(Tunis) – Police in several Tunisian governorates appear to have responded to social justice protests in recent weeks with excessive force at times, leaving one man dead and arresting hundreds, including many minors, Human Rights Watch said today.

The authorities should conduct an urgent and transparent investigation into the death of Haykel Rachdi, who died from a serious head injury following police intervention during a protest, on January 18, 2021, and investigate alleged beatings of protesters. They should also be sure only to use teargas in a proportionate matter and to the extent necessary, and release those held solely for peaceful assembly or expression. The authorities should also ensure access to lawyers and humane detention conditions.

“Tunisia’s nationwide protests were triggered by legitimate anger and frustration at the dire economic outlook,” said Eric Goldstein, acting Middle East and North Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “The government should rein in police who have acted unlawfully and ensure the right to peaceful protest and free expression.”

Protests erupted on January 15 after a video posted on Facebook appeared to show a police officer gratuitously humiliating a shepherd in the northwestern governorate of Siliana. The protests – at times violent – erupted in the central region of Kasserine, then Sidi Bouzid, and within days spread to Bizerte, Tebourba, and Sousse, as well as marginalized neighborhoods in Tunis.

These protests erupted despite a nationwide curfew, from 8 p.m. to 5 a.m., to stem the spread of Covid-19 and have ended as of February 4. While there is a public health interest in preventing large gatherings and in the government enforcing those measures, restrictions on freedom of expression for reasons of public health may not put in jeopardy the right itself.

The Interior Ministry has yet to publicly comment on allegations of police violence. Prime Minister- Hichem Mechichi on January 19 acknowledged that economic and social hardship underlay the protests but said that security forces acted “professionally.”

Human Rights Watch spoke with seven activists, one journalist, a relative of the man who died, and a relative of a detained activist. Researchers reviewed videos and photographs posted on Facebook that appeared to show excessive use of teargas and police beating apparently peaceful protesters.

Interviews with witnesses, news reports, and footage Human Rights Watch reviewed indicate that daytime protests were largely peaceful but that there were violent encounters at night in several cities as protesters blocked roads, burned tires, and threw stones and Molotov cocktails to prevent police from entering neighborhoods. Some protesters also reportedly looted supermarkets. The police fired teargas and arrested hundreds of protesters.

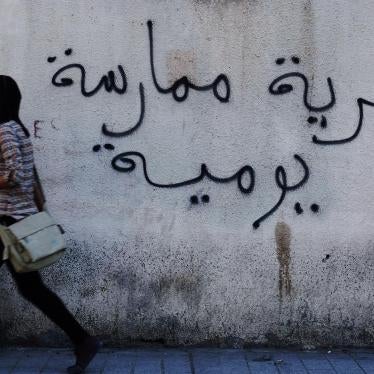

While no group claims to lead the protests, several civil society groups and independent activists called on social media for protests against the economic downturn as well as what they said was rampant corruption and impunity. Some also called for the dissolution of parliament and the government, and an end to police repression. One group published on Facebook a list with demands that included the immediate release of protest-related detainees, establishment of a judicial mechanism for complaints about police violence, a range of financial benefits for disenfranchised groups, and raising of the minimum wage.

Based on interviews and social media posts by activists and corroborating footage, on January 18, 19, and 23, the police, including some in riot gear and with armoured vehicles, used what the activists said were excessive amounts of teargas to disperse peaceful protesters who had gathered in one of the capital’s main streets, Avenue Habib Bourguiba. On January 19, the police, allegedly unprovoked, pepper-sprayed Noureddine Ahmed, a photojournalist, in the face while he was covering the protests.

Another journalist, an accredited member of the media covering the events on January 23, said that police harassed her and another journalist, demanding the footage she had recorded about the arrest of an activist.

Montassar Sellem, an activist, said that during the January 23 protest on Habib Bourguiba Avenue, which was peaceful with no allegations of violence, he witnessed security forces chase protesters, fire teargas, and beat many with batons. On the same day, activists posted on Facebook Live a video from the same protest of a man lying on the ground and apparently bleeding from one side of his face.

“Ever since the protests started, the police have been shooting all kinds of teargas canisters,” said a relative of Rachdi, the man who died after being hit by a teargas canister. “They shoot in the neighborhoods in Kasserine, they fill the houses with smoke.”

Police use of teargas in response to protesters who burned tires and hurled Molotov cocktails may have been proportionate, but its use to disperse a small group of protesters at night in the town of Tebourba on January 19, for example, appeared to be excessive as the teargas permeated residents’ homes and affected families.

Since January 14, police around the country have detained hundreds of protesters, including many minors. An Interior Ministry spokesperson, Khaled Hyouni, said on January 18 that the authorities arrested at least 630 protesters countrywide on that day. He said those detained were between ages 13 and 25.

