The Covid-19 pandemic has exposed the difficult economic and social realities for many working people in the United States and has exacerbated pre-existing inequalities. Low-wage workers, who are disproportionately women, migrants, and Black, Indigenous, and other people of color, have largely borne the brunt of the pandemic’s economic fallout.

Weaknesses and deficiencies in US labor law have made the situation worse. Workers face major obstacles to organize, unionize, and collectively bargain for fair wages, decent benefits, and safe working conditions. On numerous fronts, US laws fall far short of international standards on freedom of association and collective bargaining.

Now there is an opportunity to strengthen US labor laws. The Protecting the Right to Organize Act (the PRO Act), H.R. 842, S. 420 passed the US House of Representatives on March 9, 2021 with a bipartisan vote. If approved by the Senate, it would significantly strengthen the ability of workers in the private sector to form unions and engage in collective bargaining for better working conditions and fair wages. If enacted into law, the PRO Act would be the most comprehensive worker empowerment legislation since the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) of 1935.

This question-and-answer document addresses the PRO Act through a human rights lens, with a focus on the right to freedom of association and collective bargaining. It examines the challenges of unionizing in the US and explains how the PRO Act would be a corrective. Current US law excludes certain categories of workers, makes it difficult for workers to join unions, hampers the fight for better working conditions, and has failed to keep up with the disruptive role of workplace technologies in organizing efforts. Addressing these shortcomings could help to bring US law closer to international human rights standards, and slow or reverse decades of rising economic inequality.

Part I: Human Rights Standards

Is there a human right to unionize and to bargain collectively?

How does the right to organize affect economic and social inequality?

Does current US federal law meet international standards on the right to organize?

Part II: Unionizing in the United States

What is the state of union membership in the United States?

How does the US compare with other high-income countries on union membership?

Why is US union membership so low?

How is technology affecting the way workers organize?

How can technology make it easier for employers to suppress or discourage organizing?

Part III: The Protecting the Right to Organize Act (PRO Act)

What is the PRO Act and how could it address existing deficiencies in US law?

What protections do workers lack, and how would the PRO Act expand the right to organize?

What about app-based “gig” workers?

How would the PRO Act protect the right to strike?

How else would the PRO Act strengthen unions?

How does the PRO Act protect digital organizing?

How does the PRO Act harness technology to support free and fair union elections?

Does the PRO Act offer remedies for violations of the rights to collectively bargain and unionize?

Can employers continue to make workers waive lawsuits to exercise their rights?

What other policy solutions are needed to strengthen workers’ ability to form and join unions?

Part I: Human Rights Standards

Is there a human right to unionize and to bargain collectively?

Yes. International human rights law is clear that governments have an obligation to ensure that everyone has the right to organize for better working conditions, to form and join unions, to strike, and to bargain collectively with employers.

Article 22 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which the United States ratified in 1992, recognizes the “right to freedom of association with others, including the right to form and join trade unions for the protection of his interests.” Article 8 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) also recognizes and elaborates on these rights. The United States has signed, though not ratified, the ICESCR, but it has a duty to refrain from actions that would defeat the object and purpose of the covenant.

The right to unionize is also protected by the Fundamental Conventions of the International Labour Organization (ILO)—in particular Convention No. 87 on Freedom of Association and the Protection of the Right to Organize and Convention No. 98 on the Right to Organize and Collective Bargaining. The United States is an ILO member and has a duty to abide by these conventions’ terms, even though it has not ratified them. The ILO also considers the right to strike to be an “intrinsic corollary” of the right to freedom of association if it is utilized as a means of defending workers’ economic and social interests. It also has said that the right to strike is one of the “essential means” for workers to improve their working conditions.

How does the right to organize affect economic and social inequality?

Protecting the rights to organize and bargain collectively can play a key role in reducing economic and social inequality. These rights allow workers to stand together and bargain for fair wages, adequate benefits, and safe working conditions, and they protect against unjustified job loss and discriminatory or unfair employer behavior, which can help to narrow the racial and gender wage gap.

