(Kinshasa) – Government repression in the Democratic Republic of Congo six months before scheduled elections has heightened concerns of widespread political violence. On June 23, 2018, the Catholic Church’s Lay Coordination Committee (CLC) said in a letter to the African Union that it was preparing new protests and described a “total crisis of confidence” in the electoral process and the risks of “a certain and generalized chaos.”

Concerned governments and regional bodies should increase pressure on President Joseph Kabila and other senior officials to take urgent steps to enable free and fair elections before year’s end. Over the past three years, Congo’s ruling People’s Party for Reconstruction and Democracy and government security forces have used repression, violence, and corruption to extend their hold on power. Kabila remains in office beyond the end of his constitutionally mandated two-term limit in December 2016.

“There is still considerable uncertainty whether President Kabila will step down in accordance with the constitution and permit a credible vote that would mark Congo’s first democratic transition since independence,” said Ida Sawyer, Central Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “Kabila’s failure to do so would heighten the risk of large-scale violence and instability, with potentially devastating consequences across the region.”

Elections are now scheduled for December 23, 2018. However, Kabila has yet to declare publicly that he will step down, and the authorities could cite a host of technical, financial, and logistical constraints to call for further delays. Repression against the political opposition and human rights and pro-democracy activists has continued unabated, Human Rights Watch said.

Large-scale violence has also continued in many parts of the country, leaving close to 4.5 million people displaced, more than in any other country in Africa. Much of the violence has links to the political crisis and some appears to be part of a deliberate government strategy of chaos to justify election delays, according to well-placed security and intelligence sources.

During nationwide protests led by Catholic Church lay leaders on December 31, 2017, and on January 21 and February 25, 2018, security forces fired live bullets and teargas into Catholic church grounds to disrupt peaceful services and protest marches following Sunday Mass. Security forces killed at least 18 people, including the prominent pro-democracy activist Rossy Mukendi, and wounded or arrested dozens of others. The security forces fired teargas into three maternity wards in the capital, Kinshasa, where demonstrators had fled, threatening the lives of newborn babies.

Prior to the February 25 protests, ruling party officials recruited and paid several hundred youth to infiltrate churches, arrest priests when they attempted to march after the services, and beat those who resisted. The youth were also instructed to provoke violence and disorder to prevent the marches from going forward and to “justify” a brutal response from the security forces. Ruling party youth league members have been trained and mobilized to carry out similar violent disruptions during upcoming protests, five members told Human Rights Watch.

“For the moment, we’re on standby,” one said. “We’re waiting for the Catholics to plan the next protest, and then we’ll organize our counter-demonstrations. This time, it will be terrible.”

On April 25, security forces brutally repressed a protest led by the citizens’ movement Struggle for Change (Lutte pour le Changement, LUCHA) in Beni, in eastern Congo, arresting 42 people and injuring four others. On May 1, security forces arrested 27 activists during a LUCHA protest in Goma. On June 10, a leading LUCHA activist, Luc Nkulula, died in a suspicious fire at his home in Goma.

Meanwhile, ruling party officials have carried out increasingly brazen campaigning for Kabila to remain in power – in disregard of the constitution and the Catholic Church-mediated New Year’s Eve agreement which clearly prevent him from running again. Banners and billboards have gone up across the country with messages such as: “Joseph Kabila, President of the DRC: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow.” A video clip distributed on social media delivers a similar message, as have ruling party officials during media interviews and what appear to be campaign rallies for the president.

