Abusive policing in Tulsa, Oklahoma that targets black people and poor people, diminishes the quality of life in all communities, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today. Human Rights Watch released the report on the eve of the third anniversary of the killing of Terence Crutcher, an unarmed black man. That killing led Human Rights Watch to investigate everyday police interactions in Tulsa as a window into the larger human rights problems with policing throughout the United States.

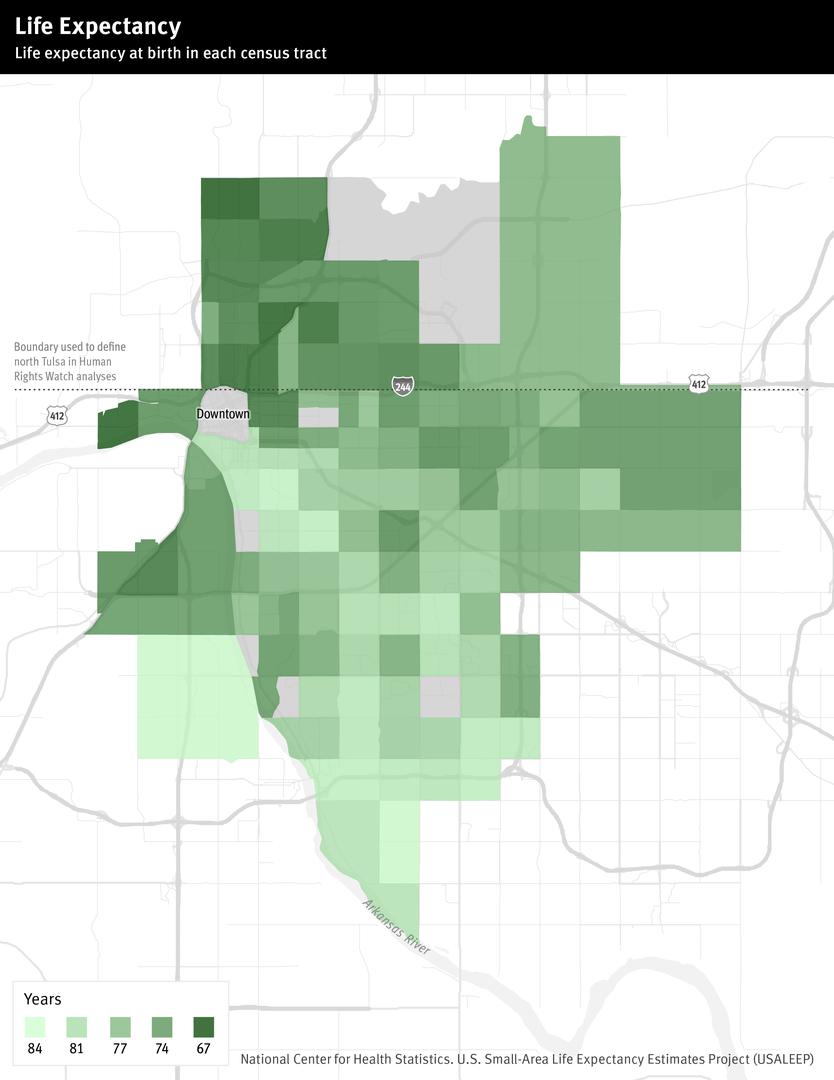

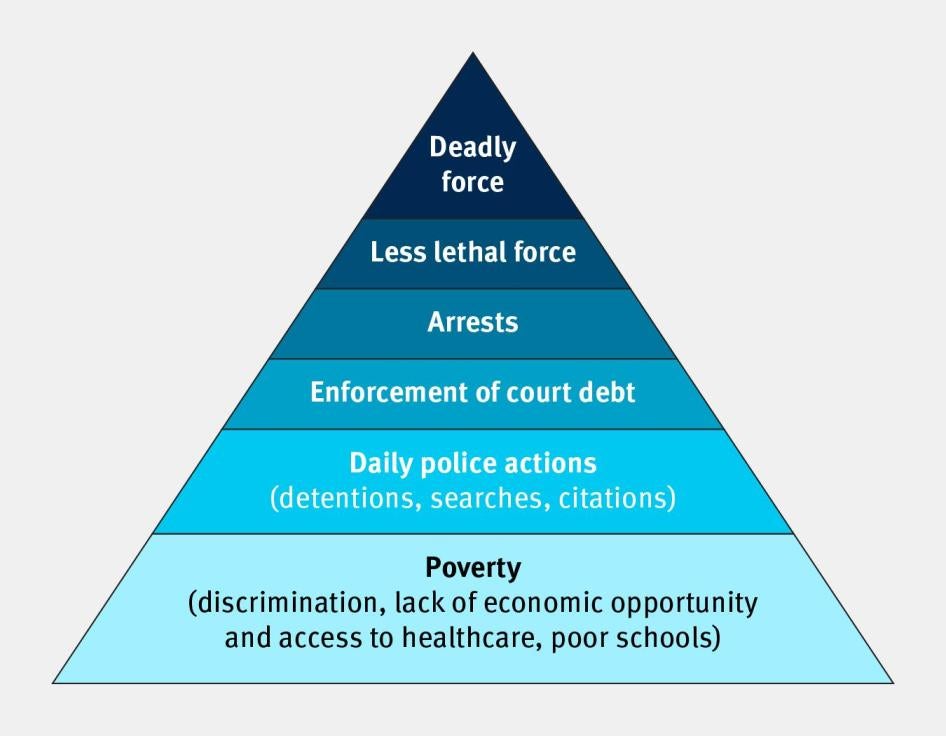

The 216-page report, “‘Get on the Ground!’: Policing, Poverty, and Racial Inequality in Tulsa, Oklahoma,” details how policing affects Tulsa, particularly in the segregated and largely impoverished North Tulsa area. Human Rights Watch found that black people are subjected to physical force, including tasers, police dog bites, pepper spray, punches, and kicks, at a rate 2.7 times that of white people. Some neighborhoods with larger populations of black people and poor people experienced police stops more than 10 times the rate of predominantly white and wealthier neighborhoods. Arrests and citations lead to staggering accumulations of court fees, fines, and costs, often for very minor offenses, that trap poor people in a cycle of debt and further arrests for failing to pay.

“Black people and poor people in Tulsa experience abusive and intimidating policing,” said John Raphling, senior US researcher at Human Rights Watch and author of the report. “The killing of Terence Crutcher, like so many high-profile police killings of black men throughout the country, has helped expose the often discriminatory and brutal everyday tactics used by law enforcement, and the need for fundamental reforms.”

From 2015 through 2018, police in the US shot and killed 3,943 people, according to the Washington Post tracker of police killings. Nearly a quarter of those killed were black, though black people make up only 13.4 percent of the overall population.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 132 people, including 57 who had directly, or through a family member, experienced abusive policing in Tulsa, as well as elected officials, police officers and commanders, community organizers, church leaders, social service providers, researchers, academics, and other community advocates. Human Rights Watch also reviewed data provided by the city, its police department, and the courts about arrests, deadly and nondeadly uses of force, complaints, detentions, citations and court fees, fines, and costs.

Black Tulsans described violent encounters with police. In one case, police handcuffed Ira Wilkins outside his car after he fell asleep in the driver’s seat in a parking lot. The officers bent his wrists behind his back, accused him of resisting, then threw him to the ground and pepper-sprayed him in the eyes.

Black Tulsans described abusive and aggressive traffic stops and tickets for relatively minor alleged violations:

- Sandra Rousseau said that her son was frequently stopped, searched, checked for warrants, and even photographed by Tulsa police officers when he went out with friends.