Many policymakers and commentators have long promoted hard work and academic success as primary tools for overcoming a precarious economic existence, but research published in 2018 for the National Bureau of Economic Research in the US shows that this approach overemphasizes the ability of individuals to pull themselves up by their bootstraps and neglects the many structural barriers that limit economic opportunity or keep people trapped in poverty. Labor movements and unions are tools of workers to overcome these barriers collectively and to address power imbalances between workers and employers in a labor market. They can also play a critical role in tempering exploitation through monopsony, a situation in which a few powerful employers depress workers’ wages by dominating the labor market.

Protecting the right to organize may also limit the corporate capture of public institutions. Companies regularly lobby and pressure legislatures, policymakers and government agencies to weaken workers’ rights protections that the companies perceive to be detrimental to their business interests. The collective power of unions and other labor groups serves as a critical check on this influence. In a 2019 study, researchers at Duke University and the University of Toulouse found that where unions are weaker, politicians tend to be less responsive to the preferences of low-income earners and more attentive to the interests of the elites. Participation in unions also appears to promote voter participation in elections.

Does current US federal law meet international standards on the right to organize?

No. While US law formally guarantees workers the right to organize, Human Rights Watch and other groups have documented several areas in which federal law fails to adequately protect the freedom of workers to associate and bargain collectively. Considered both separately and collectively, these various deficiencies in federal law lead to a situation in which internationally protected workers’ rights are violated in the US.

Separate laws regulate unions in the public and private sectors. Union activity in the private sector is principally governed by the 1935 National Labor Relations Act (NLRA). The NLRA also established a federal agency, the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), which has created an extensive set of doctrines regulating labor relations.

Some of the rights failures reflect issues with the NLRA itself and the court decisions interpreting it. Others are due to various NLRB decisions that have also failed to protect the right to form unions. Because the political and ideological composition of the NLRB can change frequently, particularly from one White House administration to another, its rules frequently change depending on the president who appointed a majority of board members. This uncertainty signals the need for Congress to step in and codify workers’ protections in legislation.

Part II: Unionizing in the United States

What is the state of union membership in the United States?