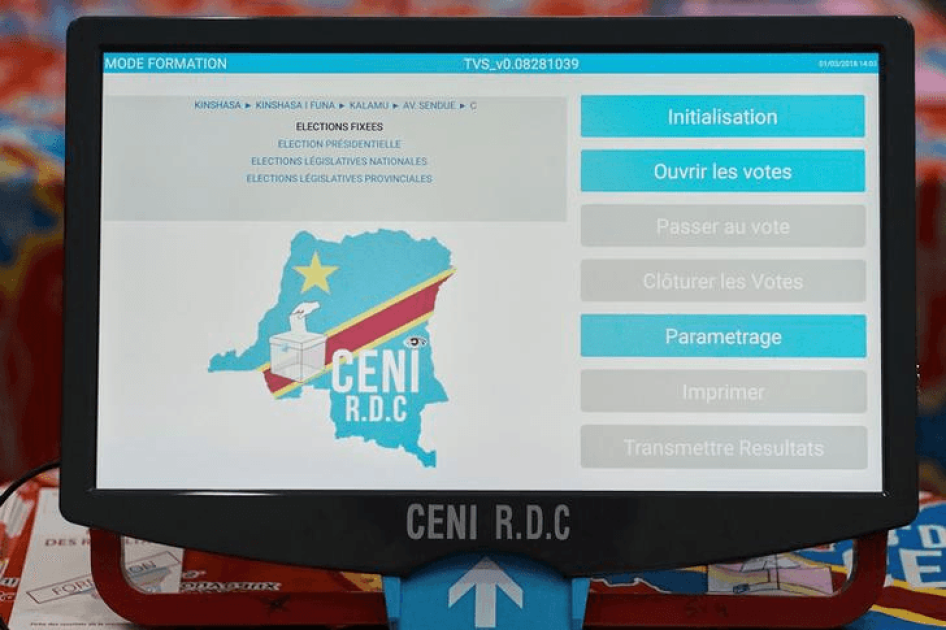

Confidence in the electoral process has been further damaged by the insistence of the national electoral commission (CENI) on using electronic voting machines, which have never been tested during an election in Congo and which political opposition and civil society leaders see as a tool to facilitate fraud. The numerous irregularities highlighted in the audit of the voter roll by the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie (OIF), including 16.6% of voters who registered without fingerprints, have raised further concerns. This is compounded by the perceived lack of independence of the CENI, the Constitutional Court, and the judicial system more broadly, and the lack of transparency regarding the financing of the electoral process.

These concerns were highlighted in a joint statement from 177 Congolese human rights groups and citizens’ movements on June 4. Rights groups and United Nations experts also fear that draft legislation on the agenda in the ongoing extraordinary session of parliament would place severe new restrictions on the ability of Congolese and international nongovernmental organizations to operate freely and independently in Congo.

The political crisis is on the agenda of the ongoing African Union summit. High-level visits to Congo are planned in the coming weeks, including a joint visit by UN Secretary-General António Guterres and AU Chairperson Moussa Faki.

“Upcoming high-level visits and regional meetings create important opportunities to deliver strong and coordinated messages to President Kabila and other top Congolese officials,” Sawyer said. “Visiting leaders should be clear that further delays in holding the December 23 elections, a Kabila re-election run, or further efforts to block opposition candidates will carry severe consequences.”

Background

Congolese government security forces have killed nearly 300 people during largely peaceful political protests since 2015, including by recruiting former fighters from the abusive M23 armed group to take part in the crackdown. Security services have arrested hundreds of political opposition supporters and pro-democracy and human rights activists. Many were mistreated and held in illegal detention by the intelligence services for weeks or months, without charge or access to their families or lawyers, while others were put on trial on trumped-up charges.

A Catholic Church-mediated power-sharing agreement signed on December 31, 2016, and known as the “New Year’s Eve agreement,” called for elections to be held by the end of 2017 and for “confidence building measures” to ease tensions and open political space. Congo’s ruling coalition has largely flouted these commitments.

In November 2017, the national electoral commission, CENI, published an electoral calendar setting December 23, 2018, as the date for presidential, legislative, and provincial elections. This followed a visit to Congo by the US Ambassador to the UN Nikki Haley, who had called for Kabila to step down in accordance with the constitution and for elections to be organized by the end of 2018.

Since then, the UN Security Council, the UN secretary-general and his special envoy, the African Union chairperson, the Southern African Development Community (SADC), the European Union, and other regional and international organizations and leaders have called for this calendar to be respected and the confidence building measures carried out to ensure that elections are credible.

On June 23, the CENI president officially convoked the electorate and opened the process for submitting candidates for provincial elections. The secretary-general of Congo’s main opposition party, the Union for Democracy and Social Progress (UDPS), said on June 24 that his party’s candidate lists were ready but they would not be submitted until preconditions were met, including a rejection of the voting machines and cleaning up the voter roll.