- A Tulsa police officer described responding to a call in which a group of other officers had detained a black man walking on the sidewalk without justification, “to find out who he was.” The officer said this type of stop happens frequently.

- Isabella Shadrack said she was stopped and ordered out of her car at gunpoint, while her 7-year-old daughter watched in terror from the back seat. Officers said they were investigating a stolen car, though no one had reported this car stolen.

- Julian Givens described being detained for not stopping at a stop sign, and being ordered to sit on the curb, handcuffed, while police searched his car without permission.

According to the department’s own data, of 3,364 distinct acts of “non-lethal” force by Tulsa police from 2012 through 2017, the police department found only two were “out of policy,” and imposed no discipline for either.

Tulsa was the scene of devastating racial violence in 1921 when a mob of white people invaded the affluent black community of Greenwood, looting and burning businesses, and killing hundreds. To this day, black Tulsans, especially in North Tulsa, which includes Greenwood, experience significant poverty, high unemployment, meager economic development, and segregated schools. This poverty substantially impacts crime and policing; overaggressive policing contributes to the poverty.

The high rate of court debt owed by poor people in Tulsa is both a result of and a compounding factor in the community’s high rates of poverty. The courts impose an array of fines, fees, and court costs on those arrested and cited by police, many of which are used to fund the court system itself. Poor people cannot pay, leading the courts to issue warrants for “failure to pay.” Police then detain, search, and arrest people who are subject to these warrants. Arrest on the warrants leads to further accumulation of debt. Arrests by Tulsa Police for failure to pay court costs is one of the leading reasons for booking in the county jail.

Community leaders in Tulsa have pressed for changes and city officials have recognized that these disparities exist and acknowledged complaints of abusive policing practices. Mayor GT Bynum has begun a process of reform. However, the reforms so far fail to create adequate oversight and accountability mechanisms, and they rarely mandate significant changes in policing practices.

The city has crucial decisions to make about the strength of its reform efforts, Human Rights Watch said. Changes in the conduct of policing are necessary, as is an independent oversight body with meaningful authority. More fundamentally, the city, state, and federal governments should promote economic development in impoverished areas. They should also improve the availability of services, like affordable housing and mental health care and support, that will address some of the root causes of crime, instead of making police the default response to so many societal problems.

“True reform requires fundamental changes in the role police play in the community and how communities achieve public safety,” Raphling said. “Abusive policing tactics, especially when they have a discriminatory effect, will not make anyone safer.”

Click here for a special interactive data feature on policing, poverty and racial inequality in Tulsa, Oklahoma.