“Tomorrow the sun will shine.”

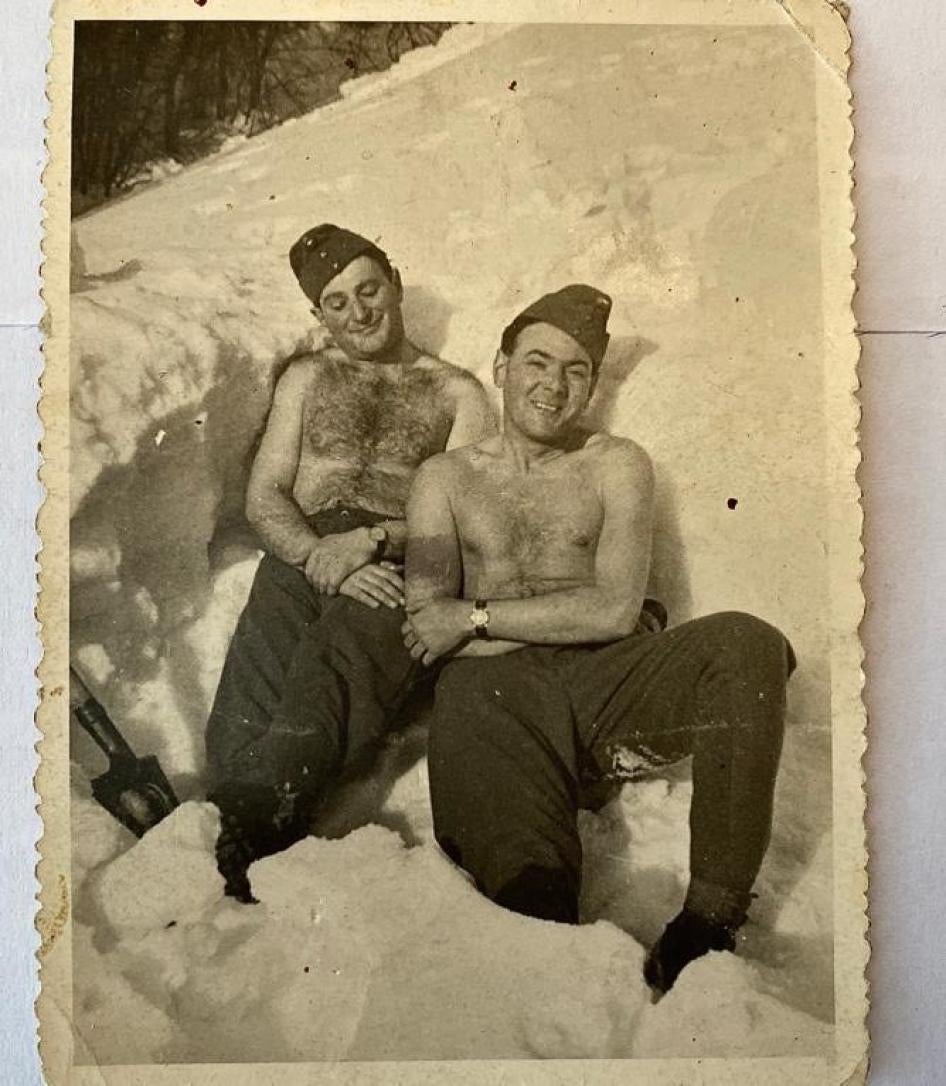

That is how my father encouraged his comrades at the overcrowded “hospital” in the Ukraine in the winter of 1943, on the eastern front of World War II. Hundreds of Hungarian Jewish forced laborers were being treated for wounds and diseases in an abandoned stall with breaking walls. Patients, tangled over beds, chairs and the floor, often found themselves in snow when they woke up in the morning. There were few doctors and almost no medicine. My father Ervin Brody had his toe amputated there, without anesthesia, to save his leg from the frostbite that had crippled him on a retreat march of more than 600 kilometers though the Russian winter after their German masters had been defeated at Stalingrad. Of the 265 men in his labor company, only a few dozen survived. His steel discipline and his physical strength, as a championship tennis player, pulled him through that ordeal, as they would his entire life.

