Why has Human Rights Watch dedicated 10 years to this subject?

We really believe that all kids everywhere are entitled to go to school and that they should feel safe in their schools wherever in the world they might be. We also feel that in countries experiencing armed conflict, making sure the next generations have the skills and experiences necessary to help rebuild their countries and societies is just indispensable if we want these societies to be peaceful in the future.

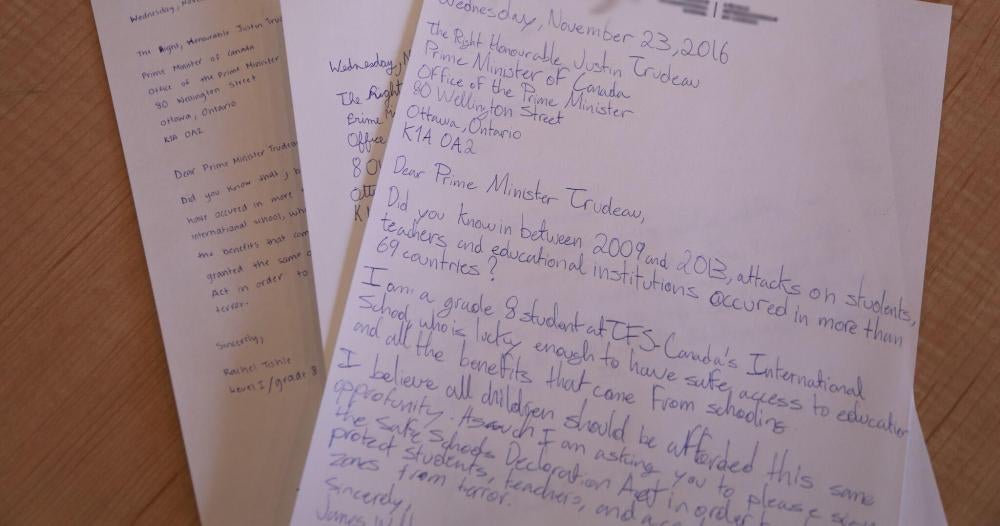

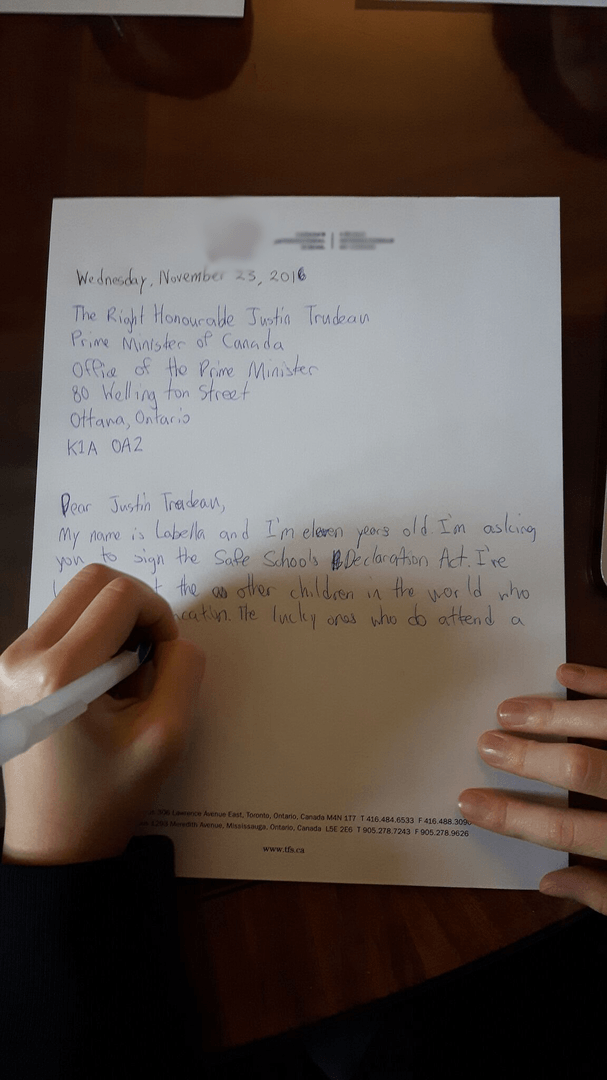

What is the Safe Schools Declaration?

The Safe Schools Declaration is a political agreement that was put together back in 2015. It lays out steps that countries can take to make it safer for students and teachers to go to school or university, even during times of war.

It says that armed forces should refrain from using schools or universities for military purposes. That means not deploying troops in schools or using schools as barracks. When soldiers are there, it can make the schools valid military targets. Sometimes troops stay in schools while the students remain, putting them at grave risk.

The declaration also calls on countries to monitor the frequency of attacks on students, teachers, and schools, and to hold people who commit laws-of-war violations against schools to account.