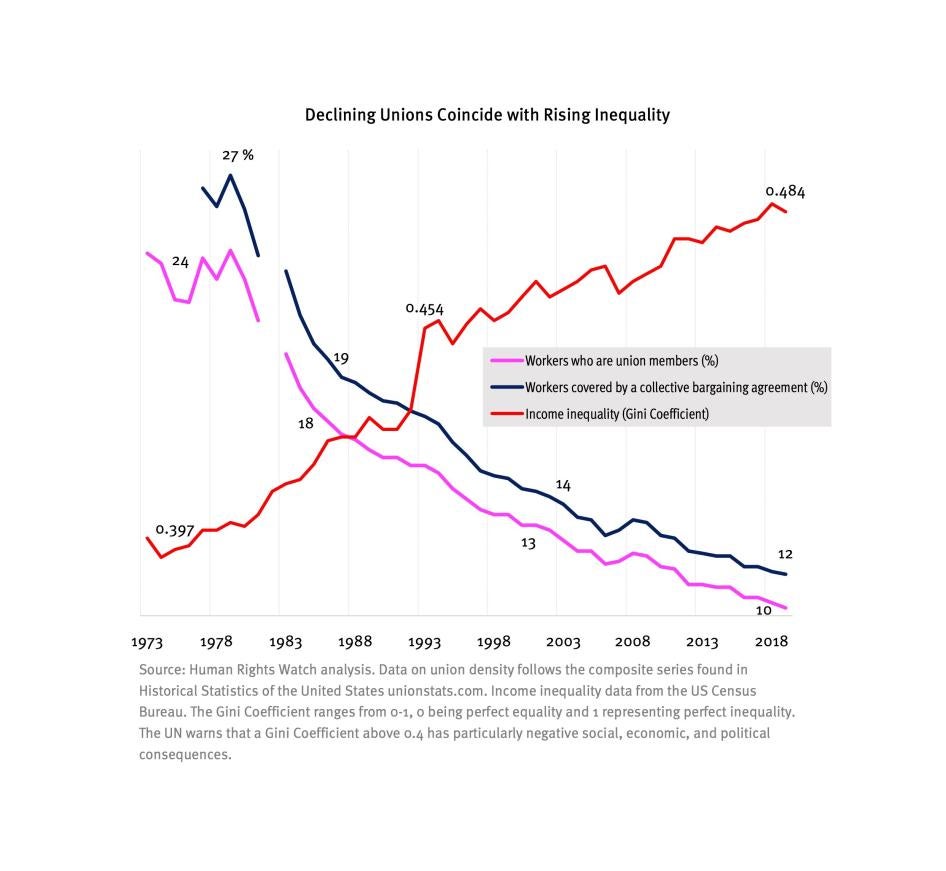

In 2020, after a period of steady decline, union membership (the share of workers who are members of a union, also referred to as union density) in the United States stood at a very low 10.8 percent. The share of US workers with collective bargaining coverage (those represented by a union, including nonunion members) was similarly low, at 12.1 percent. Union membership was significantly higher in the 1950s through the 1970s with about a third of workers being part of, or protected by, a union, but after 1973, union membership in the private sector became the target of antiworker politicians and corporations.

Historical data show that the decline in bargaining power coincided with stagnating wages for lower income workers and growing income inequality. Researchers at Harvard University and the University of Washington found that the drop in union density may have accounted for as much as 40 percent of rising inequality.

Presently, a worker covered by a collective bargaining agreement in the United States on average earns about 11.2 percent more than a worker with a similar education, occupation, and experience in a nonunionized workplace in the same sector. This difference is more pronounced for Black and Hispanic workers, which suggests that unions can help to reduce the racial wage gap. On average, Black workers represented by a union earn 13.7 percent more than their nonunionized peers, and Hispanic workers represented by a union earn 20.1 percent more.

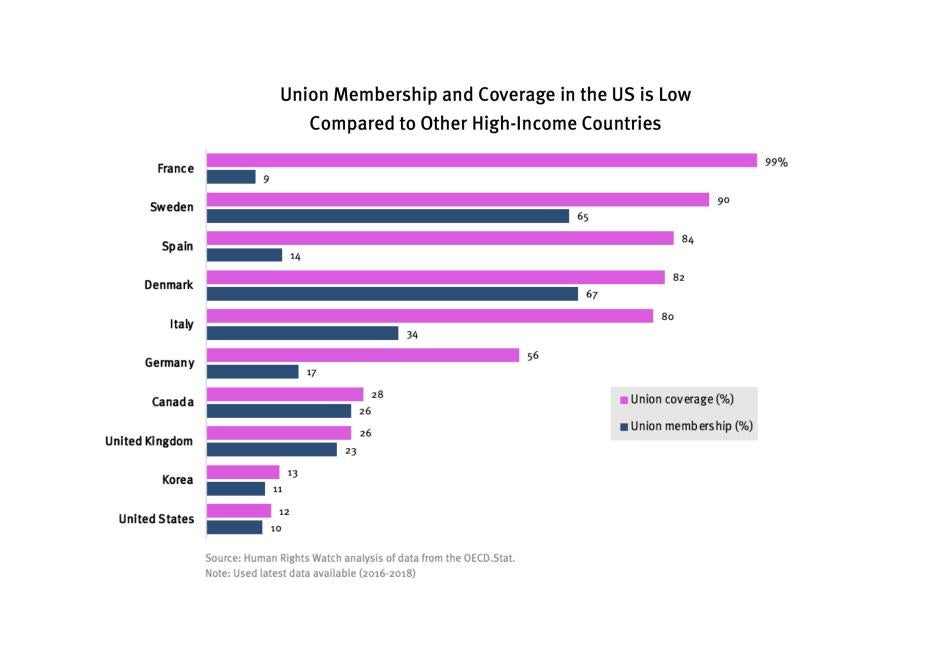

How does the US compare with other high-income countries on union membership?