Saif Ayadi from Damj, the Tunisian Association for Justice and Equality, said that as of January 27, his organization, working with the Tunisian League for Human Rights (LTDH), had identified at least 1,540 people arrested during the protests. According to defense lawyers, he said, the authorities arrested minors without promptly informing their families. At times, he said, police rounded up dozens of protesters, harassed them at police stations, and forced them to sign pre-drafted police reports.

Police violence at protests has been a persistent issue in Tunisia. The authorities have failed to respond with credible and transparent investigations, let alone holding police officers and unit commanders responsible for use of excessive force, Human Rights Watch said.

“Tunisian police have to act decisively to maintain law and order, but they should not suppress free speech and peaceful assembly,” Goldstein said.

Death of Haykel Rachdi

Human Rights Watch spoke with Keddidi Rachdi, a cousin of Haykel Rachdi, a 21-year-old student who died of head injuries after. His family said police fired a teargas canister that hit him during protests in Kasserine on January 18.

Keddidi Rachdi said:

His family first took him to Sbeitla local hospital and then to the Kasserine regional hospital. Two days after he was shot, they organized his transfer to Sahloul hospital in Sousse. He lost consciousness during the transfer. He was in a catastrophic condition. On the way he was already unconscious. He underwent surgery for around four hours. His father told me that upon completion of the surgery, one doctor said his condition was “hopeless” and that the family should not be optimistic. He died on January 25.

He said that the family plans to file a police complaint about the incident. He said the family told him that Farhat Hachad University Hospital in Sahloul, Sousse had prepared a forensic report.

He said that police used excessive teargas even during Hakyel’s funeral:

Ever since the protests started, the police have been shooting all kinds of teargas canisters. They shoot in the neighborhoods in Kasserine, they fill the houses with smoke. The teargas only stopped for two nights after Haykel was shot and then it was back on. At Haykel’s funeral, I saw how police shot teargas directly at people’s legs and bodies to disperse the angry crowd and in anticipation of any protest taking place.

Omri Zouaoui, an activist who attended Haykel’s funeral, confirmed what he said was excessive use of teargas by police:

At around 1 p.m., the family carried the body of Haykel from their house in Cite Essourour to the cemetery and passed by the main road in downtown Sbeitla. I could see at least 60 police cars in the area. Once people in the crowd that accompanied the funeral cortege started to shout and scream denouncing the death of Rachdi, I saw the police start to shoot teargas in an excessive way. I was not directly affected by the teargas.

In the evening, the police used more teargas in different neighborhoods in Sbeitla, especially in Cite Essourour, where Rachdi lived. The area seemed covered with teargas and it affected families, women, the elderly, and children. Young people there were enraged and there was a confrontation between the police and protesters.

Zouaoui said he heard that during the protests more people had bruises on their legs or other parts in their bodies after being hit by teargas canisters.

Arrest for Facebook Post

Bouthaina Louhichie said that the police arrested her son, Ahmed Ghram, a 25-year-old philosophy student, at the family home in the Tunis southern suburbs on January 17. Ghram was acquitted and released on January 28, after 11 days in pretrial detention. Louhichie said she later learned he was arrested for Facebook posts critical of police repression, the governance system, and alleged official corruption and rampant impunity.

She said that the police led her son away without showing an arrest warrant and that officials turned down the family’s request to provide a lawyer to be with him during his interrogation:

Judicial police officers of Mourouj district and the head of Mourouj 3 Police Station came to my house around 4:30 p.m. on January 17. An armada of police cars accompanied them. The head of Mourouj 3 Police Station is from the area, he knows my family, and he is the one who led them to the house. They knocked on the door, and one of my other sons answered. The two officers told my other son to get his brother, who was asleep.

Meanwhile, the two officers told me to get Ahmed’s phone and laptop. I was so naïve and feared they would hurt my son, so I went to get them. I asked them if I should get Ahmed a lawyer and they said, “This isn’t really a big deal, and he will return home in no time.” The police did not say anything specific during the operation. They did not give a reason for his arrest and did not show an arrest warrant. They just told Ahmed to accompany them alone in the police car.

I followed with my own car. Ahmed was in his pajamas and house shoes and was taken like this to the police station. He was not given the time to change his clothes, the police did not permit it. I arrived at the Morouj 3 Police Station within 15 minutes after them, where I asked them again to get him a lawyer, but they went ahead and interrogated him without a lawyer. He was given one copy of the report to read and sign.

The police report that Ghram signed, which Human Rights Watch reviewed, states that “In context of the recent events in the country and the situation that we have observed, we concluded that the detainee has been inciting, on his Facebook page, actions of chaos and disorder.”