How is using schools for military purposes different from attacking them?

We’ve seen many cases where soldiers will take over a part of the school to live in, maybe one floor or a couple of classrooms, and the kids will be trying to carry on their studies next door. This puts kids literally in the line of fire, as the military’s presence could invite an attack by an armed group.

Schools are also used to store weapons and supplies, or to detain people.

How widespread are these issues?

In the past five years, we’ve seen incidents of militaries using schools in 30 countries. We’ve seen this in Asia, Europe, Africa, the Middle East, and the Americas. This is a global problem, and more often than not when there is war, schools are being used for military purposes.

Why are schools so appealing to militaries?

There’s a lot of reasons a school might look useful to a soldier in the field. Schools often have a perimeter wall, they are often made of cinderblocks or bricks in areas where most buildings are made of wood. They might have a couple of floors and that might make them the tallest building in a village or town, good for lookouts.

What are the consequences when schools come under attack?

In the worst cases, students and teachers have been killed and injured. The buildings themselves have been destroyed, meaning kids don’t have a permanent place to learn even after the fighting stops.

It also means the schools are likely to get lower enrollment rates. Parents of teenage girls are particularly unlikely to send their daughters to a school where there are armed men. It has a real negative consequence on kids’ ability to get an education.

Are there long-term effects on students because of a military presence in their schools?

Students are more likely to drop out of education permanently, and then they might start working while still children. Girls might get married younger or start a family when they are still children themselves. All this has a real impact on their lives and futures.

What dangers are kids facing while they study?

I particularly remember students from schools who I met in Yemen back in 2012. They were going to school while an armed group was based on the school roof. When opposition forces fired at the men in the school, the kids would be in the middle of class and have to run down to the basement to protect themselves. I remember the fear these kids felt having to take shelter in their own schools.

When I was visiting a school in Ukraine, there were these strips of red tape in a horizontal line along the corridor walls. I remember asking the person showing us around what these lines were for, and she said these were the lines the kids had to keep their heads under when moving from class to class in case the school came under attack and the windows got blown out.

Those were chilling things to realize children were dealing with.

When did Human Rights Watch first start working on this issue?

It was after the US-led invasion of Afghanistan following the September 11, 2001 attacks. My colleague Zama went to Afghanistan and started hearing stories about letters left at night at homes of teachers or along roadsides. These “night letters” demanded that schools close down or that teachers stop teaching. All just efforts by armed groups to terrorize the local communities to stop sending their kids to school. She heard stories of students being threatened on the way to school, and she started seeing a pattern of attacks on schools, particularly schools for girls.

I started working on the issue in 2009.

Has the United Nations addressed the safe schools issue?

Back in 2009, attacks on schools weren’t being talked about in international circles as a consequence of armed conflict. Now we regularly see the UN Security Council, the UN’s highest decision-making body, talking about the practice and calling for countries to take active measures to prevent it from happening.

Does the Safe Schools Declaration actually work?

One of the most remarkable things about this process is that we’ve seen governments changing their behavior after joining on. We’ve seen countries revising military manuals to put in protections to prevent schools being used for military purposes.

Also, some countries that are experiencing conflict and have endorsed the declaration have seen a decrease in the military’s use of schools.

There’s a conference in Spain in May that’s an opportunity for countries that have signed onto the declaration to share examples of what they’ve done. It’s also a chance for countries who haven’t yet joined to learn about the declaration and its benefits.

Can you think of changes made by specific countries that really stand out?

The Democratic Republic of Congo has sent out military orders saying their armed forces can’t use schools for any purposes. South Sudan has military orders saying their forces can’t use schools. Sudan has ordered security forces out of schools they were using.

In 2010, we documented that the Thai army was occupying something like 79 schools in southern Thailand, where there’s a long-time separatist insurgency. This was something people outside of that region didn’t know. Once we got the information out there, saying it was a huge risk to kids and their safety, this become problematic for the Thai government. Eventually they pulled their troops out of the schools. We estimate that something like 20,000 kids benefitted from safer schools.

Is there a school that particularly stuck with you?

Yes, a middle school in a village called Kasma in India. There were Maoist insurgent forces actually blowing up schools in the area at the time I was there in 2009. I was shown around the school by the principal, a tall guy with really thick glasses, and he explained that a couple of years earlier a group of government paramilitary forces had moved into 2 of the school’s 15 classrooms.

This school already had a problem keeping kids in schools, particularly girls. So the government gave them 200 scholarships to get girls back in school. But the parents were unwilling to let the girls go back because of the armed men living there.

That’s when it really hit home. Here was one arm of the government doing its best to get kids into school, while the actions of another arm of the same government were making that impossible.

What’s next for this work?

At last count, there are 87 countries that have signed the Safe Schools Declaration. We would really like to see other countries, particularly those in the midst of conflict, sign the declaration so children there can go to school in safety.