Summary

Sara was a 17-year-old high school student when separatist fighters occupied her school, causing her to flee her hometown in Cameroon’s North-West region out of fear. She decided to move to the capital, Yaoundé, to finish her education. On the way, she was stopped by armed separatists, who searched for items she had relating to education, tore up her schoolbooks and notebooks, and warned her that worse would befall her if she was found with such materials again. In Yaoundé, she could not afford the school fees, and had to seek work, which she found at a pineapple company. After working for two years, she abandoned her dream of finishing school.

In the South-West region, Clara the head teacher at a government school, refused to abide by the separatist-ordered education boycott. When separatist fighters broke into her home in March 2019 to extort and punish her, she paid 30,000 CFA (US$56) and more in blood: they inflicted wounds all over her body, cutting her right hand so severely it had to be medically amputated, and losing the use of her left hand.

The stories of Sara and Clara are unfortunately all too common experiences for students and teachers in Cameroon’s North-West and South-West regions who, since 2017, have become victims of attacks by armed separatists on education.

These attacks have become a hallmark of the crisis in the country’s Anglophone regions, which has resulted from the post-independence political, economic, cultural, and social marginalization felt by the Anglophone minority, who live in Cameroon’s North-West and South-West regions. Although Cameroon is a bilingual and bijural country, many Anglophones believe the government is trying to sideline and assimilate their education and legal systems into the dominant Francophone system.

Tensions escalated in October and November 2016 and again in September and October 2017 when Cameroonian security forces used excessive force against peaceful protests led by teachers and lawyers. Different Anglophone armed separatist groups have since emerged and grown, and education soon became a primary battleground.

Separatist fighters began to order and enforce school boycotts, including by attacking scores of schools across the Anglophone regions. They have also used school buildings, such as Sara’s school, as bases for storing weapons and ammunition as well as holding and torturing hostages. Separatist fighters have also attacked, intimidated, or threatened thousands of students, education professionals, and parents in their attempts to keep children out of school. These attacks, the resulting fear, and the deteriorating security situation have caused school closures across the Anglophone regions, denying students access to education.

While armed separatists bear full responsibility for their targeted attacks on education, the response by the Cameroonian government and security forces has been insufficient and is hampered by the fact that they have conducted many abusive counterinsurgency operations in the English-speaking regions which sewed deep distrust among the civilian population victimized in those operations. Sometimes the abusive operations have also had a direct impact on education. For example, the report documents security forces burning at least one school which was being used by armed separatists as a base. Therefore, while enhanced security should offer protection to students and teachers, in practice many students and teachers also fear abuses from the security forces.

Based on telephone interviews conducted between November 2020 and November 2021 with 155 people, including 29 current and former students as well as 47 teachers and education professionals, this report documents attacks on students, teachers, and schools, as well as the use of schools by armed separatist groups, in the North-West and South-West regions between March 2017 and November 2021. It also examines the impact of those attacks, which have denied approximately 700,000 students an education. After describing the Cameroonian government’s responses, it highlights gaps and, more importantly, potential solutions that the Cameroonian authorities, in collaboration with their international partners, should implement to stop and address attacks on education.

Attacks on Students, Teachers, and Schools

Separatist fighters have killed, kidnapped, assaulted, threatened, or extorted hundreds of students and teachers while at school, on the way to or from school, or at home. Human Rights Watch does not claim to have documented all or even the majority of such attacks, but believes what it has documented indicates the scope of the problem, and disproves any claims that these are isolated problems. Human Rights Watch documented the killings of eleven students and five teachers: seven students were killed during an attack on their school in Kumba, South-West region, three students and one teacher were killed during an attack on their school in Ekondo-Titi, South-West region, while the eleventh student and the other teachers were killed while they were at home or on their way to or from school. Human Rights Watch also documented the death of two schoolgirls caused respectively by a gendarme and a police officer shooting at vehicles which failed to stop at checkpoints. Human Rights Watch documented the kidnapping of at least 268 students and education professionals by armed separatists between January 2017 and August 2021. In two incidents alone, one in 2018 and another in 2019, fighters kidnapped 78 and 170 students, respectively, from their schools in the North-West region. Most of the victims (255) were students, while nine were teachers and four were principals. Victims said that the separatist fighters targeted them because they were going to school.

At least 70 schools have been attacked in the Anglophone regions since 2017, according to reports from United Nations agencies, the World Bank, Cameroonian and international civil society organizations, and media outlets. Human Rights Watch documented in detail 15 attacks on schools by separatist fighters between January 2017 and November 2021. Armed separatists visited schools, ordering their closure, threatening and terrorizing students and teachers, and destroyed school infrastructure and property, including with fire.

Human Rights Watch documented the occupation, between early 2017 and March 2019, of at least five schools by separatist fighters in the North-West region. They used schools as bases, and also held hostages and stored weapons and ammunitions in them. Some moved from school to school, like the ones who took over Sara’s school. In one case, evidence suggests Cameroonian security forces burned a school building that had been used by separatist groups.

Government Response

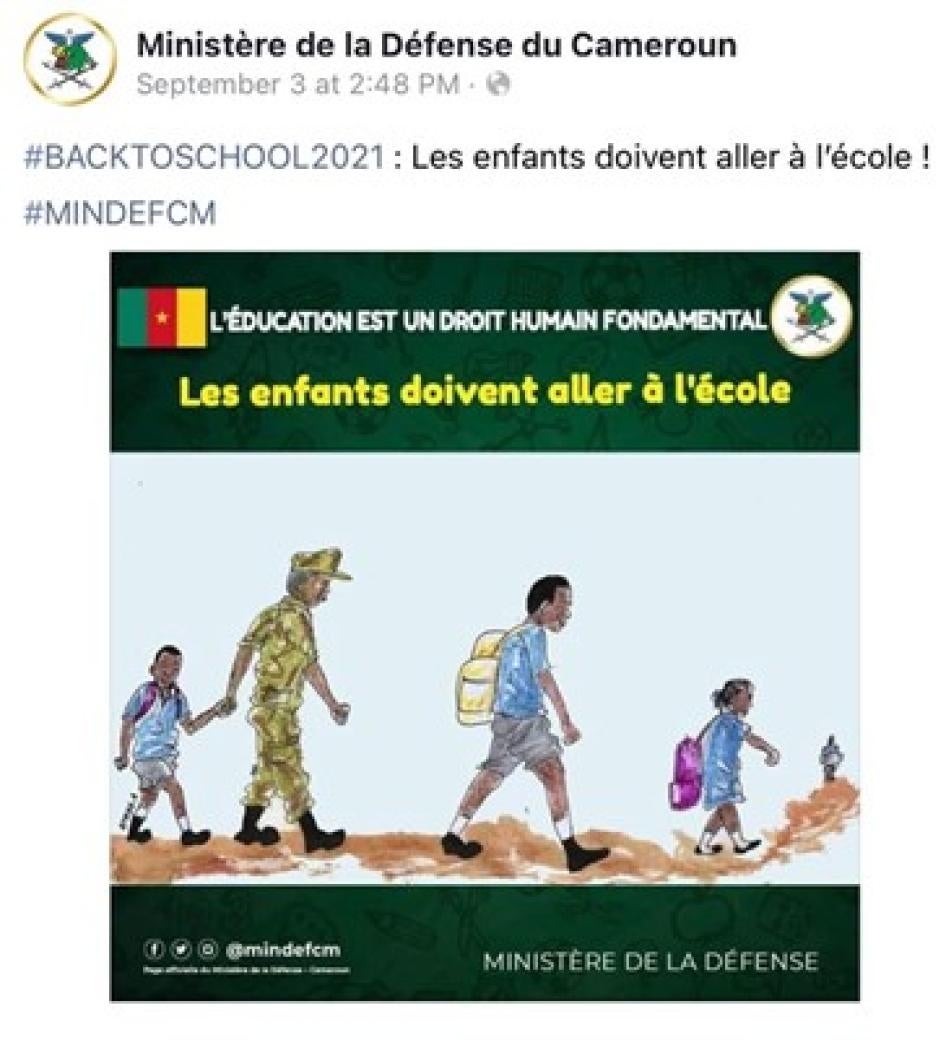

The Cameroonian authorities have taken steps to respond to attacks on education, including by endorsing the Safe Schools Declaration – an intergovernmental political agreement to protect students, teachers, and schools during armed conflicts – in September 2018. In line with its commitments to ensure that students are able to continue their education, the government has conducted more robust back-to-school campaigns in the Anglophone regions. It has also stationed security forces in or outside schools, mainly in major urban centers, to increase safety. However, there is almost no such security presence in rural areas or on roads leading to and from schools. More importantly, students and teachers have had mixed reactions to the deployment of security forces in or outside schools, as some believe their presence increases the risk of being targeted by armed separatists. There is also an urgent need for the government to address the lack of resources and overcrowding in schools whose populations have doubled, or even tripled, due to the need to accommodate internally displaced students.