The police report mentions at least 10 Facebook posts from a youth group supporting the protests and demanding a new governance system, which Ghram shared on his timeline. According to the report, one of the posts says, “When you steal because you’re hungry and impoverished, they debunk you and call you a criminal, but when you steal the money of the people for years and deny them their wealth, then they call you a businessman and they defend you.” Another post states, “A system that is based on stealing from marginalized classes and workers, based on favoring people and shattering others.... Do you really want people to hold pretty and nice protests?” None of the posts appeared to incite violent protests.

The police report confirms that they confiscated Ghram’s phone, although Louhichie said that the police also confiscated his laptop. The report states that Ghram said he did not need to see a lawyer or have a medical exam upon arrival at the police station, but Louhichie says her son asked for both and was refused. The report lists as evidence screenshots of 9 of his 10 allegedly incriminating Facebook posts and accuses Ghram of “inciting actions of looting.”

The public prosecutor of Ben Arous First Instance Court interrogated Ghram after the police did and ordered his detention. Ghram was held in Mornag Civil Prison, where his family visited him twice and where he had access to his lawyer. On January 28, the Ben Arous First Instance court acquitted Ghram of all charges, and he was released the same day.

Louhichie, who is an activist and medical consultant with the LTDH and has been visiting detained protesters in Mornag prison since the protests started, said that she observed marks of beatings on the bodies and faces of at least 16 detained protesters, between the ages of 18 and 37. She said the detainees told her the beatings occurred during the arrest phase.

Apparent Arbitrary Arrest

Montassar Sellem, a 20-year-old law student and member of the Tunisian Communist Youth, said that the National Security Police of Ariana, in northwestern Tunis, arrested him on January 17 at 2 p.m. while he was running an errand in the Hedi Nouira neighborhood:

At least six officers came in one police car and in another ordinary one. Four arrested me and another young man, also named Montassar. Police took me without a formal detention order to Ariana Judicial Police Headquarters. I gave them two numbers: the number of my mother and that of my lawyer. They only called my mother, who came and saw me briefly, but did not call the lawyer. No one told me why I was arrested. Police officers took my phone and made me disclose the password. They started to read my Facebook posts and commented on one of the hashtags I had used, which said “corrupt system.”

One officer interrogated me, but at least seven others were coming in and out of the room cursing me, saying I would rot in prison and asking me all sorts of random questions such as, “What are your political affiliations? Are you a freemason? Do you work with intelligence? Are you patriotic? Are you with Israel? Did anyone from your family fight in Syria or Iraq? Do you have a passport? Did you travel before?”

Sellem said he insisted that he should have a lawyer present during his interrogation, but he was refused one. He says police cursed him during the interrogation:

The officers did not give me the final report to read but I got a sneak peek because it was on the table in front of me. Police pressured me into signing the report. My lawyer arrived at 9 p.m. when everything was over. During the investigation, they did not beat me, but interrogators beat up other protesters in front of me to intimidate me.

Sellem, who spent two nights in Bouchoucha detention center, said he was not given any preventive items to reduce the risk of Covid-19 transmission, such as a mask or hand sanitizer. He described overcrowding and filthy conditions in his cell:

They detained me in a room with at least 100 detainees, including people detained for protests but also others. It was horrible. The room was extremely dirty, there was no soap for washing or other hygienic items. Some detainees spent the night standing for lack of space. Neither my family nor my lawyer saw me during the two nights. The food was bad and detainees had to share dishes.

The Public Prosecutor accused Sellem of “forming an organized group for an unspecified period of time, with an unspecified number of people with the purpose of attacking persons or property which is considered a crime against public order,” under article 131 of the Penal Code. He said he was first taken to the Ben Arous Public Prosecutor’s Office on January 18 but did not see the prosecutor until the next day. Sellem said that the court’s judge asked him what happened and then acquitted him of forming a criminal group but fined him 500 TND (around US$180) for “breaching the curfew” and “breaching the [Covid 19] sanitary protocol in place,” and released him that day.

Arrested for ‘Insulting’ a Police Officer

Hamza Nasri Jerridi, 27, an activist and vice president of the LTDH’s Tunis section, said that National Security officers arrested him for “insulting a police officer” at around 3 p.m. on January 18, during a peaceful protest on Habib Bourguiba Avenue. Jerridi said he spent three days in jail because he had raised his middle finger at police during the protest:

Police officers took me to Beb Souika police station in Tunis and interrogated me in the presence of one of my lawyers, after I insisted that one lawyer be present. Officers asked me questions like, “What’s your problem with the police officers?” and “Why did you make that indecent gesture.” I answered that I did not see it as inappropriate and that I consider it a form of protesting.