The US has a relatively low share of union membership compared with other high-income countries (member states of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, or OECD). More notably, there are striking differences among countries’ membership rates and union coverage, meaning the share of workers who are not union members but are represented by unions. In the United States, a worker might not be a member of a union but may still be covered by a collective bargaining agreement—by law a union must represent all workers at a firm, even those who decline to join the union. But some other countries utilize sectoral or national bargaining, in which a union negotiates an industry-wide collective bargaining agreement with all employers in a given sector, or in the case of national bargaining, across various sectors. Such systems cover workers even if no contract was negotiated with that worker’s individual employer.

In the United States, 12.1 percent of workers are represented by a union; in France, the share is 98.5 percent; in Sweden, 90 percent; in Spain, 84 percent; and in Denmark, 82 percent. Levels of union coverage observed in these countries result, in large part, from less restrictive legal frameworks and, in some cases, from the involvement of unions in the administration of social benefits, such as unemployment insurance.

Why is US union membership so low?

A variety of factors have contributed to the decline in union membership in the US. One significant reason is the substantial impediments workers face when trying to exercise their rights to organize and bargain collectively. US law allows employers to stifle organizing efforts in numerous ways and imposes few meaningful penalties when they violate the law. Employers are often hostile toward union activity and have developed a variety of strategies to resist union organizing drives, including hiring special union avoidance consultants.

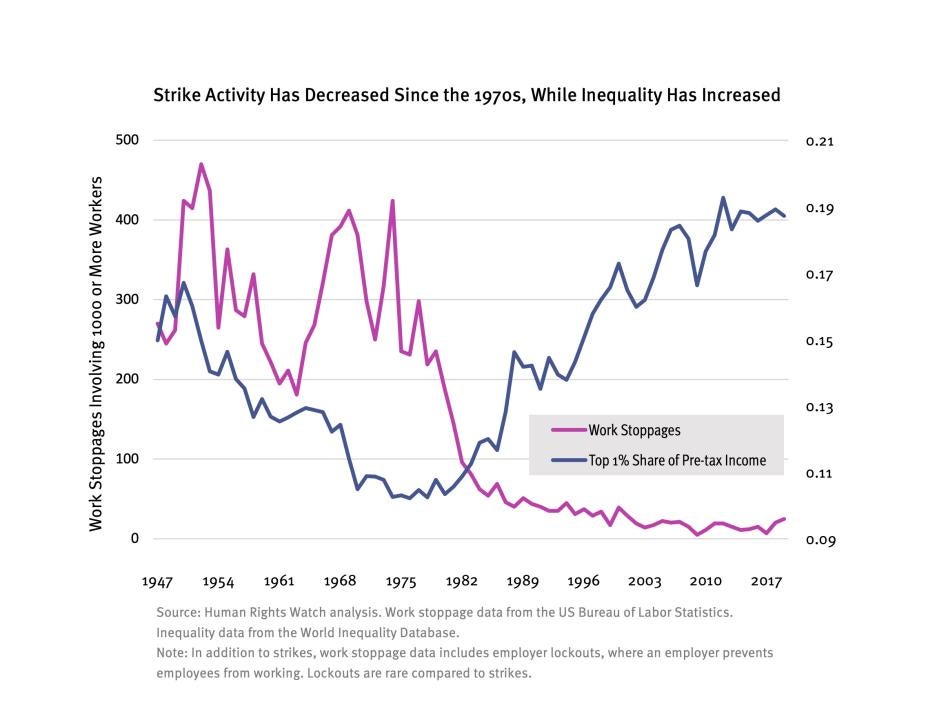

The Economic Policy Institute found that charges against employers for allegedly violating federal labor law were filed in over 41 percent of union election campaigns in 2016 and 2017. Since the late 1970s, especially after President Ronald Reagan fired and replaced striking federal air traffic controllers in 1981, employers have become increasingly aggressive in their efforts to break strikes and weaken unions.

