Some of these children and their families resorted to buying Bangladeshi identity documents as the only way to secure a secondary school education and their future. Now, the authorities are targeting and expelling those students. Government policy is leaving Rohingya children without options. Human Rights Watch researcher Bill Van Esveld spoke to some former students who had their right to education ripped away by a government edict. Here are just two of their stories:

“Rahim R.”

Holding back tears, Rahim tried to compose himself with deep breaths so he could talk about what losing his education meant to him.

“My heart is being broken. … [T]he authorities knew I was Rohingya. I don’t know what happened this year.”

Barely 18, Rahim wore his school uniform to be interviewed – a white-collared shirt and navy trousers, slightly rolled up at the ankle. The outfit must remind him of the painful day in January – a few days into what would have been his final year of school – when the head of his school received a letter from the government demanding all Rohingya children be expelled.

The note was read aloud in every class, Rahim said, and all the Rohingya children were forced to stand up in front of their classmates.

“I felt so very shy at that moment. I went and hid and cried.”

Rahim was born in Bangladesh in 2001 – 10 years after his parents fled Myanmar. When he was 4, he started going to lessons in the camp where he lived with his parents and siblings. But after completing class 5, the last year of primary education, he discovered there were no more classes offered in the camp. What’s more, education in the camps is unaccredited. This means kids who get through the lower classes receive a certificate that doesn’t give them access to any secondary education.

This is what happened to Rahim. When he left the camp’s education system, he realized none of the Bangladeshi schools outside the camp saw his five years of education as valid. He was stuck.

“As long as I had a dream to become a doctor and serve my own community, I had to look for other [school] options.”

Even though he was just 9 at the time, Rahim persisted. He managed to repeat class 5 in a Bangladeshi school, which allowed him to take an official Primary School Certificate exam. He scored an A+ and was admitted to a junior high school. After another three years he got another A+ in his Junior School Certificate at the end of class 8. After that he had to change schools yet again so he could study science.

“There were only five students out of the whole [class] who got an A+, so the teacher [of a different school] agreed to admit me into class 9.”

After years of struggle, repeating classes, and constant pressure to perform, Rahim’s goal finally felt within grasp. But on January 28, his hopes were dashed.

Now he teaches his younger brothers and sisters, as well as 20 or so other children in the camp in a makeshift school. He still holds on to his dream of being a doctor, because, he says, his grandfather died because he didn’t get the medical care he needed.

“I was very little then. … My mother taught me that it’s your duty to serve your nation.”

“Yusef Y.”

Yusef’s hands are calloused from labor and darkened by the sun. They don’t match his delicate features and heart-shaped face.

“They are very hard,” he said, looking at his palms. “I’m always working.” The roughness comes from the brickfields where Yusef works, initially so he could afford school, but now because he is no longer allowed to go to classes.

Yusef’s family fled to Bangladesh, where he was born, in 1991. He had studied Burmese, English, and math – the only subjects available – in his camp’s “learning center” for four years. Then, in 2007, the Bangladeshi government enforced a new curriculum in the camps – an English translation of the Bangladesh school curriculum, which it had previously banned for Rohingya kids.

The government’s flip-flopping on what is allowed and required of the camp schools has led to many children dropping out, either from frustration at being forced to repeat classes because of the new curriculum or financial need. Yusef’s family couldn’t afford for him to repeat four years of school so he had to drop out for two years.

“I started working in a local brickfield beside my camp. I still work there. I got some money and I got admitted to a Bangladeshi school.”

When he was 9-years-old, after he passed the entrance exam, Yusef paid his own admission fee to the school using the money he had saved. When he wasn’t working, he had studied independently during the two years since dropping out of the camp school. After getting in to the school, he walked there and back every day so he could get his education.

“Other students were asking me why [I was walking]. I said I was exercising. But this wasn’t true,” Yusef said, choking back tears. “I didn’t have any money [for a ride].”

Yusef did well in all his exams and was promoted through the school system. But in January, the government note about Rohingya arrived at his school, and he was expelled.

Until then, Yusef had wanted to focus his studies on humanities so he could help his parents’ native Myanmar, the country he has never known.

“Although I have never been able to go to Myanmar or even see it, we are Myanmar nationals,” he said. “I thought I would become a leader in my community.”

