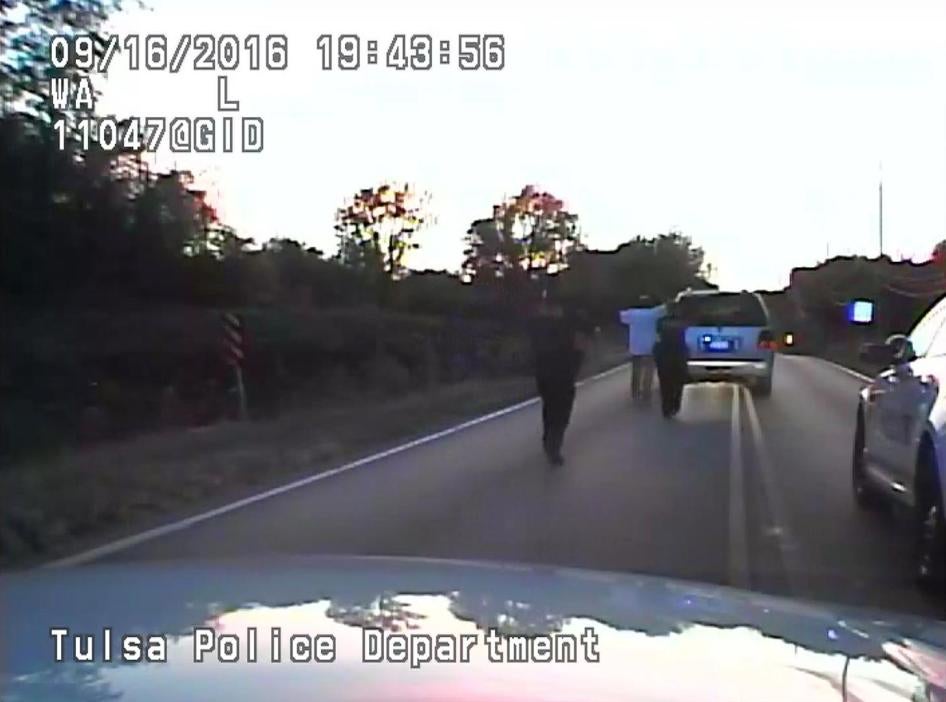

The deaths of Joshua Barre, shot and killed by Tulsa police officers and sheriff’s deputies, and Joshua Harvey, who lost consciousness and later died after being tasered multiple times by Tulsa officers, point to the dangers of having police respond to people showing signs of having mental health conditions.

Millions of Americans have a mental health condition, including things like depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress syndrome, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia. The vast majority of people with mental health conditions are not violent and do not violate laws, but rather are more likely to be victims of violence themselves. People with actual or perceived mental health conditions are among the most stigmatized and marginalized in the US.

Community-based social services are important to help support people to cope with the difficulties of daily life and manage their conditions. Oklahoma, including Tulsa, has high rates of people with mental health conditions, many of whom are not receiving adequate support services. Funding cuts at the state level for the mental health system and lack of adequately funded services at the local level have decreased support for people with mental health conditions. Occasionally, people reach a crisis, particularly if they lack support.

Police as the primary response to people with mental health conditions

More and more, police, throughout the US and in Tulsa, are being called upon as the primary responders to people with mental health conditions, especially when they are in crisis. While occasionally, people with mental health conditions behave in ways that call for police intervention, more often, a better response is from specifically trained mental health workers with therapeutic skills and tools.

Nationally, about 20 percent of calls police respond to involve people with mental health conditions. Tulsa police received about 13,000 such calls in 2017. Tulsa Police Department’s leadership recognizes that addressing situations involving people with mental health conditions is one of its most pressing concerns and takes up much of its resources. Many within law enforcement also realize that police are not the best response for people in crisis and that mental health should generally not be treated as a law enforcement issue.

Police responding to people with mental health conditions can sometimes enhance the danger. In 2018, of 998 people shot and killed by police across the country, 21 percent had a known mental health condition; in 2017, it was 24 percent. It is unclear how many of these deaths could have been avoided through the involvement of mental health professionals equipped with different training and skills providing a more supportive and calming response. Some Tulsans told Human Rights Watch that they feared calling the police when their loved ones with mental health conditions acted dangerously.

Alternatives to Police

To their credit, Tulsa Police provide more training than most law enforcement agencies on addressing situations involving people with mental health conditions. However, more training is not the answer. Even with additional training, police are poorly equipped to respond to people with mental health conditions in crisis. Police are still oriented towards “command and control” and their tools too often involve force and arrest. The mental health training Tulsa police officers generally get pales in comparison to the skills and training mental health professionals receive. These professionals should be the primary responders in most situations involving those with mental health conditions.

Tulsa has an agency called Community Outreach Psychiatric Emergency Services (“COPES”) which employs mental health professionals and responds to people in crisis. More calls could be diverted to COPES. The Tulsa Police Department is developing a way to properly direct 911 calls to COPES, the more appropriate agency, which could potentially serve as a model for other cities.

Tulsa Police also have created a pilot project that assigns officers with paramedics and COPES counselors, who together respond to incidents potentially involving a person with a mental health condition. This project has had success, but police only deploy it two shifts per week and the project requires more funding to meet needs.

The Tulsa Fire Department, together with area health providers, has created a program to identify people with high mental health and other support needs to connect them with ongoing services and cut the need for emergency response. Again, this program lacks funding to meet needs.

The state mental health system could be enhanced to meet the needs of the community on a non-emergency basis, which should limit the instances of emergency response.

Wherever appropriate, and as much as possible, mental health workers should be the preferred option for responding to people with mental health conditions.