Another key reason for union membership’s decline is the fragmentation of the labor market known as “fissuring,” in which big companies subcontract and outsource work previously done in-house (such as janitorial services) to save costs. These companies often exert their market power to suppress the prices of supplier firms, which in turn incentivizes contractors to keep wages low and provides little job security. This dynamic erodes the formal worker-employer relationship and makes it more difficult to organize. A fissured labor market also exacerbates racial and gender inequality, as Black, Indigenous, and other people of color, noncitizens, and women are often disproportionately represented in low-wage and fissured sectors.

The growth of app-based companies after the Great Recession of 2007 and 2008 has exacerbated workplace fissuring in the United States. These companies use algorithms and other data-driven technologies to match consumers with workers who provide a wide range of services, such as transportation, grocery delivery, care work, and repairs. Many of these companies also deploy technologies to exercise extensive control over how, when, and where their employees work, and how much they are paid.

But companies routinely claim that they are merely technology platforms and they wrongly classify their workers as independent contractors, an employment category with few wage and labor rights protections and no recognized right in the US to bargain collectively or unionize. The result is that workers for app-based companies often struggle to attain an adequate standard of living.

This tech-enabled strategy of misclassification threatens to spread and disrupt workers across all industries, incentivizing employers in other sectors to “gig out” jobs and shift the jobs of one-time employees to precarious workers without basic labor rights and safety nets.

How is technology affecting the way workers organize?

The dispersed and precarious nature of app-based work is also disrupting how workers organize. Physical workplaces have traditionally played a key role in organizing, enabling workers to forge relationships of solidarity and trust through the shared experience of working in the same location over time. In contrast, app-based workers lack a common workplace and they take individualized routes depending on the work requests they accept. This isolation is exacerbated by high turnover, which impedes the ability and incentive for workers to invest time in organizing.

Despite these challenges, workers are developing other ways to connect and organize, such as online forums, email, social media groups, and messaging apps to discuss grievances and mobilize support. App-based workers have used these platforms to coordinate digital walkouts, collectively logging off and refusing to accept ride or delivery requests during designated times.

Office workers across a variety of sectors also rely on internal communications tools, such as mailing lists and chat rooms, to organize open letters, petitions and walkouts. The Covid-19 pandemic may accelerate the shift toward digital organizing, as more workers transition to remote work. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, almost one in four workers performed their jobs remotely in August 2020 because of the pandemic.

How can technology make it easier for employers to suppress or discourage organizing?

Online organizing efforts are vulnerable to digital censorship, intrusive surveillance, and employer retaliation. Absent strong federal or state protections against workplace surveillance, US employers have wide latitude to monitor and moderate company emails, message boards, and other internal communications. Employers that host Facebook groups for workers have deleted posts criticizing workplace conditions, while others have established moderation policies on email listservs that restrict discussions about workplace representation.

A growing number of employers are also installing monitoring software on their employees’ work devices to record online activities, including email, web browsing histories, and even keystrokes, which could expose plans to organize or unionize. Surveillance tactics have infiltrated the public domain, with some employers monitoring social media groups set up by workers to keep tabs on efforts to organize, protest, or strike.

Current US law also allows employers broad leeway to spread anti-organizing messages through one-on-one conversations, emails, and “captive audience” meetings—compulsory meetings, held under threat of discharge, in which employers discourage workers from unionizing. The tech-savvy campaign behind Proposition 22, a corporate-funded ballot initiative in California that eviscerated state labor laws protecting app-based workers, shows how employers can leverage access to technology and data to promote their own messaging to workers, or enlist them in campaigns that are unrelated to their work and may run counter to their interests, in ways that could also undermine organizing:

- In the lead up to the vote, Uber sent pop-up notifications requiring drivers to support or acknowledge Prop 22’s benefits while logged on to their app—a measure akin to a “captive audience” tactic that sparked complaints from drivers. The company subsequently modified the notifications to make them “more informational,” and gave drivers the option to close the notification.

- Instacart sent in-app notifications to select shoppers asking them to retrieve Yes on Prop 22 stickers from a grocery store in the Bay Area and “place it in your customer's order." Although Instacart told Human Rights Watch that this activity was “completely voluntary,” the notification did not provide shoppers an opt-out. Instead, the notification required shoppers to report whether the stickers were “found” or “not found.” Instacart said they did not retain data on which shoppers included the inserts in their deliveries.