By signing up to the Safe Schools Declaration, the Cameroonian government agreed to protect education, including by investigating and prosecuting perpetrators of attacks on students, teachers, and schools. Clara, unlike the vast majority of victims of attacks on education, has experienced a degree of justice, as at least one of her alleged assailants was arrested and is currently facing trial. This is not the norm: in addition to the arrest made in her case, Human Rights Watch is aware of only two sets of arrests for attacks on schools since 2017 – one set involves the arrest of 10 persons after a 2019 attack on a university, the other involves the arrest of 12 persons following the October 24, 2020 attack on the school in Kumba. The fate of the 10 suspects arrested in 2019 is unknown, and the trial of those arrested in connection with the Kumba school massacre, held before a military tribunal, failed to meet basic fair trial standards. This suggests that the separatists have enjoyed almost absolute impunity for their attacks on education.

Consequences of Attacks on Education

School closures because of the boycott orders or attacks on schools by separatist fighters, fear of being targeted for studying, and economic challenges have all caused students to drop out of school, robbing young people in the Anglophone regions of their right to education. This has only been exacerbated by further school closures related to the Covid-19 pandemic. The trauma of experiencing or witnessing an attack, which is exacerbated by the lack of psychosocial support services, has affected students’ ability to learn and caused many teachers to change professions. This will have longer term effects on their economic and social mobility as individuals and on the development of the regions and Cameroon as a whole. This report describes not only the emotional harms, such as those experienced by Sara and Clara, but also the resilience of the students and teachers who struggled to continue their studies and work, respectively, which sometimes required choosing to relocate.

Nearly 600,000 people have been displaced by the crisis unfolding in the two English-speaking regions—a figure which likely includes thousands of teachers and students—and were forced to flee and begin a new life elsewhere. This report also documents the experiences of displaced students and teachers, highlighting the specific hardships faced by older teachers.

Ensuring the Right to Education in Cameroon

International human rights law obligates the Cameroonian government to respect, protect, and fulfill the right to education, and in signing up to the Safe Schools Declaration the government committed to take steps to prevent attacks on schools and mitigate their impacts. Unfortunately, the attacks by armed separatists have continued, largely unabated, causing students, parents, and teachers to suffer enormously. Absent urgent action to address the lack of access to education caused by separatist attacks, many students will lose out on an education, and may face a bleak future with reduced socioeconomic opportunities.

The government of Cameroon which bears the primary responsibility for guaranteeing the right to education should promptly provide access to alternative forms of education, including community education, distance learning, radio learning, and temporary learning spaces to students who are out of school because of the crisis, including rural and displaced students. Those responsible for attacks should be arrested and prosecuted, and an accessible reparations program, including physical rehabilitation and psychosocial support services, should be made available to victims and their families. The Cameroonian government should consider establishing two special task forces, one to assess and make recommendations regarding investigations and prosecutions of attacks on schools and the other to support the re-establishment and continuation of access to safe education for all.

Cameroon’s international partners, such as Canada, France, Italy, Switzerland, the United States, the United Kingdom, the European Commission, the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the African Union, should provide financial and technical support to ensure that the special task forces and reparations program are adequately resourced and sustainable.

During times of crisis, ensuring access to education is crucial because safe and protective environments like schools can provide a sense of normalcy essential to children’s development and psychological well-being. All stakeholders in the Anglophone crisis should take immediate action to prevent yet another generation in Cameroon from losing out on an education. Leaders of separatist groups should immediately announce an end to the school boycott and instruct fighters to cease all attacks on students, teachers, and schools.

Key Recommendations

To Leaders of Separatist Groups

- End the school boycott as well as attacks and threats against students, teachers, education officials, and schools, publicly announcing that this policy and tactics have been ended.

- Issue statements and disseminate pamphlets, leaflets, and instructions among members and fighters explaining and endorsing the need to comply with international human rights law.

To Armed Separatist Groups’ Fighters

- Cease all human rights abuses, including killing, torturing, kidnapping, extorting, and threatening civilians, including students and teachers.

- Immediately cease all recruitment of children under 18 years old.

- Immediately release all kidnapped civilians, including students and teachers.

- Immediately cease using schools for any purpose, including for bases, storage, and detaining individuals.

To the Cameroonian Government

- Ensure students deprived of educational facilities because of the crisis are promptly given access to alternative accessible forms of education, such as community education, distance learning, and temporary learning schools or spaces, with suitable equipment and adequately trained teachers. Education should be accessible to children with disabilities.

- Establish a credible and inclusive reparations program, through a transparent and participatory process, to support victims of attacks on education and their families. Such a program should be sensitive to the needs of women and men, boys and girls, and address the needs of students and families living with disabilities and those in hard-to-reach areas.

- Consider establishing two special task forces, one to assess and make recommendations regarding investigations into attacks on education and prosecutions of perpetrators; the second to further the re-establishment and protection of access to education for all on an equal basis (see Section XI: “The Way Forward.”)

To the Cameroonian Police and Gendarmerie

- Effectively investigate, for the purpose of prosecuting, government agents, members of the security forces, separatist leaders, and fighters responsible for human rights crimes committed in the Anglophone regions, including attacks on students, teachers, and schools.

To the Cameroonian Judicial Authorities

- Ensure victims of human rights crimes by all sides have access to effective and accessible remedies, including complaint mechanisms, witness protection, and the opportunity to participate in a transparent judicial process.

To the Cameroonian Ministers of Basic, Secondary, and Higher Education

- Effectively implement the Safe Schools Declaration, and work with relevant authorities, community leaders, and parents to ensure better security for schools in the Anglophone regions.

- Ensure teachers and administrators are not pressured to reopen schools in insecure zones without appropriate, effective security measures.

- Expand and improve efforts to collect data on attacks on students, teachers, and schools and the use of schools by armed separatist groups, including the dates and locations of attacks, types of school attacked, disaggregated information about victims and suspected perpetrators, and the number of students and teachers affected.

To the Cameroonian Security Forces

- Ensure security operations in the Anglophone regions respect and protect human rights, including by abiding by the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR) resolution on the Prohibition of Excessive Use of Force by Law Enforcement Officers in African States and the United Nations Basic Principles on the Use of Firearms, respecting principles of necessity and proportionality, and deploying military judicial police officers on operations to monitor the conduct of security forces, report abusive members to commanding officers, and advise commanding officers on human rights issues.

- Ensure that, if armed forces personnel are engaged in security tasks related to schools, their presence within school grounds or buildings be avoided if at all possible, including for accommodation. Where necessary, establish wider security perimeters in neighborhoods around schools, rather than directly outside schools, to minimize disruption to children’s education and avoid compromising the school’s civilian status.

To the African Union (AU)

- Advocate for more comprehensive and sustained measures to protect education from attack in Cameroon’s Anglophone regions by calling on the Cameroonian government to prioritize security of schools, students, and teachers, including the assessment of any security risks for schools which are currently open.

- Engage proactively with the Cameroonian government and support its efforts to expand and strengthen monitoring and reporting on attacks on education and military use of schools, including by collecting and reporting disaggregated data.

- Encourage and support the Cameroonian government to implement fully the commitments contained in the Safe Schools Declaration at all levels of education.