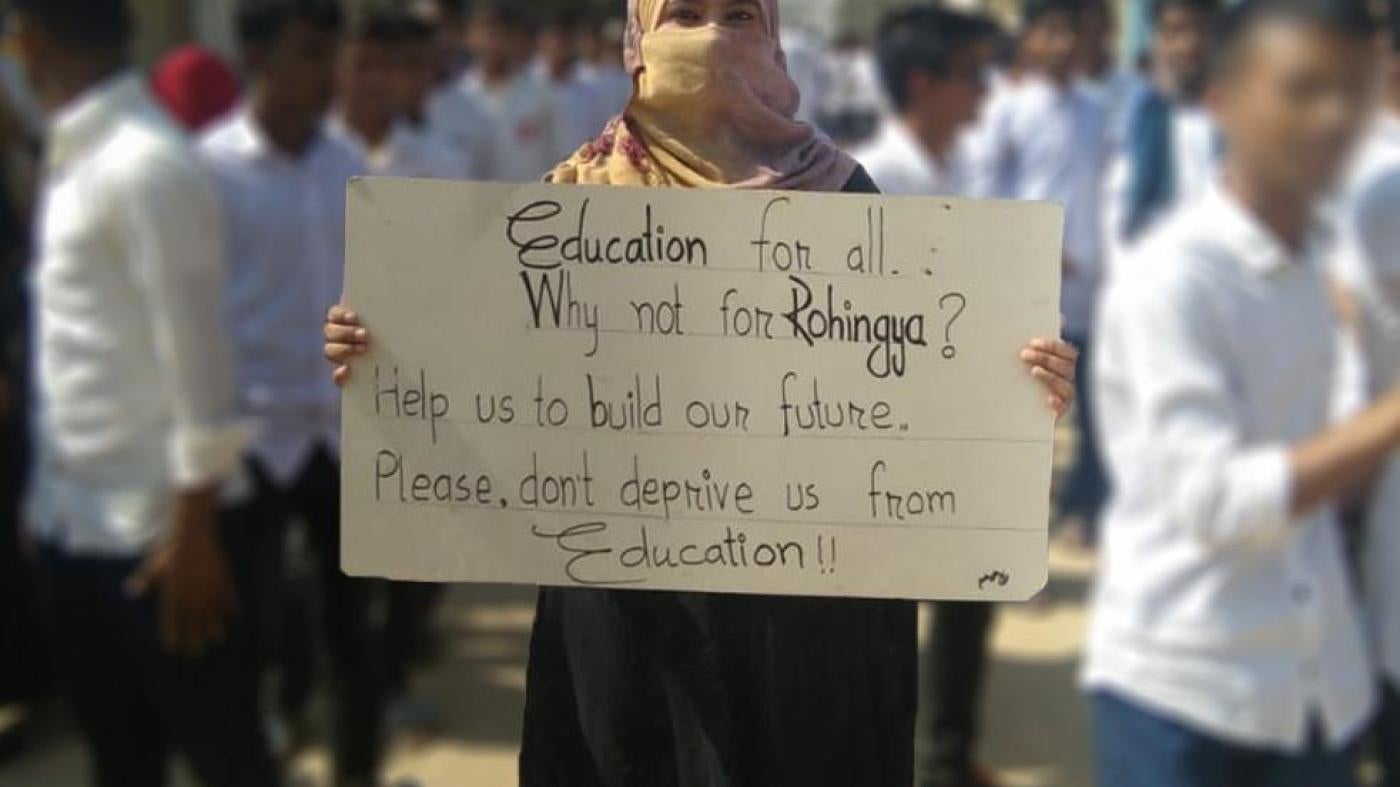

Even now, Yusef takes that idea seriously. When he learned that other Rohingya children had been expelled, he formed part of a demonstration in front of the local United Nations refugee agency office, asking for a meeting so education could be brought back to the camps.

“I thought, fine, I was expelled but now all the Rohingya were kicked out of school.”

Many of the schools Human Rights Watch visited in Bangladesh were rundown and overcrowded, so there is a very real need to improve the situation for all children in the country. But by restricting the education Rohingya kids are allowed to obtain in the camps, and at the same time forbidding them from going to Bangladeshi schools, the government is denying them their right to education and denying them a future.

Now Yusef is back in the brickfields, and also working as a wage laborer for farmers and at fisheries. Whenever he can, he reads books in Bangla on his phone to continue his studies on his own. He also worries about his siblings, four brothers and three sisters, six of whom are illiterate.

“We are always thankful to the Bangladesh government. They gave us shelter [but] we just want our education.”