- Doordash emailed restaurants and other merchants offering them free “Yes on 22” takeaway bags and encouraged them to use the bags in the lead-up to Election Day. Doordash told Human Rights Watch that, as part of this program, “several hundred merchants requested millions of bags, and the bags only went to merchants that requested them, who were eager to use them.” Delivery workers making deliveries for these merchants had little choice but to distribute pro-Prop 22 campaign materials even if they did not support the initiative.

Part III: The Protecting the Right to Organize Act (PRO Act)

What is the PRO Act and how could it address existing deficiencies in US law?

The Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act is a labor law and civil rights reform, and an economic stimulus proposal. On March 9, 2021, the US House of Representatives passed the PRO Act on a bipartisan vote, 225 to 206. The PRO Act would expand protections for workers to exercise their rights to join a union and bargain collectively for better wages and working conditions.

The PRO Act would bring US law closer to international standards by addressing many barriers that workers face when trying to unionize. It would also address important structural policy barriers that keep workers from joining unions and would support the labor movement’s efforts to push back on rising income inequality.

What protections do workers lack, and how would the PRO Act expand the right to organize?

The PRO Act would eliminate many of the existing loopholes in US law that undermine organizing.

The NLRA currently does not protect low-level supervisors and managers from anti-union discrimination, nor does it give them the right to unionize. It also excludes independent contractors, even if employers exert the same kind of control over them that they would exert over employees. By narrowing the definition of “supervisor” and clarifying the definition of “employee,” the PRO Act would help to remedy these exclusions, protecting the right of these workers to organize without fear of retaliation.

The PRO Act would also give undocumented workers full relief if their labor rights are violated, reversing the Supreme Court’s decision in Hoffman Plastic Compounds, Inc. v. NLRB. The court in Hoffman Plastic held that undocumented workers are not entitled to back pay if they are illegally fired—or deported—in retaliation for organizing, leaving these workers extremely vulnerable to employer retaliation for exercising their rights.

In addition, the PRO Act would strengthen rules regarding “joint employers,” in which two companies both exert control over an employee’s working conditions (a common feature in an increasingly fissured economy).

When companies are considered joint employers, they both have an obligation to bargain with employees over working conditions that they control or influence and can be held liable for violating their employees’ rights under the NLRA. But the current NLRB standard for finding a joint employer relationship is too lax, potentially causing workers to be unable to bargain with the company that effectively controls their working conditions. And that company could escape liability for violating the workers’ rights. The PRO Act would restore and codify the more rights-protective joint employer standard in place during the administration of former President Barack Obama, allowing a company’s “indirect control” over working conditions to be sufficient for finding joint employer status.

What about app-based “gig” workers?

The PRO Act would clarify the definition of “employees” covered by NLRA protections to include app-based workers. For purposes of the NLRA, the PRO Act defines an independent contractor as: a) free from control and direction in performing a service, both under the contract and in fact; b) performing the service outside the employer’s usual course of business; and c) customarily engaged in an independently established business to provide the service. Many states also use this “ABC” test to ensure that workers are covered by their wage and hour laws, unemployment insurance system, or other employment laws, regardless of what their employer calls them. If the same test is applied to the NLRA, it could extend bargaining protections to at least 1.9 million workers in the app-based economy.

The PRO Act would only recognize app-based workers as employees for the purposes of organizing and unionizing but would not provide them with other key labor protections, such as the minimum wage or paid sick leave.

How would the PRO Act protect the right to strike?

Under the PRO Act, workers would no longer be forced to put their jobs on the line to strike over unfair wages or benefits (also known as “economic strikes”). While current US law prohibits employers from firing workers who participate in these strikes, it permits employers to undermine this protection by “permanently replacing” strikers with other workers. This means that, even after a strike ends, strikers cannot return to their jobs unless their replacements leave. The US is one of a handful of countries that gives companies such broad authority to hire permanent strikebreakers, a practice that, in most cases, the ILO Committee on Freedom of Association considers a “serious violation of freedom of association.” By prohibiting the use or threat to use permanent replacements, the PRO Act would make it harder for employers to break strikes or convince workers that unionizing would be futile.