To the African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (ACERWC) and to the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR)

- Call on the Cameroonian government to conduct impartial, transparent, and independent investigations into attacks against students and teachers, including physical assaults, killings, abductions, threats, and attacks against school buildings. Urge Cameroonian authorities to publicize the findings of these investigations, prosecute those responsible in fair trials, and incorporate lessons learned into future protection measures and strategies to prevent attacks against education.

To the AU Peace and Security Council

- Include the situation in Cameroon’s Anglophone regions as a priority item on the AU peace and security agenda, request a briefing by the ACHPR and the ACERWC on the human rights and humanitarian situation in the Anglophone regions, and demand an end to human rights abuses.

- Unequivocally condemn attacks against education in Cameroon’s Anglophone regions and play a more assertive role, including by applying coercive political and diplomatic tools at its disposal, such as imposing targeted sanctions on separatist leaders and fighters responsible for attacks against students, teachers, and schools.

To the United Nations (UN)

To the UN Secretary-General

- Continue to include Cameroon as a situation of concern in the annual report on children and armed conflict to the UN Security Council. Include in the annex of the report any parties engaging in violations against children. Ensure voices and experiences of children with disabilities are included.

To the UN Security Council

- Formally include Cameroon as a priority item on its agenda, request a briefing by the UN Secretary-General on the situation in Cameroon, and demand an end to human rights abuses.

- Establish a sanctions regime in Cameroon, including targeted sanctions such as travel bans and asset freezes, against individuals credibly implicated in serious abuses, including attacks on education.

To the UN Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict

- Ensure accurate, public monitoring and reporting on threats and attacks on students, teachers, and schools as well as the military use of schools and use of schools by armed separatist groups.

To the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF)

- Improve its mechanism in cooperation with NGOs and other UN agencies to monitor and report threats and attacks on students, teachers, and schools, and the use of schools by armed groups and other grave violations against children committed in the context of the Anglophone crisis.

To the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR)

- Make publicly available the findings of its 2019 investigations and any future investigations into the Anglophone crisis.

- Actively monitor the situation in the Anglophone regions.

To the UN Country Team in Cameroon

- Under the formal Monitoring and Reporting Mechanism on children and armed conflict, actively document and verify incidents of grave violations against children, including threats and attacks on students, teachers, and schools, and the use of schools by armed groups, and provide this information to the UN Special Representative to the Secretary-General for children and armed conflict.

To Cameroon’s International Bilateral Partners, including Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Switzerland, the United States, the United Kingdom, and the European Union

- Privately and publicly urge the Cameroonian government and security forces to adopt and support the implementation of the above recommendations.

- Urge the national authorities to empower the investigative police, including its forensic criminal evidence gathering, judicial investigation, prosecutorial, and trial capacity and provide targeted and specifically monitored support.

- If established, provide technical and financial support to the special task forces on attacks on education and to reparations program to support victims of attacks on education and their families.

- Ensure any support to the Cameroonian security forces does not contribute to or facilitate human rights abuses.

- Implement targeted sanctions, such as travel bans and asset freezes, against individuals credibly implicated in serious abuses, including attacks against education.

To The World Bank

- Ensure that a significant amount of the US $97 million provided to Cameroon’s government in support of education sector reform is used to improve access to safe schools in the Anglophone regions, including by assisting displaced students and teachers, rebuilding and repairing damaged or destroyed school buildings, supporting, if established, the special task forces on attacks on education and the reparations program to support victims of attacks on education and their families.

Glossary

Amba boys: terms used by some Cameroonians to refer to armed separatist fighters in the North-West and South-West regions.

Ambazonia (or Republic of Ambazonia): term used by some people from the North-West and South-West regions to refer to a self-declared state announced by pro-separatist groups and constituting the North-West and South-West regions of Cameroon.

Anglophone regions: the North-West and South-West regions, Cameroon’s two minority English-speaking regions among the country’s 10 administrative regions.

Attacks against education: Human Rights Watch uses the following definition of “attacks against education” provided by the Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack: “Attacks on education are any intentional threat or use of force—carried out for political, military, ideological, sectarian, ethnic, religious, or criminal reasons—against students, educators, and education institutions.”

CFA: refers to the Central African CFA franc, Cameroon’s currency (CFA stands for Communauté Financière Africaine, African Financial Community).

Child: In accordance with international law, Human Rights Watch defines “child” as a person below the age of 18 years.

Education professional: Teachers, principals, school administrators, members of teachers’ unions, or local education officials.

Francophone regions: Cameroon’s eight French-speaking administrative regions: the Centre, Littoral, West, North, Far North, Adamawa, East, and South regions.

Student: A “student” may refer to a child (under age 18) or an adult (18 or older).

Methodology

This report is based on 155 telephone interviews between November 2020 and November 2021, including with 29 current and former students, 47 teachers and other education professionals, and 15 relatives of students. The current and former students included 4 children (2 girls and 2 boys) and 25 young adults (9 women and 16 men). We also interviewed 64 others, including witnesses to human rights abuses, former separatist fighters, healthcare, social and humanitarian workers, lawyers, journalists, civil society representatives, United Nations officials, and diplomats. Interviewees included residents of Cameroon’s North-West and South-West regions.

Human Rights Watch conducted the interviews with the support of an extensive network of contacts in Cameroon. Interviews were conducted in French, English, Pidgin English, and local dialects, with the support of trusted interpreters who were physically with the interviewees for those interviews conducted in Pidgin English and local dialects.

Human Rights Watch informed all interviewees of the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, and how the information would be used, and we obtained oral or written consent for all interviews. We told all interviewees that they could decline to answer questions and end the interview at any time. Interviewees did not receive financial incentives or other benefits for speaking with Human Rights Watch beyond the reimbursement of their travel expenses, where applicable.

Nearly all victims of attacks and witnesses expressed serious concerns and fears of reprisals for speaking with us. Human Rights Watch has thus used pseudonyms and withheld identifying information of most of the victims and witnesses. We have withheld or replaced all children’s names with pseudonyms. Unless otherwise specified, we have noted interviewees’ ages at the time of the interview.

Human Rights Watch sought to address the limitations of telephone interviews by using secondary sources to corroborate findings. We examined reports by Cameroonian and international human rights and humanitarian organizations, national and international media, and government bodies in addition to photographs, video footage, medical records, and court documents.

Due to ongoing violence, challenges accessing the country and collecting information from remote areas, Human Rights Watch sometimes faced difficulties confirming the exact numbers of victims, circumstances, and alleged perpetrators of specific attacks.

In a July 27, 2021, telephone call with Felix Mbayu, Minister Delegate at the Ministry of External Relations in charge of relations with the Commonwealth, Human Rights Watch shared its preliminary findings for this report. Human Rights Watch also sent a letter, with its findings and a list of questions, to Prime Minister Joseph Dion Ngute and Mbayu on September 21, 2021. The Prime Minister had yet to reply at time of writing. The letter is available in Appendix II.

Human Rights Watch also shared its preliminary findings on September 22 with the leaders of four major separatist groups: the president of the Ambazonia Interim Government (Sisiku), Sisiku Ayuk Tabe; the spokesperson of the Ambazonia Interim Government (Sako), Christopher Anu; the president of the Ambazonia Governing Council, Cho Lucas Ayaba; and the chairman of the African People’s Liberation Movement, Ebenezer Derek Mbongo Akwanga. The letters sent to the leaders of the four major separatist groups are available in Appendix IV.

On September 27, 2021, Anu responded to Human Rights Watch during a Zoom call.

On September 29, 2021, Dr. Jonathan Levy, the legal representative of Akwanga, responded via email to Human Rights Watch and his full response is available in Appendix III.

On September 30, 2021, Akoson Raymond, secretary of the Department of Human Rights & Humanitarian Services of the Ambazonia Governing Council, responded via email to Human Rights Watch. His full response is available in Appendix VII. On October 10, 2021, Akoson also shared with Human Rights Watch via email a code of conduct of the Ambazonia Defense Forces, the armed wing of the Ambazonia Governing Council. The code of conduct is available in Appendix VI.

On December 6, 2021, Human Rights Watch received a letter dated November 29, 2021 signed by the “Leadership of the Ambazonia in prison”, headed by Sisiku, with a “Freedom Protocol” attached as an annex in response to Human Rights Watch’s request for information. Both the letter and the protocol are available in Appendix IX.

