyed.[35]

Targeted Killings

No one claimed responsibility for the 15 killings documented by Human Rights Watch, which included 12 education professionals killed in seven attacks between March 2017 and February 2020, and three construction workers killed at a school in April 2019. The attacks took place in Sahel region (six killings), Centre-Est (five), Nord (three), and Est (one).

Of the 12 education professionals killed, nine were working in public schools at the time; two were teachers reportedly working for local education authorities; and one was a village chief and retired teacher who taught on a voluntary basis. Ten individuals were shot, while two were beheaded. Seven were killed in front of students.

Several teachers and community leaders suggested to Human Rights Watch that two early teacher killings, in 2017, may have been reprisals by Ansaroul Islam against teachers who had joined Ansaroul founder Malam Dicko’s early religious association Al-Irchad—receiving benefits such as land, houses, and debt repayment—but who had refused to support the group’s evolution into an armed insurgency.[36]

However, relatives, witnesses, analysts, and education professionals attributed many subsequent killings of teachers to armed Islamists’ broader agenda of stopping “French” education and ridding territory of government workers, though there may also have been additional motivations for the attacks.[37]

February 2020 (Nord): School Administrator Abducted, Killed

The body of Ali Zorome, an administrator at Loroum Provincial High School in Titao, was found by soldiers near Samboulga village in Sollé commune on February 22, 2020.[38] A teacher at Zorome’s school said: “[Zorome] had gone to visit his family in Sollé, and he’d left on February 8 to return. Along the way, he was abducted. ... The next day when they called his phone, somebody else answered, so they knew something had happened. [The abductors] held him for two weeks.”[39]

While the motivation behind the killing is unclear, attacks against schools and teachers had previously taken place in Loroum and neighboring provinces, suggesting that Zorome’s profession may have been a factor. Two days later, in the neighboring province of Yatenga, two cases of teachers “brutalized” and “intimidated” by armed men were reported in the localities of Tangaye and Bossomnoré.[40]

December 2019 (Est): Village Chief, a Volunteer Teacher, Killed

The night of December 28, 2019, armed Islamists attacked the family compound of the Gourmantché community village chief in Nadiabonli village, in Partiaga commune, Tapoa province. The attackers shot and killed the chief, Kondjoa Marcellin Tankoano, who also volunteered as a teacher and tutored students. “We the family know this [attack] was linked to education, because he was the only intellectual in the village... and he taught those that needed help... and [the armed Islamists] were against this,” said a relative.[41]

The chief, about 75, had previously worked as a teacher in Cascades region, according to relatives. Upon retirement, he returned to his village, oversaw the construction of a middle school funded by private donors, and taught there as a volunteer, in addition to tutoring children in the evenings.[42] A family member said:

The schools in the commune were already under threat... Just two to three kilometers away, [armed Islamists] had kidnapped teachers. ... By late 2019, the middle school was functioning irregularly. ... The chief often went to the school to help teach, since there were frequently teachers absent. In the evenings, he helped children who hadn’t understood the lessons.

That night, around 9 p.m., he was giving exercises in math, physics and chemistry to students. ... He was in [his family] courtyard, seated on his terrace, where he had a chalkboard to write the lessons. The children were on benches that he’d made himself. Suddenly, armed men entered the royal court, shouting, “The chief, the chief, where is he?” There was a struggle, and they shot him in the head in front of the students. They are still traumatized.[43]

Another relative noted, “They had burned schools [in Partiaga], and it stung him to see young girls and boys out of school. After teachers started fleeing, he said he’d continue to teach. ... He was someone who truly had a heart for education.”[44] A teachers’ union representative said that after seven schools were attacked in the commune in 2019, many had closed. “The chief had encouraged teachers not to leave,” he said. “After he was killed, all the commune’s schools closed for a month.”[45]

October 2019 (Sahel/Nord): Principal Abducted, Killed

On October 26, 2019, the body of Souleymane Ouedraogo, principal of a primary school in Pobé-Mengao in Soum province, was found in Rounga village in Ouindigui commune, Loroum province. According to a government communiqué, “on his return from a teacher’s conference held in Djibo, [Ouedraogo] was abducted on Friday, October 25, 2019 by a group of armed individuals, at around 2 p.m.”[46] A member of the Kogleweogo self-defense militia in Ouindigui described seeing Ouedraogo’s body:

We heard shots fired the night before around 6 p.m., and we waited until the morning. Some of the population sent us a message to come... So we went to Rounga village, some 20 of us Kogleweogo militia. ... We saw the body two meters from the road, at the marketplace. They had shot him in the head. He was lying on his stomach... part of his head had been blown away.[47]