The PRO Act would also remove the existing bar on participating in “sympathy strikes” or “secondary boycotts,” in which workers strike over conditions at another workplace or pressure companies to stop doing business with their direct employer. These activities are almost entirely prohibited under current US law, in violation of ILO standards. By repealing the prohibition on secondary actions, the PRO Act gives workers more power to address the impacts of fissuring by holding increasingly interconnected companies accountable for poor working conditions.

How else would the PRO Act strengthen unions?

The PRO Act would override so-called “right-to-work” laws, which many states have passed, especially in the southern US. These laws prohibit “fair share agreements” that require all employees in a bargaining unit to contribute dues to the union representing them. Instead, these laws allow employees to opt out of paying dues, even though the union is obligated to represent all employees in collective bargaining and grievance proceedings, regardless of whether they are members.

Right to work laws are a vestige of the Jim Crow era and are steeped in a history of racism. These laws, originally created in the 1940s to keep Black and white workers apart and to preserve the US south’s racial and economic hierarchies, have been promoted by a network of billionaires and special-interest groups to weaken workers’ collective voice on the job and give more power to corporations. Right to work laws not only weaken unions but are also associated with lower wages, even after controlling for other variables.

How does the PRO Act protect digital organizing?

The PRO Act would establish the “right to use electronic communication devices and systems” provided by the employer to engage in collective bargaining and unionizing activities, unless there is a “compelling business rationale denying or limiting such use.” This would prevent employers from unduly censoring discussions on internal communications systems about collective action.

It also would open the door to rulemaking to protect collective action from the growing presence and reach of workplace surveillance technologies. Under existing law, the NLRB has deemed employer surveillance unlawful when it amounts to “out of the ordinary” behavior to monitor union activity. But this limited check does not address how workplace surveillance ostensibly rolled out for business purposes, such as behavioral detection cameras and productivity monitoring software, may deter, chill, or interfere with collective action.

The PRO Act would also prohibit employers from “requir[ing] or coerc[ing] an employee to attend or participate in such employer’s campaign activities unrelated to the employee’s job duties.” In addition to banning “captive audience” meetings, this provision would increase scrutiny of how employers use technology to enlist worker support for anti-organizing or other activities that may run counter to workers’ interests.

Finally, the PRO Act would require employers to disseminate electronic notices about workers’ rights to unionize and self-organize. While this will help establish baseline awareness about workplace representation, effective guidance is needed to ensure that employers convey this information in a clear and accessible format.

How does the PRO Act harness technology to support free and fair union elections?

The PRO Act would require employers to provide labor organizations with the contact information of employees eligible to vote for representation, including their email addresses, cell and home phone numbers, and home addresses. This requirement preempts a NLRB proposal to eliminate email addresses and phone numbers from voter lists. Many workers—including app-based workers who are frequently on the road—are not easily reachable at their home address. Providing organizers with phone numbers and email addresses will enable them to convey timely updates about workers’ rights to vote and engage with workers about issues of representation wherever they are. To mitigate privacy concerns, the NLRB limits the distribution of voter lists to organizations seeking to represent workers and requires them to use such information only for representation matters.

The PRO Act would also direct the NLRB to implement electronic voting systems that enable employees to vote in a representation election over the internet or the phone. Unions have urged the rollout of electronic voting to mitigate the personal safety and public health risks of voting in person during the Covid-19 pandemic. Electronic voting may also improve access to union elections, particularly among remote, geographically dispersed, and app-based workers. Requiring the NLRB to implement electronic voting would be a step in the right direction. But the government should also ensure that the board has adequate resources to manage this complex undertaking, which requires robust standards for voter secrecy, accessibility, election monitoring and digital security.