Submitting candidates for national legislative and presidential elections is scheduled for July 25 to August 8. The media reported that Kabila will make a rare speech to parliament by July 20.

Confidence Building Measures in the New Year’s Eve Agreement

Confidence building measures listed in the New Year’s Eve agreement include releasing political prisoners, allowing political leaders living in exile to return, opening media outlets close to the opposition, and lifting the ban on peaceful political protests and meetings.

The church’s Lay Coordination Committee noted in its June 23 letter to the AU president that:

No emblematic political opponent has been liberated; no political leader in exile has been able to return to the country; social and political tensions continue to be maintained with fanciful detentions and arbitrary arrests of members of citizens movements and pro-democracy and human rights activists; restrictions on democratic space and the media have not been lifted; and the ban on political demonstrations has only been lifted in a selective manner to fool the international community.

While some political prisoners and activists have been released, many others have been arrested since the agreement was signed. Jean-Claude Muyambo and Eugène Diomi Ndongala, who were both named explicitly in the agreement, remain in detention.

Related Content

Human Rights Watch has documented the cases of 24 human rights and pro-democracy activists and political opposition leaders or supporters who were arrested as part of the government’s campaign of political repression since 2015 and who remain in detention. Many have been held for months in illegal detention by the intelligence services. Others have suffered deteriorating health in detention, including the youth activist Carbone Beni and the opposition leaders Gérard Mulumba Kongolo (“Gecoco”), Franck Diongo, and Jean-Claude Muyambo.

One exiled person named in the agreement, Roger Lumbala, was allowed to return to Congo after demonstrating his allegiance to Kabila. Three others named in the agreement remain in exile: the former Katanga governor, opposition leader, and declared presidential candidate Moise Katumbi; the pro-democracy activist and leader of the Filimbi citizens’ movement Floribert Anzuluni; and the opposition leader and former minister and rebel leader Antipas Mbusa Nyamwisi.

In 2016, Katumbi was convicted in absentia for forgery regarding a real estate deal many years earlier and sentenced to three years in prison and a US$1 million fine. One of the judges later told Human Rights Watch that the National Intelligence Agency threatened her and forced her to hand down the conviction. In July 2017, armed men shot and nearly killed another judge who refused to rule against Katumbi.

A confidential report by Congo’s conference of Catholic bishops (CENCO) on two of the “emblematic cases” listed in the agreement, which was leaked to the media and seen by Human Rights Watch, found that the trials against Katumbi and Muyambo were politically motivated, plagued by irregularities, and “nothing but farces.” The report called for the immediate release of Muyambo and for the withdrawal of the arrest warrant and dismissal of proceedings against Katumbi, and the release of Katumbi’s associates who remained in detention.

In early June 2017, the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) called on the Congolese government to take all necessary measures to ensure Katumbi’s return and his free and safe participation as a presidential candidate and to protect him against all forms of arrest or arbitrary detention. Many Congolese see Katumbi’s return as a key a test for the inclusivity and credibility of the December elections.

At least four media outlets close to the opposition remain closed, including: Radio Télévision Lubumbashi JUA (RTLJ), which is owned by Muyambo; Nyota TV and Radio Télévision Mapendo, which are owned by Katumbi, and the La Voix du Katanga radio and television station, owned by Gabriel Kyungu.

The government has denied or revoked visas for several international journalists and researchers, preventing them from continuing to work in Congo. The Congolese government issued a decree on June 14 requiring online media to seek prior government approval for advertisements, among other new regulations. The online media outlets were given 30 days to comply with these provisions. There are concerns the requirements will be used to crack down on Congo’s vibrant online media.

Human Rights Minister Marie Ange Mushobekwa announced during the UN Human Rights Council’s interactive dialogue on Congo on March 20 that the suspension of public political demonstrations had been lifted. However, this does not reflect a real change in policy, as numerous peaceful protests have been repressed since her announcement, including in Kinshasa, Lubumbashi, Sankuru, Goma, Nyiragongo, Bunia, Beni, and Kisangani. In a positive development, opposition leaders Felix Tshisekedi on April 24 and Katumbi via video conference on June 9 were able to hold rallies without security incidents.