I. Background

Roots of the Anglophone Crisis and Separatism

Cameroon’s Anglophone crisis and separatist struggle are rooted in the country’s colonial history, tensions surrounding its independence, and Anglophones’ feelings of marginalization and concerns about assimilation into the Francophone system and culture.

The geographical area of modern Cameroon was originally a German colony, Kamerun, divided into French and British mandates after World War I. After gaining independence in 1961, Cameroon was a federation from February 1961 to May 1972, when Cameroonians voted to adopt a unitary government. Following decades of what they saw as marginalization by the Francophone-dominated government, in 1993, an “All-Anglophone Conference” convened in Buea, the former capital of the British territory, calling for a return to federalism. In response, the government pledged to adopt some reforms to decentralize power. The following year, a second “All-Anglophone Conference” issued the Bamenda declaration, recommending a two-state federal system or secession. However, the government maintained its support for the unitary system, causing Anglophone groups to begin calling for secession, including through diplomatic campaigns.[1]

The current crisis began after the government violently repressed peaceful strikes by Anglophone lawyers and teachers in October and November 2016. They were protesting what they perceived as the central government’s attempts to marginalize and assimilate Anglophone courts and schools into the Francophone system. Similar heavy-handed responses by security forces against peaceful protests to celebrate the symbolic independence of “Ambazonia,” the name given by secessionists to their self-proclaimed independent state comprising the North-West and South-West regions, occurred again between September 22 and October 2, 2017.[2]

Moderate voices began to fade, as armed separatists, many of whom are known locally as “amba boys” or “amba,” grew in number, profile, and support, both nationally and internationally. They began to attack security forces and government officials as well as order and enforce school boycotts and lockdown strikes (or “ghost towns”), requiring people to stay at home and not go to work in the North-West and South-West regions to pressure the government into granting greater political recognition to that area.[3]

Escalation of the Crisis in 2018 and 2019

In 2018, thousands of security forces were deployed to the Anglophone regions, where they conducted often abusive large-scale operations to locate and drive out armed separatists.[4] Armed separatists took control of some rural and urban periphery areas,[5] erecting roadblocks and checkpoints.[6] Separatists also continued to enforce school boycotts as well as weekly lockdown strikes.[7] Several upticks in the violence occurred from January 2018 to December 2019, including around presidential elections;[8] the arrest, detention, and trials of separatist leaders;[9] and lockdowns imposed by armed separatists.[10]

Ongoing Violence Since 2020

Around the February 2020 legislative and municipal elections, armed separatist groups kidnapped over 100 people, burned public and private property, and threatened voters in the period before the elections. Security forces did not adequately protect civilians; instead, they committed retaliatory abuses during the same period.[11]

In March 2020, the Southern Cameroons Defence Forces (SOCADEF), an armed separatist group, unilaterally called for a ceasefire because of Covid-19.[12] Notably, neither the government nor the other armed separatist groups have called for a ceasefire despite the rising toll of the pandemic.[13] Instead, after separatist fighters killed a police officer in September 2020, the government launched “Operation Bamenda Clean” to weed out separatists,[14] during which the security forces also abused civilians.[15]

In December 2020, separatist fighters marred Cameroon’s first regional elections[16] through boycotts, threats, and violent attacks.[17] Attacks by both separatists—on civilians,[18] government forces and authorities,[19] and the UN[20]—and by the army against civilians continued into 2021.[21] September 2021 marked a new escalation of violence with separatist fighters killing at least 15 soldiers and several civilians in two separate attacks in the North-West region using improvised explosive devises and an anti-tank rocket launcher.[22]

On October 5, Cameroonian Prime Minister Dion Ngute visited Bamenda, the capital of the North-West region, to follow up on the implementation of recommendations formulated during a national dialogue.[23] The same day, his public speech was interrupted by sustained gunfire, allegedly coming from separatist fighters. Ahead of Ngute’s visit to Bamenda, the Ambazonian Defence Forces (ADF), one of the main armed separatist groups, had ordered residents to stay at home, saying that anyone participating in meetings with Ngute could be at risk.[24]

Humanitarian Crisis

As a result of the Anglophone crisis, there are 573,900 internally displaced persons (IDPs) in the Anglophone regions as well as in the Francophone Littoral, West, and Centre regions.[25] In the Anglophone regions, 2.2 million people need humanitarian assistance.[26] The provision of basic services, including education and health care, has been disrupted.[27] Humanitarian access remains a challenge due to the volatile security situation and the targeting, by armed separatist groups, of humanitarian personnel,[28] with the UN recording at least 19 incidents of abductions involving humanitarians staff between April 2020 and August 2021.[29] Due to insecurity and separatist roadblocks across the Anglophone regions in August 2021 alone, 40,000 people could not receive humanitarian aid, according to UNOCHA.[30]

By 2021, more than 1.2 million school-aged children were in need of humanitarian assistance in the two Anglophone regions, and approximately 700,000 of them needed urgent access to education services.[31]

Since late 2016, up to 66,000 people from Cameroon have also fled to Nigeria.[32] Thousands more have left the continent for Europe or the United States.[33]

At least 4,000 civilians have been killed by armed separatist fighters or government forces in the Anglophone regions since late 2016.[34]

Economic Impact

The crisis has resulted in a significant contraction of the economies of the North-West and South-West regions, also seriously affecting the whole country’s economy.[35] According to the World Bank, “given the extent of destruction of productive assets, as well as the adverse effects of the crisis on the local credit market, the impacts may be lasting.”[36]

In the Anglophone regions, heads of households have been killed,[37] business have closed, and people have lost their jobs.[38] Displaced families have lost their livelihoods, so struggle to pay for food, housing, and their children’s school fees.[39] The violence has impacted thousands of farmers by displacing them,[40] thus increasing their risk of hunger and poverty as well as challenges providing for their children. Some parents in the Anglophone regions told Human Rights Watch they had to pull their children out of school because they could not afford the school fees and the associated costs of education, including books, uniforms, supplies, and transportation.[41]

The World Bank has estimated that “the combined effects of lower income due to reduced employment and increases in consumption prices due to supply chain disruptions inflicted a heavy toll on household welfare,” and that in 2019 “household welfare in the South-West and in the North-West regions was lower by 13.2 % and 21.2 %, respectively” compared to prior to the crisis.[42]

Responses to the Anglophone Crisis

The Cameroonian government and members of the international community began to respond strongly to the crisis in 2019, approximately three years after it started.

Cameroon’s Response

Amid increasing violence and sustained international pressure, President Paul Biya held a national dialogue, from September 30 to October 4, 2019, to address the Anglophone crisis. The dialogue, led by Prime Minister Joseph Dion Ngute, was attended by more than 1,000 delegates including government officials, clergy, teachers, and representatives of civil society.[43] However, main separatist groups, as well as major political opposition parties,[44] did not attend, and some opposition political leaders walked out in protest.[45]

The dialogue did not include victims of human rights abuses in the Anglophone regions.[46]

The dialogue resulted in a special status for the two Anglophone regions to re-enforce the autonomy of administrative areas.[47] The dialogue’s final report did not address human rights and accountability issues.[48]

The government held peace talks with detained leaders of the Ambazonia Interim Government (Sisiku) separatist group in April and July 2020.[49]

In a September 20, 2021, press release, Col. Cyrille Atonfack Nguemo, the army spokesperson, said that attacks carried out by separatist groups in September 2021 with the use of weapons that included improvised explosive devises and rocket launchers are “largely the result of” separatists “joining forces with other terrorist entities operating outside the country’s borders” and announced a “paradigm change” in ongoing military operations.[50] Contacted by the BBC, Atonfack refused to provide more information about any groups allegedly collaborating with and supporting the Anglophone separatist fighters.[51]

