The International Monetary Fund (IMF) monitors the economic health of 189 member countries, and regularly publishes an analysis of each country’s economy, called an Article IV report, highlighting key economic risks. The IMF has long recognized systemic corruption as a serious economic threat, and in 1997 it committed to promoting good governance and tackling corruption as an essential part of its mission. New data analysis of Article IV reports over the past 15 years sheds light on how well the IMF has lived up to this promise.

Two scholars from Central European University, David Mihalyi, who also works at Natural Resource Governance Institute, and Akos Mate, created a dataset of over 2,500 Article IV consultation and program review documents published between 2004 and 2017. They used the dataset as a rough tool to gauge the priorities and thinking of IMF country teams on topics such as resource governance and public finance. Human Rights Watch, based on data provided by the authors, analyzed the trove of documents to get a sense of how frequently they mention the word “corruption.” The results were mixed.

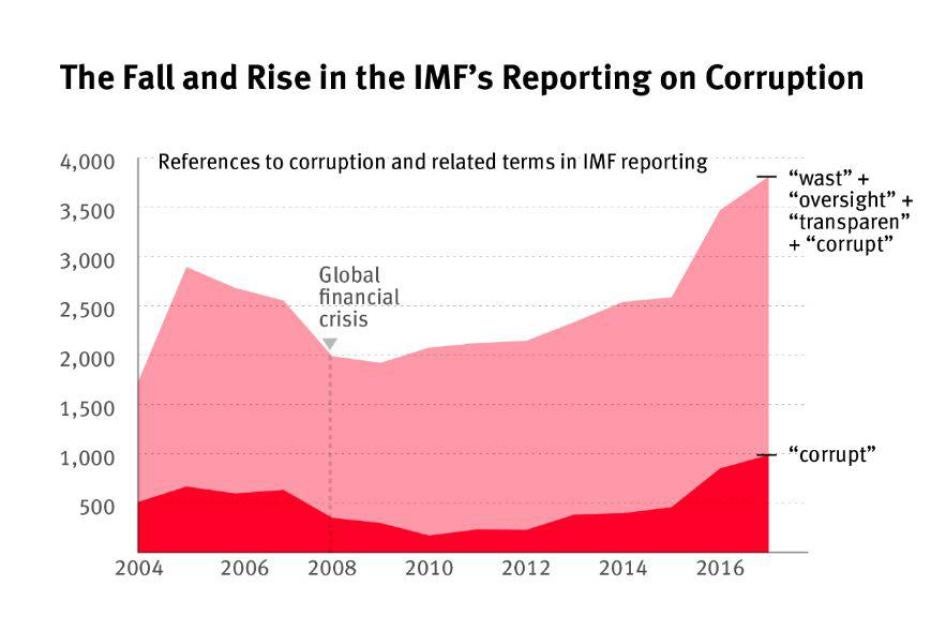

The number of times the Fund mentioned corruption plummeted after the Great Recession hit the global economy in 2008. It continued to pay relatively less attention to corruption for the next eight years. But in 2016 that changed. The number of times the Fund explicitly addressed corruption in its reporting nearly doubled to 850 references compared to 458 the previous year. In 2016, the IMF began an internal review on how it addresses corruption. That review led to a new framework for improving the Fund’s fight against corruption, launched in 2018.

Because the IMF frequently uses euphemisms to address corruption, the documents were also analyzed for references to “waste,” “lack of oversight,” and “transparency.” As the graphic indicates, the findings were similar, if somewhat less dramatic.

As the Fund acknowledged, its treatment of corruption is highly uneven across countries. Human Rights Watch’s analysis highlight reviews of Fund programs in specific countries have intensive discussions of corruption absent from most country reports. For example, in the seven years following Afghanistan’s request for financial assistance in 2011, reports on the country mentioned “corruption” 323 times, a ten-fold increase over the previous seven years. But this also appears to be changing: In a hopeful sign, the number of countries about which the Fund reports mentioned corruption more than three times rose from a low of ten in 2009 to 46 in 2017.

These are only words and not evidence of more substantive anti-corruption policies. Nevertheless, naming the problem and transparency are keys to fighting corruption. The sharp increase in calling out corruption is a hopeful sign that the IMF is taking its renewed commitment to fighting corruption seriously. But in the years ahead, the real test will be how it integrates anti-corruption measures into its loans and other assistance programs.