Crackdown During Catholic Church-Led Protests

The Lay Coordination Committee had called for protests on December 31, January 21, and February 25 to press for full implementation of the Catholic Church-mediated New Year’s Eve agreement. The protests were backed by Congo’s main opposition parties and civil society groups.

Human Rights Watch previously documented that during the December 31 protests Congolese security forces surrounded churches and fired within parish grounds, killing at least eight people and injuring dozens, including at least 27 who suffered gunshot wounds.

Security forces used similar tactics during the next protest, on January 21, erecting roadblocks and heavily deploying throughout Kinshasa and other cities. Despite the intimidation, thousands of worshipers and other Congolese joined with priests in marches following Sunday Mass. Many protesters were dressed in white, sang hymns as they marched, and carried visible religious symbols – such as crosses, bibles, rosaries, and palms.

Security forces responded by firing teargas and live ammunition to disperse the peaceful protesters, killing at least eight people in Kinshasa and wounding many others, including at least 23 who suffered gunshot wounds. According to the Catholic Church, security forces dispersed protesters with teargas and live ammunition in at least 75 parishes in Kinshasa.

A priest in Kinshasa told Human Rights Watch what happened when the march began:

We came to a barrier with unarmed police officers, who told us to return to the parish. While we were negotiating with them, another group of well-armed police officers came from behind. We all got down on our knees to show the peaceful nature of our protest. These police also told us to go back to the parish. Then suddenly, they started firing teargas and live bullets into the air. This provoked a total panic among the crowd; some worshipers lay down on the ground, while others started to run in every direction.

Human Rights Watch also documented that security forces dressed in civilian clothes fired on peaceful demonstrators. A video filmed in Kinshasa’s Kintambo neighborhood on January 21 shows at least four men in civilian clothes with assault rifles patrolling the street. One of them fires, apparently at a group of protesters in the distance. Two former and one current security force officers told Human Rights Watch that they recognized at least one of the people in the video as an officer from the Republican Guard presidential security detail.

A currency trader said that he witnessed soldiers in civilian clothes chase down protesters on the avenue in Kintambo where the video was filmed:

While the youth were demonstrating against the killing of Deshade [Thérèse] Kapangala [a peaceful protester shot by the security forces earlier that day], soldiers in civilian clothes arrived in a jeep and started firing at them. Then the soldiers got out of the jeep and chased the protesters down the street, shooting in the air. Everyone panicked.

In other neighborhoods on January 21, armed members of the security forces were seen wearing black and white skeleton masks, apparently to intimidate protesters. Some wore regular civilian clothes with the masks, while others were dressed in all black.

A witness said that armed men in civilian clothes were mixed in among the demonstrators:

After Mass on January 21, we started the march, and after walking about 50 meters, the police started dispersing us with teargas. Young men in civilian clothes who were in the crowd with us then took out their weapons and started arresting protesters. We quickly realized that we had been infiltrated.

Following widespread condemnation of the repression on January 21, Congolese authorities appeared to shift tactics before the February 25 protests. During a parade on February 24, Kinshasa’s provincial police commissioner, Gen. Sylvano Kasongo, instructed the police not to fire live bullets at protesters during the marches planned the next day, setting a target of “zero deaths.” Two police officers confirmed to Human Rights Watch that they had received explicit orders not to kill protesters.

This time, ruling party youth were deployed to intimidate parishioners and priests, provoke violence, and block the protests. And security forces killed at least two people, in Kinshasa and Mbandaka. The Catholic Church reported that at least 32 people were injured, including 13 with gunshot wounds, and another 76 were arrested in Kinshasa.

In addition to the protests in Kinshasa, worshipers and others attempted to protest on January 21 and February 25 in Beni, Bukavu, Goma, Lubumbashi, Mbandaka, Mbuji-Mayi, and Kisangani. Across the country, security forces used unnecessary and excessive force to disperse peaceful protesters.

As during previous protests, the Congolese government ordered telecommunication companies to block text messages and internet access across Congo on January 21 and February 25 in an apparent attempt to prevent information about the protests from spreading. Service was restored on January 23 and in the evening of February 25.