Addressing the general debate of the 76th Session of the UN General Assembly on September 27, 2021, Lejeune Mbella Mbella, Minister for Foreign Affairs, speaking on behalf of President Paul Biya, said Cameroon is “maintaining efforts in the North-West and South-West regions to end the socio-political tensions fueled by armed groups.” He added that measures taken by the government following the national dialogue, including the creation of a commission for the promotion of bilingualism and multiculturalism, the granting of a special status to the Anglophone regions, a disarmament, demobilization and reintegration program, a humanitarian assistance plan and a reconstruction plan, are already making “tangible results with a gradual return to peace, that “despite some isolated acts of banditry perpetrated by armed gangs, the situation is improving,” and that “our defense and security forces have been deployed on the ground to protect the population and their property with professionalism and respect for human rights.”[52]

Response of Regional and International ActorsThe key actions of UN, European, and US actors are highlighted below. March 2019: Thirty-eight members of the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) expressed deep concern about the deteriorating human rights situation in Anglophone regions and called on Cameroon to engage fully with the OHCHR.[53] April 2019: The European Parliament passed a resolution condemning violence in the Anglophone regions, expressing concern at the government’s failure to hold security forces accountable.[54] May 2019: The United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHCHR) visited Cameroon, met national authorities, and raised concerns over human rights abuses in the Anglophone regions as well as the lack of access for human rights workers.[55] The UN Security Council organized an informal session on the humanitarian situation in Cameroon,[56] putting the situation in Cameroon on Council members’ radars.[57] July 2019: Switzerland agreed to mediate talks between Cameroonian authorities and separatists.[58] October 2019: The US cut Cameroon’s trade privileges, citing persistent human rights violations in the country, including in the Anglophone regions.[59] February 2020: The UN Secretary-General, his special advisers, and the UNHCHR raised concerns over human rights abuses.[60] January 2021: The Vatican’s secretary of state visited Cameroon and expressed the Roman Catholic Church’s willingness to facilitate dialogue between the government and separatists.[61] May 2021: For the first time, the UN Secretary-General included the situation in Cameroon’s North-West and South-West regions as a “situation of concern” in his annual report to the UN Security Council on children and armed conflict. June 2021: The UN Secretary-General condemned the violence against civilians, schools, and UN and humanitarian personnel and property in the Anglophone regions. He encouraged Cameroonian authorities “to prioritize and promote inclusive dialogue and reconciliation.”[62] June 2021: The US secretary of state announced visa restrictions “on individuals who are believed to be responsible for, or complicit in, undermining the peaceful resolution of the crisis in the Anglophone regions of Cameroon.” He also condemned human rights violations and threats against advocates and humanitarian workers.[63] On November 25, 2021, the European Parliament adopted a resolution condemning rights abuses in Cameroon and urging the EU to work with regional actors including the AU and ECOWAS to facilitate dialogue. The Parliament urged, among others, the Cameroonian government and the leaders of separatist groups “to agree on a humanitarian ceasefire” and encouraged both parties “to agree on confidence-building measures, such as freeing non-violent political prisoners and lifting school boycotts.”[64] |

II. School Boycotts

They [the amba boys] say: “Don’t send your children to school. It’s not safe.” They tell us there’s too much insecurity and soldiers cannot be trusted. “If they get shot, it will be your fault. When Ambazonia will be freed, we’ll run the schools and you will send your children there.” That’s what they have told parents.

— Parent of two primary school children in the South-West region, May 2021[65]

At the beginning of the crisis in late 2016, as part of a civil disobedience campaign to create a new Anglophone nation called “Ambazonia,” Anglophone activist groups viewed a school boycott as a means to protest the perceived breakdown of the Anglophone regions’ separate education system and its assimilation into the French-speaking system.[66] However, by the end of 2017, separatist leaders started using school boycotts to disrupt normal life in the Anglophone regions, as leverage in negotiations with the Cameroonian government, and to mobilize international attention to the crisis unfolding in the North-West and South-West regions.[67]

Since 2017, armed separatists have consistently targeted school buildings and killed, kidnapped, assaulted, harassed, and threatened education officials and students for failing to comply with separatists’ demands to boycott education.[68]

According to Peter, a 24-year-old former separatist fighter affiliated with a group known as Asawana: “[Our generals] made us think it was nice and important to shut down schools… They said that if schools are going on, the world will think that there is no crisis in the Anglophone regions.”[69]

Anglophone Separatist Groups at a GlanceMost Anglophone separatists are organized around three main political bodies that have armed wings operating in both the North-West and South-West regions: · Ambazonia Interim Government (Sisiku), led by Sisiku Julius Ayuk Tabe, who is serving a life sentence for terrorism and secession charges at a high-security prison in Yaoundé;[70] · Ambazonia Interim Government (Sako), a splinter faction led by Samuel Ikome Sako, a pastor based in the US;[71] and · Ambazonia Governing Council, led by Norway-based Ayaba Cho Lucas.[72] The armed factions linked to the two “Interim Governments” are known as the Ambazonia Restoration Forces, which do not have a clear command structure and consist of various groups, such as the Terminators of Ambazonia, the Bui Warriors, the Red Dragons, and the Buffaloes of Bali, etc.[73] The armed wing of the Ambazonia Governing Council is the Ambazonia Defence Forces (ADF), headed by Benedict Kuah. There are also several other smaller separatist groups that do not fall under the three main groups, including: · African People’s Liberation Movement, which is led by US-based Ebenezer Derek Mbongo Akwanga and whose armed wing is the Southern Cameroons Defence Forces (SOCADEF);[74] · British Southern Cameroons Resistance Forces, headed by “General RK”; and · Tigers of Ambazonia, headed by Chia Martin aka “Tiger 1.”[75] As of 2019, there were approximately 2,000 to 4,000 separatist fighters in the Anglophone regions.[76] |

Separatist Groups’ Positions on School Resumption

In public statements and communications with Human Rights Watch, most separatist groups provided two main reasons for the school boycott: it is not safe for students to go to school due to violence, and the education provided in government schools is substandard and biased.

The Ambazonia Governing Council and its senior leadership have repeatedly stated that it will not allow schools managed by the Cameroonian government to function in the English-speaking regions.[77] In a May 26, 2021 official letter in response to Human Rights Watch’s questions about the Ambazonia Governing Council’s position on school resumption, its leader, Ayaba Cho Lucas, wrote:

Schools will remain closed in Ambazonia because of insecurity created by the failure of Cameroon to respect its obligations under international humanitarian law to respect schools and teachers as civilian objects and, most importantly, because of our opposition to the introduction or continuous usage of any colonial curriculum of education as the basis of knowledge in Ambazonia. The Ambazonia Governing Council has however facilitated, permitted, and opened community schools within areas of control of the Ambazonia Defence Forces and other sister forces.[78]

In a September 30, 2021 official letter in response to a request for information by Human Rights Watch, Akoson Raymond, secretary of the Department of Human Rights & Humanitarian Services of the Ambazonia Governing Council, said:

The People of Ambazonia have collectively rejected Cameroun’s colonial educational system. The Ambazonia Governing Council [AGovC] champions for the resumption of classes under an Ambazonian educational system. That is why, following the call of school boycott, the AGovC presented an alternative learning system under community schools run and managed by Ambazonians. Currently, Ambazonia boasts of fifty-four community schools throughout its territory. [79]

On May 19, 2021, Ebenezer Derek Mbongo Akwanga, chairman of the African People’s Liberation Movement and head of its armed wing (the Southern Cameroons Defence Forces), disapproved the resumption of government schools: “We support the education of our people, but we do not support a brain-wash educational system that has been imposed on our people for more than 60 years.”[80]

In a September 29, 2021, official letter in response to a request for information by Human Rights Watch, Dr. Jonathan Levy, Akwanga’s legal representative, said:

The respondents want to stress they support education […]. The situation in Ambazonia is a tragedy, children are not only insecure in their schools but even more so in their homes, towns, and villages. This appalling situation which is going on for more than four years now is the responsibility of the Republic of Cameroon.[81]

On May 18, 2021, Sisiku Ayuk Tabe, the jailed president of the Ambazonia Interim Government,[82] told Human Rights Watch: “We wish to see peace return to Southern Ambazonia so that our children can attend school in a nation that can guarantee their safety, security, and prospects for unadulterated and good quality education within a meritocratic and prosperous nation.”[83]

In a letter dated November 29, 2021, Sisiku vociferously objected to Human Rights Watch’s attribution of responsibility for many of the attacks on education to armed separatist groups, and among other things, stated:

I share your horror at the brutal attacks on minors, schools and educational professionals. These attacks are inconsistent with the principled political campaign for rights and self-determination of Ambazonians of which I am a part. One of the reasons we must work vigilantly to end this war by addressing the root causes is because of how war distorts the human spirit and draws out horrific behavior. […] We are unequivocally and vigorously against all actions that harm students and educational professionals, and we stand firm in asserting that the primary perpetrator of such harm is the Cameroon military and paramilitary forces, and that they must be called to account for this.[84]

On September 30, 2020, the president of the splinter faction of the Interim Government, Samuel Ikome Sako, tweeted that school resumption can only take place after the establishment of a “negotiated ceasefire or safe school zones supervised by the United Nations.”[85]

In a September 27, 2021 Zoom call with Human Rights Watch, Christopher Anu, the spokesperson of the Ambazonia Interim Government (Sako), said:

It was our policy from the beginning of this struggle […] that schools be shut down, that courts be shut down… That was the policy we had […] We revised the policy, taking cognizance of the insecurity and the safety situation on the ground. We said to the parents and the schools: “the decision to send your kids to school will be yours, not that of the interim government.” [The] decision to open will be that of the proprietors of the school, not that of the interim government.[86]

On November 12, 2021, Anu announced a renewed ban on all schools across the Anglophone regions, threatening violence against teachers, students, and school owners who violate the order.[87]

At the beginning of the 2020-2021 academic year, activists in different separatist groups, including Eric Tataw and Mark Bareta, changed their positions from opposing to supporting school resumption.[88] On September 28, 2020, Tataw urged the reopening of schools on Twitter: “I’m unapologetically asking all Ambazonian fighters & activists [to] join me in the crusade to allow school resumption.”[89] On September 29, 2020, Bareta tweeted: “School boycott is no longer a weapon of our struggle for independence. Thus, where possible, Ambazonia Forces should allow education and even encourage [going to] schools.”[90]

III. Attacks on Students by Armed Separatists

Many of my students do not wear school uniforms on their way to and back from school. If they wear them, they can be at risk of being spotted by the separatist fighters on the road and attacked. Also, they don’t use school bags. They put their books and notebooks in shopping bags like those we use to go to the market to buy food. Some also prefer to leave their books in my office. These are some of the coping strategies students have developed to keep safe.

— A 36-year-old chemistry teacher in Buea, June 2021[91]

Over 500 students have been attacked in the Anglophone regions by separatist fighters since 2017, according to reports from the UN and other credible organizations, as well as Human Rights Watch research. Human Rights Watch documented in detail 20 of those attacks which involved threats, intimidation, harassment, physical assaults, kidnapping, and even killings of students to force them to stop attending school. Human Rights Watch documented the kidnapping by separatist fighters of 255 students, including 78 who were taken from their school in Nkwen, North-West region, in November 2018, and 170 from their boarding school in Kumbo, North-West region, in February 2019.[92] In some cases, both in and outside of schools, attackers destroyed or seized students’ books, documents, or notebooks. Many students told Human Rights Watch that they go to school without wearing their uniforms for fear of being spotted and attacked by separatist fighters.

Students Human Rights Watch interviewed believed their attackers were separatist fighters because of their clothing (plainclothes or just military pants or camouflage t-shirts as opposed to full uniforms), accessories (including amulets), types of weapons (such as hunting guns and machetes), language (Pidgin English, English, and local dialects), statements that students should not go to school and schools should be closed, and extortion tactics commonly used by separatist fighters. When kidnappings occurred, the perpetrators took their victims to camps in often remote areas—as opposed to police, gendarmerie, or military stations or barracks—one of the common tactics used by armed separatists.

Attacks in the South-West Region

Five Public High School Students Kidnapped and Beaten, Bafia (September 22, 2018)

A 25-year-old high school student, Steve, said that five separatist fighters, armed with guns and machetes, kidnapped him and four other students, between 21 and 22 years old, including one woman, early in the morning on their way to school:

They beat me up, they hit me and my friends with sticks and machetes on the soles of our feet, in the arms, and in the back…. They cut my right hand. I had a serious wound, and I was bleeding…. They demanded a ransom of 500,000 CFA [$933]. My mom didn’t have that amount. She pleaded with them in tears and eventually gave them a sum of 200,000 CFA [US$373] for my release.[93]

Steve was released after two weeks. He said he was too afraid to return to school and hid in the bush for four months before relocating to Limbe, South-West region, where he now works as a driver and lives with a relative.[94]

Public University Football Team Kidnapped, Buea (March 20, 2019)

Suspected separatist fighters carried out an assault at the University of Buea’s football field and kidnapped at least 15 male football players from the university’s team.[95] Prior to the incident, on social media, suspected separatists had warned Anglophone teams to stay out of competitions organized by the Cameroonian government.[96] The students, some of whom were beaten, were released the following day, and the military arrested at least 10 suspects about a week later.[97] It is unclear whether a ransom was paid to secure the students’ freedom.[98] The fate of the 10 suspects is also unknown, although Human Rights Watch has sought information on their fate from the government.

Female Public University Student Kidnapped and Sexually Assaulted, Buea (June 13, 2019)

Six separatist fighters kidnapped Veronica, a 23-year-old University of Buea student, at about 3:30 p.m. They took her to an abandoned school in Bomaka neighborhood and sexually assaulted her before taking her to their camp in the bush, where they threatened her with death. They released her the next day following a ransom payment of 500,000 CFA (US$933). Veronica said:

On the road, I saw six amba boys following me. They were armed: two had guns. They stopped me and ordered me to follow them. They asked me to give them my school bag, which I happened to have with me, with my laptop and a book inside. I got scared and walked with them till the roundabout, when I pretended to collapse, just to call for attention. But no one came to rescue me, and [the separatist fighters] carried me. They took me first to an abandoned school, the Government Secondary School Bomaka, where they kept me for a few hours before taking me to their camp in the bush. In the school, one of them sexually assaulted me. They told me I was being kidnapped because I was a student, because I was going to school.[99]

Following the incident, she relocated to Limbe, South-West region for safety. She later returned to Buea to resume her studies in January 2020.[100]

Secondary School Student Kidnapped, Buea (January 30, 2020)

On January 30, 2020, armed separatists kidnapped Marie, a 19-year-old secondary school student, in Buea, in Cameroon’s Anglophone South-West region, on her way back from school. Three days later, they chopped her finger off with a machete.[101]

They were armed with machetes and knives. They found schoolbooks in my bag and seized it. They blindfolded me so I could not see where they were taking me. We had to walk for few hours. I was not given food. I slept on the ground outside for three days. The amba called my father and asked him to pay money for my release. On the third day, when I was about to be released, at 10 am, they cut my finger with a machete. One of the boys did it. They punished me because they found schoolbooks in my bag. They wanted to cut a finger of my right hand to prevent me from writing again. I begged them [not to], and then they chopped the forefinger of my left hand.[102]

Marie said the separatists also maimed a 19-year-old man who was held with her and also accused of attending school. Both students were released on February 3, after a ransom payment.

Human Rights Watch also reviewed photographs showing Marie’s finger wrapped in a bandage after medical treatment.