April 2019 (Centre-Est): Five Teachers Killed in School

The deadliest attack against teachers took place on April 26, 2019 in the village of Maytagou, Koulpélogo province, when armed men shot five teachers at the public primary school. The victims included the principal and two teachers—Désiré Bancé, Dieudonné Sandwidi, and Pakiemdan Sabdano—as well as Alassane Yougbaré and Hamad Bouda, two teachers at the Centre à passerelle (a “bridging center” reintegrating children into the education system), which operated in one of the classrooms.[48] A witness said that a sixth teacher was spared to be a “messenger to tell everyone in Burkina [they] don’t want anyone teaching French.”[49]

The witness said that about 10 armed men arrived on motorcycles in the late afternoon, while students were still in class. They wore military attire, and some had their faces covered with turbans. They spoke French, Moore, and Fulfulde. The teachers tried to run, but were caught, and the attackers fired in the air as warning.[50] The witness recounted:

When they arrived, some students fled, but others the jihadists rounded up to bring them into the classrooms... maybe 50 or so students, ages 6 to 16, were there. ... One of the teachers, Mr. Yougbaré... since he [resisted], they let him fall [in the schoolyard], and they shot him three times – in the head, stomach, and thigh. He was the first one they killed. ... [The attackers] gathered papers, documents, clothes, and set fire to it all inside the warehouse... Then they had the other teachers bring them their motorcycles. ... They said, “Didn’t you hear we’d told the population that we didn’t want you to teach French? ... Didn’t you follow the TV or the radio?”...

They took the principal and two teachers in front of the warehouse... They took Mr. Bouda separately in front of the building with the CP1, CP2, and CE1 classrooms. One started to shoot Mr. Bouda. He fired three shots, and with each shot he said “Allahu Akbar.” Then three others started to shoot the principal and the two teachers—they also shot them three times in the head, stomach and thigh, also saying “Allahu Akbar.” ... When they killed Mr. Bouda, it was in front of classrooms where the students were. Some were watching. The youngest were crying.[51]

A student’s parent said:

The next morning, I went to the school and found the five bodies on the ground... they’d been shot in the head and body. My son [age 8] and brother’s children [ages 7 and 13] had been at school that day... The children were traumatized... The school was closed, and they were not able to complete the school year.[52]

April 2019 (Sahel): Three School Construction Workers Killed

On April 19, 2019, armed men killed three workers building teachers’ residences at a primary school in Djika village, Arbinda commune, Soum province.[53] A villager who was at his home, some 300 meters away, said he saw around 20 to 30 armed men entering the school. “They found three people at the school, and they killed them. They were a 26-year-old contractor and two masons, ages 35 and 32,” he said. “The next day at 6 a.m., I went to the school and saw the bodies. They’d been shot in the head. ... I also saw they had burned the school hangar [a covered area], forced the doors, burned the desks and the teachers’ offices.”[54]

March 2019 (Sahel): Two Teachers Abducted, Killed

On March 19, 2019, the decapitated bodies of two primary school teachers, Judicaël Ouedraogo and Al-Hassane Cheickna Sana, were found on the road near Koutougou, Soum province. The teachers, both men, had been abducted on March 11 while traveling by motorcycle from Kongoussi, Centre-Nord region, to Djibo, Sahel region, where they worked.[55] Ouedraogo previously taught at a primary school in the Djibo area until late 2018, when he transitioned to working for the local education authorities in Djibo.[56]

A member of the Kogleweogo self-defense militia in Koutougou recounted finding the bodies on the road:

On March 18, around 6 p.m., I heard shots from the direction of the Koutougou CSPS [health center], around 800 meters from the village exit. I thought it was the [security forces] who were shooting, but the next day between 6 and 7 a.m.... we saw two unknown bodies lying next to the CSPS, on the road. Their [heads] were cut—they had removed the heads and placed them on the back of each body. Both were positioned on their fronts, hands tied behind their backs, and feet also tied.[57]

Another Koutougou resident, who helped with the burial, said: “They had their national IDs on them... That’s how we learned they were teachers.”[58]

Rigobert Ouedraogo, Judicaël’s father, said:

[Judicaël] was 28 years old and had a lot of ambition. He wanted to continue his studies... He was engaged to be married, and he left behind an 18-month-old daughter... I think they fell into an ambush intended for another vehicle... But he had his ID card, his computer, papers that showed his profession... Maybe if he hadn’t been a teacher or worked for the state, they would have let him go. After the attack, many teachers fled the area.[59]