Accounts of Killings by Security Forces during Protests

Police shot 24-year-old Thérèse Kapangala, who was studying to be a nun, at Saint-François parish in Kinshasa on January 21. Her brother told Human Rights Watch:

That morning, my sister had gone to church to pray. After the service, she followed the Lay Committee’s call to protest peacefully. They began marching behind the parish priest and acolytes. Just when they were leaving the parish grounds, police fired teargas to disperse them, and the churchgoers ran back inside the church. Then an anti-riot police vehicle stopped just outside the parish, and a police officer stood up on the vehicle and started shooting live bullets. This is when my sister, who was standing near a door of the church, was hit by a bullet that went through her arm and pierced her heart. We tried to revive her, but she died in a vehicle on the way to the hospital.

The uncle of an 18-year-old student said that his nephew was killed in Kinshasa on January 21 by a well-known police officer in his neighborhood, wearing civilian clothes:

Once [my nephew] thought things were calm after the demonstrations, he went outside to get sugar for tea. Two motorcycles with police officers in plain clothes drove onto the avenue, they saw my nephew outside, and one of them fired at him, point-blank. The bullet hit him in the jaw and he died immediately. One of the police officers then said into his phone, “We got one!” [My nephew] was in the final year of his studies, and he did not deserve what happened to him.

On February 25, police in Kinshasa shot Rossy Mukendi, 35, a well-known pro-democracy activist from the Collectif 2016 citizens’ movement and a teaching assistant at the National Pedagogical University (UPN). He was closing the parish gate at Saint Benoit parish as police dispersed people trying to march and churchgoers returned inside the parish grounds. The policeman who fired at Mukendi was in a jeep, sitting next to a well-known senior police officer.

Some witnesses said that the officer pointed at Mukendi before his colleague shot him. Mukendi was actively involved in mobilizing participation in all three CLC marches. Just after Mukendi was shot, police tried to take him away, delaying his arrival at a hospital where he could have received treatment that might have saved his life.

Police held Mukendi’s body until May 18, despite a growing public outcry. When his family was finally able to bury him, police fired teargas at Mukendi’s friends as they carried his coffin from the church to the cemetery.

The father of Eric Bolokoloko, 25, said that police shot his son when he was returning from the march in Mbandaka, on February 25:

My son had gone to Mass, and the march after Mass had gone well. But as my son was returning home, a river police officer shot at him. The bullet pierced his forehead and came out through the back of his skull. He died on the spot.

Accounts of People Injured During the Protests

In Kinshasa on January 21, police fired teargas into a maternity ward in Ngaliema commune when they were pursuing protesters and bystanders, some of whom had fled into the maternity ward to seek shelter. Three teargas canisters fell right next to the babies’ room, putting their lives in danger, said witnesses and employees at the ward.

On February 25, the police fired teargas into two other maternity homes, in Ngaliema and Lemba communes, where protesters had fled, again endangering the lives of several newborn babies and their mothers.

A midwife nurse in one of the maternity wards hit on February 25 said:

After Mass, a riot police vehicle followed by several policemen on foot tried to disperse the protesters. They fired teargas in all directions. After the first teargas canister went into the maternity ward, we yelled out at the police, telling them that there is a maternity ward here, but they did not listen to us. Then the second and the third [teargas canisters] fell into the ward. The first two exploded, and there was gas in the whole yard. The smell of the gas endangered the lives of 15 newborn babies, including one who was just born minutes earlier and was out in the courtyard when the teargas hit. We quickly brought that baby into the room with the other babies and covered the windows to try to prevent the gas from coming in. The mothers put margarine and water on the babies’ faces and on their own faces for protection. I think the babies are okay today, but we don’t know what the long-term effects might be.

A nurse from the other maternity ward hit by teargas on February 25 said that a baby who inhaled teargas had to be transferred to the hospital for specialized care, after his skin turned a bluish purple from the cyanosis caused by the teargas.

A doctor described treating a baby who had inhaled teargas during the protests on February 25 in Kinshasa:

A couple in my neighborhood came to me with their baby who had inhaled teargas during the protest. I was able to save the baby’s life. The teargas canister had fallen right in their compound when the police fired teargas in all directions.