11 University Students Wounded in Explosive Attack, Buea (November 10, 2021)

According to media reports, an explosive device thrown on to the roof of a lecture hall at the University of Buea wounded at least 11 students.[103]

No one claimed responsibility for the attack, but media quoted “two security sources” as saying that the authorities suspected it was carried out by separatist groups,[104] while Horace Manga Ngomo, the University vice-chancellor, said that "an investigation will tell us who the perpetrators are."[105]

Attacks in the North-West Region

Public High School Student Threatened and Assaulted, Kumbo (late 2017)

Separatist fighters assaulted Tim, a 21-year-old student, on his way to school in Kumbo.[106] He recounted his experience: “They beat me up near my head. They punched me. They told me, ‘Why are you going to school? Schools should be shut. Why are you stubborn?’ I still have a scar on the back of my head as a result of the beatings.”[107] His mother knew about her son’s beating and independently informed Human Rights Watch about this incident.[108]

Public High School Student Harassed and Threatened, Mangu (January 2018)

Sara, 21, dropped out of school and fled Ndu town in 2017 because separatist fighters had occupied her school and increased their threats against teachers and students. While moving to Yaoundé to continue her education in January 2018, separatist fighters targeted her:

I rented a motorbike with a driver to go to Yaoundé and on my way to Yaoundé, in Mangu, four amba boys armed with guns stopped the motorbike, searched my bag, and found my school documents, including my school card, my [General Certificate of Education Examination Ordinary Level], and my books. They snatched and ripped them up in front of me. They said that they did not want to see any such documents around…. They said all schools should be closed and if they saw me again with my school materials, they would harm me.[109]

Public University Student Kidnapped and Threatened, Njinikejem (December 2018)

Carl, a 24-year-old former University of Bamenda student, said armed separatists who identified themselves as fighters from the group SOCADEF kidnapped, threatened, and tried to recruit him in Njinikejem. They held him in their camp for three days. He believed separatist fighters targeted him not only because of his studies, but also because his uncle is a government official.[110]

Less than a month later, on January 2, 2019, four SOCADEF fighters went to his house, did not find him, and threatened his mother. Carl said, “She told me that they left a very clear message that if I didn’t join their group, there would be consequences.” For his safety and because he wanted to study, he and his mother decided he needed to leave Cameroon.[111]

Public High School Student Threatened, Bamenda (February 2019)

Sam, now 15, described how three separatist fighters with guns and knives stopped him on his way back from school, the Government Bilingual High School Bamenda:

I was walking home from school alone when the amba boys stopped me at around 4 p.m. and threatened to cut off parts of my body if they ever saw me going to school. They pushed me with their motorbike.…. Although I was dressed in plain clothes at the time, not wearing my school uniform for safety, I was caught. I was surprised that they knew I was a student. In fact, I did not even have my school bag…. The amba boys said that if I dared again violate their orders not to go to school, they would come for me and my family. They said they were giving me a last warning. They said that schools should be shut, that they were fighting for us. “We are in the bush fighting for you and you go to school, how do you dare?” they said.[112]

Public High School Student Kidnapped and Tortured, Bamenda (March 2019)

Six separatist fighters who had guns and said they belonged to the group known as 7Kata, kidnapped an 18-year-old student on his way to the Government Bilingual High School Bamenda. He said they took him to their camp, tied him up, tortured him, and held him captive for four days:

I was on my way to school dressed in plainclothes…. I realized a group of amba boys were behind me, so I started running. They caught me. They warned me at gunpoint that if I moved a single step, I will be shot. They asked me, “Where are you going? Where’s your bag?” If I told them I was going to school, they would shoot me. So, I said I was just walking. But they told me they knew I was going to school. They said I am not supposed to go to school while they fight. “All schools should to be shut down,” they said. I finally showed them my bag. They found my books and my school uniform in it…. They took me to their camp on a motorbike at a very high speed. They blindfolded me before entering the camp. There, they beat me with machetes and wooden planks on my buttocks and the soles of my feet. They tied me up, my hands and legs from behind, and kept me in that uncomfortable position for three hours.[113]

They released him following a ransom payment of 70,000 CFA ($130), but they first cut off the part of his national identity card bearing Cameroon’s national flag. One of his classmates witnessed the kidnapping but managed to run away.[114]

Three Female Public High School Students Kidnapped and Beaten, Bamenda (November 4, 2019)

Armed separatists kidnapped three female students in Bamenda’s Ntarikon neighborhood on their way home from school. The students, who were 14, 18, and 20 years old at that time, attended Government Bilingual High School Ntamulung, about one kilometer from where they were kidnapped. The armed separatists blindfolded the students, took them to a separatist camp in Ntanka village, and beat them.

Human Rights Watch spoke with one of the students, Maria, her parents,[115] and a witness to the kidnapping.[116] Maria recounted her experience:

At the camp, we were handed over to a group of 10 fighters who asked us why we were going to school, and before we could say a word, they started beating us furiously. They used cutlasses and planks to beat us on our buttocks and under our feet as well as on our thighs and faces. The beating lasted some 30 minutes and left us with bruises on our bodies…. The pain was unbearable. I cried all through the first night in their camp.[117]

The students were released on November 7, 2019, following a ransom payment of 1,130,000 CFA ($2,100).

Nine Public University Students Kidnapped and Beaten, Bamenda (May 20, 2020)

Jim, a 24-year-old University of Bamenda student, said that separatist fighters stormed his university residence in Bambili, Bamenda, and kidnapped him and at least eight other students. Because May 20 commemorates the 1972 presidential decision to abolish the federal system and form one nation state, separatists declared it a ghost town day. Jim said:

It was about 4:30 p.m. when four amba boys, one with a gun, the other three with machetes or knives, came on foot. They stopped all students who were in front of the hostel and threatened us with death. Some bailed their way out with money. Others, like me, who were poor and had no money were kidnapped. So, the amba took about nine of us, including four or five girls. We walked for about three or four hours in the bush.[118]

The armed separatists took the students to two camps, the first of which was an abandoned school, and kicked, slapped, and beat the soles of the students’ feet with machetes. The fighters released the students after five days following ransom payments ranging from 100,000 CFA ($186) to 500,000 CFA ($933).[119]

Private High School Student Threatened and Beaten, Bamenda (October 2020)

Four separatist fighters threatened to kill a 14-year-old student, beating him on his way to Progressive Comprehensive High School. He said:

The amba stopped me and asked to see the contents of my bag. When they found books, they beat me…. They threatened to kill me if I was going to school again. They asked me to roll in the mud and tore all my books. I ran away and sought refuge in a stranger’s house nearby, hiding under the bed for several hours.[120]

A High-school Student Threatened, Bamenda (November 16, 2021)

Three separatist fighters threatened to kidnap a 20-year-old student on his way to the Government Technical High School in Bamenda. He told Human Rights Watch:

Three Amba stopped me along the road. They were armed with guns. They threatened to kidnap me if I did not comply with their demands to stop going to school. I went back home. I am not going to school now.[121]

This incident occurred four days after Christopher Anu, the spokesperson of the Ambazonia Interim Government, a separatist group, announced the renewal of the boycott of all schools across the Anglophone regions, threatening violence against teachers, students, and school owners who violate the boycott.[122] The renewal of the boycott was made following the death of schoolgirl, Brandy Tataw, caused by a police officer in Bamenda on November 12.[123]

Child Recruitment and Use by Armed Separatists

Armed separatists in the Anglophone regions have recruited children into their groups and used them to support their operations.[124] The ongoing violence, separatists’ threats against students and youth, the frustrations caused by military abuses, and the need for survival have all increased schoolchildren’s risk of recruitment by separatist armed groups. While living among separatist fighters, children may experience violence, may be required to participate in stressful initiation and training ceremonies, and may be forced to take dangerous drugs.

However, due to poor documentation and reporting by Cameroonian authorities, as well as verification difficulties faced by both national and international monitors, there are no available figures about how many children are being used by armed separatist groups in the Anglophone regions.

Accounts from people who were kidnapped and taken to separatist camps reveal that children are present inside armed separatist groups. Human Rights Watch also reviewed photographs and video footage showing people who look like children with guns, standing with other older-looking separatist fighters. However, we were unable to determine if these children were students when they were recruited. Due to the difficulties in identifying current, or even former, child soldiers or recruits—who may experience stigma and fear of retaliation—Human Rights Watch did not speak to any for this report.