I ended up spending three nights at Bouchoucha detention center, where conditions were horrible: there was no clean water and no soap for detainees to wash our hands. I was in a crowded room with around 80 other detainees and was not offered a blanket or mattress and slept on the floor all three nights. I was also denied my spectacles, which I need. The detention center was extremely dirty. We were not given masks or other protective items, such as hand sanitizer.

Jerridi said that officers did not beat or mistreat him but that some threatened that he would “rot in prison.”

Jerridi said that he appeared before an investigative judge of the Tunis 1 First Instance Court on January 21, accused of “insulting a police officer” and “committing an immoral act in public,” both punishable with up to six months in prison, and for “offending good morals and public indecency.”

The judge provisionally released Jerridi, pending trial. As of January 29, he had not been notified of a trial date.

Harassment of Journalists

Ghaya Ben Mbarek, a journalist with the English language independent reporting platform Meshkal who covered the protests in Tunis on January 23, said that police harassed her and another journalist with her to turn over footage she had taken:

When I started to film, at least 10 police officers approached me and one of them tried to snatch away the phone. They demanded to see the footage and insisted to know whether the face of one of the officers who just arrested an activist was recognizable in the footage. I refused to give them my phone and told them I was from the press and that I had accreditation. The police cornered me and the other journalist, asked for our IDs and then proceeded to film them as well as our press accreditations.

Video Analysis

In a 38-second video posted on Facebook on the evening of January 17, 10 police officers, some in uniform and others in civilian clothing, can be seen dragging a man along on a street toward the flashing lights of a parked vehicle. The officers hit the man repeatedly with batons and kick him once while dragging him. The man appears to be immobilized and not resisting arrest. The video was filmed at night from the first or second story of a building overlooking a small street, believed to be in the town of Siliana.

The officers can be heard cursing at people who are off camera at the other end of the street and calling the man they had arrested “one of the sheep.” Some officers also shout at people observing the violent scene from their balconies. It is not clear if the man had been protesting. Human Rights Watch was unable to independently verify the location or date of the incident.

In a video posted on the Facebook page of Tunisie Politique magazine on January 19, a man can be seen coughing as he leaves a house. The person filming the video enters a gas-filled room, which is clearly visible in the footage, and is then seen quickly leaving the house coughing and struggling to breathe. The title of the video said that it was taken in Tebourba, but Human Rights Watch was unable to independently verify the location or the date of this incident.

The person filming the video can be heard saying “Look what Tebourba police hit people’s houses with: teargas, look!” The man filming continues to cough, and a woman can heard saying “Is the house still filled with teargas,” to which he responds “Leave it [the house] at least for one hour.”

Legal Standards

As a state party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights since 1969, Tunisia is obligated to guarantee the right of peaceful assembly, and that “no restrictions may be placed on the exercise of this right other than those imposed in conformity with the law and which are necessary in a democratic society in the interests of national security or public safety, public order (ordre public), the protection of public health or morals or the protection of the rights and freedoms of others.”

Tunisia is also a state party since 1983 to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, which under article 11 states that “Every individual shall have the right to assemble freely with others. The exercise of this right shall be subject only to necessary restrictions provided for by law, in particular, those enacted in the interest of national security, the safety, health, ethics and rights and freedoms of others.”

The Arab Charter of Human Rights adopted in 1994 guarantees to every citizen the right of freedom of peaceful assembly.

Article 37 of the Tunisian Constitution from 2014 guarantees the right to “assembly and peaceful demonstration.”

International law obligations override Tunisian Law No. 69/4 on regulating assemblies that allows police to disperse an assembly and a counterterrorism law from 2015 that permits security forces to disperse assemblies on sweeping grounds.

International standards stipulate that security forces should use the minimum necessary force at all times during protests. International norms on the use of teargas projectiles say they should only be used to disperse unlawful assemblies where necessary and proportionate and that they should be fired at a high angle to avoid serious injury. Projectiles should not be fired directly at individuals or at the head or face.

Human Rights Watch opposes the use of teargas to disperse nonviolent assemblies. Long-lasting or heavy exposure to teargas can have long-term consequences for vision and respiratory health.

International human rights law, notably the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), recognizes that in the context of a serious public health threat – such as Covid-19 – restrictions on some rights can be justified. But such restrictions must have a legal basis, be strictly necessary, neither arbitrary nor discriminatory in application, of limited duration, respectful of human dignity, subject to review, and proportionate to achieve the objective.

Broad quarantines and lockdowns of indeterminate length rarely meet these criteria and are often imposed precipitously, without ensuring the protection of those under quarantine – especially at-risk populations. Because such quarantines and lockdowns are difficult to impose and enforce uniformly, they are often arbitrary or discriminatory in application.