In Goma, a 24-year-old Catholic student and activist from the Social Movement for Renewal (MSR) opposition political party said he was hit by a teargas projectile during the January 21 demonstration:

Nothing had been organized in my parish on January 21, so I decided to pray at St. Joseph Cathedral and join the peaceful march following the service there. After the Mass, we brought out our banners and started marching for about 50 meters. Then the police showed up and dispersed us with teargas. We all went back into the parish, and the police formed a belt outside the parish to prevent us from going out again. Then they began firing teargas into the parish grounds. Some of the young people responded by throwing stones at the police. It was then that the police intensified the teargas. I was at the door of the church when a projectile hit my nose. I fell to the ground, and I was in a lot of pain. My nose bled profusely. My friends put a wet coat on my nose and poured water on my head to calm the flow of blood. The Red Cross arrived later and treated me.

In Bukavu, as police fired teargas to disperse protesters on January 21, one police officer used a bayonet and badly injured a protester, fracturing his arm. In Kisangani, police fired teargas and live bullets to disperse protesters outside several churches. Five protesters had serious injuries, including two who were beaten by police officers, two others who were hit by splinters from teargas cannisters, and one person who was hit by a bullet in the thigh.

Arrests During Protests

According to the UN Joint Human Rights Office, at least 121 people, including four children, were arbitrarily arrested on January 21 and more than 100 people were arrested on February 25. According to the Catholic Church, 210 people were arrested on January 21 – 147 in Kinshasa, 14 in Kisangani, 9 in Lubumbashi, 2 in Mbuji-Mayi, and 38 in Bukavu and Goma. The church reported 76 arrests across the country on February 25.

Many of those arrested were pro-democracy activists and church officials. In Goma on January 21, Human Rights Watch documented the arrests of 11 protesters, including 7 activists from the LUCHA DRC and LUCHA DRC Africa citizens movements, outside the St. Joseph Cathedral. They were first detained for five days in an underground cell, where they were beaten, denied visits, and barely given anything to eat. They were later transferred to Goma’s central prison and charged with violating church grounds, sequestering priests, and malicious destruction of the Cathedral. They were acquitted on March 19 and released the next day.

In Kisangani, police arrested three priests on February 25 after violently dispersing the worshipers walking with them toward Kisangani’s main cathedral. They were all released later that night. In Bukavu, police arrested an activist from the Telema citizens’ movement on February 25 as they dispersed protesters. He was released later that day.

Security forces had previously arrested dozens of people prior to and during the December 31 protests. Many of them remain in detention, including Filimbi’s national coordinator, Carbone Beni, and Filimbi activists Grâce Tshunza, Mino Bompomi, and Cédric Kalonji, who were all arrested on December 30. Another Filimbi activist, Palmer Kabeya, was abducted in Kinshasa on December 23. He was detained in a cell at the military intelligence services, without access to his family or a lawyer, until April 3, 2018, then transferred to the 3Z jail of the National Intelligence Agency. On June 7, the five Filimbi activists were transferred to the prosecutor’s office and later Kinshasa’s central prison. They are accused of “insulting the Head of State” and “threatening state security,” among other charges, their lawyer said. The activists were denied provisional release, and their trial is due to begin on July 29.

The CLC leaders who called for the three protests have also faced increasing pressure. During a news conference on February 22, Congo’s justice minister confirmed that arrest warrants had been issued for five of the eight CLC leaders. Some members have received threats, forcing them all to live in hiding and making it increasingly difficult for them to continue their work.

Mobilization of Ruling Party Youth to Disrupt Protests

In the lead-up to the February 25 protests, officials from the ruling People’s Party for Reconstruction and Democracy (PPRD) recruited hundreds of the party’s youth and others to assault peaceful protesters in Kinshasa. Human Rights Watch interviewed five current members of the ruling party’s youth league and a former leader.

The recruits included members of the Young Leaders group within the PPRD, which was created and supported by the former PPRD secretary-general and the current vice prime minister and interior minister, Henri Mova Sakanyi. The PPRD youth were joined on February 25 by youth associated with Vita Club – one of Kinshasa’s main soccer clubs, whose president is Gen. Gabriel Amisi, commander of the first zone of defense of the Congolese army, based in Kinshasa. He has long been alleged to be involved in serious abuses.