The siege of Budapest

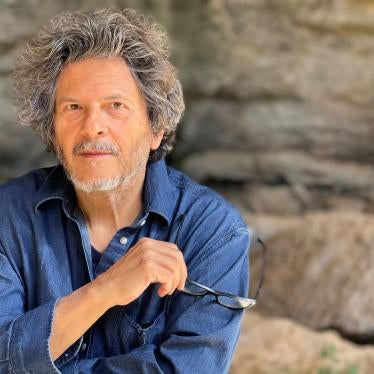

“Tomorrow the sun will shine” is a kind of a mantra in my family. In the 23 years since my father died, I have thought a lot “Mompi,” as we called him ever since I couldn’t pronounce “mon papa” as a baby. My life as a human rights activist, which has taken me to war-zones, refugee camps and ghettos across the globe, has been a constant reminder that despite my privileged position, I live only one generation removed from the conflict and turmoil of Mompi’s world. Or perhaps only one pandemic away. In Barcelona, where I have been in lock-down, thousands have died in the overburdened make-shift hospitals. At least here there are doctors, medicine and no snow. In New York, where we grew up, Mompi’s widow (my step-mother) died last month of natural causes at 96, but the virus prevented us from being with her.

After he returned from the Ukraine, the Hungarian collaborationist government sent Mompi to a large labor battalion at a Yugoslav copper mine where a sadistic commander took pleasure in torturing the workers. The battalion was disbanded in the face of a Soviet advance in October 1944, and thousands of Jews were shot by the retreating Germans on a forced march towards Hungary. When news of the massacre made it back to my father’s family in Budapest, they assumed he was dead, but he had managed to escape during a thunderstorm with some friends. Mompi often told me that one of the happiest sights of his life, after three days wending through a forest to avoid detection, was the red star on the cap of one of Marshal Tito’s communist Partisans manning a machine-gun position. From there, my father joined the advancing Soviet army as a translator and auxiliary and marched with them to the siege of Budapest, his home.

By that time, early 1945, Germany had directly occupied Hungary and Adolf Eichmann was shipping Jews off to Auschwitz. My father was worried that his family had met such a fate and, throwing caution to the wind, decided to enter the besieged city to find out. Crawling through the snow in his Soviet uniform, carrying a rifle and a jar of butter as a gift, he was shot in the hand – his third bullet in the war – before finally reaching his mother’s apartment building near the Danube, a building I visited many times over 30 years later. He rang the doorbell of their apartment and soon his mother opened the door to see a Russian soldier in front of her. Fearing the soldier had come to loot the apartment, she protested in broken Russian that she was an old, poor woman. “But Mother, don’t you recognize me?” my father asked. Then his mother began to sob hysterically. Her son, who she thought was dead, was still alive.

The New York years

My father worked for the Soviets after they liberated Budapest, but he wanted to escape that world and followed an Austrian woman to Vienna. In that divided city, he worked for the American army as a train yardmaster and interpreter helping move POWs and refugees. He adored the can-do, American soldiers and their easy slang, and they valued this athletic multi-lingual European who could deal with the Russians, the Hungarians and the Austrians. In 1947, they helped him get passage to his dream country – the United States – with 755 other displaced people.

Arriving penniless at age 38, his ordeals were not over. His relatives in New York had no time for him. After three lonely years, he fell in love and married but his wife, pregnant with his first child, committed suicide. He was fired from a good export job to make room for the boss’ mistress. Eventually, he went back to college and graduate school while still working full-time, earning his doctorate from Columbia University when he was 59. After falsifying his records, to take 10 years off his age, he finally spent his last 28 years placidly teaching at a bucolic university to adoring students, surrounded by a loving wife and two (mostly) worshipful kids.

Learning from my father

My father taught his literature and language classes from the treasure house of personal experience, from what he ironically called his “European Education” (“my diplomas?” he once wrote, “I wear them on my body”). He created a Russian area studies program at his university, well before US-Soviet détente, as a way of promoting dialogue between two peoples he loved. My up-bringing was full of historical and literary references. When I set up the black pieces for our chess matches, we pretended I was the Russian General Kutuzov, from Tolstoy’s War and Peace, drawing Napoleon’s troops to enter my territory only to be defeated by the Russian winter, as Hitler’s troops would be a century later. In college, I took my father’s classes on Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, Solzhenitsyn and his hero (and mine) Albert Camus. It was there, when a fawning student imitated him to me, that I first realized Mompi spoke with a thick Hungarian accent. (“Wait,” I said, “my father sounds like Zsa Zsa Gabor?”)

Rebukes from a president

An idealistic young lawyer, my life changed when I took a 1984 trip to Nicaragua to witness the Sandinista revolution. In a mountain village where I knew the priest, townsfolk beseeched me to alert Americans to the killings being carried out by “contra” fighters, backed by the United States. I quit my job as Assistant Attorney General in New York State to investigate for myself. My father, whose life was a journey from the hunger and uncertainty of central Europe to the stability of a tenured professorship in America, was aghast that I would not only give up a steady job but deliberately put myself in harm’s way. Having lived through the heralding of so many new ideological dawns, he also worried that I was starry-eyed about the Sandinistas. When he saw a letter (containing $1000 I had raised for the village health clinic) which I signed with the Sandinista rallying cry “free homeland or death,” he ridiculed my empty sloganeering.

