Many workers at meat and poultry plants across the United States are battling for their health during the Covid-19 pandemic. As Human Rights Watch has reported, it’s a crisis that’s been brewing before the outbreak began.

Recent developments have been alarming. A Smithfield pork plant closed indefinitely after it became the epicenter of the Covid-19 outbreak in South Dakota, with nearly 1,000 confirmed cases, the biggest cluster in the country. JBS has temporarily shuttered a pork plant in Minnesota and a beef plant in Colorado because of the coronavirus crisis. The media reported that two Tyson Foods workers died in Iowa and four in Georgia from Covid-19. Tyson plants in Tennessee and Kansas have dozens of cases each, and a facility in Waterloo, Iowa suspended operations after local authorities implored Tyson to close due to an outbreak there.

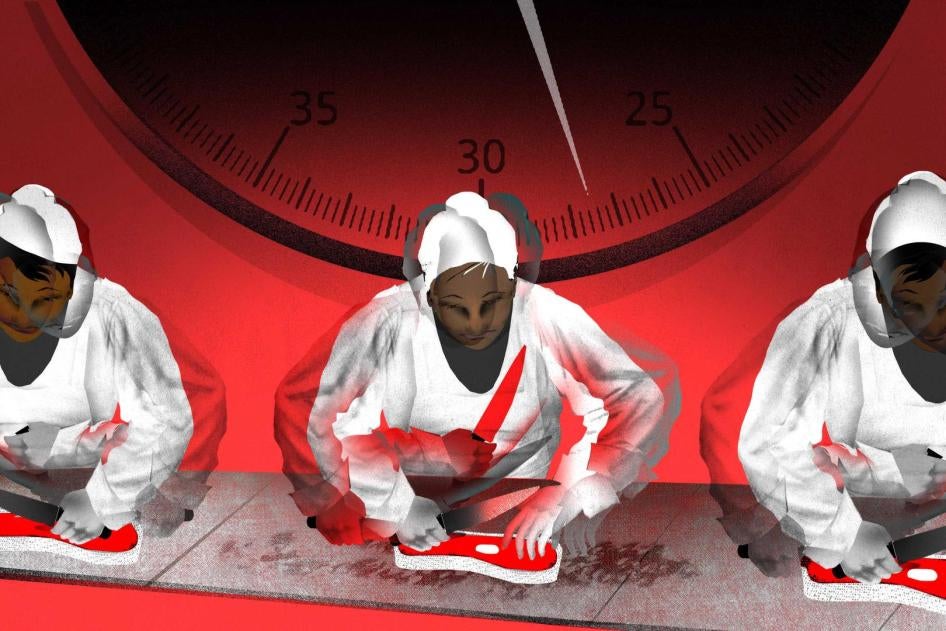

Though disturbing, the spread of coronavirus in US meat and poultry plants shouldn’t surprise anyone familiar with the facilities’ conditions: workers kill, cut, debone, and package meat in cramped quarters, working elbow to elbow, coated with grease and blood. They work amidst deafening noise and the smell of dead animals and overpowering chemicals. We documented the dangers of meatpacking work in our 2019 report, “‘When We’re Dead and Buried, Our Bones Will Keep Hurting’: Workers’ Rights Under Threat in US Meat and Poultry Plants,” and our findings were chilling.

Workers we spoke to for the report described their exhaustion and chronic pain resulting from making the same, forceful motions tens of thousands of times each day, which often caused severe and debilitating injuries. The harsh conditions and close proximity of workers are petri dishes for a highly communicable disease. It’s no wonder that the spread of the novel coronavirus in meatpacking facilities may be worse than originally thought.

Even before the pandemic hit, Human Rights Watch found the response of companies to medical issues and injuries in their facilities to be disturbingly inadequate. Workers told us they were pressured not to report injuries and feared retaliation if they left the slaughter line to seek medical treatment. In-house medical units encouraged workers to return to the line after cursory care, even when workers felt they needed more substantive help.

Government investigations have also found that these medical units in some facilities failed to make timely and appropriate medical referrals. In one case, a worker suffered a serious injury when her hand was trapped and burned by a machine. The incident occurred on a Friday and she was told to return to work, with her other hand, on Monday morning at 6:30 a.m. if she wanted to get paid.

Compounding the problem is the power imbalances that keep workers from reporting workplace safety hazards. Plant workers depend on these jobs for themselves and their families, and fear losing them. Many of the low-wage workers in meatpacking and processing plants are from marginalized communities, with many people of color and women making up their ranks. Nearly one-third are immigrants, including a significant number who are undocumented. Many of the workers we interviewed requested anonymity because they feared repercussions for their immigration status as well as their employment. A lot of the immigrant workers who do not have social security numbers will not receive coronavirus stimulus checks, even if they have been paying taxes. The decline in the prevalence of unions and collective bargaining agreements in meatpacking facilities also hurts workers’ ability to address these issues.

The challenging conditions for meatpacking workers have been magnified by Covid-19. Workers have described to nongovernmental organizations the crowded working conditions, pressure to continue working through illness, and denial of personal protective equipment. They have reported that companies have been slow to implement measures to ensure social distancing in their facilities. Human Rights Watch joined a number of civil society and workers organizations to call for improved health and safety conditions in plants during the pandemic, paid sick and family leave for workers caring for themselves or others, premium pay for hazardous work, and protection against retaliation.

Meat processing jobs are some of the country’s most dangerous. Instead of attempting to improve safety for these and other essential frontline workers, the Trump administration has made it easier for meat and poultry plants to operate faster, increasing the danger of injury and other harm. Prior to the pandemic, the administration aggressively promoted deregulation of slaughter inspection systems that impose line speeds in facilities. In September 2019, a new rule removed caps on line speeds in pork facilities, opening the door for them to operate as quickly as possible, despite increased line speeds correlating with more worker injuries.

The administration has also issued waivers for line speed restrictions in other meat processing facilities. In April 2020 alone, the administration issued 15 waivers to poultry facilities, including 6 to Tyson Foods. In March, they issued the first waiver to a beef processing facility, also owned by Tyson.

These rollbacks of safety rules not only raise the already high risks to meatpacking workers, but also jeopardize the security and stability of our food systems. The impacts of the pandemic on these dangerous workplaces has already shut down approximately 25 percent of the nation’s pork processing, and slowdowns in other sectors may follow.

But these changes to safety rules do not have to be permanent, and reinstating protections should be a priority of candidates seeking voters’ trust in the 2020 elections. Protecting all workers – especially those at the front lines who are risking their lives to feed the country– should be a priority for all branches of government.

Regulations safeguarding the health and safety of our workers can and should be reinstated and strengthened. As voters prepare to go to the polls in November, they should be asking which candidates are the most serious about protecting our frontline essential workers through evidence-based policies.