On February 24, at about 3 p.m., over 100 youth arrived on public, government-owned Transco buses at Notre Dame cathedral, Kinshasa’s main parish, where Cardinal Laurent Monsengwo, the archbishop of Kinshasa and a vocal critic of the government, celebrates Mass. Wearing red berets – a trademark of the Young Leaders group – they occupied the cathedral grounds, led by the group’s president, Papy Pungu Lwamba, who told the media they had come “to take possession” of the cathedral to “defend the homeland” and that they planned to spend the night at the cathedral. The priests cancelled the evening Mass due to the disruption.

The same day, a video began circulating, showing the Young Leaders’ national coordinator, Popol Badjegate, instructing recruits in Lingala, the main language spoken in Kinshasa. He said they should arrive at churches at 5 a.m., and then arrest any priest who tried to start marching after services. “We say this to you now because you are the political soldiers of the Rais [Kabila],” he said. “You were trained for three years. This Sunday, we will go to battle. Our objective is to protect the homeland.” Human Rights Watch spoke to two Young Leaders members who were at the meeting and confirmed the authenticity of the video.

Early the next day, the youth deployed to parishes across Kinshasa. “When the march was about to start, we were told to arrest the priests and then take them to the police,” a Young Leaders member told Human Rights Watch. “If they resisted, we had the authorization to beat them.”

Many priests cancelled the planned protests when they saw youth wearing red berets – with some claiming to be the “soldiers of Kabila” – inside and surrounding their churches during and before the Sunday services. Others decided only to hold a small procession within the parish grounds. Priests told Human Rights Watch that they were concerned the protests could turn violent.

“We were alerted by the church’s protocol service and other worshipers that infiltrators had come to attend Mass, armed with knives, and that intelligence agents were deployed all around the parish,” one priest said. “We then decided to cancel the march and instead hold a procession within the church grounds.”

Lwamba was effectively rewarded for his actions. On April 20, he was nominated president of the PPRD’s youth league. He was previously one of the league’s vice-presidents and replaced the former president, Patrick Nkanga, who had publicly distanced himself from the Young Leaders’ deployment on February 24 and 25.

Young Leaders said they have participated in training sessions since 2016, with the following individuals leading sessions and involved in mobilization and recruitment: Mova, Lwamba, Badjegate, the Young Leaders’ vice-president, Yannick Tshisola, a senior PPRD official Claude Mashala, and Zoe Kabila, the president’s brother and an elected member of parliament from the PPRD. During the training sessions, the youth were taught the ideology of the PPRD and how to infiltrate and gather intelligence about the opposition and pro-democracy groups, provoke violence during protests and neutralize the opposition leaders, and quickly evacuate bodies of those killed by security forces during protests, according to youth league members.

Two current Young Leaders members told Human Rights Watch that Zoe Kabila was present at a mobilization and training meeting that they attended in the days leading up to the February 25 protest, and that he gave a “motivational speech” to the recruits.

Over the past year and a half, the Young Leaders have conducted “exchange visits” with the Imbonerakure, the ruling party youth league in neighboring Burundi known for brutal killings, rapes, torture, and beatings. In April 2017, a group of Imbonerakure visited Kinshasa and met with members of the PPRD youth league. In August 2017, a group of PPRD youth league members, including Young Leaders, travelled to Bujumbura, Burundi’s capital, for a meeting with members of the Imbonerakure. Many observers feared that these exchanges would lead the PPRD youth league to start using the abusive tactics of the Imbonerakure.

Young Leaders members told Human Rights Watch that their training has continued since February 25, 2018, and that they are awaiting instructions for the next protests. During a meeting in Kinshasa on April 21, the permanent secretary of the PPRD, Ramazani Shadari, told new PPRD recruits, according to video footage verified by Human Rights Watch, “If they insult you, then you should respond by insulting them.”

Human Rights Watch has documented that ruling party officials and security force officers previously recruited youth league members to disrupt protests and provoke violence during earlier demonstrations, including in September 2015, September 2016, and December 2016.

Additional information, August 8, 2018: In an official letter to Human Rights Watch on July 18, 2018, Zoé Kabila through his lawyer in Brussels responded to allegations made to Human Rights Watch regarding his participation in the mobilization of ruling party youth. The full response from Zoé Kabila is available here: https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/supporting_resources/right_reply_zoekabila_to_hrw.pdf.