In addition to modernizing union elections, the PRO Act would make it harder for companies to use the delays leading up to union elections to mount anti-union campaigns. The PRO Act would speed up elections by allowing workers and the NLRB to set voting procedures without employer involvement and by ensuring that pre-election hearings are held promptly.

Does the PRO Act offer remedies for violations of the rights to collectively bargain and unionize?

The US has no civil penalties for employers who violate the NLRA by engaging in anti-union conduct. In some cases, employers may be required to post a notice that they violated the law but are not otherwise penalized. Under current US law, when workers are fired for union organizing they are only entitled to be rehired with back pay minus any amount they could have earned elsewhere in the interim—a remedy so weak that companies can treat it as a mere cost of doing business.

Undocumented workers are denied even this meager relief. Moreover, employees have no private right of action to enforce their rights. Only the NLRB can prosecute violations of federal labor law. However, the board’s rulings are not self-enforcing, and the board has to petition a federal court of appeals for enforcement if an employer does not comply. Such procedural hurdles mean that workers often wait years for relief.

The PRO Act would give workers full back pay, without any reduction for interim earnings, as well as damages, and extends this relief to undocumented workers. The act would also establish meaningful civil penalties for employers who violate federal labor law and makes NLRB orders self-enforcing. It would provide employees, including undocumented workers, with a private right of action if the NLRB does not prosecute their case.

It would also require the NLRB to take immediate action to stop employers who commit serious violations of the NLRA from continuing those practices, providing crucial preliminary relief to affected workers, including preliminary reinstatement of workers fired for union activity, through a court order. Finally, if the NLRB determined that an employer interfered with a formal union election, preventing a free and fair election, the PRO Act would allow it to certify the union and require the employer to engage in collective bargaining if a majority of employees had previously signed cards authorizing the union to represent them.

Can employers continue to make workers waive lawsuits to exercise their rights?

No. Under current law, employers can require workers to sign contracts that prohibit lawsuits against them. The Economic Policy Institute has found that arbitration proceedings “overwhelmingly favor” employers. The PRO Act bans agreements that would prevent employees from pursuing class action lawsuits and collective claims against their employers for employment-related matters, such as wage theft, workers’ compensation, harassment, and discrimination.

Based on an analysis conducted by Rideshare Drivers United, six major app-based companies require workers to accept terms of service agreements that limit the resolution of most work-related disputes to arbitration by default. Workers are given 30 days to opt out from arbitration from the date they consent to the agreement. According to Rideshare Drivers United, many drivers are not aware of the arbitration clause and its impact on their rights. The clause is buried in lengthy terms of service documents and uses legal language that is often inaccessible to workers. Some drivers only become aware of the significance of the arbitration clause when it is too late, such as when they try to organize other drivers to file a class action lawsuit.

What other policy solutions are needed to strengthen workers’ ability to form and join unions?

The PRO Act would bring the United States closer into compliance with international norms by remedying many problematic provisions of current law that both collectively and individually violate workers’ rights to freedom of association and collective bargaining. By bringing the US more in line with international standards on workers’ rights, the PRO Act would strengthen the ability of workers in the private sector to join and form unions and to fight for better working conditions and fair wages. This, in turn, could help address the high and increasing levels of wage inequality in the US.

Passage of the PRO Act would be a significant step forward, but it is not the only action needed. The US government should further amend the NLRA to include agricultural and domestic workers, who are exempted from its protections and who often face abusive working conditions. These workers are only covered by a patchwork of state-level protections. Further reforms to the US visa system are also needed to improve protections for noncitizen workers, regardless of immigration status, from abusive employer practices. Public sector workers also need comprehensive state and federal protections, because they are not covered by the NLRA and are often subject to restrictive state laws that contravene international standards.

While the PRO Act would offer a critical bulwark against the misuse of workplace technologies to undermine collective action, US workers need more comprehensive reforms. App-based workers, who may still be wrongly considered independent contractors even if the PRO Act passes, require broader federal recognition of their employee status, and other protections such as the minimum wage, paid sick leave, and unemployment insurance. The Biden administration should also enact stronger protections for workers’ privacy, beginning with safeguards that protect organizing activities from undue digital interference.