A teacher from the Djibo area said: “After this, all the schools of Soum province closed for two months. I was in Djibo when I heard, and then I took a bus to Ouagadougou... I’ve stayed here ever since.”[60]

November 2017 (Nord): Three Teachers Shot, One Killed

During the night of November 26, 2017, armed men attacked the residences of several high school teachers in Kain, Yatenga province, killing French and history-geography teacher Souleymane Koumaya and wounding two other teachers. The attack provoked the flight of local government officials and the closure of several schools.[61]

Witnesses and a school official said the motive for the attack remained unclear but that they suspected the armed Islamists, primarily because of the town’s close proximity to areas of Mali where armed Islamist group presence was well-established. One witness recounted:

At around 10:15 p.m., I saw a few of the teachers chatting outside their house. Souleymane was inside preparing his lessons. Suddenly, there was the sound of a motorcycle… [A]rmed men shot at the teachers’ house, breaking the windows. They went inside, killing Souleymane and wounding two others. As the armed men left, they stole two motorcycles.[62]

March 2017 (Sahel): Principal Killed

The first reported killing of a teacher in Burkina Faso took place on March 3, 2017 in Soum province, when alleged armed Islamists fatally shot Salifou Badini, the Kourfayel primary school principal, along with another villager, Hamadoum Tamboura.[63] A witness said:

I was having tea at a friend’s house, 100 meters from the school, when we heard gunshots. ... [The students] had gone out for recess. ... Some students were playing in the courtyard... I saw two armed men wearing turbans enter the school courtyard on motorcycles. They shot in the air and headed toward the principal. ... Badini was a friend of my friend. Tamboura was a parent—I knew him, he had two students at the school. ... They were having tea at Badini’s house, around 50 meters from the school. ... [The attackers] shot him first, then Tamboura. ... They said [in Arabic] “La illaha illallah” before shooting five or six times in the lower abdomen.[64]

Abduction and Assault

Human Rights Watch documented nine attacks in which a total of 17 teachers, principals, or school employees were abducted or assaulted by presumed armed Islamists between 2018 and 2020. Eight individuals were beaten severely; at least seven were tied up, chained, or blindfolded. Seven were abducted for periods ranging from one day to two months. Eight attacks occurred on school grounds; one principal was abducted from the road.

In six of these cases, attackers also damaged or destroyed school infrastructure or materials. Four attacks were perpetrated in front of students. In nearly all cases, armed men threatened the education professionals and ordered them to stop teaching in French or to leave the region.

January 2020 (Est): Two Teachers Abducted, Robbed, and Beaten

In January 2020, around noon, armed men burst into a village school in Est region while class was in session.[65] The attackers fired shots in the air, scaring the children, who began running out of the classrooms. A teacher described seeing 10 armed men in the courtyard: “They had Kalashnikovs [assault rifles], and some were wearing khaki, like police uniforms... Some were turbaned.”[66] The men captured two teachers, stripped them of their belongings, and plundered the school of motorcycles, phones, money, bags, and some discarded backpacks children had left behind.[67] One teacher said:

They intercepted me... One [attacker] came over and said in Fulfulde, “We should cut his throat.” But another said, “Take him.” So he took off his turban and used it to tie my hands behind my back. ... There was a covered area situated between two of the school buildings, and they set it on fire. ... One of them removed the gasoline from a moto-tricycle and tossed it in my classroom, on top of my documents, and set it alight.

After setting the fires, they told us to get on their motorcycles. We were each flanked between two guys. ... On the way, we stopped, and they blindfolded me. Then we continued and stopped a second time, in the bush. ... They asked, “What type of education do you give to the students, French or Arabic?”...

They started beating [my colleague] first, then me. I couldn’t see, because I was still blindfolded, but they used a whip of some type... the blows hit us on our backs. ... They said, “You knew we didn’t want you here teaching, and still you dared to continue... You have defied us.” They said if they come back and take us a second time, it will be to remove our heads.[68]

The second teacher recounted a similar story. “They beat me with a whip, 10 blows on my back. ... It still hurts, even now,” he said in February.[69] The attack led to closure of several schools in the area.