I went anyway. For five months, I crisscrossed Nicaragua’s remote war zones with priests going to say mass and came back with hundreds of accounts of killings, torture and rape. '' Reedy, '' my father said, '' when you went to Nicaragua, I was afraid you were going to come back a Communist, but a Catholic I never expected.'' My ensuing report made the front page of the New York Times and helped force a Congressional cut-off in U.S. aid to the contras. The best part for Mompi, I think, was that I earned a rebuke from President Ronald Reagan, whom he hated then more than anybody. (In those days it was still rare to be called out by a US president.)

My father’s pride soared as I embarked on a life trying to combat injustice. He once compared me with Camus’ Dr Bernard Rieux fighting fascism in the guise of The Plague . I often felt more like Camus’ Sisyphus, however, eternally pushing the rock up the hill only to have it roll back down – but happy with "the struggle itself towards the heights." In places like Haiti, Tibet, East Timor, Standing Rock North Dakota and the Congo, I have lost many more battles than I have won. But that has only made the victories more sweet. In 1998, the year after Mompi’s death at 87, I was at the British House of Lords working on the case against the former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet, one of Mompi’s most despised figures. The day the Lords ruled that Pinochet did not have immunity from torture charges, I wore Mompi’s old overcoat to court.

Finding the documents

I often thought (and still think) that my father embellished or exaggerated his stories, but two years ago, when I was cleaning out my step-mother’s apartment, I came across boxes of materials in a closet that corroborated his hardships and his strength. They included family letters from the war years, his work brigade orders, a safe-conduct from Tito’s army, recommendations from the US army in Vienna. Even an unpublished book by a friend who was on the long retreat from his labor camp in the Soviet Union who - wrote– mistakenly - “One morning we found Ervin on the road frozen to death.”

Years earlier, I broke open the atrocity case against a former Chadian dictator by stumbling on the abandoned files of his secret police, but my joy at that find was nothing compared to the exhilaration of unlocking secrets of Mompi’s life. I found letters between my father’s own parents, dating back to 1895, describing their plight in the village of Sátoraljaújhely, Hungary where my grandfather Kálmán, a poor-people’s lawyer, died nearly destitute when Mompi was 13. There were pictures of his Viennese wife, who did not follow him as expected to America. There were bundles and bundles of aerograms – weekly correspondence over decades between my father in America, and his mother, sister and brother back home. I even learned they had a fourth sibling who died when my father was two.

A cardboard box marked “Blanche,” tied tightly with string, uncloaked the story of his wife’s suicide. Pictures showed a beautiful woman and a happy couple on the beach and the tennis court who met at Thanksgiving and were married by January. Notes and letters revealed two years later, however, a woman paralyzed by pregnancy and tormented by whether to have the baby: references to an abortion she could not go through with; loving notes from my father; Blanche’s scrawled notes to herself (“I feel as if I am in a burning house with all the doors closed”). Then the Medical Examiner’s report - a 39-year old woman dead of barbiturate poisoning in their small Manhattan studio apartment, seven months pregnant with a girl, and Blanche’s suicide note to my father saying that she saw no way out. After her death, my father poured his heart out in a 5-page letter to his sister in Hungary. Blanche had been an abused child and could not face the burden of giving birth, he said. “I told her about the harsh circumstances I lived in the labor camp, how I went away with a frozen leg, typhoid fever and begged her to trust in her own strength.”

But my father, too, was faltering. In language I never imagined him using, he even told his sister that his death would be a deliverance. “I do not know how in the world am I going to embark all over again walking down this path.” But, once more, he did find his strength. I was born only 17 months after Blanche’s suicide, the result of Mompi’s short-lived relationship with my mother, an activist artist and schoolteacher. Then my father met “Prettynka,” the ”best thing that ever happened to me.” She would give him another child, my brother Clifford, and, finally, 43 years of stability and happiness.

In moments of crisis, I lean on my father's resilience and his conviction that better days would come. Camus taught us that "the only way to fight the plague is with decency". Whether it is saving the sick and preventing infections, like Dr Rieux, standing up for the most vulnerable, or simply, helping our family and others survive, we are all called on now to find our inner strength, the strength of our forebearers.

For tomorrow the sun will shine.