(New York) – A Minnesota case that ended with a verdict for the plaintiff on June 19, 2019 is one of several federal lawsuits against police departments for unlawfully accessing a colleague’s private information in driver’s license databases, Human Rights Watch said today. The cases are part of a nationwide phenomenon of such claims that highlight the need for stronger data protections in the United States.

In a Saint Paul courtroom in June, attorneys for officer Amy Krekelberg said that 58 officers from the Minneapolis Police Department, most of them men, had broken a federal privacy law and inflicted emotional distress on Krekelberg by searching for her data 74 times without a lawful purpose. The information included her photograph, address, age, height, and weight. The jury awarded Krekelberg $585,000.

“The Minnesota case shows that without strong protections, police officers may abuse their data access – even by invading the privacy of their fellow officers, particularly women,” said Sarah St.Vincent, US surveillance and law enforcement researcher at Human Rights Watch, who observed the trial. “As Congress and the states consider adopting stronger data protections, they should limit what police can do with personal information.”

Krekelberg’s attorneys portrayed the searches for her data as a failure by officers to respect a female colleague and part of a broader climate of hostility and harassment toward female officers. The federal Civil Rights Act prohibits sex discrimination, including sexual harassment, although Krekelberg’s case did not allege violations of that law.

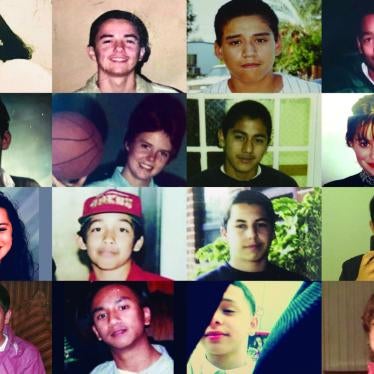

Krekelberg’s case is one of at least 14 federal lawsuits since 2009 that Human Rights Watch has identified in which evidence was introduced to support claims that law enforcement officers misused their access to large collections of personal data to peer into the lives of fellow police, public safety personnel, and justice professionals.

Several of the suits were brought by women who contended that officers had searched for their data due to curiosity about physical appearance or relationships, or otherwise in a broader context of alleged sexual harassment. One suit in northern Alabama was brought by a woman who alleged that police needlessly pried into data about her past convictions to pressure her romantic partner, an officer, into resigning from the force. The other cases were brought by people who were in policing, safety, or justice roles themselves.

Allegations in civil suits do not necessarily prove that abuse occurred, and many suits never reach a final judgment. However, the cases examined raise troubling questions about the potential harm to human rights of insufficiently checked police access to personal data, Human Rights Watch said.

Of the federal lawsuits Human Rights Watch reviewed, eight were brought in Minnesota, where state law provides a right to request an audit of searches for one’s driver’s license data in the state’s Driver and Vehicle Services database. Reporting about other alleged instances of officers misusing their database access suggests the “fellow officer” lookups that have reached federal court may only represent the tip of the iceberg.

In addition to driver’s license databases, police nationwide often have access to other databases containing large amounts of personal data.

Under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, to which the US is a party, police should not search personal data in a way that interferes with the right to privacy unless the queries are lawful, subject to adequate safeguards, and strictly necessary for achieving a legitimate goal such as investigating serious crimes.

The federal Driver’s Privacy Protection Act makes it illegal for anyone to obtain personal information connected with driving records except in limited circumstances, such as those related to driver safety or car theft.

Overall, however, the federal privacy protection framework is often weak or incomplete, Human Rights Watch said. While some protections exist for certain financial, educational, and health data, many other types of personal information are left largely unregulated.

In 2007, a former Saint Paul police officer, Anne Rasmusson, grew suspicious of officers who – she said – expressed romantic interest in her and had somehow learned where she lived. When she requested an audit of searches for her driver’s license data, she discovered that officers had looked up her photo and other data over 500 times. In 2012, she sued for alleged privacy violations, leading to settlements totaling more than $1 million.

In the wake of Rasmusson’s case, a range of Minnesotans, from other police officers to local members of the media and politicians, sought audits of searches for their driver’s license data and found police had accessed their information numerous times.

In 2013, Krekelberg requested an audit of police access to her driver’s license data. Her suit claimed that very few of the recorded viewings of her data by Minneapolis police officers between 2009 and 2012 could have been carried out for a legitimate purpose.

In opening and closing statements, an attorney for the city of Minneapolis, which oversees the police department, disputed Krekelberg’s claims that many of the searches could not have had a legitimate purpose and that Krekelberg would have suffered emotional harm upon learning of the data searches.

In addition to Krekelberg and Rasmusson, at least six other women who have served as Minnesota police officers, a firefighter, a public defender, and a judge have brought federal lawsuits alleging improper access to their driver’s license data by police in the state.

A state official testified during Krekelberg’s trial that “law enforcement officers and celebrities” were among the people whose data police most frequently looked up and that the majority of police officers targeted in these searches were women.

Though the violations in the Minnesota cases were serious, several data protections there help strengthen respect for rights. For example, the Minnesota driver’s license database automatically keeps a log of users’ searches, enabling officials to provide audits upon request. The Minneapolis Police Department also increased the penalty for officer misuse of the data in January 2012 after state authorities expressed concerns.

Krekelberg, who was named “Officer of the Year” by her previous employer, remains a member of the Minneapolis Police Department.

In response to a Human Rights Watch request for comment, the city of Minneapolis stated that “the City is exploring its options following the verdict” and added that the city’s police department “takes sexual harassment very seriously.” The department offers several ways for employees to report sexual harassment, including anonymously, and its “leadership, including its female command staff, does not and would not condone or tolerate sexual or any other form of harassment,” another city spokesperson added.

“Most people whose personal information is in databases available to police don’t have a means of finding out whether or why their data was searched – and that’s a rights problem,” St.Vincent said. “Having large pools of personal data easily available to police without strict legal controls creates obvious risks and an equally obvious need for protections and accountability.”