December 2019 (Boucle du Mouhoun): Two School Employees Threatened, One Beaten

In an attack on a village school in Tougan commune, Sourou province, the night of December 10, 2019, armed men reportedly beat the school guard, threatened a school administrator at his residence, and set fires in the school.[70]

The administrator said that he saw around 20 armed men arrive at the school, dressed in military attire and carrying walkie-talkies; some covered their faces with turbans. He explained:

They broke the door [of my house]... and entered. ... They asked me where the teachers were. I said they lodged in the village, but I didn’t know where exactly. ... They asked me if there was a storeroom with food supplies. They had me open the door [of the administrative building]... but there was almost nothing in the storeroom, only two bags of rice... In my office... they piled all the books and documents on the ground, poured a canister of gasoline, and set it alight. Then they set a fire in the storeroom, and in [another] office. ... They said to tell the teachers they didn’t want to see anyone teaching there. One said, “Under the regime of [president] Roch Marc Christian Kaboré, there will be no school.”

As the men forced him outside, the administrator noticed the guard “tied up with his hands behind his back.” Before the group left, he heard them beating the guard.[71] Three months later, the school remained closed, with many of its 383 students still in the village.[72]

November 2019 (Boucle du Mouhoun): Principal Abducted

In late November 2019, armed men abducted the principal of the Biron village high school, in Bourasso commune, Kossi province. A teacher from Biron primary school reported that armed men on motorcycles entered both schools in the village on the day of the kidnapping, causing students and teachers to flee. The principal was allegedly abducted while walking to his residence, and released a few days later in Koudougou, some 160 kilometers away. “The next Tuesday [when he returned to Biron] I spoke with him, but... he couldn’t respond. ... he seemed traumatized,” the teacher said.71F[73]

October 2019 (Sahel): Two Teachers Assaulted, Schools Burned

One night in October 2019, during attacks on the grounds of two village primary schools in Yagha province, two teachers were restrained and one beaten.[74] A dozen armed men surprised the first teacher at his residence at the school at 11:30 p.m. The men threatened him with death, set fires, and stole teachers’ phones and motorcycles. The teacher recounted:

They grabbed my arms and tied them behind me, with a rope. ... [They] entered my house and gathered my belongings—school documents, my diploma, clothes, everything... and set it on fire. ...[T]hey burned the other two teachers’ houses as well... They asked me, did I still teach French? I said yes, and they said they wanted me to teach Arabic only... they said I should convert to become a Muslim. ... After they finished burning everything... they untied me and left. The school has been closed ever since.[75]

At the second school, around midnight, assailants found the teacher sleeping in a classroom, as the school had no teachers’ housing. The teacher said:

I heard the noise of motorcycles outside... They said to come out showing my hands... There were around ten of them, heavily armed—even the police that I’ve seen don’t have these types of weapons! They had belts with lots of ammunition, rocket-launchers, Kalashnikovs, knives. One guy even had three guns... They grabbed my arms and chained them behind my back with the chain from the door. They entered and said, “We will kill you, but we’ll first see what’s in the house.”... I thought, “Today is the end of my days.” ... They took everything—my motorcycle, bags, phones, clothes, food supplies, everything—then gathered all the documents inside the classroom and set them on fire.

They told me to go sit... and the leader came over... they knew I was a Muslim... They said I’d taken the wrong path, and instead of teaching French I should teach in Arabic. ... They said... since I asked in the name of God, they wouldn’t cut my throat—but they would beat me with 10 strokes of the whip. But if they ever saw me in this school again, or another school, they would kill me. They used the cables from the solar panels—one [of them] beat me 10 times, and another took over and hit me an eleventh time, but another blocked his hand and said, “Leave it.”[76]

The principal, who was away the day of the attack, noted that the school closed the very next day due to the “fear and psychosis.”[77]

April 2019 (Est): Three Teachers Abducted

On April 19, 2019, three teachers from a village primary school in Partiaga commune, Tapoa province, were allegedly abducted and held for three days.[78] A teachers’ union representative for Partiaga who had investigated the incident described what happened:

Around 5 p.m., the jihadists came to the primary school. ... They gathered three [teachers]... and took them away on motorcycles into the bush. Some students saw what happened... [The teachers] spent three days and two nights with the jihadists… They had stolen their motorcycles, clothes, bottles of gas, and phones. ... When [the armed Islamists] dropped them at the school, they whipped them. ... After this, we suspended all [school] activities in Partiaga for a month.[79]

November 2018 (Nord): Five School Employees Beaten

The afternoon of November 12, 2018, armed men infiltrated a middle school in the village of Toulfé, in Titao commune, Loroum province. They arrived while the teachers and students were in class, forced five school employees—the principal, two administrators, and two teachers—out of their classrooms and offices, berated them and beat them. The attackers spoke Fulfulde and French. A survivor recounted:

We were already living in psychosis—we knew that one day or another the jihadists would come, so the students were constantly looking out the window. They saw when the men arrived that day. The children started screaming, jumping out the classroom windows, running... One [attacker] pointed his gun at me—he carried an AK47 [Kalashnikov] and was wearing military uniform. His face was covered, but he removed his turban before speaking. He said he was in the group Ansaroul Islam and he was there for jihad. He said... they’d already said to stop teaching French, so why were we still teaching French? ...