Some students voluntarily took up arms. One teacher said that after her school in Kombone Bakundu, South-West region shut down in December 2017, several of her former male students, who were under 18 when the school closed, joined armed separatist groups. She fled Kombone Bakundu and has not returned since because, she said:

It’s very risky for me, as well as other teachers, to go back to Kombone, because some of our students joined the amba, so we could be identified and thus kidnapped for ransom, beaten. I cannot tell you exactly how many of my former male high school students joined the amba, but several of them, for sure.[125]

Others Human Rights Watch interviewed observed school-age children in separatist camps. One kidnapped teacher recognized one child who was fighting with the separatist as his former high school student.[126] Boris saw “10 fighters, all very young, with guns, machetes, sticks—some of them were certainly below 18 years old” at a separatist camp.[127] Maria observed not only men and women, but also boys and girls between 10 and 14 years old equipped with guns, knives, cutlasses, slings, and spears.[128] Ida witnessed that, out of approximately 20 fighters, “many were just little boys of 15 years of age or so” participating in training and ritual ceremonies.[129] In another camp, Veronica saw a 15 or 16-year-old boy among the eight fighters there.[130]

Killing of a schoolgirl by a gendarme (Buea, October 14, 2021)

Caro Louise Ndialle, a 4-year-old girl, was killed by a bullet fired by a gendarme, as she was sitting in a vehicle on her way to school in Buea’s Molyko neighborhood, South-West region. An angry mob responded to the killing by lynching the gendarme.[131]

In a press release issued on the same day, Colonel Cyrille Serge Atonfack Guemo, the army spokesperson, said gendarmes at a checkpoint stopped the vehicle Caro Louise was travelling in, but the driver refused to comply.[132] “In an inappropriate reaction […] one of the gendarmes will fire warning shots in order to immobilize the vehicle,” the press release stated, adding that “in the process” Caro Louise “was fatally shot in the head.”[133] Atonfack also said in the press release that an investigation has been opened by the local administrative authorities and the defense and security forces “to shed more light on and establish responsibilities” in this incident.[134]

Killing of a schoolgirl by a police officer (Bamenda, November 12, 2021)

Brandy Tataw, an 8-year-old schoolgirl, was killed by a bullet fired by a police officer as she was walking down a road in Bamenda, North-West region, on her way back from school.

In a November 12 news release, Martin Mbarga Nguele, the national security delegate general and Cameroonian police chief, said that Tataw was hit as she was walking down the street by a ricochet bullet a policeman had fired at a car that failed to stop at a police checkpoint.[135] Nguele also announced that an investigation had been opened into the killing of Tataw and that the policeman believed to have fired the shot had been arrested.

The killing of Tataw sparked protests in Bamenda, where hundreds of people took to the streets calling for justice for the police killing of the child. Cameroonian soldiers used excessive and lethal force, including live bullets, to disperse the protesters, injuring at least seven of them.[136]

IV. Attacks on Teachers by Armed Separatists

When [the separatist fighters] were torturing me because of my profession, I thought that they were attacking the whole sector. I am not just one victim—it’s the education sector which is under attack.

– Andrew, a teacher who was beaten and shot by separatist fighters, April 2021[137]

At least 100 education professionals have been attacked by separatist fighters since 2017, according to reports by the UN and other credible organizations, as well as Human Rights Watch research. Human Rights Watch has documented in detail 12 attacks against teachers, principals, school staff, and other education professionals. These attacks have included killings, physical assaults, kidnappings, extortion, threats, and other forms of intimidation.

Teachers Human Rights Watch interviewed believed their attackers were separatist fighters because of their clothing (plainclothes or just military pants or camouflage t-shirts as opposed to full uniforms), accessories (including amulets), types of weapons (such as hunting guns and machetes), language (Pidgin English, English, and local dialects), and statements accusing educators of teaching (including by saying teaching is a crime) and saying that schools should be closed. Finally, when kidnappings occurred, the perpetrators took their victims to camps in often remote areas—as opposed to police, gendarmerie, or military stations or barracks—one of the common tactics used by armed separatists.

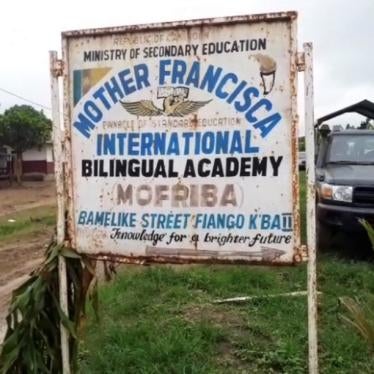

Public school teachers, being government workers, appear to be the main targets of separatist fighters. However, Human Rights Watch also documented separatist fighters’ attacks on teachers at private schools, such as at Kulu Memorial College and the Mother Francisca International Bilingual Academy.

Attacks in the South-West Region

Owner of Private Community School Kidnapped and Beaten, Muea (July 17, 2018)

Separatist fighters kidnapped the owner of the Community Christian College.[138] They identified themselves as separatist fighters, accused him of teaching and not respecting the boycott order, took him to their camp, and slapped his face before releasing him four days later after a ransom payment of 1 million CFA (US$1,866). Separatist fighters had already harassed him and extorted food and 80,000 CFA ($149) from him in a previous encounter. “They said that I had to support their struggle for independence and help them buy weapons,” he said.[139]

Public School Head Teacher Cut with a Machete, Bachuo Ntai (March 16, 2019)

Four separatist fighters came to the house of Clara, the head teacher at a government nursery school in Bachou Akagbei village, at about 8 p.m. They said they were separatist fighters, accused her of teaching, and ordered her to stop. She gave them 30,000 CFA ($56) when they demanded “their own share of the government money [she] was receiving as a salary.” They then cut her with a machete all over: on her back, neck, elbow, and hands, almost completely chopping off her right hand, which she later had amputated.[140] The teacher’s neighbor rushed to the scene right after the assault and took her to a hospital for treatment.[141]

According to Clara and one of her neighbors, security forces arrested at least one perpetrator and identified him as a separatist fighter. He is held at the Buea central prison while his trial is ongoing at time of writing.[142]

Clara has not been able to resume teaching as she is physically incapacitated and feels psychologically down. She also expressed concern for her children, particularly her 19-year-old daughter who witnessed the incident.[143]

Private School Teacher Cut with Machetes, Moko (June 12, 2019)

Seven separatists, some with machetes and others with guns, broke into the home of Aster, a 31-year-old teacher at about 4 a.m., and assaulted her for committing the “crime” of teaching. “I tried to beg them, but they did not show mercy and cut my right leg with machetes before running away,” she said. She later had her leg amputated at a hospital in Douala, more than 50 kilometers away.[144] Three others corroborated the victim’s account, and Human Rights Watch reviewed a photograph taken by one of the victim’s relatives showing her almost completely severed and bleeding leg.[145]

17 Government Teachers Kidnapped and Beaten, Mundemba Camp (August 31, 2019)

Separatist fighters kidnapped 17 teachers, including 11 women, at about 8 p.m. while the teachers were heading to a meeting organized by the school administration.[146] The armed separatists beat the teachers before releasing them at about 3 a.m. on September 1, 2019. One teacher, Boris, recounted his experience:

At least five amba boys armed with guns intercepted us and took us to their camp some three kilometers away. We found more fighters there. They accused us of going to school and keep[ing] schools open, while they have given instructions that all schools should be shut down. They said they had to punish us and that we had to pay a ransom to be released. We were asked to lay on the ground where they beat us with canes, sticks, cables, and machetes. Women were also beaten. Some were bleeding…. They took all the money we had and then let us go.[147]

Public University Teacher Killed, Bamenda (May 17, 2020)

Two separatist fighters killed a 58-year-old University of Bamenda teacher, Paulinus Song,[148] who they had previously threatened and accused of being a traitor for not complying with their school boycott. When the teacher told the separatists that he needed to teach to make a living, they demanded 500,00 CFA (US$933), but he could not afford to pay.[149]

A witness to the killing said:

I saw two amba boys on a motorbike approaching him in front of his home. I was standing nearby. They said to him, “You are stubborn. Your end has come,” and then, they shot him once in the head and twice in the chest. He fell on the ground in a pool of blood. It was in broad daylight. I was terrified. He died on the spot. No one called the police [out of fear].[150]

Public School Teacher Kidnapped and Beaten, Bafia (August 5, 2020)

Separatist fighters, who said they were from a group known as “Mountain Lions,” kidnapped a teacher from his home at 7:30 a.m., for refusing to hoist the “Ambazonia” flag outside his community school. At their camp, he said he found 16 other hostages, including other teachers and parents of students. They beat the soles of his feet with machetes for the three consecutive days and hit his arms and back. About a month later, on September 3, they released him following a ransom payment of 300,000 CFA (US$560), which he needed to borrow.[151]