He took a paper out of his pocket, a message, and asked us to transmit it to the Burkinabè authorities. ... The message said they no longer want any French education in Soum and Loroum provinces. ...

They took out some kind of whip or belt... They beat us one at a time, really hard... Everyone was beaten, all five of us. Afterwards, there were marks, and it hurt to lie down. ... Some students in [grade] 4ème hadn’t had time to run away—the jihadists had told them to get down quickly or they’d shoot, so they were there watching when they beat us. ...[T]hey were crying.[80]

Before leaving, the men set fire to one of the school’s offices. A parent, who arrived at the scene shortly after, recalled: “At the school we found the fire still burning. We found the teachers there who had been beaten, some so severely that they couldn’t speak... They were in shock.”[81] The school remained closed following the attack.

May 2018 (Centre-Nord): Principal Assaulted, Residence Burned

In May 2018, armed men attacked a village primary school principal on school grounds in Sanmatenga province.[82] Two other teachers escaped.[83] The principal said:

It was around 3 p.m. on a Wednesday, which is a half-day, so we had already released the students at noon. I was preparing lessons for the next day [when] they surprised me at the residence, which is also my office. ... I went out and found six armed men on three motorcycles. They had war weapons—I think Kalashnikovs, with ammunition belts. They wore turbans and military uniforms, and they had a black flag with white writing in Arabic. ...

I’m a Muslim, so I started reciting Surahs of the Quran. … They blindfolded me and pushed me down... One kicked me in the head... They demanded where was my money, the key to my motorcycle, my phones. ... They said, “You have knowledge of the Quran, so why didn’t you use it to teach?” ... They told me to stop teaching French, and said they no longer wanted to see me in the school. ... I heard them set a fire in my house. After the motorcycles left, I stayed on the ground for two hours... When I got up, I found everything charred—there was nothing left in my house.[84]

After the attack, the school closed, and its 303 students were unable to finish the year. The school reopened in late 2018 but closed again due to insecurity in early 2019.[85]

April 2018 (Sahel): Two-Month Abduction of Teacher

On April 12, 2018, Issouf Souabo, a teacher in Bouro village, Nassoumbou commune, Soum province, was abducted from school by six armed men, in an attack that also resulted in the killing of student Sana Sakinatou, who was shot but not targeted.84F[86] The Islamic State in the Greater Sahara took responsibility for the abduction on April 17, informing the media that Souabo had been targeted for teaching in French.[87]

Several sources, including two witnesses, described to Human Rights Watch what happened. One witness recounted: “At around 4 p.m., when children were in class, around five armed men came to the school. They fired a round of shots in the air—people started running. ... [Souabo] was not able to escape—he was taken by force by the attackers… they left toward the North.”[88] Another said: “We heard gunfire outside, and the children started screaming and running. ... [The armed men] grabbed [Souabo]... They said they’d told teachers to leave the area, but [they’d] stayed, so that’s why they came.”[89]

The attackers forced Souabo to his home, stole his possessions, and took him away by motorcycle to an unknown location, where they kept him blindfolded and tied with his arms behind his back for almost two months. They freed him in June 2018, but he suffered long-term physical pain as a result of the attack. He no longer works as a teacher.[90]

Threats and Intimidation

In dozens of other cases documented by Human Rights Watch, presumed armed Islamists threatened, harassed, and intimidated education professionals to cease teaching in French, or to leave the locality. These cases occurred as individuals were intercepted on the road while traveling, at individuals’ homes, during diatribes by armed men to village populations, and at schools during attacks or threatening visits. Cases in which teachers were threatened in the presence of their students during attacks on schools are described in section V.

Detained on the Road

In addition to the four abovementioned cases of teachers abducted from the road and killed, Human Rights Watch documented three cases of education professionals detained and threatened by armed men on the road. Two took place in May 2019 in Est and Centre-Nord regions.[91] In December 2018, armed men detained a teacher in Centre-Nord region on the road between Bollé and Pissila. The teacher said:

They were three men—turbaned with black scarves, faces covered. I could only see their eyes. ... They asked me if I was a teacher. I was shaking and sweating. I said, “No, I'm a trader.”...They told me to get on my knees and I said to myself: “Here it is, the day of my death.” But after a minute of silence... they said, “You're lucky you’re not a teacher, otherwise they’d have to come get your carcass.” Then they let me go.[92]

Visits to Residences

In several cases, armed men visited education professionals’ homes for threats or attacks. The night of April 19, 2019, in the town of Deou, Oudalan province, Sahel region, armed men visited a high school teacher at his residence. He recounted: “They said, ‘We know you very well, we know where you live, and we want you to stop teaching. We’re giving you 72 hours to leave town.’” He left town a few days later.[93]

In late October 2019, in the town of Tankougounadié, Yagha province, Sahel region, armed men came and shot up the house of the basic education district inspector, who was sleeping elsewhere. “We think his house was specifically targeted,” said the secretary-general of a union for education professionals.[94]

Threats in Front of Villagers

In early April 2019, a group of presumed armed Islamists visited Goenega and Yatenga villages, in Barsalogho commune, Centre-Nord region. In both villages, they ushered villagers to the marketplace to deliver a diatribe, voicing their disapproval of French education. A teacher who witnessed the event said:

Around 5 p.m. on Friday... some 17 men arrived on motorcycles. They wore turbans, with uniforms resembling those of the military or police… heavily armed, with rocket-launchers, Kalashnikovs, bullet magazines. ... The weapons that I saw in front of me that day, I’d never seen in my life except on TV. They surrounded the market... They said they came to promote Islam, and they don’t agree with teaching in French... They said teachers had 72 hours to leave or teach Islam; otherwise if they come back and find them not teaching Islam, they “know what will happen to them.”[95]

Teachers from both villages fled shortly afterwards. [96]

IV. Attacks and Abuses Against Students

Dozens of cases documented by Human Rights Watch show that armed Islamist groups have threatened, intimidated, and harassed students in order to force them to stop attending school. In several cases, both in and outside of school, attackers burned students’ books, documents, or notebooks in front of them. Human Rights Watch did not find any cases of children intentionally targeted for violence during attacks on schools. Indeed, many education professionals, parents, and security experts claimed that students are “not the target” of armed Islamist groups.[97] Nonetheless, in 2019, at least two students were injured or killed by stray bullets during attacks on or near schools. Students have also been killed in numerous attacks outside of school, though the motivations for these killings are unknown.

Students Killed and Injured During Attacks

January 2020 (Boucle du Mouhoun): Seven Students Killed in IED Attack

The worst attack affecting students took place on January 4, 2020, in Sourou province. As a convoy of three public transport buses traveled on the road between the towns of Toéni and Tougan, one of the buses hit an improvised explosive device (IED), killing 14 people on board, including 7 students. At least 19 others were injured in the blast, including several students. The convoy had been carrying 160 passengers, many of whom were students. No one claimed responsibility for the attack. [98]

Schools in Toéni had closed in December 2018 due to armed Islamist attacks on and threats against schools in the area, causing hundreds of students to enroll in schools in Tougan and elsewhere. The day of the attack, the students in the convoy were returning to schools in Tougan and other cities after holidays with family in Toéni.[99]

A teacher who knew five of the seven students killed said:

Jacqueline Djerma, 17 years old, was doing her 3ème [grade] in Dédougou... She was good in class, very participatory. Sirina Sawadogo, 19 years old—she was doing her terminale in Ouagadougou. She was a girl who loved literature... Welhore Sidibe was 22 years old; she was doing her first year of university in Koudougou. Harouna Djerma, 23, was doing his première in Bobo[-Dioulasso]. Ousmane Koussoubé, 13, was continuing his 5ème in Tougan.[100]

The teacher said a sixth student casualty was Issaka Teri, and that the seventh body presumed to be a student was not identified.[101]

A 22-year-old high school student injured in the attack said: “I was on top of the vehicle, up on the roof where the bags were. ... I heard a huge noise, and I found myself in the air. ... When I came to, I was under [a pile of] things... There was black dust mixed with smoke... I was injured on my foot and head.”[102] His friend Harouna was among the students killed: “He was a really nice guy, friendly, always made people laugh... It has affected me to the point that I can’t sleep,” he said.[103]

A 16-year-old student, who had also ridden on top of the bus, said: “It threw me in the air. The bus was split in half, and it fell over... I was injured on my knee and hand. I saw my classmates dead in the bus.”[104]